Читать книгу What Happened to Mickey? - Peter McSherry - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER TWO

ОглавлениеToronto’s First Gangland Killing

(January 7–February 23, 1939)

Less than an hour after it happened, news of James Windsor’s death was on the radio. There was only minimal information. Prior to the mid-1930s, radio stations in Toronto did not have much news — and not until World War II did change really come. Thus, at the time of the Briar Hill Avenue shooting, real news was still thought to be in the newspapers and people looked for it there.

On Monday, January 9, the Windsor Murder, as the incident would soon be most often termed in the press, was the blackline of all three Toronto dailies, the Globe and Mail, the Toronto Daily Star, and the Evening Telegram. All represented the crime to their readers as “Toronto’s first Gangland killing,” and all linked the murder to previously-reported violence and “gang warfare” between cliques of criminals in the Jarvis and Dundas streets area, which had been a serious concern in the city for several months.[1] Another theory held that “Italian gangsters” — extortionists, perhaps local, perhaps from Hamilton, Detroit, or Buffalo — were the culprits behind the killing. The banner headline on the morning Globe, first paper on the street on Monday, January 9, blared: MURDER CLIMAXES GANG WAR; TWO HELD. Underneath, the lead story reflected the fear and the confused understanding that the killing engendered in the city. The main thread running through the lead stories of the Globe and The Star was that Windsor had been killed because he had refused to pay “protection money” to a gang that was intent on bleeding him. The Star’s account conjured up the worst of the horror in its first gripping sentence: “A gangland execution squad killed James Windsor in his Briar Hill Avenue home Saturday night before the eyes of his family.” The Star claimed that 32 Toronto bookmakers were known to have been victimized during the previous month. The Telegram, which did not specifically refer to the “protection racket,” told its readers that the murder was “obviously a case of gangland vengeance ... the first of its type that has ever occurred in Toronto ... the most cold-blooded in the history of Toronto ... the culmination of a long series of battles between Toronto gangs.” The papers printed pictures of Windsor, of his home, of the Windsor Bar-B-Q, of Lorraine Bromell, and of the eyewitnesses and others hiding their faces as they went in or out of police headquarters. There were diagrams of the inside of Windsor’s home — the murder scene. Photos of alleged suspects, Frank “Dago Kelly” Pallante and Albert “Patsy” Adams, both of whom the Toronto Police had seen fit to detain as vagrants, the catch-all holding charge of the day, were also published.

In 1939, Toronto was still “The Queen City,” “The City of Churches,” “Toronto the Good,” where, it was said, “On Sundays you could shoot a cannon ball down Yonge Street and not hit anybody, or anything, at all.”[2] The city was still then an unsophisticated, Wasp-ish Triple-A town, well-known for insular thinking and narrowness of outlook. A heavy-handed police force — backed by the city burghers, a conservative judiciary, most of the churches, a mostly conservative press, and such still-powerful national lobbies as the Lord’s Day Alliance and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union — enforced a plethora of civic by-laws that strictly monitored public morality and behaviour. In limited areas, though, the then so-called “consensual vices” — bookmaking, bootlegging, and prostitution — were usually allowed to exist, so long as they did not lead to bigger problems or there were no complaints that were persistent or could not otherwise be smoothed over. These so-called “victimless crimes” were thought by some to be more easily regulated that way and the police often got valuable information from those who were involved in them. Beyond that, the Toronto Police “gave all the trouble they could” to the city’s real criminal element, such as it was. The Vagrancy Act, patterned on an 1824 British statute in use against prostitutes and other “loose, idle or disorderly person(s) or vagrant(s) ... found wandering abroad and not giving a good account of themself...” was a usable tool readily employed against those suspected of serious crimes as well as those who did not show respect for the police.[3]

“With the Vag Act, you could keep them in jail for at least a week,” remembered Art Keay, a plainclothesman of that era in downtown No. 2 Division. In 1978, Mr. Keay spoke, too, of a police method that was then more often resorted to than in a later time: “Do you know what “tried summarily” meant? You gave them a good going over. The police were more physical in those days because there was never any such thing as a civil action against a policeman. You never heard of it. People had a lot more respect for the uniform in those days....”[4]

The upside of all of this was that, in a city of 650,000 — with several hundred thousand more in adjoining townships and villages — there was not a lot of crime.[5] In fact, there had been only one murder in the City of Toronto in each of the three previous lean years, 1936, 1937, and 1938.

In such a danger-free community, the fear engendered by “the Windsor Murder” was pervasive. The extraordinary brutality of the killing and the fact the perpetrators had boldly invaded a home in one of a safe city’s safest sections served to raise public anxiety and concern to a level rarely, if ever, known before. Initially, eyewitnesses to the murder had given investigating officers to understand that the perpetrators appeared to be Italians. Their descriptions in the press reflected this fact. In conservative, law-abiding Toronto, this conjured up a style of crime that the local citizenry was already quite fearful of: “American-style organized crime,” which was then largely a press euphemism for what was perceived to be Mafia-style organized crime. “Al Capone shooting people to death in front of the Rosedale United Church on Glen Road on every other weekday,” was how Maurice LaTour, an old safecracker, laughingly exaggerated this fear in an interview in 1979.[6] Since the early 1920s, in the days of the Ontario Temperance Act (OTA), this anxiety had grown into a not-so-far-off palpable reality. Rocco Perri of Hamilton, once self-styled as the “King of the Bootleggers,” was thought to hold sway by violence, and the threat of violence, only 40 miles distant via the Lakeshore Highway.

Within a few hours of the murder, Attorney General Gordon Conant, Toronto Mayor Ralph Day, Chief Constable D.C. Draper, and the Toronto Board of Police Commissioners, all issued statements designed to assure the worried public that organized crime would not be tolerated within any of their jurisdictions or areas of authority. On Monday, January 9, the Province of Ontario posted a $1,000 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the perpetrators. The City of Toronto and the Board of Police Commissioners both announced $500 rewards, bringing the total on offer to $2,000. This was money meant to get police informants talking. A police circular dated Tuesday, January 10, published descriptions of four perpetrators, two of whom, including the shooter’s description, carried the phrase “looked like an Italian.” The medium-sized killer, supposedly Italian-looking, was said to have “a dark, sallow complexion,” a regular nose that was “fairly wide at the nostrils,” and teeth that were “decayed and wide-apart.”[7]

The Windsor Murder had immediate effects on the street. Bookmakers, and to a lesser extent bootleggers, became more conservative in how, and with whom, they did business. Many suspended operations entirely. The Toronto Police, called on the carpet in an editorial in the Evening Telegram titled “Apparent Laxity of Police Must Be Explained,” were asked to give reasons why such social evils as bookmaking and bootlegging were permitted to exist in Toronto at all.[8] The public response of the police was to increase the frequency and the publicity surrounding the activities of the hard-hitting raiding squad that targeted such racketeers, which had been in place since May 1938 — this, now on the apparent reasoning that, if no one was making money by taking bets or selling illicit liquor, no one else would likely try to extort them or kill them. Reporters followed the Gang-Busting Squad as they beat down the doors of bookmakers and booze-can operators with axes and battering rams.

At 247 Briar Hill Avenue, James Windsor’s body lay in an open satin-lined casket in a flower-filled front room for two and a half days. Uniformed police stood guard at the front of the house, as detectives mingled with those inside. At 9 a.m., Wednesday, January 11, a requiem mass was sung for the bookmaker at St. Monica’s Roman Catholic Church on Broadway Avenue. The church was full with mourners, plainclothesmen, and those of the curious who could not be kept out. About 75 people followed a funeral car to the graveside interment in Mount Hope Cemetery, where women covered their faces with black veils and men turned up their collars, so as not to show up in any pictures in the daily press or in some scandal paper like The Tattler.[9] Speculation that the funeral might turn into a rowdy circus, as had that of Rocco Perri’s murdered wife, Bessie, in August 1930, when thousands of unruly “morbids” and gawkers pushed and shoved the mourners, even almost knocking the weeping husband into the grave, proved unfounded.[10] News accounts of the Windsor funeral concentrated on the quiet fear that hung over the event and the fact, considered mildly scandalous by some, that James Windsor was interred in a burial plot with a woman who was not his legally-married wife.

The Windsor news story was Page One in all three dailies for a week and appeared semi-regularly after that till February 23, 1939, when the Toronto Police arrested two brothers for the murder. After that the focus became the alleged murderers, not the murder or its solution. Windsor’s life was picked over thoroughly, beginning with his childhood in a hard-scrabble section of Parkdale. He had worked as a bartender in the Ocean House at Sunnyside before the Ontario Temperance Act came on in 1916, affording him the opportunity to make a lot more money selling liquor illegally than ever he had made doing so within the law.[11] By 1923, Windsor was worth enough to put a down payment on the Briar Hill Avenue house. He was by then long-since split from his wife and four children, and was living with Lavina “Violet” Frawley, the lady in the grave, who had predeceased him by a year and a week. When Ontario Temperance ended in 1927, Windsor adapted and set up his bookmaking business. A story that he was worth $100,000 before the Stock Market Crash of 1929 was likely a pressman’s exaggeration. It seems impossible to credit stories such as the one that named Windsor as an associate of William “The Butcher” Leuchter, a Rocco Perri acolyte who was blown up in a car full of alcohol near Ann Arbor, Michigan, on November 30, 1938. More likely Jimmy Windsor’s long-before OTA career was that of a “one bottle man” who had quietly delivered liquor throughout Parkdale in an old car — and merely made an independent, if mildly illegal, living.

In the first week’s news there were several alternate theories as to why the bookie died. To some, including two of the eyewitnesses to the killing, the killer’s level of anger seemed to suggest a personal hatred of Windsor himself — revenge for some previous wrong or slight. There was a pressman’s yarn that said Windsor died for switching allegiance from one American gang to another, that three killers from Buffalo, in company with a Toronto “fingerman,” had done the murder. Then there were “the bag” stories — that “the bag” the killer was after was a small cloth pouch in which Windsor carried diamonds and other jewels in a hidden pocket in his trousers, and also the more likely tale that “the bag” was merely a bag-like, box-shaped carrying device in which Bar-B-Q receipts were taken home, a practice Windsor had discontinued months before. Inevitably, there was the suggestion that the bookie had brought about his own death by welching on a bet. Which his friends and professional acquaintances said he would never do. The most obvious thought, that Windsor was merely the victim of a robbery, got little mention, as the murderers hadn’t bothered to snatch jewellery that was very apparently worn by the three women in the house.

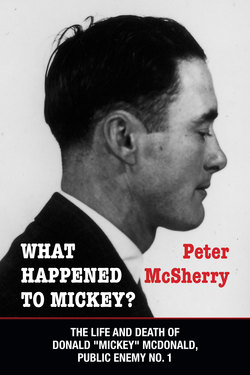

Eventually the public got tired of the murder story, as the public always does. There wasn’t much more to report or to invent. There were other stories that unsettled readers more, especially having to do with the impending war in Europe. Still, when 47 days after the event, the Toronto Police charged Donald “Mickey” MacDonald, a well-known local thief, and his teenaged brother, Alex, with the murder, Toronto breathed a small sigh of relief. Things would be that much safer on Glen Road, in Toronto the Good, for a little while longer.