Читать книгу Fabulous Fred - Paul Amy - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

6

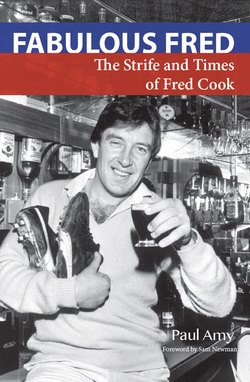

ОглавлениеFRED Cook started at Port Melbourne in 1971. By the time he finished in 1984, he’d become a towering figure at the Borough and in the VFA, a full forward who was as popular as he was prolific in front of the goals.

He topped the century seven times on his way to 1236 goals, featured in six premierships, captained the club and Victoria, won a best and fairest, and made a record 253 appearances.

He had turned his back on league football, unwisely, thought people in a good position to judge. But his public profile would soar in the VFA and eventually exceed those of many VFL players.

Cook seemed to be everywhere: on Channel 7’s World of Sport, reading out the teams at radio station 3DB, and writing for The Sporting Globe and The Sunday Press. He was also a regular on the sportsman’s night circuit, often accompanied by his pal Sam Newman. They’d turn up, tell a few funny stories and answer some questions. And they’d leave with a few beers under their belts and a few hundred dollars in their pockets.

Few players could land a page 1 photo on the big-selling Sun News-Pictorial, as Cook did in 1978. He had visited a kindergarten in East Bentleigh, and snaps of the burly footballer in full playing gear mixing with the littlies made for a spread in the middle-pages: ‘Fred shows ’em how’.

Flamboyant from top to toe, he was a poster boy for the association, bringing it untold publicity. The VFA made it official when it put him on the payroll as a promotions officer, with executive director Keith Mills saying Cook was as well known among junior footballers as Alex Jesaulenko and Kevin Sheedy.

In a competition crowded with hard men, he bunched his fists only to celebrate his goals (he went through his long career without being reported). Cook had more than enough teammates who could ping away punches when things got willing. The archetypal Borough was as fearless as he was ferocious.

‘Fred Cook was more of a matinee idol than a football star,’ sports writer Garry Linnell said of Cook in 1990. ‘It seemed he was there on television every Sunday afternoon, taking a big grab, kicking a match-winning goal.’

Some veteran supporters dared to mention him in the same breath as Port’s legendary 1950s All Australian ruckman Frank Johnson, who went to South Melbourne late in his career and won the best and fairest in his first season.

As for younger fans, they wore Cook’s No. 5 on their blue and red jumpers, and thrilled at his every exploit. At siren’s end they would besiege him with pens and paper, and he took care to give autographs to all of them. He knew some were from battling families. Football was their weekly highlight and he was their hero. Cook arranged for a printer to run off hundreds of copies of his photograph in his Port Melbourne jumper. He would write a personalised message for any boy or girl seeking his signature.

Alan Wickes, president of the VFA from 1981 to 1984, noticed how well Cook treated his fans, stoking his popularity. When he thinks of Cook, he pictures him on the ground ten minutes after games, signing youngsters’ jumpers.

‘There were a lot of little No. 5s out there,’ Wickes says. ‘But Cookie looked after them. When he was signing for a kid he was probably talking to the dad as well. And that’s a very humane thing, isn’t it? That’s why he was so loved. That was Fred. He wanted to please everybody — but that was probably his weakness.’

After one match, Cook left the field bloodied from a frustrated full back’s fist. His father arranged for him to be stitched. ‘The doctor’s ready,’ he said, motioning him to the rooms. But Cook was surrounded by dozens of young fans. He couldn’t let them down. ‘How can I walk away from this? Tell the doc to wait a bit,’ he said.

More than a few single mothers asked Cook to have a quiet word with their rebellious sons. When he did, their behaviour invariably improved. One lad, who had been refusing to attend school, was startled when his idol turned up at his door and told him it was important he put time into his studies. Picking up his bag, off he went.

At one stage, Cook earned the sobriquet ‘Kissing Fred’. It started when he began greeting his daughters with a peck on the lips as he came off the ground. Soon other littlies were lining up for a smooch. ‘It is like a visit from royalty with Fred bestowing kisses, smiles and head-pats all-round,’ wrote The Herald’s Alf Brown.

Port Melbourne didn’t have to wait to see Cook at his best when he crossed from Yarraville. Under the coaching of former champion Borough forward Bob Bonnett, the recruit polled twenty-four votes to finish fifth in the J. J. Liston Trophy, five behind the winner, Preston’s former Collingwood player Laurie Hill.

Playing all eighteen games, mostly at centre half back, he was second to Jim Buckley in the club best and fairest. Norm Goss junior, who would go on to be a first-class league rover, was third.

But the Borough dropped from third in 1970 to sixth in 1971. Bonnett retired at season’s end. The club’s annual report noted he ‘did his utmost to bring success to the club, but his efforts to win games, at times, fell on deaf ears. It was certain to all supporters that if his instructions had been heeded at all times Port could have easily finished in the final four’. The club hired tenacious 1968 Carlton premiership player Ian Collins to replace him.

Although he had despised it, Cook immediately felt at home at Port Melbourne. Teammates became mates. Supporters smarted over defeats, but were loyal, slapping his back on days good and bad. Mostly, they were good, and it was common for diehards to thrust money into Cook’s hand after games.

After he had performed well in one match, an old-timer on a walking frame inched towards him in the rooms. ‘I thought you played well today, Fred,’ he said, passing him $2. Cook told him to save it for a day when he played poorly. The next week, after Cook found kicks elusive, the supporter reappeared and stabbed the money into his hand. He has never forgotten it.

‘Once you put on that jumper, you were part of a family, the Port Melbourne family,’ he says. ‘I actually felt like I’d been adopted. Mind you, plenty of people reminded me you weren’t a local until you’d put in ten good years. It was a different time back then. Port had the firsts, the seconds, the thirds and the fourths, and if you were a kid growing up in Port Melbourne and you had a bit of ability, you wanted to play football for Port Melbourne. And, by geez, when they got there they’d do anything to win. That’s what made the club so strong. They played for the jumper, right up to the final bell. And Old Man Goss [Norm Goss] looked after everyone.’

Premiership men including Gary Brice, Bob ‘Bullwinkle’ Profitt, Graeme ‘Arms’ Anderson, Vic ‘Stretch’ Aanensen, Graham ‘Buster’ Harland, David ‘Sam’ Holt, Billy Swan and Greg ‘Biff’ Dermott were examples of locals rising to senior ranks and becoming distinguished servants. Brownlow Medal champion Peter Bedford was another.

Brice grew up in Liardet Street, so close to the North Port Oval that he could hear the roar of the crowd on Sundays. He watched Port most weeks and Bonnett was his idol. When mates at school asked him which team he supported, he always said Port Melbourne, not a league side. He started playing for the Port seconds in 1966, after his secondary schooling. Bonnett was captain and coach of the team. Brice had an outstanding league career at South Melbourne and steered the Borough to the 1980, 1981 and 1982 premierships, but he says playing alongside Bonnett was a highlight of his career.

‘What Fred says is exactly right,’ Brice says. ‘It was ingrained in all the kids in Port Melbourne — that was the club to be at. We were in South Melbourne’s zone but they weren’t having a lot of success, so it was always a case of, if you were going to play good football, you were going to go to Port Melbourne. It was a burning ambition of mine to do it.’

When Cook and other players talk of their time at Port, they invariably speak with affection and admiration for Norm Goss.

Watching football at North Port Oval, you take a seat in the Norm Goss grandstand. It overlooks a ground with a white picket fence and carries the eye to surrounding factories, and beyond them a glimpse of Melbourne’s skyline.

The grandstand is named after a man who served Port with tenacity as a player and with distinction as a straight-talking administrator who put the club’s interests above all else. The ground was his second home; if he wasn’t at the family residence in Clark Street (where he and his wife, Lillian, raised nine children), he was at the club.

Norm Goss played in Port Melbourne’s 1940 and 1941 premierships, alongside Tommy Lahiff, with whom he formed a lasting friendship. Lahiff took over as coach of the Port team after the resignation of Frank Kelly shortly before the 1941 finals. Up against Coburg in the decider, Lahiff devised a plan to stop champion Burgers full forward Bob Pratt. It required courage on the part of Goss.

‘Full back Lance “Diver” Dobson was to stick close to the dangerous Pratt, and rugged back-pocket player Norm Goss was to assist Dobson by blocking Pratt’s path and stalling his spectacular leaps at every opportunity,’ wrote Ken Linnett in his outstanding biography of Lahiff, Game for Anything. ‘After the match Goss’s back was a patchwork of stop marks from the boots of Bob Pratt, but he and Dobson had obeyed instructions with vigour and skill.’

Goss had stints at South Melbourne and Hawthorn, playing eight senior games for the Hawks in 1942 and 1943. He returned to Port Melbourne, was elected secretary in 1947 and held the position for three decades. He also gifted the club four senior players: Norm junior, Paul, Kevin and Michael. But he did not set out to make his sons Borough players. ‘I just told them that if they were frightened they should become an umpire,’ he once said.

Norm junior, Paul and Kevin played league football, with Norm winning a best and fairest at South Melbourne and figuring in Hawthorn’s 1978 premiership.

Cook came to think of Norm Goss as his second father.

‘Old Man Goss? Wonderful man, wonderful man,’ he says. ‘I’d nodded to him a couple of times, but I’d never met him before he asked me to play at Port. Soon saw what a great human being he was. He didn’t drink, he didn’t smoke, he was a good Catholic, he had about twenty-seven kids! He ruled that club very firmly — you couldn’t push him back an inch, even with a bulldozer — and his word was everything. By geez, it was. I had a handshake deal with him. That was enough for me.’

Brice says Goss was not only a great administrator, but a fine spotter of talent. Careful not to pay more than the club could afford, for years he did most of the recruiting, assessing the needs of the team and finding players to strengthen it.

His mere presence on the interchange bench during matches was enough to motivate the Borough. ‘He was respected so much that it was often about not just winning, but trying to do the right thing by Norm,’ Brice says.

When Cook was entrenched at full forward, Goss would approach him before the game. If it was muddy and wet he would say Port would win if he could manage four goals. When conditions were better he would set a target of eight. Cook, never wanting to let him down, set his mind to it.

‘That was his way of geeing me up, setting me a benchmark,’ he says. ‘If I did my job he might give me a nod of approval. He was a hard marker. If I kicked ten he might say, “You did okay today, pal.”’

Norm Goss junior says his father thought highly of Cook, who was a regular visitor to the Goss home, often dropping in for a cup of tea and a chat before training.

‘The old man and Fred were pretty close,’ Goss junior says. ‘Good mates, you could say. Fred was always himself around the old man. He was a character, a huge personality. Confident.’

Norm Goss could be pleased with his prized recruit’s first season at the North Port Oval.

Cook, playing mostly in the backline, had a season haul of 433 kicks (and only twenty-six handballs!) and 219 marks. He also kicked twenty-three goals, an appetiser for the feasts that followed. Four came against Prahran. After one, he was photographed raising both hands in triumph, a Two Blues defender dropping his head in disappointment. It became a familiar sight at VFL grounds.

Bonnett, now eighty-one, says he played Cook forward occasionally, and would have done more often but for his desire to ‘be in the play all the time’.

‘Because he was such a good mark, a wonderful mark in fact, he was always going to be dangerous in front of the goals,’ he says.

But Bonnett, twelve times Port’s leading goalkicker, could not have imagined that the player he laughingly remembers as a ‘lazy bugger who loved the limelight’ would surpass his tally of 933 goals. They were kicked, it must be pointed out, in more congested eighteen-a-side football and a low-scoring era.

When Port named its team of the century in 2003, Bonnett was in a forward pocket and Cook at full forward.

‘Fred wasn’t the best kick in the world, but he never went far from the goal square,’ Bonnett says. ‘There he could take his marks, and go back and put them straight through.’

That was all to come. A strong first season in Borough blue and red behind him, Cook looked forward to playing under Collins in the 1972 season. But a heart attack flattened him like no opponent could.