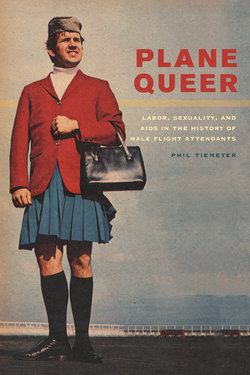

Читать книгу Plane Queer - Phil Tiemeyer - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

The idea for this book came to me back in 2004, while I was sifting through a box of materials in the Pan American Airways Archives at the University of Miami. Among the archives’ vast collection of papers, I found dozens of folders, enough to fill an entire box, marked “Stewardesses.” One folder in this box jumped out at me: a relatively thin one marked “Stewards,” whose contents, though not extensive, were fascinating. I first noticed newspaper clippings from the late 1960s, which spoke of a court case filed by a young Miami man named Celio Diaz Jr. Diaz invoked the clause of the 1964 Civil Rights Act that forbade “sex discrimination” when Pan Am refused to hire him, or any other man, as a flight attendant. He thereby began a legal assault on the corporate sphere’s gender norms, one complemented by far more numerous efforts from female plaintiffs. Hundreds of women were fighting at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and in federal courts to gain access to higher-paying male-dominated professions, while Diaz and a few dozen other men demanded entry into female-only service sector jobs.

When Diaz finally won his case in 1971, a new era for flight attendants was born: not only Pan Am but all other U.S. airlines were forced to integrate men into their flight service crews. This was a little-known, highly controversial consequence of the landmark civil rights legislation passed in 1964. A clipping from the Wall Street Journal cast the ruling as an affront to America’s heterosexual, male-privileged hierarchy that kept flight attendants young, female, and attractive: “To the extent male stewards replace glamorous stewardesses,” the Journal scornfully mused, “the [Diaz] case ... may prove to be one of the more controversial interpretations of the 1964 law among members of the male-dominated Congress.”1

Deeper in the folder, I found much older photographs of Pan Am’s first flight crews from the 1920s and ’30s. Interestingly, the entire crew were men: pilots, copilots, and stewards. It turns out that this most storied of U.S. airlines didn’t hire a single stewardess until the labor shortage of World War II, and it continued to hire stewards in sizable numbers well into the 1950s. Only in 1958 did Pan Am switch to the female-only hiring policy that Diaz successfully challenged a decade later. The same was true of another of America’s great legacy carriers, Eastern Air Lines, which imitated Pan Am by introducing all-male flight crews in 1936 and continuing to hire a sizable number of stewards until the mid-1950s.

Once again, the photos were remnants of a history I had never heard before: I was unaware that male flight attendants had been in the career even before stewardesses, the first of whom had started in 1930, a couple years after Pan Am’s first steward. This small folder’s contents held tremendous promise to uncover a seemingly forgotten history, chronicling how one group of men struggled to maintain their foothold in a profession that gradually went from being originally male, to almost exclusively female, to sexually integrated by the 1970s.

Excited by my discoveries, I walked into the office of Dr. Craig Likness, then the university’s head archivist, to discuss the folder on stewards. I told him how men seemed to have played a key role in various moments of the career and turned to him plaintively for more records. Surely this material was rich enough to warrant more folders—or, ideally, boxes—on stewards. First came the bad news: Craig was familiar enough with the collection to know that everything explicitly about stewards was in the meager folder. Then came the good news: he too was fascinated by my findings, both what they revealed and the promise of all the things they concealed. “Well, it sounds like you’ve found a great book topic,” he smilingly concluded.

From that day onwards, with the help of devoted archivists and patient former flight attendants who sat for hours of interviews, I have been cobbling together the history of the male flight attendant. Though far from exhaustive, this book reconstructs the key contours of this history, all the while demonstrating how male flight attendants have held a broader significance beyond aviation history. The fact that these men have been treated as gender misfits and suspected homosexuals since their debut makes them an important case study of gender discrimination and homophobia in an American workplace. Plane Queer thereby offers nearly a century of civil rights history that typically has been overlooked, especially examining the various successes and setbacks flight attendants experienced in striving for queer equality in the United States.2

Thanks to social norms that took root in the early 1930s, the male flight attendant has stood out, as the book’s title suggests, as plainly queer for almost the full run of this profession. After all, these were white men who performed what large segments of U.S. society deemed servile “women’s work” or “colored work” and who thereby invited scrutiny as failed men and likely homosexuals. According to Kathleen Barry, whose book Femininity in Flight is the most authoritative history of the career to date, “The flight attendant occupation took permanent shape in the 1930s as ‘women’s work,’ that is, work not only predominately performed by women but also defined as embodying white, middle-class ideals of femininity.”3 The historical record confirms this finding, as stewards in the late 1930s constituted just one-third of the nation’s flight attendants. Thereafter, their numbers declined significantly, receding to a mere 4 percent when Diaz v. Pan Am was being argued in the late 1960s.4

Yet a countervailing fact is also true: men have persisted in this career from its first day to the present, often in surprisingly large numbers. Indeed, their status as men that society perceived as queer—a good many of whom also self-identified as gay—who were also unionized, working-class employees in a relatively high-profile, public relations-oriented profession makes them particularly important historical actors in a larger struggle to combat sexism and homophobia in the American workplace.

Male flight attendants’ contributions to queer equality developed in an ever-widening spiral, as they quietly sought acceptance first from fellow flight attendants and other coworkers, then from airline managers and union officials, and then—in the most far-reaching examples—in groundbreaking legal fights that influenced the larger trajectory of gender-based and sexuality-based civil rights in the United States. Plane Queer uncovers these moments when male flight attendants successfully expanded civil rights, focusing especially on Diaz v. Pan Am, legal actions filed by flight attendants to protect the work rights of people with HIV/AIDS, and the gradual bestowal of domestic partner benefits and other “gay-friendly” workplace rules that arose in the 1990s.5

At the same time, I also focus on moments of retreat, when sexism and homophobia prevailed over queer equality, as when Pan Am and Eastern stopped hiring stewards in the late 1950s. Equally devastating for men in the career was the AIDS crisis of the 1980s, when various airlines exploited public panic to ground flight attendants with HIV/AIDS, even when medical experts dismissed the potential of such employees to endanger passengers’ health and safety. In particular, Air Canada flight attendant Gaëtan Dugas, known more often by his media-imposed alias “Patient Zero,” demonstrated the potential of male flight attendants to elicit fear and anger at this panicked time. Despite a distinct lack of proof, gay journalist Randy Shilts succeeded in planting the idea among readers of his 1987 book And the Band Played On that this attractive, gay, unabashedly promiscuous flight attendant was the origin of America’s AIDS epidemic.6 Shilts interlaced accounts of “Patient Zero” throughout his 630-page tome on the early history of AIDS, all the while promoting the salacious theory that Dugas was responsible for the virus’s entry into the United States and its initial spread from coast to coast.

While queer flight attendants today enjoy fuller equality than they did in the 1950s or 1980s, their accomplishments are still in jeopardy. At first glance, the benefit parity that airlines offer to gay, lesbian, and even transgender workers is impressive, including domestic partner health care coverage and travel benefits. At the same time, however, these same employers over the past decade have dramatically reduced wages and benefits, often using court-protected bankruptcy proceedings to rewrite labor contracts to the disadvantage of workers. Thus the expansion of benefits to queer employees has occurred in a climate that increasingly deprives all flight attendants—female and male, straight and gay, gender conforming and otherwise—of the financial means necessary to secure a middle-class standard of living. Consequently, the quest for queer equality that flight attendants have undertaken through the last eighty-plus years of commercial flight has been fraught with ups and downs and today is in a nosedive (to use a graphic aviation metaphor), propelled by the neoliberal economic pull of lower ticket prices at the expense of workers’ livelihoods.

I am not the first to write of flight attendants’ contributions to the U.S. civil rights legacy. In fact, I hope readers will examine my work alongside accounts by Kathleen Barry and Georgia Panter Nielsen.7 These scholars have accentuated how this career became an important locus of “pink-collar” labor and activism, where stewardesses fought against work rules that kept them underpaid and oversexualized. Indeed, stewardesses were among the first women to flood the EEOC with sex-based discrimination complaints once the 1964 Civil Rights Act came into effect, and their legal efforts helped to professionalize this career and many other female-dominated workplaces. Quite reasonably, stewards are neglected in these histories, since they never endured the same indignities: rigorous weight checks, forced retirement upon marrying or reaching age thirty-two, pregnancy bans, and employer-sanctioned sexual harassment.8

Yet these preexisting histories thereby overlook the full extent of discrimination faced by flight attendants, including stewards’ virtual banishment from the job at midcentury and increased scrutiny during the AIDS crisis. Recovering these additional experiences highlights how gender nonconformists and homosexuals endured pernicious inequality of their own (alongside that faced by the young, attractive, gender-conforming stewardess corps) and fought just as vigorously to overcome it. Often, queer rights and disability rights are deemed auxiliary pieces to America’s civil rights legacy, which primarily foregrounds race-based struggles and women’s rights efforts. By recovering the steward’s neglected history dating back to the 1920s, we find that homophobia has been intimately entwined (and just as enduring) as sexism and that AIDS phobia, while more recent, has been just as intense.

Like Barry’s Femininity in Flight, my work also occasionally follows flight attendants’ struggles for equality beyond the workplace and into venues such as labor union deliberations, congressional records, EEOC proceedings, and courtroom arguments. Plane Queer highlights previously overlooked chapters in legal history that pertain to the plight for queer equality, from the rise of the “homosexual panic” defense (used in 1954 at the expense of an Eastern Air Lines steward named William Simpson), to the entanglement of homophobia with sex-based civil rights in the wake of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and onward to the fight for equal workplace rights for people with HIV/AIDS.9

Legal scholars to this day treat Diaz v. Pan Am as a groundbreaking interpretation in gender discrimination law, since it forced greater scrutiny on employers’ decisions to hire only one gender of employees for a certain job. But less familiar, even to many of these scholars, is Diaz’s standing as one of the first and most successful gender discrimination cases brought by a man. While the mainstream media and right-wing commentators during the Diaz trial ridiculed the notion of male gender discrimination as a bizarre misappropriation of the law, some feminist legal scholars were intrigued. In particular, future Supreme Court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who headed the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project in the early 1970s, began to argue more cases on behalf of male plaintiffs. She envisioned a new and ultimately only partially accomplished legal goal: removing all government support for sexual stereotypes, whether for women undertaking notionally male roles or men like Diaz aspiring to notionally female roles.10 Plane Queer thus offers a unique rendering of feminist legal history, which gains new texture by foregrounding male flight attendants and other similarly situated men.

Just as male flight attendants’ history deepens our understanding of civil rights and legal history, so too does it complement previous scholarship on the origins of America’s gay subculture. These histories have detailed the genesis of a gay community in realms as diverse as the medical world, homophile activist circles, federal government policy, and, perhaps most importantly, the nightlife in industrialized U.S. cities.11 The case of male flight attendants and their contributions to gay society suggests a new and as yet overlooked venue for gay community building: the workplace.12 For gay flight attendants (and the passengers who suspected their stewards of being gay), the aisles and galleys of airplanes, as well as crew hotels and crash pads, served the same role that other gays and lesbians found in bars: a place where they could meet others like themselves and even embrace their same-sex desires for the first time.

This fact suggests a secondary meaning for the book’s title: much as gay men forged a foothold in cities’ bohemian scenes, they appropriated the airplane as a space where they belonged and secretly thrived. Planes—one of America’s cherished symbols of progress and modernity—acquired a gay presence, thanks especially to the stewards who worked in them. In other words, stewards made the plane queer. The book proceeds from the fact that a sizable cadre of gay men worked in the skies to their gradual agitation for queer equality. In this way, this workplace follows a script that queer historians have noted in the gay nightlife circles that cautiously prospered in postwar America: numerous individuals’ ostensibly apolitical motive of seeking out a place to belong ended up creating communities that could increasingly function as power bases in the fight for queer equality.13

Connected with reflections on flight attendants’ contributions to gay life in America are two common sets of questions posed about my topic: Just how gay has the male flight attendant corps been through the years? And how and why did the profession get to be so gay? These are difficult questions to tackle. For one, there has never been a formalized effort to count gay or straight airline employees. After all, such figures are not required under federal or local employment laws and are not easily attained without infringing on workers’ civil liberties. That said, I found that some gay flight attendants in various decades involved themselves in gossip aimed at discerning their coworkers’ sexuality. Likewise, others I interviewed were quite willing to estimate the percentage of gays they worked with. According to their conclusions, between 30 and 50 percent of male flight attendants were gay in the 1950s, and between 50 and 90 percent in the 1970s. Speculation on today’s corps of gay flight attendants tends closer to 50 percent, with lesbian and transgendered colleagues being a small but more prevalent contingent than ever before. Sometimes, too, as at Pan Am’s San Francisco base in the 1950s, straight stewards took it upon themselves to make lists of gay flight attendants in the hopes that management would then weed out the men they uncovered. Such efforts were unsuccessful, however, as Pan Am’s managers refused to act on these complaints.

A more successful, though less empirical, way to address these questions is to follow the line that historian Allen Bérubé developed in his work on queer ship stewards. His understanding of how and why certain careers become gay identified stresses the relationship between sexual identity and regimes governing gender and race in the workplace. Ship stewards, like airline stewards, performed work that was notionally feminine, primarily undertaking servile tasks to comfort customers. One ship official, when asked why his company hired so many gay men, simply replied, “If it wasn’t for these boys, who else would we get to do this kind of women’s work.”14 Yet as Bérubé aptly adds, men of color could also credibly perform such work in trains, hotels, and wealthy homes without raising suspicions of queerness. Indeed, the work that the all-male corps of African American railroad porters performed was quite similar to air and ship stewards’ work, though porters never developed a reputation as gay.

Only when white men undertook such work did it become a noticeably queer job. Thus the air steward’s gayness—presumed for all stewards and true for a good many of them—relied on U.S. airlines’ racist hiring policies that largely remained in effect until after the 1964 Civil Rights Act. For several decades, no member of the flight crew at any airline could be African American or another racial minority, except for light-skinned Latinos whom Pan Am hired for their Latin American Division or Hawaiian-born stewards hired by United for their Honolulu flights after 1950. The result, as Bérubé states of ship stewards, was that “white gay men on the liners learned to racialize gay as white.”15 Simply stated, queer careers arose out of America’s Jim Crow past. It took a series of exclusionary choices based on both gender and race for white men like flight attendants to stand out as gay. Indeed, for these men to become plainly queer, they first had to enter workplaces that were notionally feminine and predominantly white. When this career became queer is thus something we can pinpoint, even without knowing the details of how stewards identified sexually: it occurred in the very first decade of U.S. commercial aviation—in the 1930s—when stewardesses began to outnumber stewards and African American applicants were uniformly turned away.

The chapters of this book detail the undulations of tolerance and discrimination experienced by male flight attendants from the dawn of commercial aviation in the late 1920s through the post-AIDS crisis years of the late 1990s and 2000s.

The development of the career shows that these men experienced sexism and homophobia as fluid, ever-changing variables. At certain times, male flight attendants—and, more specifically, gay male flight attendants—enjoyed a modicum of tolerance from the public and their coworkers. At other times, the animosity they faced threatened their livelihoods. While we might think that queer equality developed in history along a progressive trajectory, starting with very little traction in the earliest years and gaining increasing momentum as time went by, this is not the case. The deeper reality is that each decade has experienced a tenuous interplay between progress and regression. Even in ostensibly homophobic decades like the 1950s, flight attendants made impressive strides toward forging a gay-tolerant career. Yet at the very same time male flight attendants risked becoming objects of ridicule for segments of society that pushed back against such gains. Thus flight attendants’ hard-won achievements toward gaining tolerance were rarely ever decisive, and even their most stellar victories, such as the Diaz court case, often were tinged with regressive characteristics as well.

Chapter 1 considers the late 1920s through the beginning of World War II. These years were the de facto heyday of stewards, even as stewardesses gradually became established as the preferred employees for this job. The 1930s saw varied reactions to stewards, from tolerance and even playfully campy portrayals of stewards as dapper fashion icons to deeply phobic responses to these seemingly unmanly men. In trying to explain this variety of responses, I place early aviation within its upper-class social milieu: the “gay” (in the sense of over-the-top and fun) nightlife of Prohibition-era cities. Since the airlines drew their customers from the cosmopolitan elite who frequented this opulent and flirtatiously androgynous nightlife, Pan Am and Eastern enjoyed greater freedom to hire stewards and promote them as dapper and sexually desirable. But especially as World War II loomed on the horizon a deeper discomfort with stewards surfaced, including the first evidence in the media and from airline archives that stewards fostered homophobic derision and animosity.

Chapter 2 is the first of two chapters that examine the steward’s demise in the post-World War II era. This chapter focuses on the economic rationale behind the steward’s expulsion, linking it to the cold war’s military-industrial complex that took hold after the war. In the immediate postwar era, civil aviation settled into a second-class status versus military aviation in terms of aircraft development and supply. The airlines inherited thousands of decommissioned military planes, creating a vast oversupply of aircraft that altered their financial strategies considerably, forcing every airline to become more cost-efficient. I argue that stewards were the indirect casualties, “collateral damage,” if you will, of this militarization of the industry. The oversupply of aircraft brought on by the war meant that stewards, with their higher salaries and longer tenures, were now less cost-effective than stewardesses. By reshaping the flight attendant corps as female only, postwar airlines realized significant payroll savings. The more the career was treated as women’s work, the less the airlines had to pay flight attendants. Airlines were then also free to impose egregious work rules on stewardesses that men would never be expected to tolerate, including marriage bans and forced retirement in their mid-thirties.

Chapter 3 examines a related social development, the rise of homophobia in the postwar era, which also led to the steward’s demise by the close of the 1950s. As normative models of American manhood increasingly embodied the ruggedness and adventuring of a soldier, stewards raised more eyebrows as failed men. In the early 1950s, insinuations against stewards circulated not only in rumor mills but also in salacious front-page headlines. Miami’s newspapers took the lead, sensationalizing a gay sex tryst gone wrong: the murder in 1954 of an Eastern Air Lines steward, William Simpson, at the hands of two young male hustlers on a lovers’ lane. The antigay hysteria in Miami following the murder solidified the link between gender transgression (men doing women’s work) and sexual perversion, and it portrayed stewards as threats to normalcy and decency. In this climate, pressure grew on Eastern and Pan Am—both with strong ties to the Miami market—to stop hiring stewards. The career, seemingly, had become irretrievably feminized and the stewards too tied to homosexuality in the public’s eyes. This homophobic stance was also adopted in the legal world, as the jury for the Simpson case acquiesced to the defense’s claims of “homosexual panic” and refused to find his killers guilty of first-degree murder. This legal argument, effectively refuting gay men’s standing as equal under the law, serves as important background for the civil rights legal discussions in the ensuing chapters.

Chapter 4 describes the social shock waves generated by the return of male flight attendants to the job after Celio Diaz successfully used the 1964 Civil Rights Act to reverse the airlines’ female-only hiring practices. Diaz’s legacy, though virtually unknown today, attests to queer Americans’ deep investment in the civil rights moment of the 1960s, even though they were often seen as unwelcome in this movement. While many citizens were increasingly ready in the 1960s to extend legal equality to African Americans, they were far more reluctant to extend the same guarantees to women. Meanwhile, the idea of extending equality to homosexuals or gender nonconformists like male flight attendants was typically greeted with alarm. Incidents like the Simpson murder just a decade earlier had conditioned many to believe that gays and lesbians had no claim to equality, regardless of how neutrally the laws themselves were written. The awkward legal standing of queers becomes evident as the chapter traces the entanglements of Celio Diaz and male flight attendants with civil rights law from the dawn of the 1964 Civil Rights Act to the final decision in Diaz v. Pan Am.

In this light, I treat the Diaz case as a vitally important precursor to future queer equality victories. Even though Diaz himself wasn’t gay, his victory in the courts helped establish limits on social conservatives’ use of homophobia to block gender-based civil rights and prevent the inclusion of gays and lesbians into mainstream civil society. Of course, Diaz’s victory also opened the doors for countless numbers of gay men to enter a relatively high-paying, unionized, and public relations-oriented career. The flight attendant corps would become a new sort of workplace by the 1970s, increasingly responsive not only to women’s rights but also to queer rights.

Chapter 5 examines the flight attendant corps of the 1970s, paying particular attention to how the workplace changed with this new influx of gay men. With thirty-five years of hindsight since first hiring a man, a former member of American Airlines’ hiring committee nowadays identifies a deeper import to the post-Diaz flight attendant corps: “The collision of women’s liberation and the outing of sexuality created an explosion that changed the airline industry beyond recognition.”16 To a certain degree, the whole of American society experienced a similar explosion in the 1970s, the heyday of women’s liberation and maturation period of gay rights. But because the flight attendant corps was disproportionately female and gay male, it experienced this culture shock much sooner and more acutely than the rest of U.S. society. Flight attendants were in the avant-garde of this major social upheaval. This chapter covers this “explosion” in greater detail, examining how women and gays cooperated—and sometimes fought—in both the workplace and the union hall to find common ground that respected all employees: male or female, straight or gay.

I also link these developments with the considerable backlash against a feminist, progay ethic, whether from airline executives or larger conservative social movements. These increasingly severe skirmishes in the culture war also influenced the legal legacy of Diaz v. Pan Am, as conservatives continued to portray women’s rights initiatives like the Equal Rights Amendment as backdoor pathways for queers to gain equal rights. Meanwhile, as progressives like Ruth Bader Ginsburg made male plaintiffs key to her legal strategy in the 1970s, others increasingly bemoaned such support for men as misguided and counterproductive. By the close of the decade, Diaz risked being orphaned even by champions of women’s rights and gay rights.

Chapter 6 begins to examine the most heart-wrenching, darkest days of the flight attendant corps. All of the flight attendants I interviewed regard AIDS as a deeply personal tragedy that took from them coworkers and dear friends. The workplace was filled with talk—though most of it still hushed—of funerals, extended sick leaves, new therapies, and the occasional hopeful signs of recovery. Tears still well up in many of my interviewees over a decade after the worst of the dying has ended. “AIDS was devastating for us,” was the common refrain.17 Male flight attendants also became more acutely aware than other workers of how AIDS was a political, not just a personal, tragedy. After all, their careers were being threatened both by the epidemic’s health dimensions and by the political response of conservatives seeking to use AIDS as a bludgeon against gay civil rights. The demonization of Air Canada steward Gaëtan Dugas, better known as “Patient Zero,” illustrates the ways that flight attendants became embroiled in these pitched social battles over AIDS. This chapter details the facts of Dugas’s life and the state of the “Patient Zero” myth circa 1984, before Shilts circulated the myth in his book.

I also chronicle the plight of another flight attendant with AIDS, whose legacy—while less known—warrants equal attention. United Airlines flight attendant Gär Traynor was also diagnosed with AIDS very early in the crisis. But his response to his diagnosis ultimately offered a more positive basis for overcoming AIDS phobia. When his employer, citing passengers’ and coworkers’ fears of contagion, permanently grounded him in June 1983, Traynor and his union fought back. In a key 1984 legal victory, Traynor became one of the first people with AIDS (PWAs) in the United States to win the right to return to work, a precedent that was replicated in subsequent court decisions and in the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act.

Chapter 7 traces these two rival legacies regarding AIDS and flight attendants—Dugas’s castigation as a scapegoat and Traynor’s role as an advocate combating marginalization—into the 1990s. The chapter begins with the 1987 release of Randy Shilts’s book And the Band Played On and his portrayal of Dugas as the origin of the epidemic in America. My analysis confirms long-standing assertions by scholars and AIDS activists that Gaëtan Dugas was not the first American with AIDS.18 Instead, Shilts’s editor, Michael Denneny, confirmed to me that Shilts manipulated the “Patient Zero” narrative to garner media publicity for the book. Denneny claims that the subsequent media frenzy saved And the Band Played On from obscurity, vaulting it onto the best-seller list. With so much attention focused on Dugas, flight attendants—though they certainly did not ask for such a role—were now implicated in the larger social and political battles over AIDS, post-Stonewall gay sexual practices, and workplace rights for PWAs. Flight attendants and their employers were more passive actors than Shilts, social conservatives, and AIDS activists in this fight, but they helped determine whether PWAs would be quarantined out of the public sphere.

Indeed, the airlines ultimately helped to defuse the hysteria embodied by “Patient Zero.” Just months after Shilts released his salacious account, United Airlines finally stopped its long-established practice of grounding flight attendants with AIDS. And by 1993, American Airlines was working hard to overcome its previous AIDS-phobic and homophobic reputation to become the United States’ first self-proclaimed “gay-friendly” airline. Such practices didn’t completely dispel the indignation directed at Gaëtan Dugas and his fellow male flight attendants, but it did decisively marginalize social conservatives, at least in the corporate boardroom and in corporately administered public spaces like airplanes. Airlines like American and United had rather abruptly switched allegiances in the culture war, even as AIDS hysteria was still potent.

Chapter 8 examines the increasingly gay-friendly era of aviation since the 1990s, during the peak of America’s neoliberal economic policies. Gay and lesbian flight attendants won more benefits as the 1990s progressed, including flight privileges for their domestic partners and, by 2001, health benefits for partners. While such developments seem to make the 1990s the ideal conclusion to the topsy-turvy history of male flight attendants and their encounters with homophobia, they are not as one-dimensionally optimistic. Indeed, following work of other queer scholars, I explain how expanding gay civil rights via the private sector is fraught with danger.19 Just as gay flight attendants have attained parity with their straight peers, all of them have endured unprecedented pay cuts and the loss of collective bargaining power. Along these lines, I consider the plight of disgruntled JetBlue flight attendant Steven Slater, who became an instant celebrity in 2010 when he walked off his job by deploying the plane’s emergency slide and sauntering across the JFK Airport tarmac toward his waiting car. Slater embodies how male flight attendants, even if they are no longer discriminated for being gay or HIV positive, nonetheless experience their work as undignified and underpaid in the cutthroat economic age of deregulation, airline bankruptcies, and court-monitored reorganizations.

The conclusion summarizes my findings on the quest for queer equality in the eighty-plus-year career of the male flight attendant. It especially focuses on this fact: while these men have always stood out as plainly queer in the long expanse of commercial aviation history, the intensity of the animus directed against them has shifted considerably through the years. Certain decades stand out as particularly sexist and/or homophobic, while others have been more tolerant. These undulations, I conclude, are consequences of deeper economic and legal factors. Sexism and homophobia became most pronounced when there was economic gain to be had by marginalizing these men. Similarly, tolerance predominated when the airlines stood to benefit from treating these men well. All of these financial calculations took place amid a similarly evolving legal landscape; the expansion of civil rights laws tended to alter the financial calculus of discrimination to stewards’ benefit, while legal innovations like “homosexual panic” had the opposite effect.

Overall, this investigation of a queer workplace exposes how sexism and homophobia are undergirded by deeper economic and legal developments. It is not enough to countenance male flight attendants as just plain queer; they are also people with fluid legal standing and evolving economic value. Recounting the history of male flight attendants and the quest for queer equality allows us to consider these multiple factors—queerness, economics, and the law—in tandem, arguably even more effectively than in the ways queer community histories have been written to date.