Читать книгу Plane Queer - Phil Tiemeyer - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER TWO • The Cold War Gender Order

The airplane’s success as a piece of military hardware during World War II had a profound impact on postwar civil aviation, stimulating immense growth for the industry. Wartime output included vast supplies of the airlines’ favored DC-3 aircraft, modestly modified for military purposes, which became a major workhorse for deploying troops and replenishing supplies across Europe and the Pacific. When the war ended, the military decommissioned many of these planes, selling them at discount prices to a variety of airlines and charter services, some of them founded before the war and others entirely new start-ups. This glut of newly available seats helps to explain the jump in air passengers after the war. U.S. airlines in 1941 had carried roughly five million passengers. Despite the decline of commercial air travel during the war itself, fifteen million people flew in 1946, and almost fifty-five million did so by 1958. Thus, by the close of the 1950s, air travel had expanded more than ten times over levels at the end of the 1930s.1 A new era of mass air transportation had begun, with airlines now competing with trains and ships for a larger chunk of the traveling public.

As an expanded airline culture consolidated in tandem with the economic and geopolitical order of the cold war, the flight attendant culture changed radically as well. But it did so in response to two countervailing impulses regarding gender in the aftermath of World War II. One impulse was to reward men, especially those who fought in the armed forces, with well-paying, unionized jobs that would remain lifelong careers.2 Consistent with these norms, various airlines—not just Pan Am and Eastern—welcomed men into the flight attendant corps after the war. And as victories at the bargaining table were won by newly organized flight attendant labor unions, the profession actually became slightly more male and better paid, at least in the immediate postwar years. Indeed, many of the stewards hired in these years stayed in their jobs for decades (in some cases into the 1980s), as their jobs offered stable wages, solid health coverage, lucrative travel benefits, and supposedly secure retirement pensions.

But a stronger and ultimately more lasting employment trend pulled the demographics of the profession in a very different direction, toward becoming an almost exclusively female domain by the close of the 1950s. While seemingly contradictory, this dynamic was also a consequence of white men’s growing privileges in middle-class and unionized jobs after the war, and it was coupled with the war-induced longing for a return to more traditional gender roles for men and women. As historian Elaine Tyler May points out, marriage and child rearing ticked upwards for almost two decades after the war, and white middle-class women were increasingly expected to seek fulfillment in tending to family needs at home rather than seeking out careers.3 That said, May also notes that women’s employment did not decline in the postwar years. Instead, the types of work women undertook changed, mainly for the worse. Gone were the stable and high-paying factory jobs of the war years, the ones valorized by the fictitious but compelling image of the strong and independent Rosie the Riveter. Instead, women entered workplaces that ostensibly complemented their primary roles as wives and mothers. Such work was poorly paid and overwhelmingly part time or temporary. Full-time working women typically held such jobs only in the years between high school and marriage.

In workplaces geared toward these younger women—with airline stewardessing a prime example—employees were expected to provide precisely the type of emotional work required of good wives and mothers. Serving meals and drinks, looking after sick passengers, soothing the nerves of worn-out businessmen, and changing dirty diapers—all done with boundless charm and alluring feminine beauty—made the stewardess’s role an ideal proving ground for marriage and motherhood. The stewardess had become a counterversion of Rosie the Riveter for the 1950s, an image of white feminine strength and working prowess that mainly reinforced a woman’s conformity to the traditional roles of wife and mother and did not challenge the male privileges of higher wages and stable long-term careers.

The image of the cold war–era stewardess is so emblazoned on the historical memory—one need only peruse films and television shows about these years—that it is easy to overlook how her status was briefly challenged by the paradigm of a male-privileged flight attendant corps.4 In this chapter, I retrieve this overlooked reality, examining how and why the stewardess, thanks to a combination of economic and cultural factors, ultimately became predominant in this profession. In doing so, I help nuance the customary understanding of the gender-based labor market retrenchment after World War II that focuses on the banishment of female laborers back to the home. Considering the plight of stewards helps isolate distinct groups of employees who languished under the cold war gender order: not only working women, who remained underpaid and shut out of notionally male careers, but also white men who attempted to maintain a foothold in service-oriented workplaces. Men who aspired to be stewards, like women seeking work in male-dominated professions, faced increasing likelihood of rejection as the 1950s progressed and, as we shall see, also risked greater derision as gender failures and suspected homosexuals.

Certainly, female flight attendants were also victimized by this corporate-imposed gender segregation. The successes of unionizing and collective bargaining, which bore fruit immediately after the war, were increasingly neutralized over time, thanks in part to stewardesses’ lack of clout tied to their gender. The airlines never revived the prewar practice of hiring skilled nurses as flight attendants, replacing them instead with women who possessed no health or safety qualifications and whose most valued assets were their youth, good looks, and charm. Additionally, they found ways to ensure that stewardesses would not accrue significant seniority, which would have allowed them to command the higher wages and more lucrative benefits that longer-serving stewards enjoyed. Most gallingly, many airlines added new mandatory retirement ages on top of the marriage bans that already existed back in the 1930s. American Airlines started this trend in 1953, followed by Northwest in 1956 and TWA in 1957; each of these airlines now forced stewardesses to retire at the still-sprightly age of thirty-two or thirty-five.5 Stewardesses were part of a familiar trope in American corporate practice: as in many low-skill professions, employers sought to feminize their workforces so as to enjoy greater leeway in keeping these jobs short term and low paying.

Stewards, meanwhile, also faced discrimination as the years progressed. By 1958 both Pan Am and Eastern had completely reversed their prewar policies of hiring only men and instead refused to accept them for such jobs. Thereafter, only a small New York–based airline, Trans Caribbean, which flew primarily between New York and San Juan, hired men as stewards, while TWA and Northwest hired a limited number of male pursers for their international routes throughout the 1960s. Another exception was United’s small cadre of Hawaiian men, who, starting in 1950, served as both flight attendants and cultural ambassadors on flights from the mainland United States to Honolulu. By and large, however, male flight attendants by the 1960s had virtually disappeared from domestic flights. They also were heftily outnumbered and put in supervisory positions requiring less interaction with passengers on U.S. carriers’ international flights.

All the while, stewards and male applicants for the job faced an even more virulent form of homophobia than had existed in the 1930s. As gay historian John D’Emilio notes, World War II amounted to a national “coming out” experience for gays and lesbians.6 The gender segregation and increased mobility during the war years helped bolster the size of gay and lesbian communities around the country, while simultaneously elevating straight society’s awareness of homosexuals. In response to this increasing sexual fluidity, U.S. society largely chose to clamp down, creating a variety of novel legal and extralegal mechanisms to stigmatize homosexuality. Stewards were again castigated as effeminate men, even more than their predecessors before the war. And gay stewards, who by the 1950s represented a sizable percentage of the male flight attendant corps, endured an extra dose of suspicion. Far from being auxiliary to the economic factors I discuss, the more virulent homophobia of the 1950s played an equally important role in making the career less amenable to men as the decade progressed. I consider homophobia and the flight attendant corps explicitly in chapter 3, after first examining here how financial and gender-based cultural pressures coalesced to nearly banish the steward from the job.

RE-MANNING THE FLIGHT ATTENDANT CORPS

In the immediate postwar moment, airlines, like most other employers in the country, felt obliged to reward veterans by accommodating them in the workforce. The flight attendant corps was not immune from this trend, especially at Pan Am and Eastern. Both airlines claimed during the war that their companies’ first female flight attendants had been hired to relieve men for war duty, so there was strong pressure to rehire the men once they were decommissioned. This sense of obligation pertained first and foremost to former employees, and Eastern was gearing up for a potential logistical nightmare in late 1945. As chief executive Eddie Rickenbacker noted, “There will be approximately 1,200 men returned from the Armed Services. The majority will want to come back and we want to be in position to absorb them in a manner that will be beneficial to them and the company.”7 The company further committed itself to new hires, even offering work to one thousand wounded veterans, who might otherwise face tremendous difficulty finding a job.8

The overall effect of these veteran-friendly employment policies, while certainly noble in intent, was to place many women at a disadvantage in the application process. Priority given to male veterans meant that well-qualified women were overlooked. Rickenbacker codified female applicants’ secondary status in a 1947 conversation with managers: “Don’t hire women unless you have to, but if you do hire women, hire women with brains. There are plenty of middle-aged women who have obligations and responsibilities, who want to do a good job, and there you will find the answer to some of your problems.”9 His words contradict themselves, as he accepts that the abilities of certain women will benefit the company in crucial ways but nonetheless tells his managers to place their applications at the bottom of the stack. Executives like Rickenbacker were willing to forego workplace efficiency in order to prioritize men over women.

The flight attendant corps was one of the positions at Eastern and other airlines that saw such favoritism for white men. Aviation historian Robert Serling claims that Rickenbacker briefly imposed an “edict banning the hiring of any more women as replacements for departing stewardesses,” which in turn led to higher percentages of men in the flight attendant corps by 1950.10 But thanks to the rapid increase in seating capacity after the war, all airlines, including Eastern, continued to hire stewardesses. Starting in January 1946, men reappeared at Eastern’s flight attendant training school, with many partaking in a retraining program established for former stewards who had served in the military. Photos of the first reintegrated class show that women outnumbered men by a 3-to-1 margin in a class of fifty, but this ratio evened out over the next few years as decommissioning progressed.11 Pan Am by the end of 1946 had a flight attendant corps that was roughly half male and half female and was training more men than women, at least in its Atlantic Division, which serviced its newly opened routes between New York and Europe.12 Even as late as February 1951, Pan Am’s graduating class in the Latin American Division included seven women and five men.

However, 1951 also exposed the considerable downside of men’s privileged status as soldiers and veterans. Even as Pan Am’s corporate newsletter celebrated the new class of flight attendants that February, it also noted that this mixed-gender makeup could soon end. The reason was that men’s availability for work was thrown into doubt by the military’s unanticipated engagement in Korea. It noted that “the five newest stewards...probably will be the last men hired for this job until the international situation clears.”13 Indeed, another man who applied at the Seattle base just a few months later discovered that Pan Am was not hiring men at all. Despite a strong personal interview and extensive experience as a steward on charter airlines, applicant Jay Koren was told, “We don’t anticipate the Ivory Tower giving us the go-ahead to hire [men] until the fall.”14 The Ivory Tower—Pan Am’s New York headquarters high up in the Chrysler Building—did, however, rescind the no-males directive later in 1951. Once conflict on the front lines in Korea had stalemated by early 1951, the labor market at home stabilized as well. Now confident that the military would not require all able-bodied men, Pan Am hired Koren and several other stewards.

The pre-1951 moment represented perhaps the most expanded hiring of male flight attendants before the 1970s. Not only were Pan Am and Eastern hiring again, but several other airlines started doing so for the first time. On the one hand, this was a response to the national priority to hire more veterans, but, like Eddie Rickenbacker’s decision to hire stewards with the advent of the DC-3 in 1936, it also reflected a desire to establish a more patriarchal order in the plane’s cabin. The first generation of post–World War II airplanes doubled passenger capacity once again, and the work of flight attendants was getting more complex and hierarchical. The DC-4, DC-6, Boeing Stratocruiser, and Lockheed Constellation all seated more than fifty passengers; therefore, there were now as many as four flight attendants serving passengers on any given flight. The response of several airlines was to create a new rank in the flight attendant corps, the purser, who delegated responsibilities to the other attendants. Pursers also handled communications with the cockpit and relieved pilots of some paperwork duties, which were also becoming more demanding. On international flights, they processed customs forms and interacted with border officials.15 They also earned significantly more money: a 40 percent premium over the regular flight attendant salary at Pan Am.16

This high-paying supervisory position was just the veneer of male privilege that some airlines needed to hire men. Seizing on the Truman administration’s efforts to increase competition on international air routes, a series of U.S. airlines were finally able to challenge Pan Am with flights to South America, Asia, and Europe. TWA, Northwest, and Braniff all appointed men to serve as pursers, and reserved this position for men only, once their international flights began. Delta Air Lines also introduced male pursers in 1946, despite being only a domestic carrier. Thus, between 1946 and 1949, a whole new male-only set of jobs was created, even at airlines that had never hired stewards.17

Eastern also created a purser position after the war and reserved it exclusively for men. In addition to getting basic training in safety and hospitality, men learned about personnel management and paperwork, while women increasingly were trained in hygiene and beauty. Despite the airline’s attempts in the 1930s to market its stewards as handsome and desirable, the glamour aspect of the job was now female only. Male trainees were exempt from exercises like this one described in its corporate magazine: “Each Saturday during the training course the stewardess trainees attend Dorothy Gray’s salon on Fifth Avenue where they are coached by experts on intelligent make-up, hair-do, speech and posture—a ‘charm’ course that would cost the private client $25.”18 Placing men automatically in the position of purser meant that they were better paid and held authority over the rest of the flight attendant crew, even over women with considerably more seniority. This hierarchical imbalance was also expressed in the plane’s cabin, where the men remained in the galleys for much of the flight. According to new company policy, “A Purser will prepare the food and a Stewardess will serve.”19

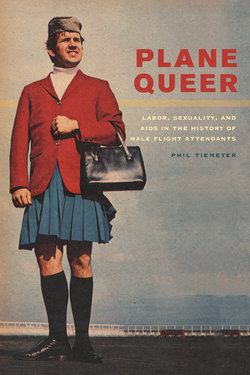

The steward’s new status as manly and militarized was perfected by a drastic uniform change from the 1930s (figure 7). Gone was the white double-breasted, form-fitting coat that had made the steward a fashionable presence. Also gone were the ginger-bread red piping and the bow tie, both of which had markedly divorced the earlier uniform from its military roots. Instead, the May 1946 innovations remilitarized the steward, as he was now outfitted from head to toe in navy blue, with gold piping on the hat and a gold star and stripe on the sleeve designating his rank (one of each, rather than the head pilot’s four). The steward was now virtually indistinguishable from the pilot—or a soldier in his dress uniform. Eastern’s public relations described this new uniform with the lackluster adjectives neat and business-like.20 There was no attempt to glamorize the steward, as the airline had done in the 1930s and continued to do with its charm school–trained stewardesses. The uniform instead emphasized a militaristic form of manliness, highlighting the steward’s role as a leader in the cabin. While perhaps consistent with the cold war militaristic ethos, this uniform choice was, as we shall see, out of sync with airlines’ attempts to make air travel more appealing to new female and children customers.

MALE PRIVILEGE AND UNIONIZING

In tandem with airlines’ embrace of the steward came moves to upgrade the profession into a secure, middle-class livelihood. Male flight attendants benefited disproportionately from the first contracts negotiated by newly organized flight attendant labor unions that led to wage increases, better health benefits, and retirement pensions. These moves were consistent with larger economic priorities promoted by New Deal Democrats and supported by the Eisenhower administration at the dawn of the cold war. Many industries emulated the status quo that took hold in America’s burgeoning armaments industries: in exchange for lucrative subsidies to contractors, the federal government established the expectation that companies would pay their workers a family wage and allow union representation to guarantee this. In turn, union leaders, especially those at the United Auto Workers (UAW) and the International Association of Machinists (IAM), used their increasing influence to help unionize workers in a wider swath of industries beyond those tied directly to the military-industrial complex. For flight attendants, the money and know-how for organizing came primarily from preexisting unions within the American Federation of Labor (AFL), especially from the pilots’ union, the Air Line Pilots Association (ALPA). Starting with United’s stewardesses in August 1945, flight attendants at airlines across the country (save for those at Delta) quickly unionized, becoming members of ALPA’s newly formed Air Line Stewards and Stewardess Association (ALSSA). Only Pan Am’s flight attendants opted for the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO)-affiliated Transportation Workers Union (TWU).21

FIGURE 7. Eastern’s first pursers, 1946, in pilot-inspired military uniforms. Great Silver Fleet News, July-August 1946, 35. Courtesy Eastern Air Lines.

Both the ALSSA and the TWU had immediate success at the bargaining table, securing substantial raises for employees in every pay grade. But flight attendants with greater seniority and those who ascended to the purser position were the biggest winners under these contracts. Male stewards were overrepresented in both of these categories, since they were unaffected by the airlines’ marriage and age restrictions on stewardesses and could easily—even automatically at some airlines—become pursers. For those promoted to purser, unionizing bestowed a twofold benefit: they enjoyed the across-the-board increases shared by others, plus a promotion into the even higher-paying category. Pan Am’s Miami-based TWU Local 500 was so proud of its first flight attendant contract in late 1946 that it boasted to all the airline’s rank and file, even the mechanics: “During your lunch or smoke period try to visit with some of the Flight Stewards or Stewardesses. Ask them how the CIO tackled the problem of wages AND reclassifications. Fully 118 (or some 36% of Flight Service) Flight Stewards and Stewardesses, shortly after their contract was signed, were immediately reclassified into Pursers with an average $72 per month increase.”22 Male flight attendants throughout the industry were enjoying similar double raises, especially since airlines reserved the new purser position for their male personnel.

Back in the 1930s, female flight attendants cost the airlines more than men in the same position. With the job’s relatively low wages that were equal for both men and women, the primary cost difference stemmed from stewardesses’ being forced out of the job when they married, thereby leading airlines to pay an additional $1,000 to train a replacement. But the rise of contracts negotiated through collective bargaining, coupled with the adoption of the purser category, changed the airlines’ financial calculations. The new pay scales meant that airlines were paying their veteran pursers quite a bit more than junior flight attendants, often for work that was only negligibly different.23 New employee training was still expensive, and airlines still deemed the rapid turnover of stewardesses to be a financial drain; however, the cost of long-serving flight attendants had increased considerably.

Men who entered the job and gained seniority were now commanding a family wage. In addition, they also garnered extra pension payments, greater scheduling autonomy, and increased sick leave, all of which altered the gender-based financial calculus for airline executives. By the mid-1950s, Captain Rickenbacker’s concern from the 1930s that women were too costly had flipped; men now were far more expensive. Cold war economic and gender expectations were coalescing to create an imbalance in the flight attendant corps: stewards now enjoyed a middle-class income and a potentially lifelong career, while stewardesses faced sexist work rules that forced them out when they married or reached their midthirties.

DOMESTICATING MILITARY HARDWARE

On the whole, stewards after World War II benefited from the militarization of U.S. society. They earned priority in hiring because of their status as veterans, and they gained disproportionately from the larger trend toward unionization that accompanied the cold war economic cooperation between government and private industry. Yet in other crucial ways they suffered from the entwinement of aviation with the militarism of the day. Following the work of historian Elaine Tyler May, it is important to recall that cold war militarism had a strong cultural counterbalance: a desire to downplay, even ignore, the existential threats to American security by embracing traditional gender roles and an idealized home life. May argues that “cold war ideology and the domestic revival [were] two sides of the same coin: postwar Americans’ intense need to feel liberated from the past and secure in the future.”24 Indeed, middle-class Americans effectively hid the geopolitical anxieties of the 1950s behind a curtain of domestic bliss; the nation’s muscular foreign policy was balanced—at least psychologically—by a feminine domestic sphere. A similar balancing of masculine and feminine was required by airlines in the postwar moment, especially as their quest for profits increasingly required them to diversify their clientele. This need ultimately left the steward in a vulnerable position vis-à-vis the stewardess.

To appeal to women and children, airlines needed to find a way to play down the militarized connotations of the airplane itself. Airplanes have always been a product of intense cooperation between the military and private industry. Before the war, a vast majority of planes were purchased by the U.S. military, as would also be the case after World War II.25 However, commercial airliners and military aircraft advanced in tandem during the prewar years, since aviation research and development were shared via a common governmental agency. Innovations that might have been developed as part of a government contract (more powerful engines, lighter-weight fuselages, etc.) were quickly adopted in commercial aircraft. At times, airlines such as Pan Am—not the U.S. military—spearheaded the advance of aviation technology. When hostilities broke out in late 1941, Pan Am acquiesced to the military’s lease of its largest and most advanced aircraft, the oversized Pan Am Clippers, since the military possessed nothing of the sort. Likewise, Douglas Aircraft simply modified its DC-3 to create the backbone of Allied military aircraft during World War II, the C-47 transport plane.

The war, however, radically reworked this relationship between military and commercial aviation. In the lead-up to World War II, the aircraft industry changed drastically. Military aircraft output soared, from roughly 2,000 planes in 1939 to 18,466 in 1941, finally peaking at over 96,300 in 1944.26 Aircraft manufacturers also devoted their research and development almost exclusively to the military’s fleet, which became far more technologically advanced than that of the airlines. Manufacturers produced impressive technological innovations in a very short period of time. Boeing’s B-29 Superfortress bomber became the new mammoth of the skies, boasting enough cargo capacity to carry an atomic bomb (as it did, in August 1945). It also was one of the first planes with a pressurized cabin, an innovation that finally allowed cruising altitudes in excess of ten thousand feet without oxygen masks.

Perhaps the most radical invention of the war years was the jet engine, which debuted in 1944. While still too novel to be of practical use during the war itself, jet technology—which ultimately tripled the speeds even of transport planes—became the cornerstone of military aviation development throughout the late 1940s and 1950s. It was military aircraft, not civilian carriers, that first possessed this awe-inspiring technology and heralded the onset of the “jet age” that captured Americans’ imagination. While some military inventions like pressurized cabins were quickly introduced into commercial use (1946), the jet engine remained military-only technology in the United States until 1958. This lag between military and civilian use firmly established that airplanes were now primarily products of the armaments industry. Throughout the cold war, aviation research and development depended primarily on the consortium of congressmen, military generals, and manufacturing executives that dominated the military-industrial complex.

Furthermore, as previously noted, airlines experienced yet another adjustment thanks to military decommissioning after World War II: a sudden glut of transport planes that the military offered at cut-rate prices. While the airlines possessed 397 aircraft at the war’s end, another 5,000 transport planes converted from military use, mostly C-47s, soon entered the civilian market.27 This sudden and dramatic increase in seat inventory forced the airlines to radically alter their business plans, leaving them little choice but to attract new customers. Aviation innovators like Juan Trippe of Pan Am embraced the new oversupply and introduced new pricing schemes, including a cheaper, less luxurious coach class and even more economical night flights. Trippe believed that his company’s future lay in democratizing access to air travel: “Air transport has the very clear choice of becoming a luxury service to carry the well-to-do at high prices—or to carry the average man at what he can afford to pay. Pan American has chosen the latter course.”28

These novelties led airlines to evolve from a solely elitist mode of transport to a product appealing to different types of customers with different price points. Of course, for most middle-class Americans, Trippe’s promise still rang hollow: the “average man” still found air travel prohibitively expensive—or a once-in-a-lifetime indulgence—until after deregulation in 1979. However, even in the 1950s, airlines were instituting multitiered pricing schemes and also gained approval from the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB, the government-run board that set prices for the industry) to engage in cut-throat pricing on a few select routes. Thus even cash-strapped economic migrants from Puerto Rico became consumers of air travel, since a San Juan–to–New York air ticket was now cheaper than passage by boat. They thereby became the first wave of economic migrants in history to arrive in the mainland United States by plane.29 New York’s newest airport, Idlewild (later renamed Kennedy), opened in 1948 and soon became an Ellis Island of the jet age.

In addition to democratizing air travel in key ways, airlines continued their efforts from the 1930s to attract more women and children. While businessmen remained the airlines’ core passengers, their spouses and families were increasingly coveted as a secondary revenue stream. Thus the postwar airlines sought to reinforce the proclivities of wealthier Americans to travel, especially fostering a passion for summer vacationing, while also expanding interest in the more customary winter sojourns to Florida or Cuba. Convention travel for spouses boomed, the airlines and other boosters began marketing hot climates like Florida for summer travel, and trips to Europe became status symbols for America’s growing upper and middle classes. A significant sum of these newly available travel dollars—by-products of America’s cold war prosperity—flowed from women (or at least spending choices they initiated) to the airlines.

Yet just as in the 1930s women and children first had to be convinced that air travel was safe and comfortable. The airplane’s role in World War II and Korea as military weaponry made this sales job more challenging. Potential customers were regaled with stories of pilots’ heroics from these wars, Hollywood films replete with dogfights and ghastly crashes, and news reports of the first combat missions for jet planes over Korea. The situation was exacerbated on August 7, 1955, when Boeing executives showed off their prototype of the 707 commercial airliner to a delegation of airline executives. Test pilot Alvin “Tex” Johnston, unbeknownst to Boeing personnel, had decided to send the plane into a barrel roll during the test flight. The sight of the first passenger jet plane flying upside down was an instant media hit, replayed often on television and reproduced in newspapers throughout the country. Yet, as much as this vision of adventuring masculinity and overpowering technology wowed the public, it also caused many to wonder whether commercial jet travel would be safe and comfortable.30 With former military heroes in the cockpit and jet engines perched under the wings, commercial aircraft by the late 1950s risked alienating customers by virtue of associations with the dangers and the heroic maneuvers of combat.

Airlines effectively had to conceal their machines’ muscular engineering potential (no more barrel rolls) and instead disguise them as cozy, warm spaces akin to the family living room. Designers thus sought to create a symbiosis between masculine and feminine elements, compensating for an exterior that projected mechanical power with an interior that was excessively luxurious and comfortable. If the plane’s technology and all-veteran pilot corps evoked militarism, then the cabin would have to evoke both domestic tranquillity and femininity.

Ads such as that shown in figure 8, from National Airlines in 1956, do more than place cute little girls and sharply dressed women in the fold of appropriate airline passengers. They also rewrite the relationship between technological innovation and masculinity. The cozy plane, with relaxed passengers sitting cross-legged in plush seats, even allows a fragile little girl to harmlessly saunter down the aisle—thanks to the technological innovation of radar. The plane is now a cross section of white America: young and old, male and female, all relaxed and enjoying the sight of the little girl as though sharing a joyful moment in a communal living room. Now that the DC-7 aircraft can detect turbulent air pockets by a radar system embedded in its nose, the little girl can roam the plane as freely as she would her own home. In the process, a piece of military hardware, the radar-guided plane, has become domesticated. The ad’s text affirms that the technology is actually feminine, as it christens the DC-7 the “Smoothest Sweetheart in the Sky,” thereby merging the identity of the mammoth aircraft with the fragile little girl. And hovering over this grand living room is the stewardess, playing ersatz mother to the little girl and doting hostess to the adults. She, too, along with the plane’s new technology, plays a vital role in feminizing the plane’s persona.

FIGURE 8. A 1956 National Airlines advertisement, reprinted in National Airlines, Annual Report, 1956. National Airlines Archives, folder “Archer, Bill: National Airlines Annual Reports, etc.” 1990-385, Historical Museum of South Florida, Miami, FL. Courtesy HistoryMiami.

Since flight attendants were the most obvious way to gender the cabin as a feminine domain, it became increasingly imperative for the airlines to hire women over men. In this sense, then, the cold war had profound consequences for stewards and stewardesses. It made stewards undesirable on account of their failure to embody domesticated femininity and to attract women and children as customers. Stewardesses’ work, meanwhile, increasingly resembled that of women at home rather than that of nurses or qualified safety professionals. As the airlines’ passenger base became more feminized—women went from 25 percent of passengers before the war to 33 percent by the end of the 1950s—so too did the flight attendant corps.31 The steward in his military-style navy uniform now seemed strikingly out of place.

GROUNDING THE STEWARD

In retrospect, the comments of Eastern CEO Rickenbacker from the first staff meeting after flight attendants unionized were prophetic. He bemoaned to managers: “You have had an election recently of your stewards and stewardesses. Why, I do not know, but I do know there are a lot of smart guys taking advantage of a lot of suckers.... They are going to ask for ungodly things—they want this and that—but maybe some day they are going to wake up without anything at all, because you can’t get blood out of a turnip.”32 Indeed, in the decade after unionization, Rickenbacker and his fellow airline executives found various ways to keep the career low paying despite collective bargaining. For most men, this meant Rickenbacker’s words were spot-on: they ended up “without anything at all.”

The first steps toward the complete feminization of the job came when Delta quickly reversed its efforts to introduce male pursers. The airline ceased hiring men by 1949, just a few years into the new policy, after reportedly hiring “a maximum of 19 men... at the height of the experiment.”33 Meanwhile, Eastern responded to its rising labor costs in two main ways, both of which adversely affected male flight attendants. First, the airline dispensed with the purser role in the mid-1950s, eliminating the automatic seniority boost and pay bonus that men had enjoyed. Then, from 1954 through 1957, the airline first scaled back, then completely ceased its hiring of stewards. Economics were a key factor in this choice; increased competition from both Delta and Florida-based National Airlines on the lucrative New York–Miami route spurred the airline to improve its service and cut its labor costs by employing more women. By then, executives could cite claims from customers and public relations representatives that stewardesses rendered more effective customer service.

Some airlines with international routes did retain pursers and even continued to hire only men for these positions into the 1960s. Northwest, Braniff, and TWA adopted this policy, choosing to absorb the higher costs of male pursers in an effort to keep a male-dominated hierarchy in their plane cabins. In fact, TWA remained so wedded to this policy that they went to court in New York State in the late 1960s to keep their pursers all male.34 This placed the airline in an unusual position: they asserted that only men had the necessary qualifications to be pursers, while simultaneously claiming, along with other U.S. carriers, that only women were capable of being regular flight attendants.

Pan Am, meanwhile, forged a mixed stance that was at once progressive and regressive. Alone among international carriers, it always offered women an equal opportunity to become pursers, granting them unique access to higher-paying, more senior positions. Coupling this with its policy allowing women to fly without any retirement age—even if they were married—the airline created an admirable model of relative gender equality in some realms. Yet the carrier also continued to fire women once they became pregnant and enforced strict weight standards that forced many of them out of the workplace. Likewise, men encountered discriminatory attempts to lower labor costs; by 1958 Pan Am had stopped hiring men altogether and ultimately became the defendant who wronged Celio Diaz.

The airlines may have victimized stewards in the most draconian way, but stewardesses encountered a complex web of newly entrenched indignities. Airlines gained a newfound appreciation for stewardesses who married young and thereby cut short their careers. One Braniff recruiting manual even encouraged stewardesses to see quick marriages as a perk: “Where do Braniff Hostesses Go When They Leave Us? You guessed it... most of them turn in their wings to get married! The romantic statistics say 98%!”35 Similarly, Eastern Air Lines, reversing Rickenbacker’s earlier disdain for stewardesses who married, now saw this fact as a tolerable annoyance. The airline resigned itself to constantly hiring new flight attendants, noting matter-of-factly: “With larger planes, expanded routes, and the fact that 36 per cent of the Stewardesses resign each year to marry, the company is always on the scout for new talent.”36 The newly created age restrictions placed on stewardesses had a similar effect: forcing women out of the job before they accrued significant seniority and replacing them with younger, lower-paid personnel. Thus the prohibition on new male hires and the age and marriage restrictions placed on women need to be considered together as complementary attempts to circumvent the costs of collective bargaining.

These policies served their purpose well. The unions were unable to overturn the marriage bans and age restrictions on stewardesses. They also could not counteract Eastern’s and Pan Am’s decisions to stop hiring stewards, which affected only job applicants, not employees. Finally, union leaders were at a loss about whether to defend purser positions, especially at those airlines like Eastern, Northwest, Braniff, and TWA, where the job category drove a wedge between male and female members. By and large, then, the unions had to satisfy themselves with pyrrhic victories. They could boast to their rank and file that they had negotiated higher wages and better pension benefits. But given that these benefits accrued mainly through seniority, the average stewardess—whose career lasted about eighteen months—never benefited from these achievements. Both male applicants for the job and stewardesses facing age, weight, and marriage restrictions were in a “holding pattern,” awaiting the 1964 Civil Rights Act to combat the various forms of sex-based discrimination they encountered.

MILITARY-INDUSTRIAL COMPLEXITIES AND THE STEWARD

Under the cold war military-industrial complex, an oligarchy essentially controlled the economic choices of a vast swath of the U.S. economy.37 Significant authority went to those most centrally tied to the armaments industry, whether politicians, military brass, or industry executives. Unquestionably, though, their decisions had both economic and social ripple effects throughout society. The airlines were just one step removed from the military-industrial complex’s epicenter. Like the military, they were customers of Boeing, Lockheed, Douglas, and the other aircraft manufacturers. And they were just as dependent on aeronautical innovations—jet planes, pressurized cabins, more effective radar systems—as those defending the nation.

It makes sense, then, that developments in the cold war affected all levels of the airline industry, even influencing the seemingly apolitical choice of whether flight attendants should be men or women. Economically, the sudden glut of decommissioned aircraft hardened airlines’ resolve to both increase their passenger base and cut labor costs. Stewardesses, airline executives soon realized, enhanced both of these prospects. They didn’t have the male-privileged economic clout of stewards, who could make a long-term career of the job, often in higher-paying purser roles. Meanwhile, stewardesses also could emulate the doting mothers and living room hostesses of the 1950s American home (who, like stewardesses, were denied a fair wage for their labor). As such, stewardesses were an inexpensive domesticating touch. They reassured new customers that a trip on an airplane—otherwise a converted piece of military hardware piloted, in most cases, by war veterans—would be safe, comfortable, and even enjoyable, and they did so for a fraction of the wages of long-serving stewards.

Both stewardesses and stewards found themselves trapped by increasingly rigid cold war gender norms. Stewardesses couldn’t escape the increasing erasure of memories of the war years, when women had been paid the same salary as men and had successfully performed the same work. Meanwhile, stewards rode a wave of male privilege that rose up, then fell apart—at least for them—by the mid-1950s. Their ascendancy immediately after the war entailed a manly makeover: gone were the debonair uniforms of the 1930s, replaced by military dress that put the steward on par (visually, at least) with a pilot or soldier. Unionization in the war’s aftermath also bestowed a solid, middle-class wage upon the steward. Yet none of these benefits lasted, save for those who had secured these jobs before almost all the airlines stopped hiring men by the late 1950s. Instead, these enhanced male privileges simply led stewards to become prohibitively expensive. The airlines exploited the rigid gender norms and, as we shall see, the rampant homophobia of the decade to segregate the airplane into two distinct realms: the cockpit, a place that belonged to manly, well-paid pilots, and the cabin, a serene space where services were provided by doting women who had no claim to a family wage.

While stewards’ ultimate expulsion from the airlines industry is well accounted for by the economic machinations discussed in this chapter, there is more to the story. I turn next to the joint cultural forces of sexism and homophobia that also helped to eliminate their jobs.