Читать книгу Modern Japanese Prints - Statler - Oliver Statler - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE

From the rime they first laid eyes on them, foreigners have been captivated by Japanese prints. Toward the end of the last century, the ukiyoe of the Edo period (1615-1867) cut a wide swath through Europe and America, and the excitement they engendered then still lingers. A growing number of foreigners are finding something of the same excitement today as they seek out the great prints of contemporary Japanese artists.

This book is concerned only with sosaku hanga, the creative prints which are one-man works. It cannot cover all the artists, for there are more than three hundred working in the media of sosaku hanga today. My aim has been a representative and diversified selection, but such a choice is necessarily controversial and I shall be delighted if controversy ensues. My hope is that the reader will seek out the prints of the movement—for they are now to be found all over the world—and decide for himself.

With the exception of the great pioneer, Yamamoto, and the great realizer, Onchi, whose death midway in the preparation of this book saddened the whole effort, attention is confined to artists who are actively working today. I have tried' to tell something of their lives and their thinking, of the way they work and the background of their prints, but I have not attempted a critical analysis of their art, because I feel that the prints speak for themselves.

There is a woeful lack of material on this subject in English. James A. Michener has provided a brilliant introduction in the last chapter of The Floating World, telling the story in terms of but two artists, Koshiro Onchi and Un'ichi Hiratsuka. The only other comprehensive reference in English is Dr. Shizuya Fujikake's invaluable handbook, Japanese Wood-block Prints, published in the Japan Travel Bureau's Tourist Library. Because of the limited material available, I have tried to avoid reproducing prints already shown in either of these two books, but in some cases an important print demanded inclusion.

I cannot list here all those who helped me, but I must acknowledge the helpful suggestions made by Ellen Psaty and the kind assistance of Professors Joseph Roggendorf, S. J., and Edward G. Seidensticker, who translated the poems of Koshiro Onchi which appear in the appendix. And I am especially grateful to Ansei Uchima, who saw me through my language difficulties. The fact that Uchima is also an artist made everything easier, and one of the pleasantest rewards of this work has been entirely unexpected: Uchima himself has turned to the medium of prints with every indication of brilliant success. He does not belong in this book, because he is an American, but his prints show again what happy results can come from cross-fertilization in art.

This book would be incomplete without mention of William Hartnett. I, and many more like me, first saw modern Japanese prints through the exhibitions he arranged in the early days of the Occupation. Hartnett's taste and enthusiasm played an enormous part in giving these artists the encouragement and recognition they needed, and for his good work we may all be grateful.

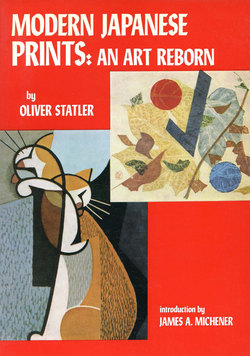

The frontispiece is the gift of Toyohisa Adachi, one of the notable publishers of prints in Japan today. In producing this woodblock reproduction of Koshiro Onchi's Impression of a Violinist, Adachi drew on the finest skills available, and the result is faithful even in spirit. His gift is not only a warm act of friendship but a generous tribute to the work of Onchi and the sosaku artists.

Both general and technical information concerning the prints reproduced in the book will be found in an appendix. Also given in an appendix is brief data on the woods used by contemporary Japanese artsts to make the blocks for their prints.

Paper is obviously of vital importance in print-making, but the subject is an extremely technical one. Prints are invariably made on handmade papers (to the Japanese these are "Japanese" papers; machine-made papers are "Western" papers). The fibers of most of the handmade papers of Japan come from the inner bark of one of three plants. Gampi (Wickstroemia shikpfyana, Franchetet Savatier) papers are tough, lustrous, and long-lived, but non-absorbent and therefore little used for prints. Mitsumata (Edgeworthia papyrifera, Siebold et Zuccarini) is of the same family as gampi but more refined; mixed with pulp it is used to make modern torinoko, a paper which is very popular among the sosaku hanga artists (the frontispiece is made on a torinoko paper). Kozo (Broussonetia kazinoki, Siebold) is of the same family as mulberry; its fibers are sinewy and tough, with an appealing roughness; kozo papers are strong, elastic, and porous, and are widely used in print-making. Japanese writers have ascribed noble dignity to gampi papers, gentle elegance to mitsumata papers, and tough masculinity to kozo papers, but the print artist is less concerned with these poetic attributes than he is with practical considerations such as absorbency, strength, and color reaction.

Japanese names are given throughout in the foreign manner, that is, with the given name first and the family name last. For those who are interested, in the index the long vowels of Japanese words have been indicated and, in the case of names, Japanese characters added.

And finally, though this is by no means a technical treatise, a few Japanese words relating to the technique of the woodblock reoccur, and definition here may simplify things. They are:

Baren: the pad, faced with a bamboo sheath, with which the printer rubs the back of his paper as it lies on the printing block in order to fix the impression on the paper.

Kento: the marks on the corners of a printing block by which the printer positions his paper on the block to insure registry.

Sumi: the black ink which the Japanese use for painting, for writing with a brush, and, of course, for making prints.

OLIVER STATLER

Tokyo, February 15, 1956