Читать книгу The Traprock Landscapes of New England - Peter M. LeTourneau - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

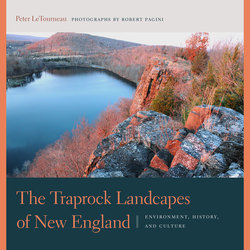

ОглавлениеMoonrise over the cliffs of South Mountain. Basalt is the most abundant crustal rock type on both the earth and the moon. The lunar “seas” were formed from enormous outpourings of basalt lava roughly 3 billion years ago. Radiometric ages determined from the samples of the CAMP basalts indicate that the lava flows of the Connecticut Valley are approximately 201 million years old.

3

Born of Fire

TRAPROCK GEOLOGY

Eruptions … took place from great fissures … of the earth’s crust. The lava which then came up and filled the fissures, and in many places outflowed, is the rock we now call trap.

James D. Dana, On the Four Rocks of the New Haven Region (1898)

The story of the Connecticut Valley begins in the early Mesozoic era (the age of dinosaurs), a time when the continents were joined in a single large landmass, or supercontinent, called Pangaea (“all land”). During the Late Triassic period, beginning about 220 million years ago, global tectonic forces caused the crust of Pangaea to thin and separate, a precursor to the eventual formation of the early Atlantic Ocean in the Middle Jurassic, around 160 million years ago.

The thinning and fracturing, or “rifting,” of the continental crust was accompanied, and in part caused by, an enormous plume of basalt magma rising from the upper mantle and lower crust (melted rock beneath the surface is called magma; lava is magma that cooled at or near the earth’s surface).

Approximately 200 million years ago the magma plume reached the surface, and voluminous quantities of lava erupted through cracks and fissures, flooding huge areas of the proto–North Atlantic region with basalt. The low-viscosity (very fluid) lava produced by the fissure volcanoes formed great “lakes” of lava in the low-lying rift valleys. Most of the traprock ridges and hills that dominate the landscape of the Connecticut Valley are the tilted and eroded remnants of these enormous lava flows.

Some of the magma did not make it to the surface, but instead cooled in cracks and veins forming dikes (vertically oriented bodies) and sills (roughly flat-lying layers or lenses). The entire Western Range, from East Rock in New Haven to Manitook Mountain in Suffield, including Mount Carmel in Hamden, are intrusive dikes and sills that have been exposed by erosion of the less resistant surrounding sedimentary rocks. A large number of dikes and sills also occur in East Haven, North Haven, and North Branford in the southeastern part of the Connecticut Valley.

Other large-scale dikes, including feeders for the lava flows, cut through the older Paleozoic-age rocks outside the Connecticut Valley, and in some cases form linear features that can be traced for hundreds of miles across the landscapes of eastern North America, the Iberian Peninsula, northwest Africa, and northeastern South America. On large-scale maps, these dikes form a distinct radial pattern pointing toward the main magma plume, or “hot spot,” located near the southeastern U.S. Atlantic margin.

The volcanic rocks of the Connecticut Valley are part of one of the largest terrestrial eruptions of basalt in the geologic record—only the extensive lava flows of the Columbia River plateau in the northwestern United States, the Siberian Traps, or India’s Deccan Traps are comparable. Volcanic rocks correlating in age with the Connecticut Valley basalts are found in South America, North Africa, and western Europe; for convenience this entire suite of Triassic-Jurassic-age volcanic rocks is termed the central Atlantic magmatic province, or CAMP.

In eastern North America the CAMP basalts form picturesque landforms such as Mount Pony near Culpeper, Virginia; the Watchung Mountains in New Jersey; the Palisades cliffs along the Hudson River; the Orenaug Hills in the Southbury-Woodbury area of Connecticut; the Pocumtuck Hills of the Deerfield Valley; and North Mountain on the Bay of Fundy. The vast quantities of carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and volcanic ash that accompanied the CAMP eruptions are implicated in global climate change and disruptions of the biosphere at the Triassic-Jurassic boundary that, in part, led to the rise of the dinosaurs in the Early Jurassic period.

The supercontinent of Pangaea during the Early Jurassic, about 200 million years ago. The traprock hills of the Connecticut Valley belong to the central Atlantic magmatic province (CAMP), one of the largest outpourings of continental basalt lava in the earth’s history. Illustration adapted from Kious and Tilling 1999; Marzoli et al. 1999; Goldberg et al. 2010; and Whiteside et al. 2010.

THE GREAT RIFT VALLEYS OF PANGAEA

Along with the eruption of the CAMP basalts, the geologic forces that were splitting the crust of Pangaea along the future Atlantic margin also created a series of elongate troughs, or “rift” basins, very similar in shape and size to the present-day great rift valleys of East Africa. The East African valleys containing Lake Malawi, Lake Tanganyika, and Lake Rukwa, among others, are good modern analogues for the size, shape, and regional configuration of the Triassic- and Jurassic-age rift basins of eastern North America. The interesting rocks, useful minerals, valuable coal deposits, and unique fossils found in the North American rift valleys have attracted the attention of geologists from North America and Europe since the 1800s.

As the regional-scale blocks of continental crust subsided like trap doors along active faults, large quantities of sediment washed down from the surrounding igneous and metamorphic uplands and filled the rift valleys; in the Connecticut Valley, more than three miles of sediment and interlayered basalt accumulated while the rift was active during the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic. The sedimentary rocks in the Connecticut Valley consist mainly of red-brown sandstone, siltstone, and shale, deposited in rivers, floodplains, and shallow lakes. Layers of black shale, some containing well-preserved fossil fish, plants, and other remains of early Mesozoic aquatic life, reveal the presence of deep lakes that filled the valley during humid climatic intervals. During dry periods, ephemeral streams, sand dunes, saline lakes, and mud flats occupied the valley floor.

Distribution of exposed and subsurface Triassic-Jurassic–age continental rift basins in eastern North America.