Читать книгу What Happened to Mickey? - Peter McSherry - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER SIX

ОглавлениеJack Shea and the Port Credit Bank Robbery (December 9, 1938–January 21, 1939)

On Friday, December 9, 1938, a month before the Windsor Murder, Jack Shea, as he would later testify, was one of three gunmen who robbed the Canadian Bank of Commerce in the Village of Port Credit, 12 miles west of Toronto, of $2,732.48. This violent crime, which for nearly a year afterwards was routinely referred to in the Toronto-area press as “the Port Credit bank robbery,” was absolutely essential to the charge of murder in the death of James Albert Windsor being preferred against Mickey McDonald and his brother, Alex MacDonald, and, similarly, essential to the eventual disposition of that charge against Mickey. For nearly a year, the two prosecutions — the murder and the bank robbery — were anything but mutually exclusive in the eyes of the Attorney General of Ontario, the Crown Attorneys of York and Peel Counties, the Ontario Provincial Police, the Toronto Police, the Port Credit Police, the attorneys for all of the defendants in the two criminal cases, the defendants themselves, the Toronto and area press, and the interested public.

The son of a Montreal policeman and a well-spoken former student at McGill University, John Roderick Shea was a strange duck to be mixed up with the likes of Mickey McDonald and Leo Gauthier. At different times, Shea claimed to be a chartered accountant and a stock broker who had been worth $90,000 before the Crash of 1929 — and he was believed by some to be both. An OPP wanted circular, dated December 31, 1938, described John Roderick Shea, aged 36, as a man of slim build, about 6 feet tall, weighing 165 pounds, having a thin face, a dark complexion, blue eyes, and “a very pleasant and talkative manner.” He was also said to be a thief who “drinks, bets horses, and is a ladies man.”[1]

In 1930, Jack Shea was convicted of forgery, and uttering and false pretenses at Winnipeg, Manitoba, and sentenced to two years in Stony Mountain Penitentiary. Four years later, in February 1934, Shea was one of a gang of shopbreakers who made off with 160 parcels of silk, valued at $10,000, the property of the Canadian Celanese Company, at 106 Spadina Avenue, Toronto. The thieves broke through a brick wall at night and loaded the silk onto a rented livery truck. On his way to Montreal with the stolen goods, Shea skidded the truck into a ditch on an icy Highway 2, near Cardinal, Ontario, and was arrested later in Toronto. The others involved were not caught and were never certainly identified.[2] On September 29, 1934, a jury convicted Shea of shopbreaking and, three days later, he was sentenced by a County Court judge to five years in Kingston Penitentiary. While awaiting his day in court, Shea cunningly broke out of the Don Jail and was chased through the Don Flats, and along a residential street east of the Don Valley.[3] He was found hiding in the yard of Withrow Public School. His twenty minutes of freedom cost a year in the lockup, concurrent with the shopbreaking sentence.

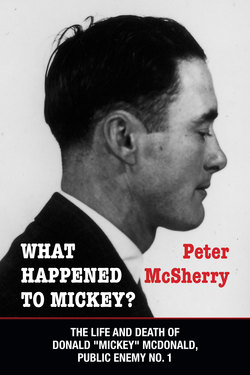

John R. “Jack” Shea, as he looked on October 13, 1934. One of the Port Credit bank robbers of December 9, 1938, Shea would testify against his partners in that crime as well as against Mickey and Alex MacDonald for the murder of Jimmy Windsor. (Library and Archives Canada)

Any competent bank robber knows that the robbery is the easy part and the getaway is the hard part. The Port Credit robbers botched the robbery, almost committing murder, and planned their getaway so poorly that, 90 minutes after the stickup, Shea was certain to be going back to prison as a consequence. Another of the three talked about the robbery — and to the wrong person. Inexperience, financial desperation, alcohol, and stupidity foiled them, though Jack Shea and Alex MacDonald were certainly bright men, and Shea and Gauthier were experienced criminals.

In the days before the robbery took place, Mickey and Leo Gauthier were both seen in and around Shea’s rooming house at 48 Twenty-Ninth Street in the Village of Long Branch, and in the beverage room of a nearby hotel, where the three were sufficiently apparent that a sharp-witted bookmaker, who operated from there, was later able to finger them as the bank robbers to the police. Shea, Mickey, and Gauthier were supposed to work “the score,” but Mickey went on a drinking spree instead. Teenaged Alex MacDonald, who barely knew the other ex-convicts, went to a beer parlour with them and asked in on “the job.” After four months of operating Pop’s Lunch, a Parkdale food counter and delivery service that his father had bought for him, Alex was tired of working for a living. He wanted to go out to British Columbia and figured “easy money” was the way to get there. Alex had already served a reformatory term for possession of burglary tools and another for riotous destruction of property while an inmate of the Guelph Reformatory.

About 11:40 a.m. that bleak Friday, the three robbers, all wearing coveralls, peaked caps, and cotton gloves, strutted into the Port Credit Bank of Commerce and pulled revolvers.

“All right, this is a holdup. Get down on the floor, all of you,” Gauthier barked.

Accountant Ray Bryant, furthest from the door, did not properly hear the instruction and made an unlucky move to fetch a book from his desk.

One of the robbers promptly shot him.

Hit in the right arm above the elbow, the accountant did not immediately fall, but blood was soon gushing through a quarter-sized hole in his arm, colouring his suit coat red.

“Stop shooting,” Jack Shea shouted, in fear of worse, his face visibly creased with anger and frustration.

After this, the gunmen — all unmasked — settled in to work and, using all manner of threats and foul language, forced four staff and one lady customer, who came in after the robbery was in progress, to lie face-down on the floor. Then Shea athletically jumped the bank’s counter and ransacked the teller’s cage, stuffing bills and change into the deep pockets of his coveralls.

One of the thieves spotted a man outside in a truck, who seemed too interested in what was going on inside, so after Gauthier refused to do it, Shea went out and brought the watcher into the bank at gunpoint. He was forced to lie face-down on the floor with the others by a gunman with “a snarly voice” — Gauthier — who threatened to kill him if he did not do as he was told.

Then the bandits turned their attention to the vault.

“Open that safe in a hurry or I’ll put a bullet through your head,” one of the robbers now menaced the wounded accountant.

Bryant, seeping blood, got up from the floor and did his best to meet the demand. He worked the half of the combination he knew with trembling fingers before managing to get it across to the robber who had a gun in his ribs — Shea — that the other half was known only by Norman Thacker, the bank’s teller. Thacker was brought to the vault in the same manner and made to open its door.

Meantime, in the customer area, Leo Gauthier — “the short man” — ushered two more patrons into the bank and, on pain of instant death, got them to lie down, faces to the floor. Alex watched the bank’s front entrance.

In a minute or two, Jack Shea had gathered up what money he found in the vault, not knowing there was $4,000 in a drawer he might have opened, but didn’t. The three thieves then left the bank in what seemed no particular hurry.

Outside, there were by then 30 or 40 people on the street, all or most of whom had already gathered that a robbery had taken place inside the Bank of Commerce.

The robbers briskly crossed the Lakeshore Road and went down a side street where, incredibly, they got into a pea-green light delivery truck with the words “Rogers-Deforest-Crosley-Majestic Radio” written on its side, and with two large loudspeakers on its top. A citizen took the license plate number of this preposterous getaway vehicle, which, it was shortly learned, was registered to Damon Stannah, the proprietor of Stannah’s Radio Store in Long Branch.

The police soon found out from Stannah that the usual driver of the truck was “J. Roddy Shea,” a salesman, radio repairman, and deliveryman, whom Stannah had hired earlier that year and whose pleasing manner and all-around ability he was quite impressed with. Stannah had considered making Shea the manager of the store but hesitated because three appliances Shea had sold had been paid for with worthless cheques totalling $450. He did not know that Shea had been released from Kingston Penitentiary on February 14, 1938, or that he was a convicted confidence man, cheque passer, shopbreaker, and jailbreaker. Nor did he know that Shea had been selling other radios and refrigerators for cash, then creating bogus paperwork that said the goods would be paid for “on time.” The truth was that Shea’s legitimate talents could not keep pace with his liking for fine whisky, fast women, and slow horses. The reason he had organized the bank robbery was that his scheme at the store was collapsing. It had reached the point where impending sales of electric goods for cash could not make all of the bogus time payments. He needed more money than he was earning and stealing at Stannah’s store — and he had to have it right away or he would be found out.

The green truck went west on the Lakeshore Highway, then north on Mississauga Road, where it was seen travelling at high speed. Somehow the robbers cut back east into the west end of Toronto, where most of the artifacts and clothing used in “the job” were dumped in an industrial lot in south Parkdale. After a fast split of the swag, Shea’s accomplices were dropped off not far from there and found their own ways home.

Shea, still driving Stannah’s truck, then went 4 or 5 miles west to 48 Twenty-Ninth Street, Long Branch, the rooming house where he lived. There he learned the police had already been looking for him. He knew then that the truck had been “made” — identified — and it would not be long before the police would be back knowing enough to suspect him of being much more than the victim of the theft of a vehicle. Shea quickly packed a bag and prevailed upon a casual friend to drive him into Toronto. Later that day he answered a classified ad for a rented room at 72 Gloucester Street, close by the city’s downtown. About 3 p.m., the police found Stannah’s truck on Twenty-Ninth Street. They had missed catching Jack Shea by an hour or more.

But far worse had already happened.

About 2:30 p.m., less than three hours after the robbery, a well-practised police informant had telephoned Constable Alex S. Wilson, at Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) headquarters at Queen’s Park, Toronto, claiming to know the identities of the three Port Credit bank robbers. Jack Shea and the MacDonalds perhaps never knew that the initial stool pigeon in the chain of events that would follow was Marjorie Constable, Leo Gauthier’s girlfriend of less than three weeks, whom OPP Inspector George MacKay years later would describe as “a good-looking woman from the Bruce Peninsula who slept with the crooks then gave information to the police about them.”[4] Gauthier, “the short man” at Port Credit, who, as Shea would later say, was quite drunk after the robbery, was untoward enough to have allowed his prostitute-girlfriend in on what ought to have been a professional secret. The eventual cost to Leo would be a 10-year sentence behind the grey limestone walls of Kingston Penitentiary. He was lucky that was all it was.

A half hour after the phone call, Wilson brought Miss Constable to Chief Inspector A.B. Boyd’s office, where she named Jack Shea, Leo Gauthier, and Alex MacDonald, as the three Port Credit robbers, and Alex as the quick-shooting gunman who wounded the accountant. Shea would later testify in a Brampton courtroom that Gauthier, not Alex, shot Bryant. The accountant did not know who shot him.

Notified by Shea that too much was already known at Long Branch, Gauthier vacated Marje Constable’s apartment in favour of an apartment on Lippincott Street. That meant the police, who obtained warrants for the arrest of the three perpetrators that same evening, could only immediately lay their hands on Alex, who resided at his parents’ home on Poplar Plains Road. They chose to wait on Alex’s arrest until Marje reconnected with Gauthier again.

A week later, Miss Constable — hungry for the Canadian Bankers’ Association’s long-standing reward of up to $5,000 for information leading to the arrest and conviction of any person or persons responsible for the robbery of any bank in Canada — again contacted P.C. Wilson, this time with information concerning Leo Gauthier’s whereabouts. At 7:20 that evening, by pre-arrangement with Marje, a combined squad of OPP and Toronto detectives arrested Gauthier at a table in May’s Restaurant at 404 College Street, where Leo had unsuspectingly kept a dinner date with his devious lady friend. At the same time, a similarly-constructed squad of police, including Port Credit Chief Telfer Wilson, arrested Alex MacDonald at his parents’ home.

Arrested for the Port Credit bank robbery on the information of his girlfriend, Marjorie Constable, Leo Gauthier would be convicted and sentenced to 10 years in Kingston. (Library and Archives Canada)

The two robbery suspects were taken to the detective offices at Toronto police headquarters, searched, separately interrogated, and placed in a line-up, where both were viewed by five eyewitnesses to the Port Credit bank robbery. The identification parade produced one positive identification of Alex MacDonald as having been seen walking outside the bank on December 9, and one tentative identification of Leo Gauthier as one of the men inside the bank. Peel County Crown Attorney A.G. Davis later characterized the identification evidence against the robbers as “weak.” Still, the two were charged with the crime. On December 22, a Brampton police magistrate remanded them and set bail at $7,500 for both. Alex made bail the next day. Gauthier got out on December 29.

Alex MacDonald, Mickey’s 19-year-old brother, took his older brother’s place in the Port Credit bank robbery. He would be charged with that crime and with the murder of Jimmy Windsor as well. (Library and Archives)

On the afternoon of December 30, 1938, at Gauthier’s request, Mickey McDonald met Jack Shea by appointment in a west end tavern. For three weeks, Shea had been laying low in the Gloucester Street room and, alternately, in a furnished apartment on Westmount Avenue, near Dufferin Street and St. Clair Avenue West. As a trusted ally, Mickey was asked to help Shea move to a more convenient location and, afterwards, to run errands for Shea, who, for obvious reasons, did not wish to walk the streets more than he had to. About 6:30 p.m., the pair answered a newspaper ad for a two-room furnished apartment over a grocery store at 209A Ossington Avenue. Shea introduced himself to Mrs. Caldare, the landlady, as “Dave Turner.” He said he was a railway inspector who was at times required to go out at night but rarely in the daytime. Mickey was introduced as “Clarke McCabe,” a friend. The rent was $6.25 a week.

Later, Mickey’s and Shea’s remembrances of what happened in the 12 days between Shea’s rental of the apartment and January 10, 1939, when Mickey was required to give himself up to face the charge of robbery with violence, would diverge sharply. There was agreement about the events of December 30, and agreement that, beginning late on the night of Tuesday, January 3, they both joined with Leo Gauthier on a train trip to Ottawa, where whatever they went there for turned into a drunken revel with two women who Mickey and Shea picked up in a Hull nightclub. Later, Jack Shea would testify that the real purpose of the Ottawa trip was to rob a bank and that Mickey badly needed $50 as an advance for his lawyer, Frank Regan, who had threatened not to be in court on January 10 unless the money was paid. Though they didn’t use the word, Mickey and Gauthier essentially told in court that the true purpose of the Ottawa misadventure was “tourism.” No bank was robbed, and Gauthier had to wire his father for enough money to get the entire group back to Toronto. They went and came back in less than three days, arriving home on the morning of Friday, January 6, poorer than before they went. Supposedly, Mickey still needed the all-important $50. The Windsor Murder happened 30 hours later.

Clearly, from what Shea and Mickey were afterwards able to agree on, Mickey was extraordinarily indiscreet with regard to Shea’s secret whereabouts. He brought several drinking friends to the apartment, none of whom, from a criminal perspective, ought to have been taken there. Gauthier was one thing, but, in the week between January 3 and January 10, Mickey also took to 209A Ossington Avenue Cecil “Doc” Clancy, a middle-aged bookmaker, who was a long-time boozing companion of his own; Teddy Wells, a twice-convicted safecracker who often tippled with Mickey and Clancy; and Joe Smith, an alcoholic gofer, who liked to hang around with criminals. To all of these, Mickey introduced Shea as “Dave Turner.” Clancy, for certain, knew better, as he had had prior contact with Jack Shea that Mickey did not know about, and he knew Shea was wanted for bank robbery. Mickey later testified that Shea took him into the apartment’s back room and asked, “Why did you bring that drunk here? He might talk.” Mickey said, though he couldn’t hear it, Clancy had Shea’s concern figured out, but, for obvious reasons, said nothing. According to Mickey, though both were by then badly befogged by drink, he and Clancy left shortly after for The Corner by taxi.[5]

On the morning of Friday, January 6, Mickey and Gauthier met Marjorie Constable not far from her stroll. All three went to 225 Sherbourne Street, near Dundas, where Leo and Marje rented another apartment. By the next evening, Marje had three broken ribs, such that Leo had to take her to the Toronto General Hospital, from where he managed to make three verifiable telephone calls roughly coincident with the time of the deadly incident at 247 Briar Hill Avenue. The telephone calls were Leo’s very-convenient alibi.

Whatever the story was at the time, it seems likely that Leo had Marje figured out and gave her a beating. Then, by design, he gave the appearance of forgiving her or of pretending to believe that he was wrong. The romance was on again. A criminal acquaintance of Mickey’s, interviewed years later, got it right when he said, “Leo would have suppressed her guilt for the sake of his own good health.”[6] The same, obviously, could be said for Marje. In their league, staying together, notwithstanding their mutual grievances, made sense. They both had to keep on breathing.

Yet Leo was the alcoholic flannel mouth that he was and, so, inevitably, Miss Constable made her third contact with P.C. Alex Wilson, by telephone, on the evening of Friday, January 20. By then Marje knew the address of Jack Shea’s hideout, that two revolvers were stashed in a buffet in the apartment and, supposedly, that Shea, Gauthier, and Alex MacDonald were planning to pull off another “score” over that weekend. P.C. Wilson immediately gave the information to the Toronto Police, who raided Shea’s apartment at 9 o’clock the following morning. A five-man squad of detectives, led by Detective-Sergeant John Hicks, managed to catch Shea sound asleep in bed and arrested him without incident. The early edition of that Saturday afternoon’s Evening Telegram flashed the banner: ARREST MAN FOR PORT CREDIT BANK HOLDUP. The officers had found two fully-loaded revolvers, a .32- and a .38-calibre, in the buffet. The police did not then, or ever, find the weapon that killed James Windsor — said by an expert witness at trial to have most likely been a Webley .455-calibre revolver.[7]

P.C. Wilson’s memorandum of these events, addressed to Chief Inspector Boyd and clock-dated Saturday, January 21, 10:30 a.m., ended with a pregnant sentence: “There is some suggestion that Shea may have been mixed up in the Windsor Murder of the 7th.”[8]

Now where might P.C. Wilson have got an idea like that? And who might have had her eyes on the $2,000 reward for the murderers of James Windsor?