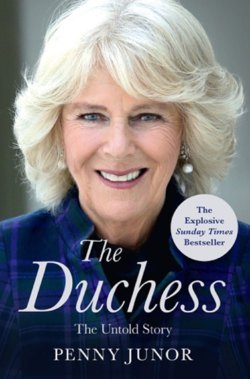

Читать книгу The Duchess: The Untold Story – the explosive biography, as seen in the Daily Mail - Penny Junor - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Debs’ Delight

ОглавлениеThe Prince of Wales first met and fell in love with Camilla Shand in the summer of 1971. They were introduced by a mutual friend, the glamorous Chilean historian Lucia Santa Cruz. Lucia and Charles had met in 1968 shortly after he began as an undergraduate at Trinity College, Cambridge. Lucia was not a student; she already had a degree from Oxford and was a few years older than Charles. She was working as a research assistant to Lord Butler, the distinguished former Conservative minister who was then Master of Trinity, and was writing his memoirs, The Art of the Possible. Rab and Mollie Butler were good friends of Lucia’s parents, the Chilean ambassador and his wife, and they invited her to dinner at the Master’s lodge to meet the Prince, thinking they might enjoy one another’s company. They did; they became lifelong friends – but never in a romantic way. Lucia has repeatedly been credited with being the Prince’s first lover but this could not be further from the truth. She already had a serious boyfriend, the man who is now her husband, Juan Luis Ossa Bulnes, and they have children and grandchildren together in Chile. Charles is their eldest son’s godfather.

Lucia’s parents went back to Chile in November 1970, after Salvador Allende became president, bringing in a Marxist government and bringing an end to her father’s time at the embassy. It was a difficult period for her but because of the political uncertainty, she stayed on in London to fend for herself, living at Stack House, a block of flats in Ebury Street, Belgravia. She was on the first floor and her neighbour in the flat below was Camilla Shand, then sharing with her friend the Hon. Virginia Carington, whose father was the Conservative politician Lord Carrington.

Lucia and Camilla already knew one another socially – they moved in the same circles – but as neighbours they became good friends and Camilla took Lucia under her wing. They were in and out of each other’s flats every day, borrowing clothes, going to the same parties and dances – and at weekends Camilla would take Lucia down to her parents’ house in the East Sussex countryside. Lucia spent that first Christmas with the family and woke up on Christmas Day, as all the young did, to a pillowcase full of presents at the end of her bed, delivered by Father Christmas. And downstairs there were more presents. Every time she went, she was made to feel at home; they were always welcoming and generous to friends, and with her own parents so far away it meant a lot. One of her most treasured memories was asking Camilla’s father, Bruce, about the Second World War, whereupon he described to her some of the experiences that led to his capture by the Germans. He went on to write a book about it, Previous Engagements, published in 1990, but at the time his family had never heard him speak about it.

Camilla was dating Andrew Parker Bowles, and Lucia inevitably knew all about him. They had first met in March 1965 at her ‘coming out’ party as a debutante – a cocktail party for 150 people given by her mother at Searcy’s, a smart venue behind Harrods in Knightsbridge. He was twenty-five and a rather beautiful officer in the Household Cavalry; she was seventeen but remarkably self-assured. She was good company, well read and intelligent – but neither university nor serious work had ever been in her game plan. She wanted nothing more than to be an upper-class country wife with children and horses and an enjoyable social life.

Being a debutante is a custom long gone – some would say mercifully – but the upper classes once used to launch their seventeen-year-old daughters into society in the hope of finding them an eligible husband. For the season, a year, they partied seamlessly night after night, weekend after weekend. Each party was a concentration of privilege and titles, all chronicled in two glossy magazines, Tatler and Queen. The highlight, and the glitziest of the lot, was Queen Charlotte’s Ball, a huge charity event held at the Grosvenor House Hotel on Park Lane, a confetti of conspicuous wealth. And if nothing else, that season ensured these young women would have connections and invitations for life. The men were known as ‘debs’ delights’ and while the girls could only do one season, the boys – so long as they were bachelors – could carry on reaping the benefits of other people’s hospitality year after year. All they needed to ensure the invitations kept coming was access to the right kit – namely a white tie – and an ability to charm the mothers.

The whole thing dated back to 1780 when King George III held a ball in honour of his wife, Queen Charlotte, to celebrate her birthday and to raise money for the maternity hospital which bears her name; the centrepiece was a large cake. It became an annual event at which several hundred nubile girls were formally presented at court – and it was held at Buckingham Palace until 1958, when the Duke of Edinburgh pointed out that the whole thing was ‘bloody daft’ and his sister-in-law, Princess Margaret, said that ‘every tart in London was getting in’. By the time Camilla came out, Queen Charlotte’s Ball was held at the Grosvenor House, and the ‘Queen’ to which the girls were presented was nothing more regal than a giant cake.

Andrew was a debs’ delight par excellence. One of his partners in crime was Nic Paravicini, a fellow officer and polo-playing friend who later became his brother-in-law and business partner, being married to Andrew’s sister, Mary Ann. The couple subsequently divorced, but Andrew and Nic remain good friends. Footloose and fancy-free in those early days, and based with their regiment at Knightsbridge Barracks, they were geographically at the centre of all the action, and were two of a kind. Andrew was charming, smooth talking and debonair, and thanks to his Army training and riding he was slim and fit in every sense of the word. All the women were after him, some of them married – and he knew it, and reaped the benefits. He was one of the most attractive young men on the deb circuit, and a good catch too: he has noble blood coursing through him and connections with royalty going back generations. His parents, particularly his father, Derek, were close friends of the Queen Mother and in 1953, at the age of thirteen, he was a page boy at Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation. Camilla may have had a boyfriend at the time of her coming out party – she was hugely popular with boys from an early age – but she noticed Andrew that night, and he her.

Soon afterwards he disappeared to the other side of the world to be aide-de-camp to the Governor-General of New Zealand, Sir Bernard Fergusson. They didn’t meet again until 1966, at a dance in Scotland, shortly after his return. She was looking very pretty, as usual, and the centre of attention, as usual, so he went over to her and simply said, ‘Let’s dance.’ They danced, and she fell in love. It was the beginning of a long and torturous romance – torturous because she became a puppet on a string. He was hugely fond of her, and she was nominally his girlfriend – she spent innumerable weekends with him at his parents’ house near Newbury with all his siblings and their friends, but he couldn’t resist other women, and what was particularly hurtful was that many of them were her friends.

Occasionally she retaliated. One night she spotted Andrew’s car parked outside the flat of one of her best friends, so she wrote a rude message in lipstick on the windscreen and let all the air out of his tyres. But curiously, for such a strong, confident and intelligent woman, she put up with his behaviour – possibly because as well as being strong and confident, she has also always been determined and stubborn, and once she had made her mind up that she wanted to marry Andrew, nothing was going to stop her.

Lucia decided her friend needed to meet the Prince of Wales, who had no satisfactory girlfriend, and so she contrived to introduce them to one another. It happened on an evening in 1971 when Lucia and the Prince had arranged to go out together; she told him to come early, she had ‘just the girl’ for him and described Camilla as having ‘enormous sympathy, warmth and natural character’. Charles had recently been in Japan and had brought a present for Lucia, a little box, and knowing he was to meet her friend Camilla, he’d brought a gift for her too. As Lucia made the introductions she joked, ‘Now you two be very careful, you’ve got genetic antecedents’ – referring to Alice Keppel, Camilla’s great-grandmother, who had famously been a long-term mistress of King Edward VII, Charles’s great-great-grandfather. ‘Careful, CAREFUL!’

In Lucia’s first-floor flat that evening, there was an immediate attraction between the two of them and an instant rapport; Charles loved that she smiled with her eyes as well as her mouth, and laughed at the same silly things he did. He also liked that she was so natural and easy and friendly, not in any way overawed by him, not fawning or sycophantic. He was very taken with her and after that first meeting he began ringing her up. Then they met and he continued to feel easy in her company. But it was a busy time for him and he was seldom at home.

Charles was young and shy, only twenty-two, and in the midst of intensive military training. He had just qualified as a jet pilot with the Royal Air Force, and was about to embark on a career in the Royal Navy. He loved flying – he had taken it up at university and had a natural aptitude for it – but the Navy was a family tradition, and boats were deemed safer for the heir to the throne than jets, so that was where he was ultimately headed. He passed out of RAF College at Cranwell having earned his wings in just under five months – rather than the normal twelve – with the highest commendation, and having won membership of the exclusive Ten Ton Club by flying at more than 1,000 mph. He was in the back seat of a Phantom, scrambled from RAF Leuchars in Fife on a training exercise; they climbed to 35,000 feet in two minutes, almost vertically, launched a mock attack on an enemy aircraft, and flew twice over Balmoral, the Royal Family’s home in the Highlands of Scotland, at 400 feet, causing seven locals to phone the police in protest, before going supersonic over the North Sea. He had also scared himself half to death by jumping out of an aircraft at 12,000 feet with a parachute that wrapped itself round his feet. Fortunately he had the presence of mind to disentangle himself and descended harmlessly into the sea at Studland Bay in Dorset. The press was full of praise for his derring-do and started billing him as Action Man. At that time, the country’s most eligible bachelor could do no wrong.

After the freedom of flying, Dartmouth Royal Naval College, where he started in September 1971, was like going back to boarding school all over again, and he hated it. He did an intensive ‘fast stream’ six-week course, again half the length of the normal course. Yet when he graduated, top in navigation and seamanship, neither of his parents came to the ceremony. The only member of the family who showed was his beloved great-uncle, Louis, Earl Mountbatten of Burma, the man who had been Supreme Commander in South East Asia during the Second World War, the last Viceroy and first Governor-General of India, First Sea Lord and finally Chief of the Defence Staff. Mountbatten was the man Charles called his honorary grandfather. He had been devoted to him since he was a small child. Realising at the last minute that no one else would be there to watch the graduation, Mountbatten flew down to Devon from his home in Hampshire in a helicopter for the occasion. Weeks later, Charles flew out to Gibraltar to join his first ship, the destroyer HMS Norfolk.

Charles was with Norfolk for nine months, some of which was spent on shore-based training courses in Portsmouth. Mountbatten’s home, Broadlands, was less than half an hour’s drive away and so Charles was a frequent visitor, and this was the time when the two men became especially close. Mountbatten had realised some years earlier that Charles was adrift; his relationship with his parents left a lot to be desired and he needed confidence and guidance in his future role. It was Mountbatten who told him, in regard to women, that it was important ‘in a case like yours, the man should sow his wild oats and have as many affairs as he can before settling down, but for a wife he should choose a suitable attractive and sweet-charactered girl before she has met anyone else she might fall for … I think it is disturbing for women to have experiences if they have to remain on a pedestal after marriage.’

In the late autumn of 1972, Andrew Parker Bowles was away with his regiment and Charles was on dry land for long enough to hook up with Camilla. They saw one another whenever the opportunity presented itself. This was quite often at Smith’s Lawn, the Guards Polo Club in Windsor Great Park, where both Charles and Andrew played, for a time in the same team. Camilla had been a regular sight at polo matches for years, watching Andrew and his friends play – and the father of one of her friends was chairman of the club. So she could go and watch Charles play without arousing particular attention. The Prince had not taken up polo until the age of sixteen, but he became a fanatical player, raising vast sums of money for charity in the process. The Duke of Edinburgh was president of the club and a very able player, as was Lord Mountbatten, who had written the definitive book on the sport. Both had been very keen that Charles should play.

By this time, Andrew was serving in Northern Ireland in the aftermath of the Bloody Sunday massacre – a seminal event in which the British army, at the height of the Troubles, fired on unarmed civilians engaged in a peaceful protest and killed twenty-six of them. After Ulster he was posted to Cyprus, so for most of 1972, Charles had Camilla to himself, and the two of them spent very happy times together, quite often at Broadlands, which was a safe place away from the prying eyes of the press. But while Mountbatten was only too happy to play host to the pair, he made it abundantly clear that this relationship could never go anywhere in the long term. Camilla was not sufficiently aristocratic to be the Prince’s wife, and she was not a virgin, which was a prerequisite.

The Prince was falling ever more deeply in love, and although far too reticent to say anything to Camilla was beginning to feel that, despite Mountbatten’s admonitions, he might have found someone he could share his life with. The only cloud on his horizon was that in the New Year he was due to leave for the Caribbean in the frigate HMS Minerva, which would take him away for at least eight months. He joined the ship three weeks before Christmas – and invited Mountbatten and Camilla both for a tour of inspection and lunch.

They were at Broadlands the weekend before he sailed, but he said nothing to indicate his strength of feeling, which was maybe just as well for his pride because Camilla may not have known how to respond. She was hugely fond of Charles, flattered by his attention, and they had had a very good time together, but she was in love with Andrew. To her fury, Andrew was also seeing Princess Anne, Charles’s feisty younger sister. He had never been known to date just one girl at a time, but he seemed to be unusually smitten, and rumour had it that so was Anne. During their time together he was even invited by the Queen to join the family at Windsor Castle for Ascot week. So there was an element of tit-for-tat in Camilla’s fling with Charles. She also enjoyed the historical connections – their great-grandparents’ affair – which had always intrigued her. But her principal motivation was to have some excitement and make Andrew jealous. She knew it would never go anywhere, could never go anywhere.

Might she have felt differently if Charles had told her how special she was, how beautiful and funny, how warm, how sexy? If he had told her that he loved her above all things, that he couldn’t live without her and that he would find some way of marrying her? It is impossible to know; not even those who know her best are convinced she would have said yes to him. Andrew was never very nice to her, never made her feel special, but she was stubbornly determined to marry him. His playing around had hurt her to the core, but her heart was still set on him. The fact that every other woman in London fancied him only made him more attractive to her. She adored him, and she had been dating him through thick and thin for seven years. She wanted to be Mrs Parker Bowles, wife of her handsome cavalry officer, not Princess of Wales, not Queen.

Andrew knew that his relationship with Princess Anne could never end in marriage. However much in love they may have been, he was a Roman Catholic and the 1701 Act of Succession – not changed until 2011 – expressly forbade an heir to the throne to marry a Roman Catholic. Princess Anne at that time was fourth in line and was not about to cause a constitutional crisis. She turned her attentions to a younger model, to Mark Phillips, a captain in the Queen’s Dragoon Guards, and a three-day eventer who had just won a gold medal at the Montreal Olympics in 1972. Anne was herself a talented three-day eventer – she had won a gold medal at the European Eventing Championships the year before and been voted BBC Sports Personality of the Year in 1971 – and they had met on the eventing circuit. Theirs was a marriage made in the saddle, though apart from horses they had little common ground.

For a moment, Andrew must have thought he was about to lose both women. And so in March 1973, when Charles was thousands of miles away in the West Indies, Andrew asked Camilla to marry him and she agreed. She wrote to Charles herself to tell him. It broke his heart. He fired off anguished letters to his nearest and dearest. He has always been a prolific letter-writer. It seemed to him particularly cruel, he wrote in one letter, that after ‘such a blissful, peaceful and mutually happy relationship’ fate had decreed that it should last a mere six months. He now had ‘no one’ to go back to in England. ‘I suppose the feeling of emptiness will pass eventually.’ He did have one last-ditch attempt to get Camilla to change her mind, however. He wrote to her the week before the wedding asking her not to marry Andrew. Nevertheless, the wedding went ahead. Her mother, Rosalind, was not entirely happy about it – she didn’t think Andrew treated her daughter very well – but Camilla was determined. She foolishly believed that leopards can change their spots.