Читать книгу What Happened to Mickey? - Peter McSherry - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER THREE

ОглавлениеMickey at the Corner

(1907–1938)

In May 1939, as part of the Windsor Murder investigation, Detective-Sergeant Alex McCathie summed up the man thought to be James Windsor’s actual killer in a report to Chief Inspector John Chisholm:

Donald (Mickey) McDonald has been known to me for a number of years, and during that time has always been engaged in criminal activities. On his own admission, these activities have covered the past fifteen years.... His known associates are practically all criminals and prostitutes, and to my knowledge he has never been engaged in any legitimate employment.[1]

Prior to the winter of 1938–1939, Mickey McDonald was seen by the Toronto Police as a small-time criminal of a type that was apt to become dangerous. As Toronto detectives knew him, Mickey was not a particularly clever thief. He drank too much, he talked too much, and, especially when drunk, was given to outbursts of erratic violence. By February 23, 1939, the day of his arrest for murder, Mickey had spent nearly seven of the preceding 15 years behind bars and he was then under sentence of another two years. Worse, from the police point of view, he had recently been arrested in possession of a revolver, with the apparent intention of using it to commit a crime.

In appearance, the adult Donald McDonald was medium-sized, fair-skinned, dark-haired, and clear of hazel eye. He dressed well and was almost always neat and trim. His left cheek wore a small, not unattractive mole. People noticed his normally pleasant demeanour, his usual politeness, and his outgoing manner. In the Toronto underworld of the day, such as it was, Mickey was thought to be both good-looking and dapper. Many women were charmed by him, to the extent that it was claimed he had numerous affairs and assignations. Detective-Sergeant John Nimmo, who became his eventual nemesis, at least twice testified to Mickey’s sense of humour when under the influence of alcohol. “He is very funny,” Nimmo observed in court. “In fact, better than going to a show.”[2]

He was born Donald John MacDonald on April 11, 1907, in Scotland, likely in the Highland city of Inverness, from where his parents, Alexander Robertson MacDonald and Margaret Renfrew MacDonald, originated. In March 1911, Donald’s father, looking for a better life for his family, came to Canada, alone, on board the 10,000-ton steamer Megantic, Liverpool to Halifax, as a “British Settler Third Class” — in ship’s steerage — with the equivalent of $88 Canadian on his person. MacDonald’s ticket into Canada was that he was prepared to work for a specified time as “a farm servant” in the Toronto area. By the summer of 1914, Alexander, his wife Margaret, known as “Maggie,” and their several youngsters, including “Donnie,” were settled together in a house at 7 Bird Avenue, near Dufferin Street and St. Clair Avenue, in Toronto’s west end.[3] The MacDonalds would eventually issue 10 children over a 24-year period, 9 of whom — 6 girls and 3 boys — lived to adulthood. Donald was the oldest boy.

After 1916, Alexander MacDonald laboured 25 years, shoeing delivery-wagon horses for the Canada Bread Company and, according to himself in May 1939, never missed a day’s work. Nor did he ever miss Sunday worship. He was a stern, square, God-fearing Scot and an active member of the Church of God, a conservative evangelical congregation then much given to tract distribution and street-corner preaching. According to a story, Mickey’s father, whose fixed sense of right and wrong was easily brought forth, was himself a street-corner preacher.

Donald attended Hughes and Earlscourt schools and got an elementary education in normal fashion. Even then, people noticed his politeness and outgoing personality. But by the time he reached the age of eleven, something had started to go wrong. The boy was stealing. His Juvenile Court record shows that he was convicted of six offences in the five years before he reached the age of sixteen. Theft, trespassing, shopbreaking and theft, disorderly conduct, and theft again were the charges. The worst happened in August 1919, when, aged 12, “Donnie” — his mother’s name for him — was put on probation and his father had to make restitution to a shopkeeper whose store was broken into. Otherwise, there were warnings, $2 fines, and another probation.

Age 14 and no longer in school, Donald reached a point in life where he was quite normally expected to work and bring home his wages. According to what he later told a counsellor in reformatory, he began work by labouring six months at the Dominion Shipbuilding Yards, where he was paid $14.40 a week. After that, he was a bellboy on a passenger ship that ran between Toronto and Prescott, Ontario, in the Thousand Islands. At other times, so he said, he was the driver of a Canada Bread Company truck and a chauffeur.

About this time, Donnie decided he would rather be “Donald McDonald” than “Donald MacDonald” and, later, he would consistently misrepresent that he was born in Canada, not Scotland. His religion, likely never practised, had become “Presbyterian,” his mother’s church, not the Church of God, to which he had been taken as a boy. His father’s thick Scottish brogue he probably did not like either. Years later, he said that he left home at sixteen.

In September 1925 came the first of Donald’s many appearances in Toronto Police Court. Aged 18, he had stolen the motorcar of a Lansdowne Avenue doctor, crashed it into another vehicle, then attacked the other driver. Magistrate J. Edmund Jones convicted him of auto theft and aggravated assault, and awarded a sentence of two years less a day, to be served on remand.[4] Donnie could not manage this leniency. A few days later, he and another troubled youth grabbed $15 from the cashbox of Josephine Columbo’s Davenport Road candy store and escaped in a waiting car. Detective Fred Skinner of the Ossington Avenue Station pulled the pair out of their beds in the early hours of the morning and charged them with robbery with violence. In court, however, likely after some parental begging, the two were allowed to plead guilty to simple theft. This time, though, when Magistrate Jones passed sentence of two years-less-a-day, Donald had to “do the time.” Many years later, Detective Skinner remembered Mickey as being both likeable and polite. “He often met me on the street. He would always stop to talk to me. He always called me ‘Mr. Skinner’,” recalled the detective.[5]

Donnie became Guelph Reformatory’s #37514 on October 6, 1925. He did not then, or later, serve time well. His Guelph medical sheet runs several pages and has to do with mostly trivial medical matters — colds, headaches, constipation. Likely the tensions of life “inside” caused him anxiety. He was a worrier who eventually developed a gastric ulcer, which had to be treated in Guelph and later in Kingston Penitentiary. He made a good impression where it mattered, though, and was released “on permit,” on September 27, 1926, to go to work. Six months later, on March 18, 1927, The Office of the Commissioner for the Extra Mural Employment of Sentenced Persons, at 40 Richmond Street West, Toronto, notified the Superintendent of Guelph Reformatory that Donald McDonald had “disappeared” and was therefore “unlawfully at large from your institution.”[6]

Why would such as Mickey want to work for wages when there was “easy money” — big money — to be made selling illicit liquor?

Mickey had escaped to Detroit, Michigan, where, according to the street story, he became for a time a distributor of good Canadian whisky on behalf of a Windsor racketeer named Raymond “Dolly” Quinton. This was the heyday of the Volstead Act — American Prohibition — when, even though the Province of Ontario was itself “dry” by reason of the Ontario Temperance Act, the federal government permitted the manufacture and sale of liquor “for export,” ostensibly only to countries where liquor consumption was legal. Along the Detroit River, on the Windsor side, every day congeries of rumrunners in boats both big and small, many of them rowboats, would pull up to any of a dozen or more government docks, sign a B-13 form — a declaration that they were buying liquor to take to “Cuba” or some other country where the consumption of alcohol was legal — then they would sell the liquor wherever they cared to. The usual destination from Windsor was, of course, Detroit, where good Canadian whisky was in high demand, but much whisky and other liquor was simply U-turned back into Ontario to be bootlegged throughout the province.

Mickey’s career in alcohol distribution could not have lasted long before he was pushed out of the game by the Detroit Police or, more likely, by competitors who were too tough to give an argument. But he adapted. In July 1930, at Detroit, as “Michael McDonald,” he was sentenced to from 9 months to 10 years for “indecent liberties,” a charge that he himself later variously described as having to do with his living with an underage girl, and as having to do with the making of pornographic pictures. He served the minimum 9 months in Michigan State Prison at Jackson, Michigan, then was released on April 10, 1931, the day before his twenty-fourth birthday.

Mickey learned much in the Michigan lockup, and, it seems, by the time of his release had chosen crime as his career. Now calling himself “Michael McDonald” — hence the nickname “Mickey” — he returned to Toronto and headed straight for Jarvis and Dundas streets, a location that, by this time, was becoming known as a gathering spot for bootleggers, prostitutes, drug dealers, assorted criminals, and all of their hangers-on and fellow travellers. “The Corner” was what those “in the know,” including the police, had begun calling the intersection. On the street, the term would hold up as such for the next 30 or 35 years.

Mickey was soon tied into a loosely-associated gang of shopbreakers who lived an expensive criminal lifestyle. They did “kickins” by night, spent their afternoons at racetracks, were often at bootlegging establishments, and often philandered among prostitutes. The gang’s usual target was women’s clothing stores, which yielded items that could be easily disposed of for cash.

On August 5, 1931, as “Michael McDonald,” Mickey appeared with two others before Magistrate Robert J. Browne charged with the theft of 130 ladies dresses from the store of L.A. Finch at 483 Bloor Street West. Associates Louis Gallow and Jimmy Douglas were convicted and sent “down East” for three years each, but the magistrate threw out the case against Mickey. Two nights later, Mickey celebrated by making a drunken show of refusing P.C. Fred Falconer’s suggestion that he “move along” from the corner of Church and Dundas streets. He was charged with “obstruct police.” That cost $50 and court costs on pain of 30 days in the Langstaff Jail Farm.

Then came the night in a Sherbourne Street booze can when Mickey McDonald, for no reason that made any sense, smashed a banjo over the head of a prostitute who was known on the streets as “The Old Gray Mare.” She was the wife of William “Big Bill” Cook, a pimp, drug dealer, and gunman, who was also the former doorman of the Chicory Inn, a roadhouse on the Lakeshore Highway in Clarkson. It was at the Chicory Inn that Bill Cook had famously shot Oscar Campbell, a thug at least as dangerous as himself who had previously bested Cook in a street fight by whacking him over the head with a hammer. A few months before the banjo incident, Cook was acquitted of shooting Campbell with intent to maim.

Big Bill caught up with Mickey inside Trotter’s Lunch, a Dundas Street East restaurant-cum-dive, at 4 a.m., Sunday, October 13. There followed a comic-opera attempt at murder, in which Mickey found the courage to physically attack Cook, who was 30 or more pounds heavier than he was, while Bill fired a gun at Mickey before he got the gun out of his own pocket and, so, shot himself in the leg. Cook was then beaten and kicked by Mickey and others among Trotter’s swanky clientele, one of whom grabbed Cook’s gun and left with it. In a state of high excitement, Mickey then clobbered the restaurant manager over the head with the receiver of his kitchen phone, when the man, somewhat ridiculously, tried to establish order in his place of business.

The next afternoon, at the Lakeshore Racetrack, Mickey met Detective Frank Crowe and, in a jocular conversation between “friendly enemies,” made the mistake of having too much to say about what had happened at Trotter’s. He would not afterward sign a statement naming Cook and wound up being charged with assault occasioning actual bodily harm on the restauranteur. Worse, he was bound over as a material witness against Big Bill, who was claiming to the police that he had been mysteriously shot on Sherbourne Street by a stranger. Cook’s coat, which had a bullet hole through the pocket, told the true story, while Mickey — who chose to maintain his reputation as “good people” — perjured himself, very obviously, in the interest of Bill Cook, a man he hated and who hated him. On December 17, 1931, again as “Michael McDonald,” Mickey pleaded guilty to aggravated assault before a County Court judge and was meted out a sentence of two years in prison. Twenty-nine days later, before Justice Hugh Edward Rose in the Supreme Court of Ontario, he pleaded guilty to perjury and was handed three years concurrent with the first sentence. Mickey smiled and wore an air of nonchalance at both proceedings.

As inmate #2479, McDonald spent his first 10 months in Kingston Penitentiary working in the canvas shop (“the mailbags”) where he toiled at the manufacture and repair of Canadian Postal Department mailbags. These were the last days of the Silent System and of a rigid set of prison rules and regulations put in place decades before. The Kingston riot of October 17, 1932, was the convicts’ idea of their first move in a process of change. At 3 p.m., about 450 of the institution’s 700 inmates walked away from their work and barricaded themselves in the Shop Dome before being overcome by guards with guns and herded back to their cells. Mickey McDonald was one of 32 later charged and tried before a County Court judge. Two guards and a shop instructor testified to having observed Mickey taking an active role in the riot, one saying that Mickey appeared to be giving orders in the Dome. Thus, on August 5, 1933, after a lengthy trial, again as “Michael McDonald,” Mickey was convicted of riotous destruction of property and sentenced to 6 months in reformatory, to be served after the completion of his Kingston sentence.

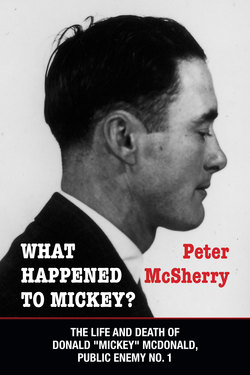

“Mickey” McDonald as photographed upon his first admission to Kingston Penitentiary on January 16, 1932. (Library and Archives Canada)

During the 33 months he was in “the Big House,” Mickey’s weight dropped from 161 to 138 pounds. A medical examination in September 1934 concluded, “This man is principally run down from a lack of exercise in the open air.”[7] A psychologist’s assessment stated, “At the present time he is quite embittered towards the penal system and feels that he was harshly treated. His father is regularly employed and has promised to obtain steady work for Michael when he is discharged from custody.”[8] As always, Mickey’s parents were worried and trying to help. Their letters to the right authorities got the result that Mickey was allowed to serve his six-month sentence in the Mimico Reformatory rather than in Guelph. But 13 days after Mickey entered Mimico, a jailhouse “rat” named him as being involved in sending out letters by the “underground method.” Superintendent J.R. Elliott interviewed Mickey and, the same day, reported to Deputy Provincial Secretary C.F. Neelands:

William “Big Bill” Cook, pimp, drug dealer, gunman, and the man who tried to shoot “Mickey” McDonald in Trotter’s Lunch in the early morning of October 13, 1931. (Library and Archives Canada)

I had hardly spoke to him when he flew into a rage in a threatening manner, calling me a Son-of-a B, Bastard etc., completely losing his head. He is a bad character….

He is now in the cells.

I will see him again in the morning, and if his attitude is not changed I will recommend the strap and possible removal to another institution.[9]

Given time to think, Mickey became cutely submissive. The cost of his tantrum was a charge of “Insolence to the Superintendent,” which lengthened his stay in Mimico by 26 days. He was released February 1, 1935.

He was soon back at The Corner, again mixing with others like himself who imagined the “easy money” of a life of crime, and the uncertain existence that came with it, were to be preferred to a life of honest labour. Twice in 1935 he was before the courts charged with offences related to shopbreaking. In May 1935, together with Jack Cosgrave and another man, Mickey was stopped in a rented truck in possession of a jimmy and several types of keys. The three were charged with “possession of housebreaking instruments.” The case got to court but all were acquitted. In September, Mickey and Leo Gauthier, a long-time associate, were arrested after a pursuit by car from the scene of a break-in at Hooper’s Drug Store at 391 Jarvis Street. They got off, perhaps because the taxi driver who fingered them to the police found reason to water down his story in court.

These days Mickey at times went about with a fat roll of bills in his pocket, which he soon frittered away on gambling and alcohol. He was often broke and asking for a loan. Then he was apt to turn into a mere street-corner clip-artist, rolling drunks or steering marks to rigged card games — any mean little “score” for a desperate buck.[10] The Toronto Police saw him as one of their “usual suspects” and would routinely pick him up and question him in connection with shop break-ins, house burglaries, and at least one armed robbery. In normal circumstances, Mickey’s disposition was sunny and pleasing, but, when down-on-his-luck and drunk, which he now often was, he was known to get nasty, to pick fights, to take his inner anger out on almost anyone who was handy at the moment. Years later, Jenny Law, a prostitute of the 1930s, remembered Mickey as good-looking, well-dressed, well-groomed “trouble.” He was, she said, barred from a lot of the tap rooms and bootlegging “joints” in the vicinity of The Corner. “He would go to a bootlegger’s, get drunk, and start a fight, so he wouldn’t have to pay,” Jenny remembered in a tone of wonderment.[11]

The MacDonald family, now renting a house at 3 Poplar Plains Road in central Toronto, saw Mickey as it suited him, although, as his mother later said, he made a practice of calling her on the phone every day.[12] When he did come home, he often brought one or more of his risky “friends.” His parents’ need to continue loving their wayward son allowed people with corrosive ideas, Mickey especially, to have exposure to their younger boys, Alex and Edwin. It was a mistake that would have serious consequences. Maggie MacDonald would live to see the day when all three of her sons were in federal prisons at the same time. Detective-Sergeant Alex McCathie, at least twice a visitor to the MacDonald home in 1935, went there on October 26 and, afterwards, reported:

.... armed with a search warrant and in company with other officers, I had occasion to search the home of the McDonald (sic) family. Upon entering the premises I was assured by Mrs. McDonald that none of the goods outlined in the search warrant were concealed in the premises, but on executing the warrant articles stolen from two shops which had been broken and entered in Toronto, and a store which had been broken and entered in Preston, Ontario, were found in practically every room in the house. Members of the family were found to be wearing stolen clothing, which they admitted had been brought to their home by John Cosgrave, a dangerous shopbreaker, an associate of Donald (Mickey) McDonald....

A further search was made of the premises occupied by one of the McDonald daughters, who was married, and further stolen articles found in her possession....

Previous to this I had contact with the McDonald family as a result of locating a stolen car in their garage...[13]

No one at the house knew anything about the car, and none of the MacDonalds were arrested as receivers of stolen goods by reason of the fact that Maggie MacDonald and two of her minor children appeared as Crown witnesses against Jack Cosgrave at his trial in Preston.

On December 15, 1935, Donald John MacDonald, aged 28, legally married Margaret Holland, a strikingly beautiful 19-year-old girl. In the following months, Margaret — usually as “Mary Wilson” — was charged twice with keeping a disorderly house (a euphemism of the law for keeping a house of prostitution), charged once with vagrancy, and once with public drunkenness. “Kitty Cat,” as Margaret became known on the streets, had a Depression-era job as a prostitute, while Mickey, having borrowed $200 from a bookmaker named Cecil Clancy, tried briefly to make a living as a bookie himself.[14] He soon gave that up and went back to being a thief. A comment on the marriage might be that Kitty tried to commit suicide in October 1936. Maggie MacDonald promised in Toronto Police Court that she would look after her daughter-in-law. “She had some trouble,” Maggie told Magistrate Cowan. According to a story, the trouble was Mickey, who hadn’t quit his philandering ways.

Early on the morning of December 3, 1936, Mickey and Kitty, likely both drunk, were perambulating along Queen Street East near Carlaw Avenue when Kitty chanced to admire some apparel in the window of Pearl Trimball’s Riverdale Ladies Wear. Mickey impetuously decided to show Kitty how easy a “kickin” really was. The police of the nearby Pape Avenue Station arrived in short order, to find the thief still in the store, with 14 overcoats and 3 dresses piled up by a door.[15] Charged with shopbreaking and let out on a $10,000 bond, Mickey promptly absconded bail. He made for Windsor, Ontario, and his friends of the 1920s. There, on January 30, 1937, Mickey, Dolly Quinton, and another man were drinking beer in the tap room of the British-American Hotel with their coats on hangers behind them when someone noticed a revolver showing from a pocket of one of the coats. Windsor detectives soon after arrested all three suspects, since all denied owning the guilty coat. Mickey, who gave the name John Ross of 121 Main Street, Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, later flew into an angry “you-don’t-have-to-do-this-to-me” rage at one of the arresting officers and, as part of this, volunteered that the gun-heavy coat was his. The detective’s account of this before Magistrate D.M. Brodie in Windsor Police Court got Mickey a conviction for possession of a revolver without a permit — and a sentence of two years in Kingston. Plainly, as the magistrate said in court, Mickey’s having had too much to say was the reason for his conviction.

Mickey McDonald and wife, Margaret “Kitty Cat” MacDonald (she was always MacDonald), circa 1935–37. This photograph appeared in the late edition of the Telegram of February 24, 1939, the day after Mickey and his brother Alex were charged with the murder of Jimmy Windsor. (York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections, Toronto Telegram fonds, ASC07405)

Mickey entering Kingston on April 3, 1937. (Library and Archives Canada)

Back in Toronto, on March 24, 1937, a County Court jury found Mickey guilty of the December 3 shopbreaking, after which Judge James Parker kindly awarded him two years, concurrent with the Windsor sentence. Judge Parker was impressed with Mickey’s fine manners in court and with the fact that, afterwards, he insisted on shaking hands with each member of the jury.