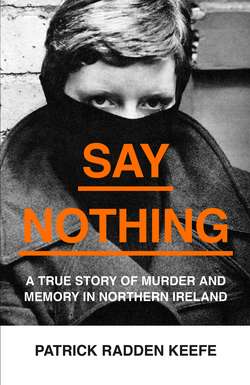

Читать книгу Say Nothing: A True Story Of Murder and Memory In Northern Ireland - Patrick Keefe Radden - Страница 12

Albert’s Daughters

ОглавлениеWhen Dolours Price was a little girl, her favoured saints were martyrs. Dolours had one very Catholic aunt on her father’s side who would say, ‘For God and Ireland.’ For the rest of the family, Ireland came first. Growing up in West Belfast in the 1950s, she dutifully went to church every day. But she noticed that her parents didn’t. One day, when she was about fourteen, she announced, ‘I’m not going back to Mass.’

‘You have to go,’ her mother, Chrissie, said.

‘I don’t, and I’m not going,’ Dolours said.

‘You have to go,’ Chrissie repeated.

‘Look,’ Dolours said. ‘I’ll go out the door, I’ll stand at the corner for half an hour and say to you, “I’ve been to Mass.” But I won’t have been to Mass.’

She was headstrong, even as a child, so that was the end of that. The Prices lived in a small, semi-detached council house on a tidy, sloping street in Andersonstown called Slievegallion Drive. Her father, Albert, was an upholsterer; he made the chairs that occupied the cramped front room. But where another clan might adorn the mantelpiece with happy photos from family holidays, the Prices displayed, with great pride, snapshots taken in prisons. Albert and Chrissie Price shared a fierce commitment to the cause of Irish republicanism: the belief that for hundreds of years the British had been an occupying force on the island of Ireland – and that the Irish had a duty to expel them by any means necessary.

When Dolours was little, she would sit on Albert’s lap and he would tell her stories about joining the Irish Republican Army when he was still a boy, in the 1930s, and about how he had gone off to England as a teenager to carry out a bombing raid. With cardboard in his shoes because he couldn’t afford to patch the soles, he had dared to challenge the mighty British Empire.

A small man with wire-framed glasses and fingertips stained yellow by tobacco, Albert told violent tales about the fabled valour of long-dead patriots. Dolours had two other siblings, Damian and Clare, but she was closest to her younger sister, Marian. Before bedtime, their father liked to regale them with the story of the time he escaped from a jail in the city of Derry, along with twenty other prisoners, after digging a tunnel that led right out of the facility. One inmate played the bagpipes to cover the sound of the escape.

In confiding tones, Albert would lecture Dolours and her siblings about the safest method for mixing improvised explosives, with a wooden bowl and wooden utensils – never metal! – because ‘a single spark and you were gone’. He liked to reminisce about beloved comrades whom the British had hanged, and Dolours grew up thinking that this was the most natural thing in the world: that every child had parents who had friends who’d been hanged. Her father’s stories were so rousing that she shivered sometimes when she listened to them, her whole body tingling with goose bumps.

Everyone in the family, more or less, had been to prison. Chrissie’s mother, Granny Dolan, had been a member of the IRA Women’s Council, the Cumann na mBan, and had once served three months in Armagh jail for attempting to relieve a police officer from the Royal Ulster Constabulary of his service weapon. Chrissie had also served in the Cumann and done a stretch in Armagh, along with three of her sisters, after they were arrested for wearing a ‘banned emblem’: little paper flowers of orange, white and green, known as Easter lilies.

In the Price family – as in Northern Ireland in general – people had a tendency to talk about calamities from the bygone past as though they had happened just last week. As a consequence, it could be difficult to pinpoint where the story of the ancient quarrel between Britain and Ireland first began. Really, it was hard to imagine Ireland before what the Prices referred to simply as ‘the cause’. It almost didn’t matter where you started the story: it was always there. It pre-dated the distinction between Protestant and Catholic; it was older than the Protestant Church. You could go back nearly a thousand years, in fact, to the Norman raiders of the twelfth century, who crossed the Irish Sea on ships, in search of new lands to conquer. Or to Henry VIII and the Tudor rulers of the sixteenth century, who asserted England’s total subjugation of Ireland. Or to the Protestant emigrants from Scotland and the North of England who filtered into Ireland over the course of the seventeenth century and established a plantation system in which the Gaelic-speaking natives became tenants and vassals on land that had previously been their own.

But the chapter in this saga that loomed largest in the house on Slievegallion Drive was the Easter Rising of 1916, in which a clutch of Irish revolutionaries seized the post office in Dublin and declared the establishment of a free and independent Irish Republic. Dolours grew up hearing legends about the dashing heroes of the rising, and about the sensitive poet who was one of the leaders of the rebellion, Patrick Pearse. ‘In every generation, the Irish people have asserted their right to national freedom,’ Pearse declared on the post office steps.

Pearse was an inveterate romantic who was deeply attracted to the ideal of blood sacrifice. Even as a child, he had fantasies of pledging his life for something, and he came to believe that bloodshed was a ‘cleansing’ thing. Pearse praised the Christlike deaths of previous Irish martyrs and wrote, a few years before the rising, that ‘the old heart of the earth needed to be warmed with the red wine of the battlefield’.

He got his wish. After a brief moment of glory, the rebellion was mercilessly quashed by British authorities in Dublin, and Pearse was court-martialled and executed by a firing squad, along with fourteen of his comrades. After the Irish War of Independence led to the partition of Ireland, in 1921, the island was split in two: in the South, twenty-six counties achieved a measure of independence as the Irish Free State, while in the North, a remaining six counties continued to be ruled by Great Britain. Like other staunch republicans, the Price family did not refer to the place where they happened to reside as ‘Northern Ireland’. Instead it was ‘the North of Ireland’. In the fraught local vernacular, even proper nouns could be political.

A cult of martyrdom can be a dangerous thing, and in Northern Ireland, rituals of commemoration were strictly regulated, under the Flags and Emblems Act. The fear of Irish nationalism was so pronounced that you could go to jail in the North just for displaying the tricolour flag of the Republic. As a girl, Dolours donned her best white frock for Easter Sunday, a basket full of eggs under her arm and, pinned to her chest, an Easter lily, to commemorate the botched rebellion. It was an intoxicating ritual for a child, like joining a league of secret outlaws. She learned to cover the lily with her hand when she saw a policeman coming.

She was under no illusions, however, about the personal toll that devotion to the cause could exact. Albert Price never met his first child, an older daughter who died in infancy while he was behind bars. Dolours had an aunt, Bridie, one of Chrissie’s sisters, who had taken part in the struggle in her youth. On one occasion in 1938, Bridie had been helping to move a cache of explosives when it suddenly detonated. The blast shredded both of Bridie’s hands to the wrist, disfiguring her face and blinding her permanently. She was twenty-seven when it happened.

Against the projections of her doctors, Aunt Bridie survived. But because she was so incapacitated, she would require care for the rest of her life. With no hands or eyes, she couldn’t change her clothes or blow her nose or do much else for herself without assistance. Bridie often stayed for stretches in the house on Slievegallion Drive. If the Price family felt pity for her, it was secondary to a sense of admiration for her willingness to offer up everything for an ideal. Bridie came home from the hospital to a tiny house with an outside toilet, no social worker, no pension – just a life of blindness. Yet she never expressed any regret for having made such a sacrifice in the name of a united Ireland.

When Dolours and Marian were little, Chrissie would send them upstairs with instructions to ‘talk to your Aunt Bridie’. The woman would be stationed in a bedroom, alone in the gloom. Dolours liked to tiptoe as she ascended the stairs, but Bridie’s hearing was extra sharp, so she always heard you coming. She was a chain-smoker, and from the age of eight or nine, Dolours was given the job of lighting Bridie’s cigarettes, gently inserting them between her lips. Dolours hated this responsibility. She found it revolting. She would stare at her aunt, scrutinising her face more closely than you might with someone who could see you doing it, taking in the full horror of what had happened to her. Dolours was a loquacious kid, with a child’s manner of blurting out whatever came into her head. Sometimes she would ask Bridie, ‘Do you not wish you’d just died?’

Taking her aunt’s stumpy wrists into her own small hands, Dolours stroked the waxen skin. They reminded her, she liked to say, of ‘a pussycat’s paws’. Bridie wore dark glasses, and Dolours once watched a tear descend from behind the glass and creep down her withered cheek. And Dolours wondered: How can you cry if you have no eyes?

On the cold, clear morning of 1 January 1969, a band of student protesters assembled outside City Hall in Donegall Square, in the centre of Belfast. Their plan was to walk from Belfast to the walled city of Derry, some seventy miles away, a march that would take them several days. They were protesting systemic discrimination against Catholics in Northern Ireland. Partition had created a perverse situation in which two religious communities, which for centuries had felt a degree of tension, each came to feel like an embattled minority: Protestants, who formed a majority of the population in Northern Ireland but a minority on the island as a whole, feared being subsumed by Catholic Ireland; Catholics, who represented a majority on the island but a minority in Northern Ireland, felt that they were discriminated against in the six counties.

Northern Ireland was home to a million Protestants and half a million Catholics, and it was true that the Catholics faced extraordinary discrimination: often excluded from good jobs and housing, they were also denied the kind of political power that might enable them to better their conditions. Northern Ireland had its own devolved political system, based at Stormont, on the outskirts of Belfast. For half a century, no Catholic had ever held executive office.

Excluded from the shipbuilding industry and other attractive professions, Catholics often simply left, emigrating to England or America or Australia, in search of work they couldn’t find at home. The Catholic birth rate in Northern Ireland was approximately double the Protestant birth rate – yet during the three decades prior to the march on Derry, the Catholic population had remained virtually static, because so many people had no choice but to leave.

Perceiving, in Northern Ireland, a caste system akin to the racial discrimination in the United States, the young marchers had chosen to model themselves explicitly on the American civil rights movement. They had studied the 1965 march by Dr Martin Luther King and other civil rights leaders from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. As they trudged out of Belfast, bundled in duffel coats, daisy-chained arm in arm, they held placards that read, CIVIL RIGHTS MARCH, and sang ‘We Shall Overcome’.

Dolours and Marian Price

One of the marchers was Dolours Price, who had joined the protest along with her sister Marian. At eighteen, Dolours was younger than most of the other marchers, many of whom were at university. She had grown up to be an arrestingly beautiful young woman, with dark-red hair, flashing blue-green eyes and pale lashes. Marian was a few years younger, but the sisters were inseparable. Around Andersonstown, everyone knew them as ‘Albert’s daughters’. They were so close, and so often together, that they could seem like twins. They called each other ‘Dotes’ and ‘Mar’, and had grown up sharing not just a bedroom but a bed. Dolours had a big, assertive personality and a sly irreverence, and the sisters plodded through the march absorbed in a stream of lively chatter, their angular Belfast accents bevelled, slightly, by their education at St Dominic’s, a rigorous Catholic high school for girls in West Belfast; their repartee punctuated by peals of laughter.

Dolours would later describe her own childhood as an ‘indoctrination’. But she was always fiercely independent-minded, and she was never much good at keeping her convictions to herself. As a teenager, she had started to question some of the dogma upon which she had been raised. It was the 1960s, and the nuns at St Dominic’s could do only so much to keep the cultural tides that were roiling the world at bay. Dolours liked rock ’n’ roll. Like a lot of young people in Belfast, she was also inspired by Che Guevara, the photogenic Argentine revolutionary who fought alongside Fidel Castro. That Che was shot dead by the Bolivian military (his hands severed, like Aunt Bridie’s, as proof of death) could only help to situate him in her menagerie of revolutionary heroes.

But even as tensions sharpened between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland, Dolours had come to believe that the armed struggle her parents championed might be an outdated solution, a relic of the past. Albert Price was an emphatic conversationalist, a lively talker who would wrap his arm around your shoulder, tending his ever-present cigarette with the other hand, and regale you with history, anecdote and charm until he had brought you around to his way of seeing things. But Dolours was an unabashed debater. ‘Hey, look at the IRA,’ she would say to her father. ‘You tried that and you lost!’

It was true that the history of the IRA was in some ways a history of failure: just as Patrick Pearse had said, every generation staged a revolt of one sort or another, but by the late 1960s, the IRA was largely dormant. Old men would still get together for weekend training camps south of the border in the Republic, doing target practice with antique guns left over from earlier campaigns. But nobody took them very seriously as a fighting force. The island was still divided. Conditions had not improved for Catholics. ‘You failed,’ Dolours told her father, adding, ‘There is another way.’

Dolours had started attending meetings of a new political group, People’s Democracy, in a hall on the campus of Queen’s University. Like Che Guevara, and many of her fellow marchers, Dolours subscribed to some version of socialism. The whole sectarian schism between Protestants and Catholics was a poisonous distraction, she had come to believe: working-class Protestants may have enjoyed some advantages, but they, too, often struggled with unemployment. The Protestants who lived in grotty houses along Belfast’s Shankill Road didn’t have indoor toilets either. If only they could be made to see that life would be better in a united – and socialist – Ireland, the discord that had dogged the two communities for centuries might finally dissipate.

One of the leaders of the march was a raffish, articulate young socialist from Derry named Eamonn McCann, whom Dolours met and became fast friends with on the walk. McCann urged his fellow protesters not to demonise the Protestant working people. ‘They are not our enemies in any sense,’ McCann insisted. ‘They are not exploiters dressed in thirty-guinea suits. They are the dupes of the system, the victims of the landed and industrialist unionists. They are the men in overalls.’ These people are actually on our side, McCann was saying. They just don’t know it yet.

Ireland is a small island, less than two hundred miles across at its widest point. You can drive from one coast to the other in an afternoon. But from the moment the marchers departed Donegall Square, they had been harried by counterprotesters: Protestant ‘unionists’, who were ardent in their loyalty to the British crown. Their leader was a stout, jug-eared forty-four-year-old man named Ronald Bunting, a former high school maths teacher who had been an officer in the British Army and was known by his followers as the Major. Though he had once held more progressive views, Bunting fell under the sway of the ardently anti-Catholic minister Ian Paisley after Paisley tended to Bunting’s dying mother. Bunting was an Orangeman, a member of the Protestant fraternal organisation that had long defined itself in opposition to the Catholic population. He and his supporters jostled and jeered the marchers, attempting to snatch their protest banners, while raising a flag of their own – the Union Jack. At one point, a journalist asked Bunting whether it might not have been better just to leave the marchers be and ignore them.

‘You can’t ignore the devil, brother,’ Bunting said.

Bunting may have been a bigot, but some of his anxieties were widely shared. ‘The basic fear of Protestants in Northern Ireland is that they will be outbred by Roman Catholics,’ Terence O’Neill, the prime minister of Britain’s devolved government in Northern Ireland, said that year. Nor did it seem entirely clear, in the event that Protestants were eventually outnumbered in such a fashion, that London would come to their rescue. Many people on the English ‘mainland’ seemed only faintly aware of this restive province off the coast of Scotland; others would be happy to let Northern Ireland go. After all, Britain had been shedding colonies for decades. One English journalist writing at the time described the unionists in Northern Ireland as ‘a society more British than the British about whom the British care not at all’. To ‘loyalists’ – as especially zealous unionists were known – this created a tendency to see oneself as the ultimate defender of a national identity that was in danger of extinction. In the words of Rudyard Kipling, in his 1912 poem ‘Ulster’, ‘We know, when all is said,/We perish if we yield.’

But Major Bunting may have had a more personal reason to feel threatened by this march. Among the scruffy demonstrators with their hippie songs and righteous banners was his own son. A student at Queen’s with heavy sideburns, Ronnie Bunting had drifted into radical politics during the summer of 1968. He was hardly the only Protestant among the marchers. Indeed, there had been a long tradition of Protestants who believed in Irish independence; one of the heroes of Irish republicanism, Wolfe Tone, who led a violent rebellion against British rule in 1798, was a Protestant. But Ronnie was surely the only member of the march whose father was the architect of a nettlesome counterprotest, leading his own band of loyalist marchers in a campaign of harassment and bellowing anti-Catholic invective through a megaphone. ‘My father’s down there making a fool of himself,’ Ronnie grumbled, shamefaced, to his friends. But this oedipal dynamic seemed only to sharpen the resolve of both father and son.

Like the Price sisters, Ronnie Bunting had joined People’s Democracy. At one meeting, he suggested that it might be better if they did not proceed with the march to Derry, because he thought that ‘something bad’ was likely to happen. The police had cracked down violently on several earlier protests. Northern Ireland was not exactly a bastion of free expression. Due to fears of a Catholic uprising, a draconian law, the Special Powers Act, which dated to the era of partition, had created what amounted to a permanent state of emergency: the government could ban meetings and certain types of speech, and could search and arrest people without warrants and imprison them indefinitely without trial. The Royal Ulster Constabulary was overwhelmingly Protestant, and it had a part-time auxiliary, known as the B-Specials, composed of armed, often vehemently anti-Catholic unionist men. One early member, summarising how the B-Specials were recruited, said, ‘I need men, and the younger and wilder they are, the better.’

As the march progressed through the countryside, it kept running into Protestant villages that were unionist strongholds. Each time this occurred, a mob of local men would emerge, armed with sticks, to block the students’ access, and a cordon of police officers accompanying the march would force them to detour around that particular village. Some of Major Bunting’s men walked alongside the marchers, taunting them. One carried a Lambeg drum – the so-called big slapper – and its ominous thump echoed through the green hills and little villages, summoning other able-bodied counterprotesters from their homes.

If there was a violent clash, the students felt prepared for it. Indeed, some of them welcomed the idea. The Selma march had provoked a ferocious crackdown from the police, and it may have been the televised spectacle of that violent overreaction, as much as anything else, that sparked real change. There was a sense among the students that the most intractable injustice could be undone through peaceful protest: this was 1969, and it seemed that young people around the world were in the vanguard. Perhaps in Northern Ireland the battle lines could be redrawn so that it was no longer a conflict of Catholics against Protestants, or republicans against loyalists, but rather the young against the old – the forces of the future against the forces of the past.

On the fourth and final day of the march, at a crossroads ten miles outside Derry, one of the protesters shouted through a megaphone, ‘There’s a good possibility that some stones may be thrown.’ It appeared there might be trouble ahead. More young people had joined the procession over the days since it departed Belfast, and hundreds of marchers now filled the road. The man with the megaphone shouted, ‘Are you prepared to accept the possibility of being hurt?’

The marchers chorused back, ‘Yes!’

The night before, as the marchers slept on the floor of a hall in the village of Claudy, Major Bunting had assembled his followers in Derry, or Londonderry, as Bunting called it. Inside the Guildhall, a grand edifice of stone and stained glass on the banks of the River Foyle, hundreds of hopped-up loyalists gathered for what had been billed as a ‘prayer meeting’. And there, ready to greet his flock, was Ian Paisley.

A radical figure with a rabid following, Paisley was the son of a Baptist preacher. After training at a fringe evangelical college in Wales, he had established his own hard-line church. At six foot four, Paisley was a towering figure with squinty eyes and a jumble of teeth, and he would lean over the pulpit, his hair slicked back, his jowls aquiver, and declaim against the ‘monster of Romanism’. The Vatican and the Republic of Ireland were secretly in league, engineering a sinister plot to overthrow the Northern Irish state, he argued. As Catholics steadily accrued power and numbers, they would grow into ‘a tiger ready to tear her prey to pieces’.

Paisley was a Pied Piper agitator who liked to lead his followers through Catholic neighbourhoods, sparking riots wherever he went. In his basso profundo, he would expound about how Catholics were scum, how they ‘breed like rabbits and multiply like vermin’. He was a flamboyantly divisive figure, a maestro of incitement. In fact, he was so unsympathetic, so naked in his bigotry, that some republicans came to feel that on balance, he might be good for their movement. ‘Why would we kill Paisley?’ Dolours Price’s mother, Chrissie, had been known to say. ‘He’s our greatest asset.’

Though the population of Derry was predominantly Catholic, in the symbolic imagination of loyalists, the city remained a living monument to Protestant resistance. In 1689, Protestant forces loyal to William of Orange, the new king, had managed to hold the city against a siege by a Catholic army loyal to James II. In some other part of the world, an event of such faded significance might merit an informative plaque. But in Derry, the clash was commemorated every year, with marches by local Protestant organisations. Now, Paisley and Bunting suggested, the student protesters who were planning to march into Derry the following morning might as well be re-enacting the siege.

These civil rights advocates might pretend they were peaceful protesters, Paisley told his followers, but they were nothing but ‘IRA men’ in disguise. He reminded them of Londonderry’s role as a bulwark against papist encroachment. Did they stand ready to rise once again in defence of the city? There were cheers of ‘Hallelujah!’ It was Paisley’s habit to whip a crowd into a violent lather and then recede from the scene before any actual stones were thrown. But as his designated adjutant, Major Bunting instructed the mob that anyone who wished to play a ‘manly role’ should arm themselves with ‘whatever protective measures they feel to be suitable’.

In the darkness that night, in fields above the road to Derry, local men began to assemble an arsenal of stones. A local farmer, sympathetic to the cause, provided a tractor to help gather projectiles. These were not pebbles, but sizable hunks of freshly quarried rock, which were deposited in piles at strategic intervals, in preparation for an ambush.

‘We said at the outset that we would march non-violently,’ Eamonn McCann reminded Dolours and the other protesters on the final morning. ‘Today, we will see the test of that pious declaration.’ The marchers started moving again, proceeding slowly, with a growing sense of trepidation. They were massed on a narrow country lane, which was bordered on the right by a tall hedge. Up ahead was a bottleneck, where Burntollet Bridge, an old stone structure, crossed the River Faughan. Dolours and Marian and the other young protesters continued trudging towards the bridge. Then, beyond the hedges, in the fields above, where the ground rose sharply, a lone man appeared. He was wearing a white armband and swinging his arms around theatrically in an elaborate series of hand signals, like a matador summoning some unseen bull. Soon other figures emerged, sturdy young men popping up along the ridgeline, standing there in little knots, looking down at the marchers. There were hundreds of people on the road now, hemmed in by the hedges, with nowhere to run. More and more men appeared in the fields above, those white bands tied around their arms. Then the first rocks sailed into view.

To Bernadette Devlin, a friend of Dolours who was one of the organisers of the march, it looked like a ‘curtain’ of projectiles. From the lanes on each side of the road, men and boys materialised, scores of them, hurling stones, bricks, milk bottles. Some of the attackers were on the high ground above the road, others behind the hedges alongside it, others still swarming around to head the marchers off at the bridge. The people at the front of the group sprinted for the bridge, while those in the rear fell back to avoid the barrage. But Dolours and Marian were stuck in the middle of the pack.

They clambered over the hedge, but the stones kept coming. And now the men started running down and physically attacking the marchers. It looked to Dolours like a scene from some Hollywood western, when the Indians charge into the prairie. A few of the attackers wore motorcycle helmets. They descended, swinging cudgels, crowbars, lead pipes and laths. Some men had wooden planks studded with nails, and they attacked the protesters, lacerating their skin. People pulled coats over their heads for cover, stumbling, blind and confused, and grabbed one another for protection.

The ambush at Burntollet Bridge

As marchers fled into the fields, they were hurled to the ground and kicked until they lost consciousness. Someone took a spade and smacked a young girl in the head. Two newspaper photographers were beaten up and stoned. The mob seized their film and told them that if they came back, they would be killed. And there in the midst of it all was Major Bunting, the grand marshal, swinging his arms like a conductor, his coat sleeves blotted with blood. He snatched one of the banners from the protesters, and somebody set it on fire.

The marchers did not resist. They had agreed in advance to honour their pledge of nonviolence. Dolours Price found herself surrounded by young people with gashes on their faces and blood running into their eyes. She splashed into the river, the icy water sloshing around her. In the distance, marchers were being pushed off the bridge and into the river. As Dolours struggled in the water, she locked eyes with one attacker, a man with a club, and for the rest of her life she would return to that moment, the way his eyes were glazed with hate. She looked into those eyes and saw nothing.

Finally, an officer from the Royal Ulster Constabulary waded into the river to break up the fracas. Dolours grabbed his coat and wouldn’t let go. But even as this sturdy cop helped usher her to safety, a terrifying realisation was taking hold. There were dozens of RUC officers there that day, but most of them had done little to intervene. It would later be alleged that the reason the attackers wore white armbands was so that their friends in the police could distinguish them from the protesters. In fact, many of Major Bunting’s men, the very men doing the beating, were members of the police auxiliary, the B-Specials.

Later, on the way to Altnagelvin Hospital, in Derry, Dolours cried, seized by a strange mixture of relief, frustration and disappointment. When she and Marian finally got back to Belfast and appeared, bruised and battered, on the doorstep of the little house on Slievegallion Drive, Chrissie Price listened to the story of her daughters’ ordeal. When they had finished telling it, she had one question. ‘Why did you not fight back?’