Читать книгу Fabulous Fred - Paul Amy - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1

ОглавлениеIT had been an unremarkable day in the Frankston Magistrates’ Court.

Locals, a few of them carrying the whiff of aftershave and looking uncomfortable in just-bought suits, had come to answer charges like drink-driving, burglary and theft. They filed in before 10am and they hoped their solicitors would ensure they filed out.

Quick-with-a-quip prosecutor Ricky Lewis would have called it a ‘mixed bag’ of cases, as he invariably did when quizzed by the reporter covering proceedings for the Frankston Standard newspaper.

Most cases were heard in court one, in a building that stood for years on Davey Street, only a couple of decent drop punts from the Frankston football ground. But around lunchtime on this day in December 1991, court staff began to murmur about a matter to be heard in the smaller second court.

A former footballer had been arrested, they said. Big name in his day, apparently.

A few minutes later, uniformed police marched a handcuffed and dishevelled Fred Cook in to court. Sweat beaded on his forehead. He wore jeans that needed a wash, a similarly grubby white shirt and running shoes on their last legs.

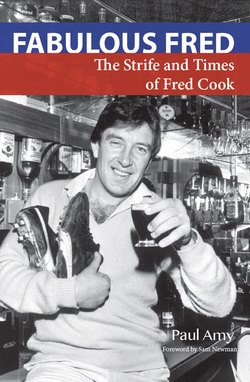

Some wouldn’t have recognised him as the man who less than a decade earlier was the most captivating and colourful player in the Victorian Football Association (VFA). Supporters called the prolific Port Melbourne goalkicker ‘Fabulous Fred’. He assumed the profile of a pop star.

Police had come to know him well, too, but as Frederick William Cook, repeat offender. To them he was no football hero. He was just another sloppy crook who needed locking up. ‘Fred Cook? Can’t stay out of trouble. He’s a pain in the arse,’ an officer from the Frankston District Support Group once replied when asked about the former Port champion.

A pin-up boy to an ocean of small fry, Cook kicked bags of goals in his sponsored Puma boots and was integral in six Port Melbourne premierships during the historic club’s most successful era.

Its successor, the Victorian Football League (VFL), has struggled for publicity for years. But the VFA had a large and fanatical following in the 1970s and 1980s — it was common for fans to support a league team on Saturdays and an association team on Sundays — and a cluster of great players and compelling characters. There was Dandenong spearhead Jim ‘Frosty’ Miller. Feared Preston ruckman Harold Martin. Cook’s Port Melbourne teammate and champion big man Vic ‘Stretch’ Aanensen. Bearded Coburg swashbuckler Phil Cleary. Rugged Sandringham defender Alf Beus. Geelong West sharpshooter Joe Radojevic. Long after retirement, their names still resonate with seasoned football followers.

But Cook had the largest profile of all. Wearing the No. 5 jumper from full forward, he was the finisher for a team as bruising as it was brilliant. With his regular starring roles in matches televised by Channel 0, he helped haul the VFA out of the shadows and into the spotlight.

The Encyclopedia of League Footballers, recording Cook’s thirty-three games for Footscray between 1967 and 1969, described him as ‘one of the greatest stars to have played in the VFA’, formed in 1877. ‘His goalkicking feats with Port were legendary,’ it said.

Former Footscray champion Doug Hawkins said, ‘He was the king of the VFA, Freddie, the absolute king.’

And he had charisma bursting from his boots. ‘Although he appeared apologetic about the manner in which he humiliated opponents, the cameras were drawn to him,’ Cleary wrote in his book Cleary Independent. ‘At after-match gatherings, he wandered through the throng like a film star.’

Women loved him, and he them. He had a legion of ladies, including the daughter of a country’s Prime Minister and a television soap star. His great mate Sam Newman’s reputation as a ladies’ man endures. But he says he had nothing on Cook.

With the popular Station Hotel in Port Melbourne (home to Melbourne’s most glamorous strippers, all cherrypicked by Cook) and newspaper, radio and TV gigs, he had the wealth to go with the adulation. But the famous footballer with the larrikin streak who mixed with Melbourne’s sporting and entertainment elite became infamous for his drug use, his association with some of Melbourne’s most notorious criminals and his spells in prison. He went from hero to zero in three years.

Cook had a gun put to his head. He was badly bashed when his associates thought he’d turned police informer. Newman was there to save him, and calls it the scariest day of his life. Cook witnessed violent assaults. He himself struck women. He went to his mother’s funeral drugged to the eyeballs. He would inject himself in school yards ahead of lectures to students about the perils of drugs and alcohol.

Sitting in jail in a period of sobriety, he reflected on how far he’d fallen and how much he’d hurt his family. It was Christmas and he was aching to see his kids. He thought about killing himself.

Cook can pinpoint the start of his slide. One night he was battling the flu ahead of a sportsman’s night alongside the St Kilda Brownlow Medal champion Neil Roberts and English fast bowler John Snow.

Hardened Melbourne criminal Dennis Allen, who’d started hanging around the Station, whipped out a bag of white powder and a pen knife and tipped some amphetamines into his drink. Cook immediately felt a burst of energy, and was ready to fulfill his engagement.

Up until then he’d relied on strong coffee (sweetened by five sugars) and cigarettes to stay ‘up’.

But, with his every day crowded with work commitments, he began to lean on speed, and eventually his life fell apart. He admitted the drugs were a way of replacing the adrenaline rush football brought him. Cook lost everything he owned, and resorted to drug pushing and petty crime to get by.

Where once he featured in the sports pages for his deeds on football grounds, he now filled headlines in the news section for his court appearances. ‘Footy star on drug counts’. ‘Drugs bring down footy great’. ‘Cook on bond over drugs’. ‘Drugs nearly killed me — Cook’. ‘Footy hero Cook jailed’. They piled up like rubble around a wrecking ball. In May 1989, he went before the Victorian County Court for drug trafficking and deception.

His legal counsel, Bruce Walmsley, told Judge Hanlon that Cook had ‘demonstrated himself to be a pathetic figure’.

The judge released him on a bond and suspended sentence, commenting: ‘In the end I have come to the view that the pathetic mess you made of your life by the use of the drug in which you trafficked is clearly a sufficient example to the community.’

Flanked by his de facto wife, Sally Desmond, Cook stood outside the County Court and declared he was going clean.

He’d lost his business and the respect of his family and friends, he said.

‘Have I learned a lesson? Is the Pope a Catholic?’ he said to reporters.

‘If anything, it’s a lesson to young people. If it isn’t a lesson, I don’t know what is. I certainly will not be dabbling in any more drugs.’

He said the same in an extended interview in the Sun newspaper with his pal and television colleague Newman the following year. ‘I can’t help anyone else until I help myself, but the life I lead is now way behind me and will never happen again.’

But it did, again and again. His list of convictions would eventually extend to twelve pages.

Newman, and many others, pleaded with him to apply to his life the discipline he showed in his football career. Cook was unable to act on the advice. He had believed he could use drugs to his advantage, squeezing a few extra hours into his busy days, but they took a sinister hold on him. He kicked hundreds of goals, but he couldn’t kick his drug habit.

In April 1990, he was sent to prison for twelve months after breaching the suspended sentence by swiping cement and timber. He was working as a handyman and needed the materials to finish a job and provide for Desmond and their two-year-old son. The man who once put $10,000 a week into his pocket as a publican was now scratching to pay for nappies and milk.

After serving his time at Morwell River Prison Farm, Cook again swore he would stay out of trouble.

But old drug habits die hard. A few months later police searched his home and found amphetamines and cannabis.

Then came his appearance at Frankston Magistrates’ Court. Police had performed another raid and found more amphetamines and $10,000 worth of stolen goods, a booty they called an ‘Aladdin’s Cave’.

Hooking up with young crooks, Cook had been swapping drugs for stolen gear for a month, stockpiling it in a unit. He was running it like a small business, keeping a ledger of the comings and goings.

It led to another stretch in prison. By that stage there was nothing fabulous about Fred. The champion spearhead who a few years earlier was surrounded by famous faces and adoring supporters had only four hard walls for company.