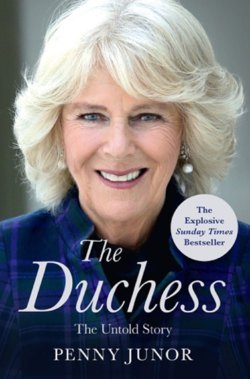

Читать книгу The Duchess: The Untold Story – the explosive biography, as seen in the Daily Mail - Penny Junor - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

The Foundation Years

Bruce and Rosalind were a golden couple who seemed to have everything: good looks, charm, class, money, healthy children and a happy marriage, one that did last an eternity. Bruce was a genial, cultured man who loved art and music as well as his horses. He was courteous, immaculately dressed, scrupulously polite, always smiling; a man to whom people immediately warmed. So was Rosalind. She was big-bosomed, big-hearted, generous and tactile. She too dressed smartly in skirts and suits, with bright red lipstick, but she was less conventional than she looked. She invariably had a small cigar in one hand, and liked her children’s friends to call her by her first name, which was unusual in the 1950s. She was a strong woman from a long line of strong women.

Rosalind could be sharp – she didn’t appreciate being called Ros – but she was very funny and famed for her throwaway lines. When a teenage Camilla and her friend, Priscilla, were dressed up to the nines, ready to hit the town of Brighton for the evening, she said, ‘My God, Camilla, you look just like Mandy Rice-Davies with spots!’ For all that, she was hugely caring. Every Wednesday for seventeen years she went to Chailey Heritage, a school for the disabled outside Lewes, where she worked as a volunteer with thalidomide children. She only stopped when the pain of her osteoporosis made it impossible to make the journey.

The house in East Sussex where they settled after Camilla’s birth, a seven-bedroom former rectory, called The Laines – initially they rented it – is not classically beautiful. But its position, nestling at the foot of the South Downs with not another building in sight, is hard to beat, and the garden that Rosalind created, like a series of rooms, is still beautiful. The main section was built in the eighteenth century in the local style of flint and red brick, with later additions; the ivy-clad house sits on a slight incline at the end of a gravel driveway, in complete seclusion, surrounded by five acres of garden, with fields belonging to the neighbouring farm beyond. It’s big but not grand, essentially a comfortable family home, with light, airy rooms, high ceilings and open fireplaces where log fires crackled in winter. Like all old houses with rattling windows – royal ones included – it could be very cold.

The kitchen did not play a part in family life, as it might do today. Tucked away in the servants’ wing behind a green baize door, it was small and dingy, as kitchens so often were at that time, even in the smartest houses, and was the domain of the cook. Rosalind didn’t cook. She preferred the growing and eating of food and left the cooking to Maria, the female half of a devoted Italian couple who were with the family for many years. Her husband waited at table. Another couple lived in a cottage at the end of the drive: David was an oddjob man-cum-gardener and chauffeur, and Christine was the cleaner and housekeeper.

It was a house for living in, for wonderful meals with friends, for children and dogs, not a status symbol – but it was filled with beautiful things, particularly paintings. Rosalind had a good eye and was a great homemaker, as her daughters are. She used warm, earthy colours and pretty fabrics. The furniture was a mix of old and new, of comfortable modern sofas and chairs and antique chests, desks, tables and mirrors; there were plenty of objets d’art scattered about, bits of silver, table lamps and framed photographs. Many of the better pieces were heirlooms, mostly from Rosalind’s side of the family. The dogs were Sealyham terriers.

Although they didn’t use the kitchen, food and drink played an important part in the family’s lives. They gathered round the dining-room table for noisy meals, with their framed ancestors looking down at them from the walls, and ate simple but delicious fare with vegetables fresh from the garden. It was the scene of many a lively dinner party too. Guests would afterwards repair to the drawing room, an elegant formal room, but when it was just the family they used a smaller sitting room, to which in the 1970s they added an orangery that Rosalind filled with plants. Or there was the library, with a club fender around the fireplace. Books were everywhere; Bruce’s study, where he sat for many hours reading and working, was lined with them.

Camilla’s bedroom was always a mess. It was above the drawing room, with a bathroom next door that she shared with Annabel, whose room was beyond. There were four bathrooms but none of them were en suite – few were in those days – although each bedroom had a washbasin. The house was often full. Friends and family came from all over to stay or spend weekends. They would come to attend events at Glyndebourne, the great opera house that was just a fifteen-minute drive away – the Christie family who ran it were good friends – or there was the Theatre Royal in Brighton, where shows were trialled before moving into the West End of London, and there was horse racing at Plumpton just along the road. Hunting friends would come for a day out with the Southdown and in the summer, the beach was no more than half an hour away.

Bruce and Rosalind were a sociable pair at a time when people living in the countryside enjoyed an active social round, before the breathalyser put an end to drink-driving, and while domestic staff were still present to make entertaining easy. It was a time when people dressed up for the theatre and changed into evening wear for dinner, when the ladies withdrew afterwards to powder their noses, leaving the men to talk, smoke cigars and pass the port. But although they lived in one of the biggest houses around, they were refreshingly modest – even after Bruce was appointed Deputy and then Vice Lord Lieutenant of East Sussex in the early 1970s. He also became an officer in the Queen’s Bodyguard (the Yeomen of the Guard), whose headquarters are at St James’s Palace. This elite group is the oldest British military corps still in existence, and has all sorts of arcane titles. Bruce was invited to join it in middle age, and when he retired at the age of seventy he had reached the rank of Clerk of the Cheque and Adjutant. It was a career, he joked, that involved dressing as if to fight the Battle of Waterloo – and one that Rosalind hadn’t been able to take too seriously. ‘Oh God, Bruce, do you have to?’ was her reaction. She may have been upper class to her bootstraps, but you would never have known it from her conversation or her lifestyle – and class was a word she abhorred. She never actually voted Labour, but she certainly flirted with the idea; she was a thoroughly egalitarian woman who took everybody at face value no matter what their background. There was never a hint of snobbishness or entitlement from any of them. Every year they opened their garden to the public, they held fundraising events and parties for the hunt and the pony club. All the children’s friends came to swim in the pool. Everyone was welcomed with the same warmth, and when Bruce left the village after Rosalind’s death, having lived there for forty-five years, locals had nothing but good words to say about them.

Camilla, Annabel and Mark could not have had more perfect childhoods, as they have all at various times said. These extraordinary parents filled the house with merriment, boosted rather than criticised them and made them feel valued, safe and loved. They encouraged them to be their own people, to seize life with both hands. To believe that the world was a good place with good people in it, that life was to be enjoyed – and that there would always be a welcome at home, no matter what. They were a tight-knit bunch who had each other’s backs covered and who respected one another.

Until her teens, Camilla’s life was about ponies. She rode them, she drew pictures of them, she read books about them and her bedroom was full of rosettes she had won at the local gymkhanas. Her favourite pony was a piebald called Bambino, who lived in a field at the bottom of the garden that they rented from the next-door farm. She loved it to bits and looked after it meticulously. Annabel rode but was never as keen as Camilla, while their mother didn’t ride, although her own father had been a master of foxhounds so she’d grown up around horses. Mark had no interest – he preferred elephants.

Camilla rode on the Downs, the range of rolling chalk hills that extend for about 260 square miles from the Itchen Valley in Hampshire to the white cliffs of Beachy Head, near Eastbourne. And covering the entire area is a network of public footpaths and bridleways. The main bridleway, the South Downs Way, is 100 miles long, but there are over 2,000 miles of other tracks. For a little girl in love with ponies, it could not have been more idyllic, and a childhood roaming free in such an expanse explains why Camilla is at her very happiest in the countryside.

Her great childhood friend, Priscilla Spencer, was also pony mad. Almost exactly the same age, Priscilla moved into a house across the fields when they were both eight, and went to the same school. For a while, she and her younger sister Judy, Camilla and Annabel all had riding lessons together with a fierce, ex-military man called Mr Stuckle. He took them up onto the Downs and bellowed at them until Annabel refused point blank to go again. After that they went riding by themselves, day after day. Often they’d be gone all day, riding for miles, flying over the wooden jumps known as tiger traps and dodging defence installations left over from the war. They took sandwiches in little leather boxes attached to their saddles. And sometimes, they would sleep overnight on the Downs, out in the open. This was long before mobile phones. Everyone wanted a mother who was as easy-going and relaxed as Rosalind.

The children never had nannies. Rosalind was a full-time, hands-on mother. Sometimes David in the cottage might ferry them to school but it was usually Rosalind, and she’d be there for the plays and concerts, the fetes, the fairs. On summer afternoons after school, she would take them down to the beach at Hove for a swim in the sea – something Camilla loves to this day. But most of the time she just let them do their own thing. She was strict about manners and hot on discipline – she would get furious with Mark for trashing her lawn with his go-cart – but she gave them the freedom to fly and in their different ways, they did. Bruce was never the disciplinarian in the family, and her mother would have said he let Camilla get away with murder.

Their friends loved coming to stay at The Laines, and it was as much to see Rosalind and Bruce as it was to be with them. As Priscilla says, ‘Sometimes you come across somebody who really is exceptional and Rosalind was that person. She was very like Camilla. A bit sharper of tongue but funny – the most amusing person you’d ever, ever meet. I absolutely adored her. And Bruce was the best looking man you’ve ever looked at in your life, urbane and charming.’

One very special feature of The Laines was the garden. It was Rosalind’s domain and her passion. With the help of well-known landscape gardener Lanning Roper, she created formal lawns, made rose gardens, planted hedging, shrubs, flowers and specimen trees, all of which are now fully mature. Outside the kitchen she put in a fig which she and Bruce brought back from the Garden of Gethsemane, in Jerusalem, and at the bottom of the garden she planted an oak sapling that they bought on the 900th anniversary of the Battle of Hastings. It was said to have come from the very oak tree in which King Harold’s mistress, Edith the Fair, sat to watch the battle in which he was slain. And in the walled garden she grew vegetables, and espaliered fruit trees along the walls.

Camilla did eventually inherit her mother’s love of gardening but growing up, if she wasn’t doing something horsey, she would be lounging around the swimming pool with her friends. Or she would be at school.