Читать книгу Say Nothing: A True Story Of Murder and Memory In Northern Ireland - Patrick Keefe Radden - Страница 14

Evacuation

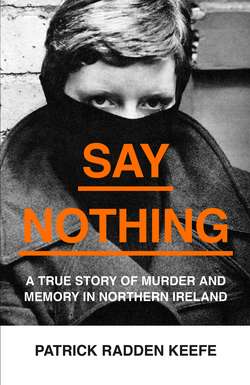

ОглавлениеJean McConville left few traces. She disappeared at a chaotic time, and the children she left behind were so young that many of them had yet to form a rich catalogue of memories. But one photograph of Jean survives, a snapshot taken in front of the family’s home in East Belfast in the mid-1960s. Jean stands alongside three of her children, while her husband, Arthur, squats in the foreground. She stares at the camera, arms folded across her chest, lips pursed into a smile, eyes squinting against the sun. One detail that several of her children would recall about Jean McConville is a nappy pin – a blue safety pin, which she wore fastened to her clothes, because one child or another was always missing a button or needing some other repair. It was her defining accessory.

She was born Jean Murray, in 1934, to Thomas and May Murray, a Protestant couple in East Belfast. Belfast was a sooty, grey city of chimneys and steeples, flanked by a flat green mountain on one side and the Belfast Lough, an inlet of the North Channel, on the other. It had linen mills and tobacco factories, a deepwater harbour where ships were built, and row upon row of identical brick workers’ houses. The Murrays lived on Avoniel Road, not far from the Harland & Wolff shipyard, where the Titanic had been built. Jean’s father worked at Harland & Wolff. Every morning when she was a child, he would join the thousands of men plodding past her house on their way to the shipyard, and every evening he would return as the procession of men plodded home in the opposite direction. When the Second World War broke out, Belfast’s linen factories produced millions of uniforms and the shipyards churned out navy vessels. Then, one night in 1941, not long before Jean’s seventh birthday, air raid sirens wailed as a formation of Luftwaffe bombers streaked across the waterfront, scattering parachute mines and incendiary bombs, and Harland & Wolff erupted into flame.

Jean McConville with Robert, Helen, Archie and her husband Arthur

Educating girls was not much of a priority in working-class Belfast in those days, so when Jean was fourteen, she left school and went in search of work. She ended up finding a job as a servant for a Catholic widow who lived on nearby Holywood Road. The widow’s name was Mary McConville, and she had a grown son – an only child named Arthur, who served in the British Army. Arthur was twelve years older than Jean and very tall. He towered over Jean, who stood barely five feet in her shoes. He came from a long line of soldiers, and he told her stories about how he had gone off to fight the Japanese in Burma during the war.

When Jean and Arthur fell in love, the fact that they came from different sides of the religious divide did not go unnoticed by their families. Sectarian tensions were less pronounced during the 1950s than they had been in the past or would become again, but even so, ‘mixed’ relationships were rare. This was true not just for reasons of tribal solidarity but because Protestants and Catholics tended to live in circumscribed worlds: they resided in different neighbourhoods, attended different schools, worked different jobs, frequented different pubs. By entering Arthur’s mother’s house as a domestic employee, Jean had crossed these lines. When she took up with Arthur, his mother resented it. (Jean’s mother may not have been delighted, either, but she accepted the marriage, though one of Jean’s uncles, a member of the Orange Order, gave her a beating for the transgression.)

The young couple eloped to England in 1952 and lived in an army barracks where Arthur was posted, but eventually they returned to Belfast and moved in with Jean’s mother, in 1957. Jean’s first child, Anne, suffered from a rare genetic condition that would leave her hospitalised for much of her life. Anne was soon followed by Robert, Arthur (who was known as Archie), Helen, Agnes, Michael (whom everyone called Mickey), Thomas (whom everyone called Tucker), Susan and, finally, the twins, Billy and Jim. Between Jean, her mother, her husband and her children, there were a dozen or so people crammed into the tiny house on Avoniel Road. Downstairs was a small front parlour and a kitchen at the back, with an outdoor toilet, an open fire for cooking, and a cold-water sink.

In 1964, Arthur retired from the army with a pension and set up a small building-repair business. But he struggled to stay employed. He found a new job in the Sirocco engineering works but eventually lost it when his employers discovered that he was Catholic. He held a job in a ropeworks for a time. Later, the children would recall this period – when the photo was taken – as a happy interlude. There were privations, to be sure, but nothing out of the ordinary for a working-class childhood in postwar Belfast. Their parents were alive. Their existence seemed stable. Their life was intact.

But during the 1960s, the mutual suspicion between Catholics and Protestants gradually intensified. When members of the local Orange Order conducted their triumphal summertime marches, they would make a point of starting right outside the McConvilles’ door. For years, Ian Paisley had been exhorting his Protestant brethren to seek out and expel Catholics who lived among them. ‘You people of the Shankill Road, what’s wrong with you?’ he would bellow. ‘Number 425 Shankill Road – do you know who lives there? Pope’s men, that’s who!’ This was retail ethnic cleansing: Paisley would reel off addresses – 56 Aden Street, 38 Crimea Street, the proprietors of the local ice cream shop. They were ‘Papishers’, agents of Rome, and they must be driven out. There was no television in the house on Avoniel Road, but as the civil rights movement got under way and Northern Ireland became embroiled in riots, Jean and Arthur would visit a neighbour’s house and watch the evening news with a growing sense of trepidation.

Michael McConville was eight when hell broke loose in 1969. Every summer in Derry, a loyalist order known as the Apprentice Boys held a march to commemorate the young Protestants who shut the city gates to bar the Catholic forces of King James in 1688. Traditionally, the marchers concluded their festivities by standing on the city’s walls and hurling pennies onto the pavements and houses of the Bogside, a Catholic ghetto, below. But this year the provocation did not go unchallenged, and violent riots broke out, engulfing Derry in what would become known as the Battle of the Bogside.

As word of the clash in Derry reached Belfast, the riot spread like an airborne virus. Gangs of Protestant youths tore through Catholic neighbourhoods, breaking windows and torching homes. Catholics fought back, throwing stones and bottles and Molotov cocktails. The RUC and the B-Specials responded to this unrest, but the brunt of their authority was felt by Catholics, who complained that the police would simply stand by while the loyalists committed crimes. Barricades sprang up around Catholic neighbourhoods as people hijacked school buses and bread vans and turned them on their sides to block off streets and create defensive fortifications. Young Catholics prised up paving stones to pile onto the barricades or to throw at police. Alarmed by this onslaught, the RUC deployed squat armoured vehicles, known as ‘Pigs’, which lumbered through the narrow streets, their gun turrets swivelling in all directions. Stones rained down on them as they passed. Petrol bombs broke open on their steel bonnets, blue flame spilling out like the contents of a cracked egg.

There were moments of anarchic poetry: a bulldozer that someone had left on a building site was liberated by a couple of kids, who sat atop the huge machine and drove it jauntily down a West Belfast street, to great whoops and cheers from their compatriots. At a certain point the boys lost control of their hulking steed and crashed into a telegraph pole – where somebody immediately lobbed a petrol bomb at the bulldozer and it burst into flames.

Loyalist gangs started moving systematically through Bombay Street, Waterville Street, Kashmir Road and other Catholic enclaves, breaking windows and tossing petrol bombs inside. Hundreds of homes were gutted and destroyed, their occupants put out onto the street. As the rioting spread, ordinary families all across Belfast boarded up their doors and windows, as if for an approaching hurricane. They would move their old furniture away from the front room so there was less to burn, in the event that any incendiary material came crashing through the window. Then they would huddle in the back kitchen, grandparents clasping their rosaries, and wait for the chaos to pass.

Nearly two thousand families fled their homes in Belfast that summer, the overwhelming majority of them Catholic. Some 350,000 people lived in Belfast. Over the ensuing years, as much as 10 per cent of the population would relocate. Sometimes a mob of a hundred people would converge on a house, forcing the inhabitants to leave. On other occasions, a note would come through the letter box, instructing the owners that they had a single hour to vacate. People crammed into cars that would shuttle them across the city to safety: it was not unusual to see a family of eight squeezed into a single car. Eventually, thousands of Catholics would queue at the railway station – refugees, waiting for passage on a southbound train to the Republic.

It was not long before the mob came for the McConvilles. A gang of local men visited Arthur and told him he had to leave. He slipped out under cover of darkness and sought refuge at his mother’s house. At first, Jean and the children stayed behind, thinking the tensions might subside. But eventually they, too, were forced to flee, packing all the belongings they could into a taxi.

The city that they traversed was transformed. Lorries whizzed to and fro with whatever furniture people could gather before moving. Men staggered through the streets under the weight of ageing sofas and wardrobes. Cars burned at intersections. Firebombed school buildings smouldered. Great plumes of smoke blotted out the sky. All the traffic lights had been shattered, so, at some junctions, young civilians stood on the street, directing traffic. Sixty buses had been commandeered by Catholics and placed along streets to form barricades, a new set of physical battle lines delineating ethnic strongholds. Everywhere there was rubble and broken glass, what one poet would memorably describe as ‘Belfast confetti’.

Yet, in the midst of this carnage, the hard-headed citizens of Belfast simply adapted and got on with their lives. In a momentary lull in the shooting, a front door would tentatively crack open and a Belfast housewife in horn-rimmed glasses would stick her head out to make sure the coast was clear. Then she would emerge, erect in her raincoat, a head scarf over her curlers, and walk primly through the war zone to the shops.

The taxi driver was so fearful of the chaos that he refused to take Jean McConville and her children any further than the Falls Road, so they were forced to lug their belongings the rest of the way on foot. They rejoined Arthur at his mother’s house, but Mary McConville had only one bedroom. She was half-blind, and because she had always disapproved of the former domestic employee who married her son, she and Jean did not get along. Besides, there were frequent gun battles in the area, and Jean and Arthur were concerned that a timber yard behind the house might be torched and the fire could spread. So the family moved again, to a Catholic school that had been converted into a temporary shelter. They slept in a classroom on the floor.

The housing authority in Belfast was building temporary accommodation for thousands of people who had suddenly become refugees in their own city, and eventually the McConvilles were offered a newly constructed chalet. But when they arrived to move in, they discovered that a family of squatters had beaten them there. Many displaced families were squatting wherever they could. Catholics moved into homes that had been abandoned by Protestants, and Protestants moved into homes vacated by Catholics. At a second chalet, the McConvilles encountered the same problem: another family was already living there and refused to leave. There were new chalets being built on Divis Street, and this time Arthur McConville insisted on staying with the workmen who were building it until the moment they finished construction, so that nobody else could get in first.

It was a simple structure, four rooms with an outside toilet. But it was the first time that they had a place they could legitimately call their own, and Jean, delighted, went straight out and bought material to make curtains. The family stayed in the chalet until February 1970, when they were offered permanent accommodation in a new housing complex known as Divis Flats, which had been under construction for several years and now loomed into view, throwing the surrounding neighbourhood into shadow.

Divis Flats was meant to be a vision of the future. Built between 1966 and 1972 as part of a ‘slum clearance’ programme, in which an ancient neighbourhood of overcrowded nineteenth-century dwellings, known as the Pound Loney, was razed, the flats consisted of a series of twelve interconnected housing blocks, containing 850 units. Inspired by Le Corbusier, the flats were conceived as a ‘city in the sky’ that would alleviate housing shortages while also providing a level of amenities that would seem downright luxurious to ordinary Belfast families like the McConvilles. Residents of Divis Flats would have a shower and an indoor toilet, along with a hot-water sink. Each level of the housing block had a wide concrete balcony running from one end to the other, onto which the flats opened. This was meant to evoke the little streets outside the terraced houses of the Pound Loney – a recreational area where children could play. Each door was painted a candy hue, and the reds and blues and yellows offered a vibrant pop of optimistic colour against Belfast’s many shades of grey.

The McConvilles moved into a four-bedroom maisonette in a section of the flats called Farset Walk. But any excitement they may have felt about their new accommodation soon dissipated, because the complex had been constructed with little consideration for how people actually live. There were no social amenities in Divis Flats, no green spaces, no landscaping. Apart from two bleak football pitches and an asphalt enclosure with a couple of swing sets, there were no playgrounds – in a complex with more than a thousand children.

When Michael McConville moved in, Divis seemed to him like a maze for rats, all corridors, stairwells and ramps. The interior walls were cheap plasterboard, so you could hear every word of the dinnertime conversation of your neighbours. And because the exterior walls were built with non-porous concrete, condensation developed, and a malignant black mould began to creep up the walls and across the ceilings of the flats. For a utopian architectural project, Divis had yielded dystopian results, becoming what one writer would later describe as a ‘slum in the sky’.

The same summer that the McConvilles were ousted from their home in East Belfast, the British Army had been sent to Northern Ireland in response to the Battle of the Bogside and the riots. Young, green-jacketed soldiers arrived on ships, thousands of them pouring into Belfast and Derry. Initially they were greeted warmly by Catholics, who welcomed the soldiers as if they were the Allied troops who’d liberated Paris. The Catholic population had been so furious at the RUC and the B-Specials, whom they regarded as sectarian authorities, that when the army (which appeared neutral by comparison) showed up, it seemed to hold the promise of greater security. In West Belfast, Catholic mothers ventured up to the army’s sandbagged posts and offered the soldiers cups of tea.

Michael’s father was more circumspect. As a retired army man himself, Arthur McConville did not like it when the soldiers came around on patrol, speaking informally to him, as if he no longer held a place in the chain of command. At one end of the Divis complex, a twenty-storey tower had been constructed, becoming the tallest building in Belfast that wasn’t a church. The first eighteen floors consisted of flats, but the British Army took over the top two for use as an observation post. As tensions mounted below, army lookouts could monitor the whole city with binoculars.

The troops had scarcely arrived before they began to lose the goodwill of the community. The young soldiers did not understand the complicated ethnic geography of Belfast. They soon came to be seen not as a neutral referee in the conflict, but rather as an occupying force – a heavily armed ally of the B-Specials and the RUC.

Catholics had started to arm themselves and to shoot at loyalist adversaries, at the police, and eventually at the army. Gun battles broke out, and a few Catholic snipers took to the rooftops by night, lying flat among the chimneys and picking off targets below. Incensed by such aggression, the army and the police would shoot back, with heavier weaponry, and the neighbourhoods echoed with the crack of M1 carbines and the harsh clatter of Sterling sub-machine guns. Thinking that it would make them harder for the snipers to spot, the B-Specials used revolvers to shoot out the street lights, which plunged the city into darkness. British troops patrolled the empty streets in their half-ton Land Rovers with their headlights off, so as not to present a target. For all the chaos, the number of people actually killed in the Troubles was initially quite low: in 1969, only nineteen people were killed, and in 1970, only twenty-nine. But in 1971, the violence accelerated, with nearly two hundred people killed. By 1972, the figure was nearly five hundred.

With a population that was almost entirely Catholic, Divis Flats became a stronghold for armed resistance. Once the McConvilles moved into the complex, they were introduced to something that local residents called ‘the chain’. When police or the army came to the front door of a particular flat in search of a weapon, someone would lean out of the back window of the flat and pass the gun to a neighbour who was leaning out of her back window in the next flat. She would pass it to a neighbour on the other side, who would pass it to someone further along, until the weapon had made its way to the far end of the building.

It was at Divis Flats that the first child to die in the Troubles lost his life. It had happened before the McConvilles moved in. One August night in 1969, two policemen were wounded by sniper fire near the complex. Prone to panic and untrained in the use of firearms in such situations, the police hosed bullets from an armoured car indiscriminately into Divis. Then, during a pause in the shooting, they heard a voice ring out from inside the building. ‘A child’s been hit!’

A nine-year-old boy, Patrick Rooney, had been sheltering with his family in a back room of their flat when a round fired by the police pierced the plasterboard walls and struck him in the head. Because intermittent volleys of gunfire continued, the police refused to allow an ambulance to cross the Falls Road. So eventually a man emerged from the flats, frantically waving a white shirt. Beside him, two other men appeared, carrying the boy, with his shattered head. They managed to get Patrick Rooney to an ambulance, but he died a short time later.

Michael McConville knew that Divis was a dangerous place. Patrick Rooney had been close to his age. At night, when gun battles broke out, Arthur bellowed, ‘Down on the floor!’ and the children would drag their mattresses to the centre of the flat and sleep there, huddled in the middle of the room. Sometimes it felt as if they spent more nights on the floor than in their beds. Lying awake, staring at the ceiling, Michael would listen to the sound of bullets ricocheting off the concrete outside. It was a mad life. But as the anarchy persisted from one month to the next, it became the only life he knew.

One July afternoon in 1970, a company of British soldiers descended into the warren of alleys around Balkan Street, off the Falls Road, looking for a hidden stash of weapons. Searching one house, they retrieved fifteen pistols and one rifle, along with a Schmeisser sub-machine gun. But as they climbed back onto their armoured vehicles and prepared to pull out of the neighbourhood, a crowd of locals confronted them and started throwing stones. In a panic, the driver of one of the Pigs reversed into the crowd, crushing a man, which further enraged the locals. As the conflict escalated, a second company of troops was sent in to relieve the first, and soldiers fired canisters of tear gas into the crowd.

Before long, three thousand soldiers had converged on the Lower Falls. They axed down doors, bursting into the narrow houses. They were officially searching for weapons, but they did so with the kind of disproportionately destructive force that would suggest an act of revenge. They disembowelled sofas and overturned beds. They peeled the linoleum off the floors, prising up floorboards and yanking out gas and water pipes. As darkness fell, a military helicopter hovered above the Falls Road and a voice announced over a loudspeaker, in a plummy Eton accent, that a curfew was being imposed: everyone must remain in their houses or face arrest. Using the tips of their rifles, soldiers unspooled great bales of concertina wire and dragged it across the streets, sealing off the Lower Falls. Soldiers patrolled the streets, wearing body armour and carrying riot shields, their faces blackened with charcoal. From the windows of the little homes, residents stared out at them with undisguised contempt.

It may have been the tear gas, as much as anything, that brought West Belfast together in virulent opposition. A cartridge would skitter across the pavement, trailing a billowing cloud, and send the adolescent rock throwers scattering. Over the course of that weekend, the army fired sixteen hundred canisters of gas into the neighbourhood, and it gusted through the narrow laneways and seeped into the cracks in draughty old homes. It crept into people’s eyes and throats, inducing panic. Young men bathed their faces with rags soaked in vinegar and went back out to throw more stones. One correspondent who reported on the siege described the gas as a kind of binding agent, a substance that could ‘weld a crowd together in common sympathy and common hatred for the men who gassed them’.

Michael McConville made the most of this turbulent boyhood. He grew up with a healthy scepticism towards authority. The British Army was no different from the police, in his view. He watched them throwing men against the wall, kicking their legs spread-eagle. He saw soldiers pull fathers and brothers out of their homes and haul them away, to be detained without trial. Arthur McConville was unemployed. But this was hardly unusual for Divis Flats, where half the residents relied entirely on welfare assistance to support their families.

When the children left the flat in Divis, Jean would tell them not to stray too far. ‘Don’t wander away,’ she would say. ‘Stay close to home.’ Technically, there was not a war going on – the authorities insisted that this was simply a civil disturbance – but it certainly felt like a war. Michael would venture out with his friends and his siblings into an alien, unpredictable landscape. Even in the worst years of the Troubles, some children seemed to have no fear. After the shooting stopped and the fires died down, kids would scuttle outside and crawl through the skeletons of burned-out lorries, trampoline on rusted box-spring mattresses, or hide in a stray bathtub that lay abandoned amid the rubble.

Michael spent most of his time thinking about pigeons. Dating back to the nineteenth century, the pigeon had been known in Ireland as ‘the poor man’s racehorse’. Michael’s father and his older brothers introduced him to pigeons; for as long as he could remember, the family had kept birds. Michael would set out into the combat zone, searching for roosting pigeons. When he discovered them, he would take off his jacket and cast it over them like a net, then smuggle the warm, nervous creatures back to his bedroom.

On his adventures, Michael sometimes picked his way through derelict houses. He had no idea what dangers might lurk inside – squatters, paramilitaries, or bombs, for all he knew – but he had no fear. Once, he came upon an old mill, the whole façade of which had been blown out. With a friend, Michael scaled the front, to see if any pigeons might be roosting inside. When they reached an upper floor, they suddenly found themselves staring at a team of British soldiers who had set up camp. ‘Halt or we’ll fire!’ the soldiers shouted, training their rifles on Michael and his friend until they clambered back down to safety.

About a year after the Falls Curfew, Michael’s father began to lose a great deal of weight. Eventually, Arthur grew so weak and shaky that he could no longer hold a cup of tea. When he finally went to see a doctor for tests, it emerged that he had lung cancer. The living room became his bedroom, and Michael would hear him at night, moaning in pain. He died at home on 3 January 1972. As Michael watched his father’s casket being lowered into the frigid ground, he thought to himself that things could not possibly get any worse.