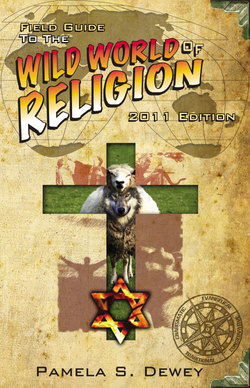

Читать книгу Field Guide to the Wild World of Religion: 2011 Edition - Pamela J.D. Dewey - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The quiet before the storm

ОглавлениеIf you reached adulthood in the 1950s, and got married and had a family of your own, chances are very good that you and your family would be found attending the church denomination of your childhood when Sunday morning came around. Whether that church was St. Catherine’s Roman Catholic Church, Central United Methodist, or the First Baptist Church of Anytown, it was probably a pretty tame, predictable place. The differences of doctrine among the Protestant Churches in your town would have been distinct enough to the dedicated members of each of the denominations. But they would probably not be as clear to outsiders as the differences in superficial matters such as the style of music or sermon presentation in each of the denominational churches.

It wasn’t unheard of for people to “change churches” in the 1950s. But seldom would some family leave one congregation and go to another in the same town over a matter of doctrinal considerations. The typical reason for a move would be “in-house politics” at their old congregation—a dispute over who was in charge, or who would make decisions about expenditures. In fact, it wouldn’t be all that uncommon for there to be a “First Baptist Church” and a “Second Baptist Church” in the same small town. But it would not be because the First Baptist congregation outgrew its building and started a sister congregation. It would be because a disgruntled faction of members and deacons and elders from First Baptist stomped out and started their own new church so that they could do things their own way.

This is not to say that, in the 1950s and on into the 1960s, there were not a few “unusual” religious groups working around the fringes of American society to make converts. The “Moonies” (followers of the Reverend Sun Myung Moon) were one such group that occasionally made the news, standing on street corners and handing out flowers. The “Children of God” (followers of “Mo” Berg, who used sexual favors by women members to lure new converts) were even more notorious for a time. There was even a flurry of activity to combat the recruiting tactics of such groups. Some frightened parents whose teens had run off to join a commune of such people hired “deprogrammers” to kidnap their own children and try to talk some sense into them.

But these groups were all squarely on the outside of the mainstream of society, and easily recognized as strange and unconventional. There were also a few slightly more respectable alternatives to the mainline Protestant Churches that were fairly small in the 1950s, but beginning to grow in numbers and influence. These would include the Mormons, the Seventh Day Adventists, and the Jehovah’s Witnesses (JWs). In most towns their presence was barely noticed, even if they had a small permanent building in which they met. They did engage in evangelistic efforts, but most people were more bemused than troubled when approached, for instance, by JWs going door to door to pass out their Watchtower Magazine.