Читать книгу Richard Mulcahy - Pádraig Ó Caoimh - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface and Acknowledgments

This book is a study of two interrelated processes which transpired during the revolutionary period of Irish national liberation, 1913–24, namely the politico–military career of Richard Mulcahy and the struggle for supremacy within the nationalist elite, especially the struggle for supremacy on the vital question of the nature and extent of the emerging government–army relationship.

As can be gathered, then, in trying to assay the interrelationship between a complex man and a complex topic by dint of accuracy of fact and opinion, an amount of research had to be undertaken. To that end the Mulcahy Papers, which were readied by the man himself and his family during the last ten years of his life in preparation for transfer to University College Dublin’s Archive Department (UCDA), and which offer an abundance of primary source material, especially on the period, 1916–24, were the wellspring of information for me.

Notwithstanding, there was but a relatively negligible amount of private correspondence available in UCDA. Similarly, in regards to the letters he reputedly wrote on a regular basis to Jim Kennedy, his long-term IRB friend from Thurles, a search of the extensive Brother Allan Papers in the Military Archives of Ireland (MAI), wherein merely a small number of pamphlets exists in what is termed the James Kennedy Papers, and a search of the Christian Brothers’ Archive turned up nothing.

Still, at UCDA, I was able to find Mulcahy’s thoughts in his intermittent diary-type notes, his official communications and memoranda and his memoir-type publications, as well as in the tape-recorded conversations he had during the 1960s with former comrades and with his wife, Min, and son, Risteard. I was also able to find references to him in the Cabinet minutes and state paper deposits of the National Archives of Ireland (NAI). Moreover, by means of the wide circle of family correspondences which are available in the Ryans of Tomcoole Papers, as well as in Min’s own personal correspondences in the uncatalogued Min Ryan Papers in the National Library of Ireland (NLI), it became possible to hazard an intelligent guess at the nature of the man’s political relationship with his wife. Equally, a wealth of atmospheric detail was gleaned from the Bureau of Military History (BMH) witness statements and from the Military Service Pensions Collection in the Military Archives of Ireland (MAI), as well as from the colourful memoirs of the likes of Barry, Deasy, Ó Ceallaigh, O’Malley and Ó Maoileóin. And the Papers of Florence O’Donoghue (NLI) and Seán MacEoin (UCDA), together with Pollard, Secret Societies, and Moody/Ó Broin, Documents, were found to be very helpful in tracing the lineage of Mulcahy’s attitude to Collins’ IRB.

A trawl of the impressive library of modern Irish history publications was undertaken additionally. Furthermore, some classic pieces from the disciplines of political science and governmental studies, along with the small, latter-day history corpus dealing with the emergence of Irish democracy, were the better studied in order to understand Mulcahy as a soldier-politician, and to compare and contrast the Irish civil–military question with similar post-imperial state formative processes which were ongoing throughout Europe at the time.

Of course, on occasions, such researches can generate more perspiration than inspiration. Consequently, I am very grateful to those people who went out of their way to be of assistance to me. In that category, during the early years, I would like to list the following: Risteard Mulcahy, Richard’s son, who courteously expedited my researches by allowing photocopying to happen; Garret Fitzgerald who dispassionately facilitated access to Defence files; Peter Young, proto-archivist of the MAI, whose enthusiasm was infectious; anti-Treatyites, like ‘Todd’ Andrews, Seán Dowling and Peadar O’Donnell, who responded candidly to my questions; Máire Tobin, daughter of Liam, as well as Pádraig Thornton, son of Frank, both of whom were happy to share their opinions and provide documentation; and last, but certainly not least, Prof. J.J. Lee, whose support and advice I was fortunate to benefit from during the period, 1982–87, while writing the Ph. D. thesis from which this book originates.

Then, of late, in terms of the archives and libraries visited, the following professionals deserve special mention: UCDA: Orna Somerville and her assistants, Kate, Meadhbh and Sarah; NLI: Avice-Claire McGovern and Saoirse Reynolds; NAI: Louise Kennedy; MAI: Noelle Grothier; Irish Christian Brothers Archive: Michelle Cooney and Karen Johnson; Irish Capuchin Archive: Brian Kirby; UCC archives: Mary Lombard; Cork City and County Archives: Brian McGee and Tim O’Connor; South Dublin Libraries: David Power; Cork County library: Kieran Ryan; Tipperary Local Studies and Archive: Jane Bulfin; Waterford City and County Archive: Joanne Rothwell; and the Postal Museum Archive, London: Barry Attoe.

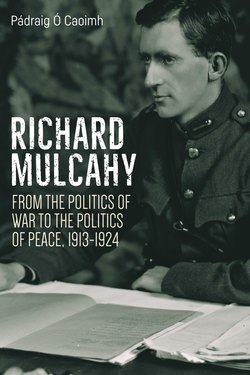

And, moreover, I would like to thank Risteard Mulcahy, Richard Mulcahy’s grandson, who so generously offered moral support and facilitated the digital photographing of images of his grandfather. Also, I am indebted to Conor Graham, who perceived merit in my project, and his hard-working staff at Irish Academic Press, especially Fiona Dunne, the managing editor.

Ach, i ndeireadh na dála, ba mhaith liom aitheantas áirithe a thabhairt do mo theaghlach, sé sin do mo bhean chéile, Assumpta, agus do mo bhuachaillí, J.P. agus Éamonn, mar gheall ar an dtacaíocht dhíograiseach a thugadar dom ón nóiméad a shocraigh mé filleadh ar an bpeann.

Pádraig Ó Caoimh

October 2019