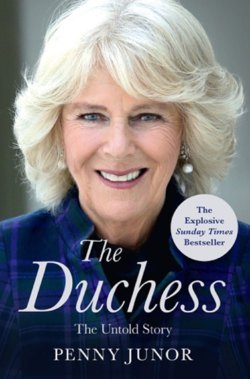

Читать книгу The Duchess: The Untold Story – the explosive biography, as seen in the Daily Mail - Penny Junor - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление6

The Stuffed Stoat

At the age of five, Camilla went to Dumbrells, a little village school in Ditchling, about three miles from her home. The pupils – the school was attended by both girls and boys – were housed in three classrooms and there was a dairy farm next door. The children either loved it or loathed it, sank or swam – and the difference was almost entirely down to whether the headmistress, a terrifying figure called Miss Knowles, rated them or not. She liked quick-witted children and if their intelligence wasn’t immediately evident, she had no interest in finding the key to unlock their potential. The result was swingeing favouritism. To her favourites she was the most extraordinary, exciting and inspirational teacher, who gave the lucky ones a passable education, a zest for the outdoors and a moral code for life. Camilla was one of those lucky ones, and her six years at Dumbrells were some of the happiest of her life.

The school was named after the three sisters who founded it 1882, the three Misses Dumbrell – May, Edith and Mary. Having fallen on hard times, with their widowed mother, they brought in a tenant farmer to run their farm and turned their home into North End House Home School, a boarding establishment for young children whose parents were in India. By the time Camilla arrived in 1952, the name had changed, there were no boarders, two ugly prefab wooden classrooms had been added, and the only Miss Dumbrell left was the very elderly Miss Mary, a tiny figure dressed in a long grey gown and mittens, out of which her tiny fingers peeped. Miss Knowles was in her fifties; she had been a pupil at the school, returned as an assistant teacher in 1924 and was there until it closed down in 1982. It is now a private house again. The front drive has been rerouted and an estate of sheltered housing has encroached on much of the garden that the children used to play in, but many original features remain – though not, alas, the alarming stuffed stoat in a glass case that used to greet the children as they came through the front door each morning. It appeared to be gazing in terror at a stuffed bat on the other wall.

French was taught from an early age, and at lunchtime one of the three long tables in the dining room – to which the children were summoned by a loud gong – was a ‘French’ table. Everyone who sat at it was expected to speak French to the teachers who presided. Translating spotted dick and jam roly-poly, two favourites, into French was quite a challenge, and during Camilla’s time the convention was abandoned. Lunch began and ended with the saying of grace. There was always a choice of two main courses with vegetables and two puddings – one a milk pudding, the other baked – but it was Hobson’s choice. To make sure there was enough of everything to go round, each child had to have something different from his or her neighbour, so if you hated rissoles or tapioca the clever thing was to sit next to someone who loved them. The food was generally delicious, and all freshly cooked – most of the vegetables came from the garden. No one was allowed to start until they had all had been served, nor finish until the teachers had finished. And anyone who didn’t finish their food had it taken into the Big Schoolroom, where they had to eat it later in front of everyone under the eagle eye of Miss Knowles. Everyone had to use a knife and fork and hold them properly with their first finger on the shaft – not like a pen. There was no speaking or drinking water with one’s mouth full, and no shouting. And neighbours had to look after each other and pass them what they needed. At the end, everyone stood while grace was said again.

Miss Kempton, the cook, was an eccentric woman with a harelip. The children were scared of her and because of the lip, found her very difficult to understand. For some reason Camilla and Priscilla could make out what she was saying better than anyone else, so every day Miss Knowles sent the two of them off to the kitchen, missing the last lesson of the morning, to help Miss Kempton prepare the lunch. Across the corridor was a little room, not much bigger than a cubbyhole, which permanently smelt of sour milk. It was where the maid, Sarah, poured the milk that was obligatory at break time. It came directly from the farm, a stone’s throw away, which was run by a jolly red-faced fellow called Mr Holman. He had a celebrated herd of Guernsey cows, so the milk was rich and creamy, even though most of the children hated it. The farm had not been mechanised until just before the war. All the cows had been milked by hand, and a big white carthorse called Blossom used to pull the plough. They now had a tractor, but Blossom lived on and the children loved her. They would watch her from one of the windows in the Big Schoolroom that looked out over the farmyard.

The Big Schoolroom was Miss Knowles’ domain. There, all the children, a great mixture of ages, sat at old-fashioned wooden desks, each one with a little china ink pot, while Miss Knowles repeatedly drummed into them the finer points of English grammar, throwing pencils and books at anyone bold enough to misbehave. The room doubled up as a gym, so there were wall bars behind her desk, ropes coiled up near the ceiling and fittings for parallel bars on the walls; and it was where morning prayers were held at the start of the day. The afternoons were the best part of every day. Miss Knowles would read a story, everyone sitting in rapt attention as she read Ivanhoe, Kenilworth, Barnaby Rudge and Treasure Island – classics by Sir Walter Scott, Charles Dickens and Robert Louis Stevenson, all unabridged – which would be impenetrable for most of today’s eight- and nine-year-olds. She read unemotionally but accurately, bringing the books to life by richly impersonating all the characters, while narrative poems also formed part of her repertoire; Hiawatha was one of her favourites. In summer, she would sometimes read to the children in the garden. When the soft fruit was ripe, they would sit cross-legged on blankets on the lawn, topping and tailing gooseberries and blackcurrants while Miss Knowles read the story.

Miss Knowles had a ruddy face that had never seen make-up, big blue eyes and wavy chestnut hair tied into an untidy bun at the nape of her neck. Day in day out, she was in the same clothes: a navy V-necked frock with a cream blouse underneath, and when it was cold, a navy jacket over the top. The outfit was finished off with black stockings and plain black court shoes, which made a very distinctive clacking sound in the corridors that ensured she never arrived unannounced. Josephine Ferguson, a pupil at the school in the 1940s, wrote about it in her book The Stuffed Stoat, saying Miss Knowles had once explained that an aunt had left her twenty-nine pairs of stockings and umpteen dark blue frocks and that being hard up, she had felt obliged to wear them to save money. History doesn’t relate whether she was still working her way through the same twenty-nine pairs of stockings in the 1950s, but her daily outfit was identical.

For her pupils, though, there was no uniform. Most of the girls, Camilla included, wore dresses; and she had long white socks that miraculously always stayed up, while other people’s slid down to their ankles.

What everyone loved best of all were nature walks, when the children roamed the countryside collecting as many different wild flowers as possible, putting them into jam-jars for Miss Knowles to identify before they were pressed and pasted into books. There was a prize at the end of the term for the child with the best collection. Sometimes the walks simply crossed the farmland at the back, sometimes they took the children further afield – walking along the road in a crocodile holding hands, two by two – to the orchid woods or the Downs.

There was very little competition in the school – and some would say very little learning. Sports day was low-key and showing off in any way was forbidden. There was a nativity play in the Christmas term, in which Camilla and Priscilla once sang ‘We Three Kings of Orient Are’, and every year a big Christmas tree was installed in the schoolroom, decorated with real candles that were lit. Today’s health and safety inspectors would have had a fit. But the big event of the year was the summer play in which all the bigger children had a part, and which they rehearsed for weeks.

Miss Knowles was a stickler for manners, and not just at the lunch table. She taught the children how to introduce people to one another correctly, and before the summer play everyone had to introduce their parents to those of their friends if they hadn’t yet met. It was a given that they should look people in the eye and shake hands politely, and should be just as polite to Sarah, the maid, and Cherryman, the gardener, as they were to other people’s parents.

Miss Mary died in 1962, and twenty years later Miss Knowles retired and went to live in a cottage in a nearby village. Josephine Ferguson summed up Dumbrells in the following terms:

unfortunately for posterity, there will never again be a school like it, and there will probably never again be such remarkable and dedicated characters as the Dumbrell sisters and Miss Knowles, who devoted their lives to teaching just a few of us, out of four generations, to have not only an erudite and resourceful outlook on life, but a compassionate manner towards our fellow beings, at the same time saving us from being priggish goody-goodies by their delightful sense of humour, which they passed on to us. They were unique women, but would never have thought themselves so.

By the time the school closed Camilla was married and living in Wiltshire, but she often came back to Plumpton to see her parents and would occasionally go and visit her old teacher. It was an indication of just how much she’d enjoyed Dumbrells and how much she owed the school for her happy start in life. Miss Knowles had followed her progress in the meantime, as she had no doubt followed that of all her favourite pupils. When one of Camilla’s contemporaries was picking up a nephew from the school in 1973, Miss Knowles excitedly showed her a copy of the Tatler with photographs of Princess Anne’s wedding to Mark Phillips. There in the line-up was Camilla.