Читать книгу The Traprock Landscapes of New England - Peter M. LeTourneau - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

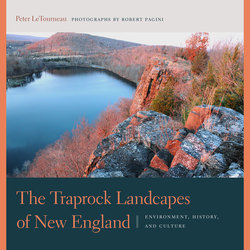

ОглавлениеAccording to noted landscape historian John Brinckerhoff Jackson, the rich soils and mild climate of the Connecticut Valley offered the early English settlers their “first reassuring glimpse of the rich New World they had dreamt of, but had failed to find on the shores of Massachusetts Bay.” View of the Connecticut River from Mount Holyoke, looking north.

2

Rising in Shapes of Endless Variety

GEOGRAPHY OF THE TRAPROCK HIGHLANDS

The whole of this magnificent picture, including in its vast extent, cultivated plains and rugged mountains, rivers, towns, and villages, is encircled by a distant outline of blue mountains, rising in shapes of endless variety.

Benjamin Silliman, Remarks Made on a Short Tour between Hartford and Quebec in the Autumn of 1819 (1820)

With its long and storied cultural history, interesting rocks and minerals, fascinating fossils, rich soils, and distinctive landforms, the Connecticut Valley is a region that holds special meaning for geographers, geologists, paleontologists, farmers, writers, artists, historians, landscape tourists, outdoor enthusiasts, and, surprisingly, even cigar aficionados. A locus for important cultural, scientific, technological, academic, agricultural, and economic developments in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Connecticut Valley continues today as a vital center of technology, education, and finance.

For geographers, the Connecticut Valley is the elongate lowland in central Connecticut and Massachusetts. Comprising the most prominent physiographic feature in southern New England, the Connecticut Valley, with its chain of traprock hills, is clearly visible in satellite imagery. On the ground, the Connecticut Valley is recognized not only by its lowland topography, but also by its distinctive geology. The main part of the Connecticut Valley measures about 85 miles long from Northampton to New Haven and just over 20 miles from east to west at its widest point north of Hartford. The historic Deerfield Valley is a small northern extension of the main Connecticut Valley measuring about 5 miles wide and 15 miles in length from Greenfield to Amherst, Massachusetts.

The terms Connecticut Valley and Connecticut River Valley refer to separate, but partly overlapping, geographic features, a fact that has caused considerable consternation among geographers at least since the late 1800s, when Harvard’s William Morris Davis outlined the characteristics of the two distinct regions. Even more vexing for geographers is the fact that, although the Connecticut River appears comfortably ensconced in the Connecticut Valley lowland, it nonetheless makes an abrupt easterly exit at Middletown by cutting through more resistant Paleozoic-age metamorphic and igneous rocks of the Eastern Highlands on its way to Long Island Sound. Thus, the name Connecticut River Valley refers to the lowlands surrounding the largest river in New England, a watercourse that passes through the northern part of the Connecticut Valley on its 410-mile journey from the Connecticut Lakes in northern New Hampshire to Long Island Sound at Old Saybrook, Connecticut.

Viewed from Chauncey Peak, the Metacomet Mountains form a great wall from Mount Higby near Middletown (left), to Beseck Mountain, Middlefield (center), and Pistapaug Mountain, Durham (right). These formidable landforms exerted a strong influence on patterns of settlement and travel corridors. George Washington passed through the rugged gap between Pistapaug and Fowler Mountains when he traveled from Wallingford to Durham, Connecticut, first in 1775 to gather supplies for his soldiers, and again on his presidential tour of 1789. Historical monuments in East Wallingford and Durham, Connecticut mark the route.

For farmers and students of New England history, the Connecticut Valley is synonymous with rich soils possessing a favorable mixture of sand, silt, and clay, high organic content, and good water-holding capacity. From the Woodland Period through the early years of European contact, the alluvial terraces bordering the Connecticut River and its major tributaries supported substantial Native American villages with a nutritious triumvirate of corn, beans, and squash, supplemented by fish and game from adjacent waters and forests. The Dutch explorer and trader Adriaen Block was the first European to explore the Connecticut Valley by mapping the Red Hills (Rodenbergh) region near New Haven and sailing up what he called the Versche, or “Fresh,” River as far as the Enfield rapids in 1614. Attracted by the abundance of beaver, muskrat, and other furs, Dutch traders established Huys van Hoop (the House of Hope), a profitable but short-lived outpost at present-day Hartford, to process pelts arriving from the interior hinterlands. More interested in furs than farming, and facing the inevitable decline of an economy based on the reproductive rates of small mammals, as well as rapidly increasing numbers of English settlers who began arriving in the early 1630s, the Dutch began ceding their interest in the Connecticut Valley by the mid-1600s.

Lured to the Connecticut Valley by reports of arable lands bordering the Connecticut River and hopes of cutting into the Dutch fur trade, the English established the earliest permanent settlements in the region at Windsor (1633), Wethersfield (1634), Agawam (1635), Hartford (1635–37), and Springfield (1636), followed by Farmington (1640), Longmeadow (1644), Middletown (1651), Northampton (1653), and Deerfield (1673). According to the noted landscape historian John Brinckerhoff Jackson, the productive soils, ample precipitation, and long growing season of the Connecticut Valley provided the English with “the first reassuring glimpse of the rich New World they had dreamt of, but had failed to find on the shores of Massachusetts Bay.”1

Setting the benchmark for agricultural productivity in New England, the Connecticut River “intervales” were widely sown with wheat and rye in the early years. In his exhaustive history of New England farming, A Long Deep Furrow (1982), Howard Russell rightly called the Connecticut Valley “the continent’s first wheat belt … the … breadbasket of New England: first the area around Hartford, then the middle section” (that is, from Northampton to Springfield). Production of wheat on the Connecticut River intervales was so successful that the Pynchon family, among the first settlers of Springfield, shipped around 1,500 to 2,000 bushels of the valuable grain to Boston each year, beginning in the late 1660s. Wheat from the northern Connecticut Valley also relieved a severe famine in Virginia in 1674. After a series of wheat rust blights, the farmers realized that the warm humid lowlands were more favorable for corn and hay, crops that came to dominate the central and northern Connecticut Valley.

The Connecticut Valley and the Connecticut River Valley are separate, but overlapping, geographic regions. After flowing through the Connecticut Valley for more than seventy miles, the Connecticut River exits the central lowland at Middletown, Connecticut.

Today, with sprawling housing developments and commercial strips dominating the landscape, it is hard to picture the vast amount of land under cultivation by the early nineteenth century. Referring to the Connecticut Valley in 1810, the New England geographers Jedidiah Morse and Elijah Parish declared: “The most important production of New England is grass. This not only adorns the face of the country, with a beauty unrivaled in the new world, but also furnishes more wealth and property to its inhabitants, than any other kind of vegetation. A farm of two hundred acres of the best grazing land, is worth, to the occupier, as much as a farm of three hundred acres of the best tillage land.”

Cresting a traprock ridge near Rocky Hill south of Hartford in 1833, British travel writer Edward T. Coke was impressed by the “magnificent view of … the light yellow corn fields covering the whole extent of the valley to a range of forest covered hills 20 miles distant.” Nearby Wethersfield, one of the oldest of the “river towns,” produced such prodigious crops of red onions in the sandy alluvial soil that travelers in the early 1800s noted that they could detect the pungent vegetable aroma far outside the village bounds.

The agricultural success of the river towns of the Connecticut Valley was soon joined by remarkable progress in craftsmanship and early manufacturing, the establishment of important academic and political institutions, as well as the founding of vibrant centers of national and international trade and commerce in New Haven, Hartford, and Springfield. By the early 1800s, the Connecticut Valley was firmly established as the model of American productivity, wealth, and ingenuity—factors, along with the scenic volcanic landscapes, that would elevate the region to national prominence, and make it one of the foremost destinations for landscape tourism into the early twentieth century.

The “river towns” of the Connecticut Valley, including Wethersfield (1634), are among the earliest permanent English settlements in New England. One of the oldest gravestones in Connecticut, dated 1648, belongs to Leonard Chester, an original settler of the town. He was allegedly lost for several days in the traprock hills, where he was beset by snakes and a fiery dragon, ordeals that gave rise to the geographic name Mount Lamentation. Image: author.

For cigar aficionados and agricultural historians, the Connecticut Valley is inseparable from fine shade-grown and broadleaf tobacco. Once noted for exceptionally high yields of hay and grain, by the late 1800s high-quality tobacco, mainly used for cigar wrappers, became the hallmark of Connecticut Valley agriculture in the region from Deerfield to Hartford. To simulate the very warm, humid, and cloudy climate of exotic tropical locations like Sumatra, Cuba, or Honduras, Connecticut Valley growers adopted the unique method of growing tobacco under large fabric enclosures. The tobacco “tents” also protected the large, but easily damaged, leaves from drying winds, harsh sunlight, and the deleterious effects of frequent summer thunderstorms. Long a premier variety, both shade-grown Connecticut Valley tobacco, and carefully tended sun-grown broadleaf, continue to command high prices as the preferred wrapper for the finest cigars. Although many tobacco fields were lost to housing developments, office parks, and commercial strips in the latter half of the twentieth century, the cultivation of tobacco remains an important part of the northern Connecticut Valley economy and an agricultural practice of historical significance.

The fertile alluvial terraces, or “intervales,” bordering the Connecticut River fostered some of the earliest permanent settlements in southern New England. View from Mount Holyoke.

While hay, corn, and tobacco reigned supreme in the northern Connecticut Valley, fruit orchards and dairy farms came to dominate the region south of Hartford. There, broad, streamlined glacial hills called drumlins proved ideal for apples and other native fruits because of their well-drained soils, favorable solar exposure, and a reduced chance of damaging late frosts in comparison to the colder surrounding valleys. Beginning in the 1700s, many family-owned orchards were established on the higher terrain adjacent to the traprock ridges, including Lyman Orchards in Middlefield (1741); Norton Brothers (1750s) and Drazen (early 1800s), both in Cheshire; Rogers in Southington (1809); Bishop’s (1871) in Guilford and near Totoket Ridge in North Branford; Blue Hills Orchards (1904) on the northern flank of Sleeping Giant ridge in Wallingford; and High Hill Orchards (early 1900s) in East Meriden near Beseck Mountain.

Similarly, dairy farmers found the well-drained drumlin hills better for grazing cows and growing hay than either the marshy alluvial lowlands or the stony traprock ridges. Today, only a few working dairy farms remain, but through the early twentieth century dozens of milk producers prospered on the glacial hills of the central and southern Connecticut Valley.

Tobacco has been a vital part of the agricultural history and culture of the Connecticut Valley since the 1700s. Early mid-twentieth-century cigar box with illustrations based on paintings by the renowned nineteenth-century artist George H. Durrie of New Haven. Inside cover: West Rock and Westville.

Side panel: Judge’s Cave on West Rock. Images: author’s collection.

Because of the difficulties presented by their challenging terrain, the traprock hills did not participate in the early agricultural productivity of the alluvial intervales or the glacial drumlins and remained marginal hinterlands of limited value. The steep slopes and thin, stony soils of the traprock highlands allowed only marginal grazing, and the dry montane forests were extremely slow to recover from cutting. Echoing the general opinion about the traprock highlands in their 1704 report to the Connecticut Colony, surveyors Thomas Hart and Caleb Stanley found Mount Higby “almost wholly consisting of steep rocky hills, and very stony land, we judge … to be very mean, and of little value.”2

The Eli Whitney Museum, Whitneyville, Connecticut. Taking advantage of the waterpower available at the traprock ledges between East Rock and Mill Rock north of New Haven in 1798, Eli Whitney, inventor of the cotton gin, revolutionized American manufacturing by using interchangeable parts to produce firearms and other metal goods. Local traprock was used to build many structures, including the coal shed seen here, through Ithiel Town’s innovative lattice-truss bridge. An icon of the New England landscape, Town’s modular design was an efficient and cost-saving solution for crossing the numerous streams and rivers in the region.

View of Hartford from Talcott Mountain near Farmington, Connecticut. An economic powerhouse founded on finance, precision manufacturing, and tobacco, Hartford long boasted the highest per capita income in the United States. Referring to its opulent homes, magnificent civic architecture, and shady, elm tree–lined streets, Hartford resident Samuel Clemens, better known as Mark Twain, stated, “Of all the beautiful towns it has been my fortune to see, this is the chief…. You do not know what beauty is if you have not been here.”

Lyman Orchards, which has been providing high-quality fruit and produce since 1741, is a major tourist attraction featuring a farm market, pick-your-own fruits and pumpkins, seasonal activities, and three golf courses.

Established on the northern flank of Sleeping Giant ridge in 1904, Blue Hills Orchard overlooks Meriden’s Hanging Hills—from left (west) to right (east), West Peak, East Peak, Merimere Notch, and South Mountain. The prominent “step” beneath West Peak (left) is the Talcott Basalt, the oldest (lowest) lava flow in the Connecticut Valley.

Taking advantage of the long steady slopes and snowy New England winters, Mount Tom Ski Area in Holyoke, Massachusetts, and Powder Hill Ski Area (now Powder Ridge) at Beseck Mountain in Middlefield, Connecticut, were developed during the alpine-skiing boom of the mid-twentieth century.

Postcards from 1960s: Mount Tom Ski Area; the “Big Tom” trail; NASTAR race day at Mount Tom; Powder Hill Ski Area. Images: author’s collection.

By the late 1800s, however, the growth of the major cities and towns brought a newfound appreciation of the traprock hills as valuable watersheds, and numerous water-supply reservoirs were constructed along the length of the Connecticut Valley. Even in the modern era, the formidable slopes, shallow depth to bedrock, and the difficulties of providing water and on-site sewage treatment precluded most residential and commercial developments on the traprock hills. As a result, the volcanic ridges remained largely undeveloped, becoming the most important natural corridor in southern New England, a vital green belt called “Connecticut’s Central Park” by Wesleyan professor Jelle de Boer.

Meteorologists associate the Connecticut Valley with a distinct climate corridor in southern New England typified by warm humid summers and mild winters in comparison to the cooler surrounding hills. The floor of the Connecticut Valley rises from sea level at New Haven to an average of about 150 feet above sea level near Northampton; many glacial hills and terraces form elevations over 250 feet throughout the valley. As a result of its generally moderate elevations the Connecticut Valley enjoys a long growing season, averaging about 165 days in Hartford, but ranging from a high of 207 days in New Haven to a low of 125 days in Amherst. Precipitation is evenly distributed throughout the year, but occasional droughty periods typically occur in late summer. The central and northern Connecticut Valley average about 45 inches of precipitation annually; the southern coastal region near New Haven is slightly wetter with about 47 inches of precipitation. Summers in the Connecticut Valley are warm and humid, with an average high temperature in July of about 82°F. The generally mild winters have average high temperatures ranging between 30°F and 40°F, characterized by rain and freezing rain near New Haven, and snow north of Hartford.

The cold average winter temperatures and the long steady slopes of the traprock ridges fostered the development of two major ski areas in the Connecticut Valley. Powder Ridge Ski Area on Beseck Mountain in Middlefield, Connecticut, has been in operation nearly continuously since the 1950s. Mount Tom Ski Area operated on the traprock ridge of the same name near Holyoke from 1962 to 1998. Both Powder Ridge and Mount Tom ski areas were pioneers in the technology of snowmaking, necessary to supplement the unreliable natural snow.

For physical geographers and artists the signature landscape elements of the Connecticut Valley are the “tilted” traprock ridges, or cuestas, with steep cliffs on their upturned edges and extensive upper surfaces sloping about 15 degrees. The ridges generally have west-facing cliffs and east-dipping slopes, but their particular configuration depends on the local trend of geologic structures. In the southern Connecticut Valley, the crescent-shaped trends of Totoket Mountain and Saltonstall Ridge result from regional-scale folds in the rock layers. A broad fold also creates the unusual east-west orientation of the Holyoke Range in the northern Connecticut Valley. Numerous faults that offset the traprock layers in the central Connecticut Valley created the spectacular “crag and notch” topography in the picturesque region from Mount Higby to Ragged Mountain.

Now part of the Meriden Land Trust, the green pastures of the former Bilger Dairy nestle beneath the cliffs of Chauncey Peak, Meriden, Connecticut. Dozens of family-owned dairy farms once flourished on the rolling glacial hills in the central Connecticut Valley. Today, only a few working dairy farms remain.

Snow softens the traprock landscapes at the former Bilger Dairy farm in Meriden. The early twentieth-century farm buildings seen here were built on ledges and outcrops of lava.

Hayfields in the central Connecticut Valley. With warm, moist summers and mild but often snowy winters, the Connecticut Valley enjoys the longest frost-free growing period in southern New England, exclusive of the coastal zone. Owing to the favorable climate, the Connecticut Valley produced some of the highest and most profitable yields of hay and corn in the nation in the early to mid-nineteenth century. Westfield Road, Meriden.

The Hanging Hills, including, from right rear to middle foreground, East Peak, Merimere Notch, South Mountain, Cathole Notch, and Cathole Peak, are the most rugged and picturesque traprock landforms in the Connecticut Valley. Termed cuestas by physical geographers, the characteristic “tilted” landforms were created by eons of earth movement and erosion. View from Chaucey Peak.

Rising abruptly in amphitheater-like ranks of rugged talus slopes and sheer cliffs, the traprock hills of the Connecticut Valley have a greater topographic prominence than many of the taller but more rounded mountains in New England. Thus, these “mountainous hills” project a more dramatic alpine aspect than anticipated from their relatively moderate elevations. For example, the southern cliffs of East Rock and West Rock near New Haven reach elevations of only about 350 feet and 400 feet, respectively, but because they rise in sheer cliffs from the tidal creeks at their base, they tower over the city, and once served as important landmarks for ships navigating Long Island Sound. A great east-west-oriented inlier of the Western Range, the Sleeping Giant massif (el. 708 ft.) in Hamden commands the Quinnipiac River lowlands as the largest isolated traprock landform in the Connecticut Valley. Noteworthy as the highest summits near the Atlantic coast south of Maine, West Peak (el. 1,024 ft.) and East Peak (el. 978 ft.) of Meriden’s Hanging Hills similarly dominate the topography of the central Connecticut Valley. Mount Tom (el. 1,202 ft.), the tallest traprock summit in the Connecticut Valley, towers more than 1,000 feet above the Manhan River valley near Easthampton, Massachusetts. Nearby, the western cliffs and ledges of Mount Holyoke drop more than 800 feet to the extensive agricultural fields on the Connecticut River floodplain.

Because of the sheer number of traprock peaks, crags, cliffs, and ridges making up the volcanic landforms of the Connecticut Valley, and a long history of human occupation, a large number of formal and informal names have been attached to the hills. Many of the designations have changed since colonial times, and the geographic names also vary with the local frame of reference; thus, East Mountain may well be West Mountain, depending on one’s point of view. The nomenclature of the traprock hills is based on the following: geography (East Rock, West Rock, West Peak, East Mountain, South Mountain); topography and appearance (Ragged Mountain, Peak Mountain, Pinnacle Rock, Short Mountain, High Rock, Tri-Mountain, Bluff Head, Sugarloaf, the Hedgehog); nearby towns (Farmington Mountain, Meriden Mountain, Avon Mountain, West Suffield Mountain); wildlife (Rattlesnake Mountain, Rabbit Rock, Cathole Peak, Goat Peak); historic associations (Mount Tom, Mount Holyoke, Chauncey Peak, Mount Higby, Peter’s Rock, Hachett’s Hill); the first inhabitants (Totoket, Pistapaug, Manitook, Nonotuck, Norwottock); colors (Black Rock, Red Rock, Blue Hills); and tales and legends (Mount Lamentation, King Philip Mountain).

Rising to an impressive elevation of 1,024 feet, West Peak (background) is the highest traprock summit in the Connecticut Valley south of Mount Tom in Massachusetts, and the tallest peak located within twenty-five miles of the Atlantic coast south of Maine. View from Ragged Mountain.

Illuminated by evening alpenglow, Ragged Mountain’s sheer cliffs project an alpine majesty lacking in many of the taller, but more rounded, mountains of New England.

In the legends of the Quinnipiac River tribes, Sleeping Giant (Mount Carmel) ridge was the reclining form of the giant, Hobbomock, put to sleep for all time for his mischievous deeds. Today, the diabase ridge is part of popular Sleeping Giant State Park, where dozens of hiking trails, a stone lookout tower, and picnic facilities await outdoor enthusiasts.

The “blue hills” of the Western Range stand high above the misty Quinnipiac River lowland. From north to south along the horizon (right to left), Peck Mountain, Mount Sanford, High Rock, and the north end of West Rock Ridge form a line of lesser-known traprock peaks on the southwestern edge of the Connecticut Valley.

The two main trends of traprock hills in the Connecticut Valley result from slight differences in their geology. The Metacomet Mountains, from Saltonstall Ridge to Mount Holyoke, are made up of basalt, which is finegrained lava that cooled quickly at or near the surface. The Western Range, from East Rock to Manitook Mountain, formed from basaltic magma that cooled slowly beneath the surface in dikes and sills, creating a coarse-grained igneous rock called diabase.

The traprock hills follow two major trends through the Connecticut Valley. The main range forms a great “wall” of crags from Mount Holyoke in the north to Saltonstall Ridge near Long Island Sound. Benjamin Silliman described the particular linear arrangement of this range in 1820: “In many parts of this district, the country seems divided by stupendous walls, and the eye ranges along, league after league, without perceiving an avenue, or a place of egress.” This main range of lava flows are herein designated the Metacomet Mountains, to distinguish their particular topographic aspect, and to streamline the cumbersome geographic nomenclature of the Connecticut Valley (please refer to Note on Terminology and Usage).

The volcanic veins and dikes that follow the western side of the valley as a series of discontinuous ridges and hills were named the Western Range by the noted geographer William Morris Davis in 1898. The Western Range runs from West Rock near New Haven to Manitook Mountain in Suffield, Connecticut, near the Massachusetts border. The specific rock type (diabase, see below) and characteristic “massif” landforms distinguish the Western Range from the typical cuesta ridges of the Metacomet Mountains. Known mainly to local hikers, the remote summits of the Western Range are among the least disturbed areas in the Connecticut Valley. The hills of the Western Range also have the most colorful names of any of the Connecticut Valley traprock crags, including Sleeping Giant, Onion Mountain, the Hedgehog, and the Barndoor Hills. Among the most scenic landforms in the region, East Barndoor Hill (el. 580 ft.) and West Barndoor Hill (el. 640 ft.) in West Granby, Connecticut, form a particularly interesting pair of steep traprock promontories separated by an unusually deep and shady notch.