Читать книгу Modern Japanese Prints - Statler - Oliver Statler - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

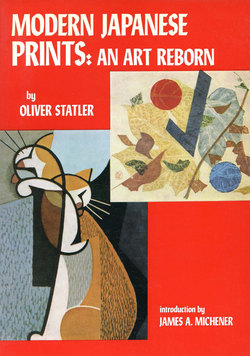

AN ART

REBORN

"ART MUST MOVE IN CYCLES, THERE MUST BE CONTINUOUS INTER-change. The new must become old and the. The old must come back...."

With these words James A. Michener closes The Floating World, the trenchant and illuminating book in which he pictures the life and death of the traditional art of ukiyoe, the great woodblock prints of Japan. As we look back at the history of ukiyoe, its inglorious death is as evident as its magnificent life, and yet, because art does move in cycles, Michener was able to end on a note of optimism as he described the rebirth of prints today.

For Japanese prints have been reborn. Revived is not the proper word. You will look in vain for modern prints of beautiful women like Utamaro's, of actors like Sharaku's, or of landscapes like Hiroshige's. What we are experiencing is a renascence, not a restoration. The new prints are as much a part of today as old ukiyoe prints were of their day. And it does not take a historian to grasp the difference between the Japan of today—industrial, centralized, inextricably caught up in international currents—and the Japan of ukiyoe's day—agricultural, feudal, sealed from the outside world, an introverted recluse.

This is no place to dwell on the death of ukiyoe. The era of the Emperor Meiji (1868-1912), ushered in by Perry's knock on the door, saw Japan look about, take stock, and then plunge headlong into the modern world. In the upheaval there were many casualties; ukiyoe, already weakened by the factors Michener describes so well, was only one of these.

In their race to catch up with the Western world the Japanese made few reservations. In art, as in industry, they set out to learn new ways, and hundreds of artists turned from brushing ink on paper to daubing oil on canvas. Then some of them made an astonishing discovery. They found that their European idols, the impressionists and post impressionists, had been obviously excited and just as obviously influenced by Japanese ukiyoe. It was a curious experience, to go halfway around the world to find the honored oil painters of the West in turn honoring the prints of Japan, things the Japanese themselves had never taken very seriously. Japanese artists who went to Europe made a further discovery: European artists were making their own prints—carving their own blocks, doing their own printing. It was cause for reflection.

Reflect they did, these new foreign-style artists of Japan. They reconsidered the past glories of ukiyoe and discerned the greatness there. They weighed the Japanese prints of their own day and saw the humiliating fall from grace. Especially, they pondered the new concept that an artist should make his own prints.

This was an idea which violated the whole tradition of ukiyoe. Ukiyoe were the astounding result of collaboration unheard of in other fields of art anywhere in the world, a collaboration between a man who provided the picture or design, a man who cut that design onto the blocks, a man who printed from those blocks, and a man who, we may suspect, was in many cases the dominant personality: the publisher. When the new print artists of Japan turned to one-man creations their self-designed, self-carved, self-printed, and mostly self-published prints were such a departure from Japanese tradition that a new name was coined for them. The artists called them "creative prints."

Of course, certain woodcut prints are still being made in Japan by the time-honored artist-artisan-publisher teams. Some of these "modern ukiyoe" have a great deal of charm and they are backed by centuries of accumulated skill. They are a respectable reflection of a great art, but they differ significantly from traditional ukiyoe in at least one way. In the palmy days of ukiyoe the print was created in cooperative team effort. The artist's contributions were rough sketches, often uncolored, and ideally, supervision of the artisans at every vital stage of the carving and printing. For example, the original brush stroke of the ukiyoe artist was very different from the final print line: by common agreement the artisan did not reproduce the artist's line but carved a line based on the heart of the artist's brush stroke. "Modern ukiyoe" prints, however, are originally done as full-scale color paintings, by say Hasui Kawase or Shinsui Ito, which the artisans then transform into woodprints as faithfully as possible. Thus the charge that woodprints are merely a reproductive art, which is unfair when applied to the great traditional ukiyoe, can be leveled against those "modern ukiyoe" prints of today with a good deal of justification.

However, despite the fact that the ukiyoe tradition has been kept alive, it is impossible to trace any direct connection from the dying ukiyoe to the new creative prints. The connection is by rebound from the West, and the creative prints are the result of interaction between Japanese and Western influences, which continues to this day. To borrow the euphemistic phrase which the Japanese apply to their Occupation babies, modern Japanese creative prints are children of mixed blood.

On the Japanese side of this inheritance is the great technique of the woodblock print. Without this, these creative prints could never have happened. Only in Japan does any significant number of artists feel impelled to concentrate on this medium. Regardless of an artist's personal reaction to ukiyoe, the woodcut as a medium is deep in his national heritage.

From the West comes their artistic content, a legacy already influenced by ukiyoe. No one is asked to believe that Japanese art does not in some degree influence a Japanese artist, but artistically most of the new prints are as Western as shoes.

The Japanese artist even dallied a while with the European style of woodcuts made from blocks cut across the grain, but speedily reverted to blocks cut along the grain in traditional ukiyoe style. As can be seen from the accompanying sketch, blocks cut across the grain are restricted in size to the rectangle which can be cut within the circumference of the trunk, while a block cut along the grain can be as wide as the full diameter of the trunk and, within reason, as long as the artist wishes. Furthermore, the use of the long grain of the wood as an element of the design was an inherent feature of the medium and too much in the Japanese tradition to be cast aside. Now only a handful of Japanese artists ever carve a block cut across the grain, a process they call wood engraving: Un'ichi Hiratsuka and Jun'ichiro Sekino, for example, sometimes use this technique to make book illustrations, as Thomas Bewick did in England. Today the whole problem seems a little dated, for the advent of plywood veneer has made possible larger (and cheaper, and easier to work) blocks than ever before, and most of the creative-print artists use plywood for their blocks.

From its beginnings in the first decade of this century the new creative-print movement rapidly gained momentum, and though the rest of the Japanese art world chose to ignore it, it began to attract serious attention abroad. In the 1930's a number of full-scale exhibitions went to Europe and America, but of course World War II put an end to that.

After the war the artists began the battle to re-establish themselves. In one way the fight was easier, for now the country was flooded with foreigners, and foreigners have always been the most enthusiastic champions of Japanese prints. Anyone who wonders why this is true must realize that traditional ukiyoe was a "popular art." It was mass-produced to sell. To sell it had to catch the public fancy—and it did, blazoning the celebrated figures and foibles of its day. It was cheap and democratic. Such a "popular art" always carries a stigma in its own country. Foreigners, untroubled by background associations, see it fresh and on its own merits, but it is only natural that many art-conscious Japanese, intensely proud of their nation's painting and sculpture, should regard ukiyoe as something on the outer fringe of artistic respectability.

Since "ukiyoe" and "prints" are popularly synonymous in Japan, the whole medium falls under the same shadow. And if the towering achievements of traditional ukiyoe are regarded with scepticism, so much the worse for a group of modern mavericks who perversely choose the same medium. Here is the ironic twist, for creative prints are not a "popular art" at all. Behind these new prints there is an entirely different urge—the conscious desire of an artist to create a work of art. The creative-print artist uses the technique of the woodprint not as a means to achieve multiple copies of a picture but as a means to create a picture.

This is the answer to the inevitable question: why do these modern artists feel it necessary to carve their own blocks when artisans might have more skill with a chisel, and to print their own pictures when other artisans might do a cleaner job?

The creative-print artist really creates his picture as he works with his wood, his chisels, and his colors. The method varies with each artist and often from print to print. He may work from a fairly complete sketch, a rough sketch, or no sketch at all, but the real act of design starts when he goes to work with block and knife, guided by his inner conception, and with full appreciation for the personality of his materials and his tools. This is a process of creation which he feels he cannot delegate.

There is another difference between traditional ukiyoe and modern creative prints which should be pointed out: the creative prints are not exclusively woodcuts. The Japanese have a generic term, hanga, which is defined as a picture made with a block. By Japanese usage this definition includes etchings, lithographs, mimeographs, and similar forms as well as woodblock prints. Furthermore, in making what we commonly call woodblock prints the new artists do not restrict themselves to wood, but also use a variety of materials such as paper, string, and leaves. The creative-print artists prefer to think of their field as hanga, broadly defined, and many of them roam freely among the different techniques.

One of the most encouraging things about the new prints is that each artist is unique. Traditional ukiyoe artists usually developed in schools, the style of whose members became additionally similar because they used the same artisans. Today each of the creative artists follows his own path. The result is so lively and vigorous that it is sometimes a little difficult to keep up with developments.

In telling the story of creative prints one cannot avoid emphasizing the difficulties which these artists have had in their own country. Still there have been important exceptions, and one great expert like Shizuya Fujikake, who was the first to write critically of creative prints, goes far to balance the scale. It is worth remembering that there were a few, like this brilliant and beloved dean of ukiyoe scholars, who saw the strong beauty of creative prints before foreigners pointed it out. Dr. Fujikake has never wavered. "Creative hanga is postwar Japan's best contribution to the art of the world," he says today. "Generally speaking, Japan's postwar art is not good; the shining exception is creative hanga. Creative hanga is showing the world the good art of contemporary Japan in the same way that traditional ukiyoe showed the good art of an older age."