Читать книгу Fabulous Fred - Paul Amy - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

ОглавлениеFRED Cook is back in Frankston Magistrates’ Court in late March, 2014. But, having shaken his drug addiction a few years earlier, he is in far better shape than during his appearance there in 1991. At age sixty-six, he is looking pretty well for a man who has subjected his body to years of abuse. He carries a few extra kilos around the stomach, but nothing a few strolls around the block wouldn’t fix.

He thinks he will be walking soon enough. Cook is in court for driving while disqualified. Twelve months earlier he’d been given a four-month jail term, suspended for two years, for the same offence and his long-time lawyer, Bernie Balmer, is warning him that he is facing prison. Cook’s list of prior convictions for road-related offences runs to five pages.

Before mention of his case, Cook sits on the steps outside the court. He sucks on a cigarette as he flicks through the Herald Sun newspaper, settling on a photograph on the Confidential page of Sam Newman hamming it up with Footy Show colleague Shane Crawford.

He is sitting in sunlight, perspiring. ‘I’ve got a headache and I’m worried,’ he is saying. ‘I mean, Christ, there were times I should have done time and didn’t. They could have locked me up and thrown away the key. But I shouldn’t do it over this.’

His mobile phone rings. It is his son Jordan wanting to know how he is getting on.

‘What do you mean “old man”? I’ll give you old man! Yeah, good, good, good. Haven’t gone in yet. Just sitting outside having a smoke. Bernie’s already in there. Let’s hope he can work his miracle, hey? Come on Bernie, work that miracle.’

A short time later a middle-aged woman approaches. ‘What are you doing, you silly old bastard?’ she asks, laughing. Cook explains the driving offence. The woman replies that her partner, answering a charge of making threats to kill, had been arrested with trafficking marijuana as soon as he arrived at court. The woman and Cook go back a long way. He knew her husband, who had died of a heroin overdose about twenty years earlier.

Just before 10am, Cook walks to the court entrance, places his phone, car keys, cigarettes and a large blue diary into a plastic container, and is scanned through security.

His case is to be heard in court two, where the spiky-haired, moustached Balmer is seated at the bench talking to another defence counsel and the police prosecutor.

Cook nods at Balmer, takes a seat in the back row and begins to read the newspaper again.

He immerses himself in it as a few cases are heard: an eighteen-year-old woman up on ninety-six theft charges, a middle-aged man trying to shake a fraud charge over an insurance claim for damage to his car, and a younger man charged with the sexual assault of his former partner.

‘The matter of Frederick Williams to court two please,’ the female clerk says finally. Frederick Williams is Frederick William Cook. Fifteen years earlier, seeking to overcome a bad credit rating, he had changed his name by deed poll. An hour later he was opening bank accounts and being offered credit cards.

Cook has been fretting about the hearing for weeks, fearing another spell in prison. The case had been adjourned a few times while Balmer sought a psychiatric assessment and a pre-sentencing report.

Now he asks magistrate Anne Goldsbrough if he can ‘be so bold as to seek another adjournment’. There have been delays in receiving the reports and, mindful of the suspended sentence and seeking to highlight ‘exceptional circumstances’, he is reluctant to proceed without them. He says one doctor had told him ‘incarceration would be detrimental to his [Cook’s] mental health’.

The magistrate agrees to hear the case in May. She tells Cook he is free to go.

‘Keep up the good work, Your Honour,’ he says, raising laughs around the bench. And with that, the old showman emerges: Cook smiles, rises to his full height, puffs out his chest and heads for the door with the swagger so often seen at VFA grounds.

Thirty minutes later, Cook and Balmer have coffee across the road from the court. Balmer, often described as a ‘knockabout’ criminal lawyer and with a client list including Mark ‘Chopper’ Read and Mick Gatto, first represented the former football champion in the late 1980s. He remembers it vividly. Facing drug charges, Cook was given a good behaviour bond. ‘Your Honour, you can give me a bond for the next twenty years because I won’t be coming back to court,’ he told the judge.

But since then he’s had to call on ‘Bernie The Attorney’ at least once a year. Balmer regards him more as a friend than a client — they talk two or three times a week, even when he’s not in trouble — and he has taken on his latest driving offence on a pro bono basis. Cook is promising to ‘sling you some money down the track’. But the lawyer isn’t exactly factoring it into his end-of-financial-year accounts. When people speak to him about Cook and observe he’s led a remarkable life, Balmer corrects them. ‘Mate, he’s led three lives.’

WHEN you mention Fred Cook to people who haven’t seen him for a while, they invariably respond with a question: ‘How is Freddie?’

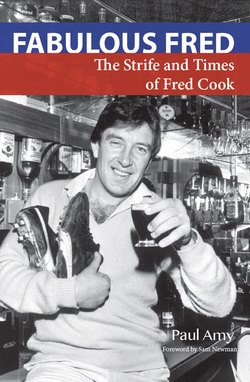

You suspect they really want to ask, ‘Is he off drugs?’ They are pleased to hear he hasn’t used for a few years. Cook was on amphetamines for more than two decades. He has long been removed from the lifestyle he enjoyed as a football and media figure and the proprietor of the Station Hotel in Port Melbourne.

When old friends saw him after his slide it was usually on the TV news, after he had been arrested or dealt with in court. He was inhabiting a world they didn’t recognise and they felt powerless to pull him away from its orbit.

Yet affection for him has never wavered. People who know him well speak of a sociable man who was always generous with his time and money at the peak of his popularity. They acknowledge his flaws and foibles — his self-destructive streak and tendency to take things to excess, an ability to sniff a short-cut and an immaturity apparent when he casually sprinkles his female conquests into conversation (his wife, Sally Desmond, says he’s sixty-six going on fifteen; his sister Pam says he never grew up). But they describe him as a ‘loveable larrikin’ or ‘scallywag’ or ‘likeable rogue’ with a capacity to lighten the mood around him. They wish only the best for him.

‘Mate, I wasn’t saddened by what happened to Freddie. I was heartbroken,’ says his former school mate and Footscray teammate Ricky Spargo. ‘Such a lovely bloke and to see him go down like that … We all loved the bloke. My mum’s 101 and she’s loved him all her life, like my old man [former Footscray player Bob Spargo] did.’

He can barely talk about Cook’s post-football life. ‘Nah, can’t cop it. That wasn’t my Freddie.’

Spargo was thrilled to learn Cook was doing okay. He hasn’t seen him for a long time, but thinks of him often and always fondly. He doubts there is a bad bone in his body.

Balmer holds the same opinion. He says Cook did and still does put friends first. ‘Nothing he’s been through has knocked that quality out of him,’ he says. ‘He looks out for others more than he looks out for himself, and as a consequence of that he’s left himself destitute. And it’s sad, just tragic.’

Former Port Melbourne coach Gary Brice was devastated as he watched Cook’s life unravel. He speaks about him with the warmth that football coaches reserve for players who won them premierships. Cook played in three flags under Brice.

‘It was a disappointing period of his life. Very disappointing,’ he says. ‘Hopefully he’s got it under control, because I guess with that sort of addiction you never get over it. It’s something you have to live with and manage through your life.’

Cook is living on the Mornington Peninsula, where he headed with his future wife Sally Desmond after he was arrested for drug offences for the first time, in 1986.

But he cannot tell a redemption story, a tale of emerging stronger from a wretched experience. It’s a daily struggle to stay clean. He has said it hundreds of times: ‘I didn’t use yesterday, I haven’t used today and I probably won’t use tomorrow.’

If someone produced white powder, a spoon and a clean needle and told him he could use with no consequences, away he’d go, jabbing his arm as quickly as he could. But he knows the consequences only too well.

In the beginning he took speed to keep up with his many commitments, time management in powder form. A few months earlier he had been asked to retire from Port Melbourne, his footballing home for fourteen years. He says now that drugs were his way of substituting the surge of adrenaline that came from kicking hundreds of goals and winning premierships.

It’s a familiar tale: a feted sportsman losing his way after his career ended and the cheering had stopped. Few fell as far or spectacularly as Fred Cook. In his later years, when he should have been speaking about his career or commenting on football affairs, he was trotted out to talk about criminal figures, including Kath Pettingill for the special The Mother of Evil. He told how she marked one lot of foils green (for amphetamines) and others red (for heroin) when her son Dennis Allen was shifting drugs at a furious rate in Richmond in the 1980s.

Allen had money falling out of his pockets then. Cook says he would be equally flush if he had a dollar for every time he’d been told he had the world at his feet — and squandered it. ‘Pissed it away,’ is how he puts it. His regret runs deep, but he tries to suppress it, thinking he’d go mad if he brooded over his many mistakes. Besides, he says, it’s hard enough to deal with the present, let alone the past.

COFFEE and conversation with Balmer drained, Cook returns to the Ministry of Housing property he has occupied for seven years, a run-down three-bedroom house. The rent is $100 a week. When times were good it wouldn’t have served as a backyard shed for the spread he had in Dendy Street, Brighton, one of Melbourne’s most exclusive suburbs.

‘They’ll demolish it soon,’ Cook says, opening the front door. ‘Well, hopefully they’ll demolish it. Have a look at the joint.’

It reeks of neglect. He will not be sad when he has to move out, but he will miss the space it affords him to store his children’s possessions. All manner of goods have piled up in the front bedroom.

The red four-door Nissan Pulsar he was driving when police pulled him over twelve months earlier is parked in the driveway. He bought it from a dealer from nearby Hastings for $700 with twelve months’ registration and says he hasn’t checked the water or oil for a year. ‘I put some air in the tyres last week, but that’s about it,’ he says. ‘I’ve bought a few cars off this guy. As I said to him, they all broke down and it was about time he sold me a good one. It goes, I suppose.’

A well-groomed Malamute dog named Chewie and two cats hover around Cook as he sits and talks animatedly. His tongue was always turbo-charged, stories gushing out of him like a tap. Trapping them is like trying to catch sunlight in a jar. He leaves a lot unfinished before launching into another.

Sally Desmond, from whom he’s been separated since 2004, apparently asked him to look after the dog for a few days. ‘That was six years ago and she’s still here,’ Cook laughs, lighting up a cigarette. ‘Can’t get rid of her. Can’t stop her eating the cat food either.’ But he admits he likes to have the animals around.

Cook lives quietly, drawing an aged-pension every fortnight and trying to make it last. Sometimes he will buy two cans of Bourbon and Coke or a beer. But he has to stretch every cent.

A year earlier he was better off. He was working on the big Peninsula Link roads project, counting trucks and jotting down registrations as they came and went with landfill. Taking home about $2200 a week, he could slip something to the youngest of his seven children.

‘You know how it is. “Dad, I need a new phone. Dad, I need my nails done.” So what do you say? You say, “How much do you want?”’

Before the Peninsula extension he did general labour on the Eastlink road development, and drove an earth-moving truck when the Mount Martha Cove Marina was under construction.

The physical work explains why he looks reasonably fit. But he says he’s on a ‘bucket’ of medication, mainly for a heart condition and high cholesterol. It can leave him lethargic. He also suspects it contributes to his mood swings. He will be happy for a week, then overcome by sadness for a day or two. He says he can distinguish between sadness and depression, and he never feels depressed.

Cook likes to have an early breakfast — toast and coffee, and two cigarettes — and watch the ABC News 24 station on the shiny, large flat-screen television in the lounge. News and documentaries hold his interest.

Surprisingly, for a man known to have a leviathan eye for the ladies, he says he’ll take female company as it comes.

He’s committed only to doing as he pleases. ‘I’ll go down to Tasmania and propose to Bob Brown before I get married again! I’m used to doing it my way. I’ll get out of bed when I’m ready. Cook a steak when I feel like it. Have no-one to tell me to piss off outside to smoke. Whatever suits me.’

Cook speaks to his three children with Desmond — Jarryd, Jordan and Jaimee — most days, and often natters with his great mate Newman. They were opponents on the field and clicked like Lego pieces off it. He concludes every phone call to Newman, as he does most people, with the words, ‘Love ya, see ya, bye’. And when he calls people he knows well and will laugh off his bullshit, he’ll often greet them with, ‘Fred Cook, superstar, here.’

Now and then he catches up with old pals. A few days in to 2014, he had lunch with Balmer and retired sports journalist Scot Palmer at Sorrento. A month later he shared a beer with former Richmond players Tony Jewell and Mal Brown.

‘But honestly, I don’t get out much. I sit around watching the TV. Watch too much of the bloody thing. I’m going to have to get off my arse and do some exercise. Went and had my heart checked and they put me on one of those treadmills. I could only stay on it for seven minutes and ten seconds!’

Even when he was in his physical prime he wasn’t much of a runner. At Port Melbourne he stayed close to the goals, living on his marking. All his former teammates say it: he was a lousy kick, but he had the best hands you’d see on a footballer. The ball got lost in them.

There is little in the house to indicate Cook was a football great. No trophies or premiership medals are on display. He’s unsure what happened to them.

A 1970s poster promoting the VFA as the cradle of community football is taped to a lounge room wall. A fit, strong and smiling Cook stands in the front row, his first son Nathan at his feet. He recognises Sandringham’s Terry Wilkins and Prahran’s Kim Smith as among the other players in the poster.

But ample reminders of the days when he ruled VFA goal squares can be found in the worn blue suitcase he keeps. A fading Ansett baggage tag hangs off the handle. When Cook was on drugs he jumped frog-like from house to house. But he always took the suitcase with him.

Cook opens it to show a few yellowing newspaper clippings, a handful of VFA Recorders, photographs and a falling-apart scrapbook he believes was maintained by a sister. Pieced together, it marks his rise from Footscray Tech Old Boys to league club Footscray, his controversial transfer to Yarraville in the VFA, an equally headline-taking move to Port Melbourne, his many triumphs in Borough red and blue, and his drug-fuelled demise.

It also has evidence of his time as a media man. Newman, Cook, footballer writer Greg Hobbs and ex-Carlton rover Adrian ‘Gags’ Gallagher are splashed on the front page of the mid-week edition of the pink-papered Sporting Globe of 29 March 1978.

‘Here’s our team,’ the Globe trumpets. Cook is described as the ‘prolific Port Melbourne goalkicker and VFA’s biggest drawcard’.

Cook snaps the suitcase shut and points out what he calls his most prized possession from football. It’s a small medal that hangs off a long screw on a doorframe in the kitchen.

It was awarded to him in 2007 for serving as an assistant coach and goal umpire for the Kangaroo Flat Primary School side that won a lightning premiership in Bendigo. Jaimee, his youngest child and third daughter, played in the team.

‘It would be nice to win one game,’ Cook remembers the school sports master telling him before the first match.

‘I said to him, “Stuff that, let’s win every game.” Wouldn’t believe it but they won six out of six and finished up with the premiership. Could have cried, I was so proud.’ He left the presentation with the words made famous by his childhood hero and adult pal Teddy Whitten: ‘We stuck it up ’em!’

He was similarly proud when son Jarryd came second in a league best and fairest on the Peninsula. That year they were living together in a caravan and Cook was still doing drugs. He was so broke he sometimes went to service stations to steal sandwiches for his boy to take to school for lunch. They often used to joke that when the world ended they’d be the only survivors to keep the cockroaches company.

Cook has little interest in big football, regarding it as a ‘sheila’s game’ with a defensive element that bores him. ‘Can’t be bothered with it. Years ago there was room for everyone: the superstars, the chubby kid who knew how to get the ball, the thugs. They stuffed all that up. Same with how they play. What’s wrong with kicking it long down the guts?’

Like many old VFA followers, he barely recognises its replacement, the VFL, a blend of traditional association clubs and AFL reserves teams.

The golden years of a competition he helped make so popular have long passed. But he’s pleased that Port Melbourne, after alignments with the Sydney Swans and North Melbourne, has survived as a stand-alone entity. He mingled with players and supporters after Port’s grand final victory over Williamstown in 2011. The team went through the season unbeaten, something that was beyond the great Borough sides Cook served.

For a long time Cook stayed away from Port out of embarrassment. He thought his drug use and stints in prison brought shame to a club he loved and was proud to call his footballing home. But now he gets to one or two games a season and is on the mailing list for the past players’ newsletter. He mostly stays in touch with Brice and premiership teammates Tony Ebeyer and Billy Swan.

Mention of Swan has him dusting off memories of the 1976 grand final. Famously, Dandenong defender Allan Harper decked Cook after he got on the end of a Swan kick and nonchalantly poked the ball through the goals. Wild scenes followed. Intent on retribution, Port players went flying in at Harper. At the other end of the ground, rugged Borough George Allen put down Dandenong forward Pat Flaherty.

ATV-O commentator Phil Gibbs described the mayhem. ‘Cook’s been flattened and it’s right on! Harper is in trouble. Let’s watch this. And another player has been flattened at the other end of the ground! Flaherty’s been flattened at the other end! And there’s another one down! A trainer’s gone down!’

A minute later, Cook, blood pouring from his mouth, waved away the trainers and theatrically raised his hands as if to say, I’m okay, let’s get on with it. Cook was never a fighter on the field. He didn’t have to be. Port had strong men who could thrash away with the best of them.

Swan has often said to Cook he would have avoided Harper’s harpoon if he’d let the ball bounce through the goals.

‘Swanny always brings it up,’ Cook says. ‘Calls me a selfish bastard and says I should have shepherded it through. Blames me for all that shit that went down.’

After watching a clip of the incident on YouTube, Cook stays silent for a few seconds, appearing emotional.

‘Just reminiscing,’ he says. ‘I tell ya, they were fucking good days. Should have been there.’