Читать книгу The Traprock Landscapes of New England - Peter M. LeTourneau - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеNOTE ON TERMINOLOGY AND USAGE

Nearly all the geographic locations and topographic features discussed in this work are found in Connecticut and Massachusetts. Therefore, to spare the reader the tedious repetition of the state names, the author assumes that the reader will refer to the included maps, and has, or will gain, a passing knowledge of the major towns and cities in the Connecticut Valley. Thus, it is obvious within the geographic context that Springfield refers to the city in Massachusetts, and New Haven to the coastal city in Connecticut.

The early Connecticut Valley settlers referred to the alluvial terraces bordering the major rivers as “intervales.” With easily worked, fertile, and well-watered soils, the intervales were important to the agricultural success of both the Native Americans and the Euro-Americans in the Connecticut Valley. The Connecticut Valley intervales rose to prominence as the most productive soils in the nation, a reputation based on high yields of grass and grains, and, beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, shade-grown and broadleaf tobacco. The term prospect was used in the nineteenth century to indicate a scenic view, hence, Prospect House on Mount Holyoke, Prospect Mountain, and so on.

Colloquial terms for basalt lava include trap, trap rock, trap-rock, greenstone, bluestone—to name a few; following modern usage, we will use traprock for any igneous rock of volcanic origin in the Connecticut Valley. The word trap derives from the Swedish trappa meaning “stairs” or “steps,” and refers to the blocky appearance of the lava formations. We also use diabase rather than the European term dolerite for the coarse-grained rocks of basaltic composition found as dikes and sills intruded into the sedimentary layers.

The geographic term Connecticut Valley, or, as designated by William Morris Davis in the late 1800s, the Connecticut Valley Lowland, specifically refers to the elongate lowland underlain by sedimentary and volcanic rocks of Late Triassic and Early Jurassic age, extending from Greenfield, Massachusetts, to New Haven, Connecticut. Geologists refer to the main part of the Connecticut Valley as the Hartford basin and call the smaller northern extension the Deerfield basin, terms based on their particular rock types and geologic structures. The Connecticut River flows only through the northern and east-central part of the Connecticut Valley Lowland, from Gill, Massachusetts, to Middletown, Connecticut, where the river then cuts southeast through older Paleozoic-age crystalline rocks on its way to Long Island Sound.

Thus, the Connecticut River Valley and the Connecticut Valley, or Connecticut Valley Lowland, refer to separate but partly overlapping geographic features (see page 21). The northern part of the Connecticut Valley from Greenfield to Hatfield is known as the Deerfield Valley, a historic region of ancient towns and particularly fertile soils that support crops of high-quality tobacco. Although the Deerfield Valley shares a similar geologic origin, has a small area of traprock ridges, and is similarly rich in natural and cultural history, this work focuses on the main part of the Connecticut Valley, from Mount Holyoke in Amherst, Massachusetts, to East Rock in New Haven.

Although other traprock hills of similar geologic age and origin are found in eastern Pennsylvania, northern New Jersey and adjacent New York, the Southbury-Woodbury region of western Connecticut, and around the Bay of Fundy, none of those areas compare with the size, variety, visual interest, and cultural history of the volcanic landforms of the Connecticut Valley. Only the Palisades cliffs along the Hudson River are comparable in size and scenic qualities, but they lack the topographic complexity—the crags, promontories, notches, and mountain lakes—that make the Connecticut Valley so appealing.

Unlike the Berkshire, Green, and White Mountains, no common term was historically assigned to the chain of traprock ridges in the Connecticut Valley. Early writers including Silliman, Dana, and others, simply referred to the main series of lava ridges as the Greenstone Range, Main Trap Range, Mount Tom Range, Blue Mountains, and other indefinite geographic terms.

The name Metacomet Ridge has been used to refer to the major chain of lava hills since it was first popularized in Bell’s 1985 The Face of Connecticut; in 2008, the term was entered into the U.S. Board on Geographic Names database (GNIS—see http://geonames.usgs.gov). It remains a useful reference for the main trend of lava ridges, but the Metacomet Ridge does not encompass the series of diabase hills along the western side of the Connecticut Valley. In addition, the use of ridge causes confusion in the hierarchy of geographic names, since there are many local or subregional “ridges” in the Connecticut Valley, and the geographic term ridge refers to a local elevated feature of linear form. Raising its rank to “range” similarly causes problems, because there are a number of established “ranges” in the Connecticut Valley, including the Mount Tom Range and the Holyoke Range.

As the highest-rank geographic feature in the Connecticut Valley, the Metacomet Ridge, in this book is called the Metacomet Mountains, a term that respects the proper geographic hierarchy of the subordinate ranges, mountains, mounts, hills, and ridges, and more accurately reflects the rugged alpine aspect of the traprock crags. The name Western Range, first coined by William Morris Davis in 1898, is used for the chain of discontinuous diabase hills located along the western margin of the Connecticut Valley from West Rock to Manitook Mountain in Granby on the Massachusetts border.

The very definition of a mountain is also a matter of geographical debate, particularly where moderate elevations are characterized by extremely rugged terrain and sheer cliffs, as is the case with the traprock hills of the Connecticut Valley. Thus, the lava landforms have long been referred to as “mounts” and “mountains,” even though they fall short of the classic geographic definition of that term—“more than 2,000 feet of complex elevated terrain.”

Modern usage of the geographic term mountain varies widely, and, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, there are no standardized criteria for its definition, although abrupt topographic relief above the surrounding landscapes, and rugged terrain characterized by cliffs, promontories, and peaks, is implied. In the 1970s, the U.S. Board on Geographic Names abandoned its formal definition of a mountain as “1,000 feet of local relief,” instead deferring to local, historical, and anecdotal usage.

Until the 1920s, the British Ordinance Survey defined a mountain as any topographic feature with an elevation of 1,000 feet or more. A 1995 movie The Englishman Who Went up a Hill but Came down a Mountain, humorously recounted the true story of a “hill” in Wales that was redefined as a mountain in 1917 after the locals constructed a rock cairn reaching the desired elevation. A 13-foot-high stone cairn was likewise built by hikers on Mount Katahdin in Maine, to bring its official height of 5,267 feet up to 5,280 feet, or one mile above sea level. Modern usage in Great Britain informally defines landforms with elevations of 2,000 feet or more as mountains, although there is no formal agreement or recognized standard for a minimum elevation.

That redoubtable arbiter of all things linguistic, the Oxford English Dictionary (1989), offers perhaps the most practical definition of the geographic term: “A natural elevation of the earth’s surface rising more or less abruptly from the surrounding level, and attaining an altitude which, relatively to adjacent elevations, is impressive or notable.” Further, the OED states that the difference between hill and mountain “is largely a matter of local usage, and of the more or less mountainous character of the district; heights, which in one locality are called mountains being in another reckoned merely as hills. A more rounded and less rugged outline is also usually connoted by the name [hill].”

The mountain geographer John Gerard states that “altitude alone is not sufficient to define mountains”; relative relief compared to the surrounding terrain, slope angles, and rugged or scenic aspect, are all taken into account when defining mountains and hills. A notable recent trend in Great Britain, the land of great crag walkers and peak baggers, uses “relative relief” or “topographic prominence,” not only to distinguish between mountains and hills, but also to capture the effect of rugged terrain and steep slopes and cliffs in the hiking experience. Therefore, a very tall rounded landform may be less of a “mountain” than smaller but more rugged crags.

A rugged notch invites hikers and rock climbers into the traprock highlands at Ragged Mountain, Southington, Connecticut.

Given their extreme topographic relief, nearly all the traprock ridges in the Connecticut Valley more than qualify as mountains. Robert Louis Stevenson tackled this same geographic dilemma when attempting to capture the alpine qualities of the legendary Salisbury Crags near Edinburgh. He artfully concluded that the rugged but relatively modest landform, strikingly similar to East Rock in New Haven, was “a hill for magnitude, a mountain in virtue of its bold design” (Stevenson 1879, 21).

Inasmuch as a single ridge may be referred to as Mount Higby or Higby Mountain, for example, the designations mount, mountain, ridge, and hill are used interchangeably in this book for the sake of readability, the flow of ideas, and the reader’s patience.

The term traprock highlands (or traprock ridgelands, sensu LeTourneau, 2008) refers to the distinctive series of volcanic landforms in the Connecticut Valley, whether the rocks are of intrusive or extrusive origin. The traprock highlands are distinguished by their prominent elevations rising hundreds of feet above the valley floor, and by their characteristic tilted profile. According to geographic terminology, most of the Connecticut Valley traprock ridges may be classified as landforms called cuestas: hills formed from planiform or gently folded layers of rock that tilt, or dip, up to thirty degrees from horizontal (a hogback tilts more than thirty degrees). Cuestas are characterized by steep cliffs on their uphill, or upturned, edges, and may feature vast piles of broken rock, or talus, lying beneath the cliffs.

This book also designates the region from Ragged Mountain in Southington to Beseck Mountain in Middlefield as the High Peaks District because it displays the most dramatic “ridge and notch” topography in the Connecticut Valley, includes several of the highest summits, and has a striking similarity to the renowned Peak District in Derbyshire, England. In 1889, the leading American geographer of his time, William Morris Davis of Harvard, declared: “The district of the Hanging Hills, between Meriden and Farmington, is among the most picturesque in southern New England” (Davis 1889, 78).

It is interesting to note that for centuries writers and artists have celebrated the similar rocky crags, or “fells,” and sheer cliffs, or “edges,” of northern England, including those in the Pennine Hills, the Yorkshire Dales, and the Peak District. Alfred Wainwright, the inveterate British fell walker, published an enormously popular series of illustrated hiking guides, still used today, featuring the crags of northern England. Wainwright Walks, a popular BBC television series, traced Wainwright’s footsteps along landscapes remarkably similar to those of the Connecticut Valley. Had Wainwright ever traveled to Mount Holyoke, the Hanging Hills, or other traprock crags, he would have immediately felt at home.

Elevations cited in this book are measured in feet above mean sea level and were obtained mainly from the topographic maps and online databases of the U.S. Geological Survey, supplemented by trail maps from parks and preserves, and other resources. Accurate determination of the altitude of the most significant topographic elevations on the traprock summits proved to be one of the most challenging, and ultimately unsatisfying, tasks of this study. One expects that the spot elevations could easily, and consistently, be obtained from U.S. Geological Survey topographic maps, but that is not the case. In many instances, named prominences do not have accompanying spot elevations. To further compound the difficulties, the highest elevations are often not consistent with the elevations of named ledges or summits or surveying benchmarks, although they may be located nearby. For example, the highest point on West Rock Ridge is well north of the southern promontory called West Rock. In addition, many spot elevations are posted on “false summits” owing to the necessities of surveying, access, and land cover.

Comparing the USGS topographic map spot elevations with the GNIS creates additional difficulties. For example, the USGS topographic map gives a spot elevation of 1,024 feet for West Peak in the Hanging Hills; GNIS lists the elevation as 1,007. The “spot elevation” tool on the U.S. National Map Viewer was also used to query elevations at specific locations on topographic maps or aerial photographs based on the 2010 LIDAR (laser interferometry distance and ranging), a state-of-the-art satellite-based system of determining topographic elevations. Therefore, the elevations given in this book are based on the “best available” information and may differ from elevations cited in other works or GPS measurements.

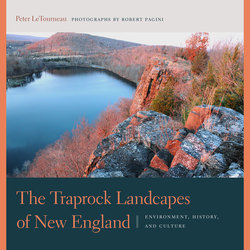

THE TRAPROCK LANDSCAPES OF NEW ENGLAND