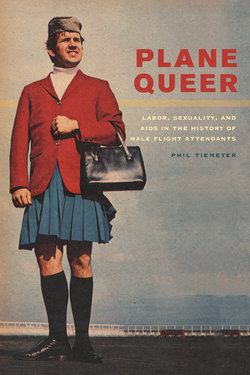

Читать книгу Plane Queer - Phil Tiemeyer - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE • The Pre–World War II “Gay” Flight Attendant

From histories of the flight attendant profession it would be easy to come away with the notion that America’s first flight attendant was a woman. Many accounts describe how a savvy Iowa nurse, Ellen Church, approached executives at Boeing Air Transport (the predecessor of United Airlines) in 1930 and prevailed on them to usher in a new female member of their flight crews who would keep passengers comfortable and assist them in emergencies. Far fewer accounts mention that such jobs actually existed before Church and that men, not women, held them. Pan Am’s inaugural flight between Key West and Havana on January 16, 1928, could be just as immortalized in flight attendant histories as Church’s first flight over two years later. An artist’s rendering of the 1928 flight (figure 1) shows the airline’s very first flight attendant, a nineteen-year-old Cuban American named Amaury Sanchez, standing in his black-and-white uniform and greeting passengers as they board the Fokker F-7 plane. While a few other men served before him, Sanchez was the first U.S. flight attendant on a so-called “legacy carrier,” and in that sense he represents the beginning of a line of men and women who would make their careers as airborne ambassadors of reassurance, charm, and service.1

Over time, however, Ellen Church’s hiring has been remembered and Sanchez’s almost entirely forgotten. After all, the more familiar understanding of the profession as female dominated begins with Church. Labor historian Kathleen Barry has correctly noted that the flight attendant career “took permanent shape in the 1930s as ‘women’s work.’”2 Certainly, by the 1950s, popular media like the Saturday Evening Post could matter-of-factly misreport the origins of the career: Ellen Church “was hired by United to work their flight between two Western cities, and to recruit other girls for similar duty. She did so and a profession was started.”3 Indeed, when Eddie Rickenbacker, then CEO of Eastern Air Lines, introduced his plans for a male-only flight attendant corps in late 1936, the Washington Post went so far as to belittle these men as “male hostesses,” suggesting they were interlopers in an already well-established female realm. “Capt. E. V. Rickenbacker confessed yesterday he is simmering in a nice kettle of fish,” the reporter noted, “because he proposes to install flight stewards or, if you prefer, male ‘hostesses’ on Eastern Air Lines planes.”4 In just half a decade, even as men like Sanchez still held all positions in Pan Am’s flight attendant corps, Eastern’s stewards were seen as gender misfits.

FIGURE 1. Artist John T. McCoy Jr.’s rendering of “Pan American’s first passenger flight-Key West, Florida, to Havana, Cuba, January 16, 1928-Fokker F-7,” 1963. Courtesy Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

Rickenbacker withstood these attacks, and significant numbers of men continued to take the job. In fact, Eastern maintained a male-only corps of flight attendants up until the labor shortage of World War II, and Pan Am did the same, from the time of Sanchez’s hiring until 1944. Thanks to these two airlines, men during the 1930s constituted around one-third of flight attendants.5 Thus, compared to the female-dominated fields of nursing or typing, where women in the 1930s held over 95 percent of positions, the flight attendant profession was still an extensively gender-integrated space.6 But these publicly disparaged “male hostesses” were clearly flying into cultural headwinds. As all-white or light-skinned Latino men performing servile work customarily reserved for women or men of color, they elicited deep anxieties surrounding the evolution of gender and sexuality norms in Jim Crow America.

It is anachronistic to speak of a “gay” flight attendant corps that endured “homophobia” in the 1930s. In those years, unlike the postwar years, homosexuality was a barely choate identity category. It found expression mainly in scientific tomes as a sexual pathology and in a rather limited urban nightlife that grew up alongside the other illicit pleasures of Prohibition-era America.7 In addition, explicit sources such as memoirs or corporate records on homosexuality in the steward corps do not exist, which means I have no ability to assess stewards’ actual sexual behaviors and attitudes.

To speak of “homophobia” is also, therefore, problematic. In fact, even if stewards’ sexual identities were known, it would be enormously difficult to discern when they experienced discrimination based on sexuality rather than gender. As these men walked the tenuous cultural line identified by Barry—and, more polemically, the Washington Post—that sought to cleanly divide male and female realms, we know they experienced discrimination that belittled these men as women. This cultural response is easily construed as homophobic, and I do, in fact, use the term in this manner.8 Yet such discrimination actually depended on the culture’s sexism that rigidly restricted male and female social roles. Similarly, the fact that the African American men performing the same servile tasks as Pullman porters on trains never elicited derision as “male hostesses” shows that such epithets depended on America’s racism as well.

My primary focus in this chapter is stewards’ unconventional gender performance in the 1930s. I especially scrutinize remnant public relations materials, assessing the degree that stewards were portrayed as either appropriately masculine or deficiently so. I also examine what links may have existed between the steward’s public image and the nascent gay (homosexual) subculture of the 1930s. The first half of this chapter examines the steward within his socioeconomic milieu, as an employee designed to appeal to the white, wealthy, cosmopolitan urban dwellers who made up the lion’s share of air travelers in the 1930s.9 These customers, who were predominantly men, had already acclimated themselves to what I call the “gay”—in quotation marks—lifestyle that arose in the Prohibition era, where opulence comingled with illegality and sexual adventure.10 While this social scene was not “gay” in a sense synonymous with “homosexual,” participants did embrace a softer version of masculinity that emphasized the pursuit of libidinal pleasure, and some homosexual encounters were tolerated, even if only a fraction of men chose to engage in them. While the steward could not aspire to participate fully in this eccentric lifestyle because of his working-class status, he was groomed by Pan Am’s and Eastern’s public relations departments to cater to this softer upper-class masculinity. In this sense, stewards of the day belonged—at least aesthetically, from an examination of their uniforms and other public relations materials—to the more fluid gender and sexuality norms that typified the “gay” life of the urban elite.

The second half of the chapter examines the first stirrings of homophobia (in the sense of a virulent sexism) directed at the steward. Interestingly, more than just external observers like the Washington Post journalist belittled stewards for their inadequate masculinity. Eastern’s and Pan Am’s own public relations materials betrayed a degree of apprehension that at times surpassed the Post’s. This section examines both an Eastern article on a steward’s “diaper drama” (changing a baby’s diaper in flight) and a violently demeaning comic published by Pan Am in their respective in-flight magazines. As indicated by the discomfort that even their employers displayed, stewards of the 1930s had undertaken a troubling social role, even if they were spared the more explicit homophobia of the postwar moment.

The chapter also details how technology played a vital role in casting the steward as a social outcast. Here my work relies heavily on previous historians, who have begun to stress the “mutual shaping” that occurs between technological and social innovation.11 In terms of gender, historians now realize that “the boundaries between how people designated male are expected to behave and how people designated female are expected to behave are sometimes redefined, negotiated, or violated” by technology.12 Regarding flight attendants, I add one important element to Kathleen Barry’s work stressing the feminization of the career in the 1930s: I show how new technology, when coupled with the culture’s sexism, helped render stewards ever more queer as the decade progressed.

The release in 1936 of the two most advanced pre-World War II aircraft—the DC-3, heralded as the first modern passenger aircraft, and the Pan American Clipper, the largest passenger plane to date—played a particularly important role in defining stewards as unmanly. These innovations allowed the airlines for the first time to credibly domesticate the cabin and assert this realm as decidedly feminine.13 Airplanes were now safe and comfortable, thereby permitting an influx of new female passengers and even children. With his work increasingly devoted to catering to customers as they reclined in spaces more evocative of their own living rooms, the steward seemed increasingly out of place. Technology was thus central to ostracizing this group of men, opening them to derision as laughable “male hostesses.”

“GAY” TAKES OFF

It was sheer coincidence that the 1920s marked both the rise of commercial aviation and one of the most formative moments for gay male communities. Yet the location of both these innovations in America’s largest cities increased the likelihood that they would become intertwined. As historian George Chauncey points out, the term gay held multiple meanings during this period. When referring to the lifestyle of America’s Prohibition-era elites, it connoted flamboyance, awareness of cultural fashion, fun, and transgressions that could be enjoyed by straights and gays alike. It also held strong overtones of illegality, because of patrons’ indulgence in alcohol and their dabblings in sexual vice, including renowned Broadway “pansy shows.”14 The sexual connotations of the term go back at least to the nineteenth century, when gay referred to female prostitutes and brothels. In the 1920s and 1930s, however, the term was innocent enough that a morally upstanding person could use it to express her enjoyment of a night out at the theater, but still edgy enough to suggest sexual illicitness.

For men in this upper-crust “gay” culture, traditional notions of masculinity were being reworked. Prohibition-era cosmopolitan men were expected to indulge in customarily feminine activities: they knew how to dress well, manicure themselves, and dance like Fred Astaire. Their social lives often revolved around Broadway shows, speakeasies, and, for some, brothels, all venues that tolerated more promiscuous heterosexual and/or same-sex desires. As Chauncey summarizes, these men lived in a “time when the culture of the speakeasies and the 1920s’ celebration of affluence and consumption...undermined conventional sources of masculine identity.”15

Note that these “gay” developments were affecting heterosexual men at the time, ostensibly having nothing to do with one’s sexual object choice. That said, homosexuals moved in the 1920s and 1930s to appropriate gay as a self-identifier, regardless of their class status. The more effeminate so-called “fairies” were the first to do so, since they more fully embodied the traits of fashionability, gender transgression, and emotional excess that the term denoted even in the larger culture. Thus, by the early 1930s, at least in major cities like New York, gay maintained two separate but closely related meanings. It was now synonymous with fairy but also retained a nonhomosexual meaning of frivolity, whose potential impact was to increase effeminacy in all men.16

The airlines saw an influx of “gay” culture from two different sources. First, the same wealthy patrons of the “gay” nightlife were also the airlines’ core customer base, which is hardly surprising given air travel’s status as a prohibitively expensive luxury in the 1930s. Only the very rich could afford to pay the significant premium over rail tickets. And only men were expected to be daring enough to fly on airplanes, much less be gainfully employed by the few corporations willing to pay for plane tickets. In addition to these wealthy cosmopolitan customers, Pan Am hired male flight attendants, who became “gay” icons themselves, because the airline proceeded to ensconce them in the style and opulence expected by the elite men they served. Following the example of other white male service professionals in cities—think of bellhops, doormen, ship stewards, and elevator attendants—Pan Am stewards became fashionable accessories catering to this elite, adorned in military-inspired suits, and changing into white sport coats and gloves when serving meals aboard planes.

Stewards’ fashionable dress and access to high-society clientele, even if they didn’t share their customers’ exalted class status, also probably drew envious attention from some in the “fairy” community. In his study of early twentieth-century gay erotica, art historian Thomas Waugh notes a particular fascination with men in service-related jobs. He asks rhetorically: “What to make of the recurring iconography of young men in service occupations such as bellhops?”17 Waugh is particularly struck by the contrast with post-World War II pornography. While this later material emphasizes more macho imagery, the prewar items tend to fetishize male softness. Something about a man’s servile softness stood out, to many “fairies” at least, as deeply homoerotic.

Ideas about male softness and homoeroticism aside, the work aboard airplanes in commercial aviation’s earliest years was a mixture of both notionally masculine and feminine tasks. For this reason, it would be inaccurate to see early stewards as transgressors into a decidedly feminized realm. Air transport until the mid-1930s was quite dangerous and downright unpleasant. One early customer on a twelve-passenger Ford tri-motor plane, one of the first planes large enough to accommodate a flight attendant, confessed: “When the day was over, my bones ached, and my whole nervous system was wearied from the noise, the constant droning of the propellers and exhaust in my face.”18 The cabins were not heated or air conditioned, nor were they soundproofed or pressurized. Vomiting was so prevalent that all passengers were furnished with “burp cups” akin to spittoons. Facing such unpleasantness while paying a premium over the cost of rail travel, early air passengers surely welcomed the added touch of a flight attendant to cater to their comfort. But airline executives were uncertain whether the hostile environment required a flight attendant with manly fortitude or the comforting touch of a woman.

Reflecting how this job rested atop America’s gender fault line, the initial flight attendant work descriptions, whether at Pan Am or at airlines like United that hired only women, were more varied than in later years. All flight attendants were expected to pitch in on notionally manly ground duties. As Inez Keller, an original stewardess at United in 1930, remembers, “We had to carry all of the luggage on board....Some of us had to join bucket brigades to help fuel the airplanes [and] we also helped pilots push planes into hangars.”19 Along these lines, Pan Am’s stewards also were responsible for rowing passengers ashore from their seaplanes (which the airline favored until after World War II), handling customs paperwork, and buying provisions in South American markets for the return flight.

Once everyone was on board, however, the job description was more tied to comforting passengers: after assigning seats, flight attendants passed out packages of cotton for the droning noise and chewing gum for the altitude shifts. They then served food, which in the earliest years was typically a boxed lunch of cold or steamed chicken. Other than that, as Pan Am’s first steward, Amaury Sanchez, noted, “My only instructions were to keep people happy and not too scared.”20 This rather open job description led flight attendants to improvise a great deal and undertake a wide variety of tasks that straddled the nebulous line between men’s work and women’s work: changing diapers, shining shoes, reassuring nervous flyers, or playing a quick game of gin rummy.

These service-oriented tasks drew far more attention from the airlines’ public relations departments than flight attendants’ safety roles or physically demanding work. This was especially true of the stewardesses, all of whom were required to have a nursing certificate to better prepare them to assist in emergencies. Yet any focus on nursing skills reinforced just how dangerous even routine air trips could be. Public relations departments therefore preferred to highlight stewardesses’ regard for passengers and their sexual availability. With an assist from Hollywood’s first of many stewardess movies, Air Hostess, in 1933, female flight attendants became associated with comfort and sexuality. The film’s advertising poster contained the provocative moniker, “She went up in the air for romance and thrills...”21

While Air Hostess marked the beginning of America’s decades-long and well-publicized heterosexual love affair with stewardesses, the flip side of this erotic fascination has so far remained undocumented: starting in 1933, stewards also were marketed as alluring sex objects. The fictitious public relations persona known as “Rodney the Smiling Steward” became the most famous male steward of the 1930s (figure 2).

FIGURE 2. “Rodney the Smiling Steward.” Pan American Airways Magazine, March 1933, 15. Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Miami Libraries, Coral Gables, FL.

The “Rodney” marketing campaign involved placing hundreds of life-sized, full-color cutouts of the steward in train stations and travel agencies all along the East Coast and as far west as Chicago. The goal of the promotion was the same as most airline marketing strategies through the 1950s: to lure the wealthy clientele of train and ship lines to Pan Am’s international air routes. But the use of a male steward as the company’s publicity ambassador would never again be replicated at Pan Am until after the 1970s, reflecting just how unique the steward’s moment of visibility was. Rodney’s short life span and his subsequent consignment to public relations obscurity both testify to his softer version of masculinity, which for a brief while in the 1930s enjoyed a higher degree of social acceptability among Pan Am’s wealthy prospective clientele.

The “Rodney” campaign accentuated the steward’s softer features, especially his dashing good looks and elegance when adorned in his formal black-and-white uniform with red highlights. With his smile and slightly cocked head, Rodney combined both youthful attractiveness and an approachability that invited people to size him up, thereby placing him in the notionally feminized role of alluring sex object. According to Pan Am’s corporate newsletter, Rodney had tremendous potency in this regard, at least in its own offices: “From all the comments, Rodney has made quite a hit....We thought he would, ever since the first day he was brought into the office for final inspection, suntanned, shoes shined, close-shaved and all, and the ladies deserted their typewriters to flock around.”22

Stewards shared these alluring physical qualities with other working-class men in the service industry, but their role as icons of style stood out against more widespread images of working-class masculinity: the exceptionally muscular images of white male factory workers and agricultural laborers (think of those popularized in WPA art), or the renderings of doting but safely asexual black train porters, busboys, and the like. The conflation of the steward’s white skin and his job’s fashionable servility drew him closer toward the aesthetic excesses of the dandified urban “fairies.” His suntan, dapper dress, and well-manicured face emulated those of the wealthy (largely heterosexual) playboys of high-society Midtown or Harlem speakeasies, while his class status placed him in a more passive role of serving other men and using his charm to accrue favor. A 1938 interview that Washington Post columnist Tom McCarthy conducted with Eastern Air Lines steward Bill Hutchison again emphasized these same characteristics seen in the “Rodney” campaign, highlighting the job’s emphasis on male physical beauty. “Besides having to pass rigid physical examinations,” the article notes of stewards, “they’ve got to watch their diet as closely as a movie star. When the needle on the weighing machine goes beyond 150 pounds they’re likely to have outgrown their job.” Coupled with this rigorous weight regimen came a preoccupation with suntanning: “What Bill was worrying about, particularly, when I saw him was not what he’d do when he got tired of being a flight steward, but rather what the March winds were going to do to his red and painful Florida sunburn.”23

Stewards’ white skin was an essential physical trait that reinforced their softness, or, if you will, their “gayness.” In the very train stations where Pan Am placed the life-sized Rodney cutouts, thousands of African American men held very similar jobs but never attained the status of sexualized public relations agents. Indeed, the railroads chose these men in part because of their supposed sexual undesirability. In his study of Pullman train porters, journalist and author Larry Tye notes that porters’ dark skin—when coupled with the predominant racism of the time—meant that “passengers could regard them as part of the furnishings rather than a mortal with likes, dislikes, and a memory.” This ability to effectively become “an invisible man” allowed porters intimate access to the sleeping quarters and changing rooms of white men and women.24 Thus, just as he never attained the status of a sex object, the Pullman porter also never became an ambassador of the newly crystallizing “gay” subculture that arose in America’s largest cities during the pre–World War II era.

The sexual history of stewards and stewardesses on planes was quite a different story. In their workplace, the primary object of 1930s sexual desire, white skin, was placed in arm’s length of the passenger. Since no airline hired African Americans as flight attendants until the civil rights era of the late 1950s, the entire career was dominated by white women and men.25 Stewardesses bore the brunt of this newly unleashed sexual desire. Many male passengers showered affection on these women and also sought out their company once the plane landed. A stewardess from 1939 noted, “You never have a trip that two or three or four men won’t ask you to dinner or a luncheon.”26 Hollywood only stoked the notion of stewardesses’ sexual availability. The famed actress Joan Bennett, who played a stewardess in the 1936 film Thirteen Hours by Air, enticed men by giving them advice on how to score a date with a real stewardess. Her words advanced a prevailing view and also exposed the galling willingness of the airlines to force their stewardesses into sexual roles: “If you ask her for a date,” commented Bennett, “she is obliged to say, ‘Yes, sir,’ and accept. It is a company rule on all airlines!”27

Nothing of the sort would be expected of male stewards, given deeply entrenched social codes that required men to initiate sexual advances with women and forced male-male sexual encounters to play out with furtive exchanged glances and the subterfuge of double entendres (including the term gay itself). Such codes ultimately made stewards much more difficult to deploy as erotic ambassadors for the airlines, just as stewardesses’ nursing skills were hard to market in delicate and appealing ways. Thus, in relatively short order, Rodney and other steward-centered public relations efforts were overshadowed by efforts from Hollywood, newspapers, and the airlines themselves to promote stewardesses as the most enchanting sexual newcomers of the decade. But that is not to say that the steward immediately disappeared as a public relations ambassador. Instead, his role simply became more limited. Meanwhile, with the rise of new aviation technology, these marketing attempts centering on stewards became even more suspect as “gay,” at times suggesting outright homoeroticism.

GREAT STRIDES IN TECHNOLOGY, GREAT MISGIVINGS ABOUT MASCULINITY

The year 1936 featured phenomenal advances in civilian air travel, empowered by significant innovations in aircraft technology. It saw the introduction of the world’s most successful (in terms of being the longest serving, safest, and most widespread) aircraft of the pre–World War II era: the Douglas Corporation’s DC-3. Indeed, the DC-3 dominated the skies for the next two decades, becoming the workhorse for the world’s major airlines well into the 1950s and serving as the preferred transport plane for the Allied militaries in World War II. An even grander plane debuted that same year: the Pan American Clipper (a seaplane originally manufactured by Sikorsky and later by Boeing), which boasted the largest payload and longest range of any civilian vessel. The Clipper was the world’s first flying behemoth and allowed Pan Am to initiate service all the way from San Francisco to China. The DC-3 and the Clipper could fly transcontinental or overseas routes, increasing flight times from just a couple hours in the air to full overnight trips. In fact, Pan Am’s record-long 2,400-mile nonstop flight from San Francisco to Honolulu would spend almost a full day in the air. These new planes also doubled capacity, accommodating at least twenty-one passengers each.

Air travel after 1936 was consequently a very different experience than before, for both passengers and flight attendants. Both of the latest aircraft offered passengers greater comforts, starting with a smoother ride, a climate-controlled environment, and a cabin with improved soundproofing. The lack of air pressure still required pilots to stay below a ten-thousand-foot ceiling, which made for a bumpy ride at times, but the aerodynamics of the DC-3 in particular (with its wings integrated in the body of the aircraft) significantly lessened the risk of accidents. Seeking to emulate the luxury of rail travel, the airlines commissioned top industrial designers like Raymond Loewy and Donald Deskey to outfit the new planes’ interiors. Passengers now enjoyed stylish and comfortable touches, including fancy sitting lounges with plush reclining seats, designated dining tables, sleeping chambers with bunks more spacious than those on trains, warm meals prepared in-flight, and movies projected on the front wall of the cabin.28 While still not a perfect emulation, airplane interiors increasingly invoked the opulence of ship or train interiors and permitted many of the creature comforts of one’s own home.

As historian David Courtwright notes, this move toward greater safety and comfort permitted the first significant diversification of airlines’ clientele. Airline marketing executives promoted their new planes as female-friendly and child-safe, hoping to cash in on their easiest growth demographic: wives and families of the wealthy businessmen who already were frequent flyers. After all, these potential customers enjoyed the same class status as their wealthy husbands and fathers, making them uniquely able to afford the airlines’ prohibitively expensive product. Thus airlines like United created a simple marketing strategy designed to appeal foremost to women: “Tell them how comfortable they’ll be, how delicious the meals are, how capable the stewardesses are, how luxurious their surroundings will be, and you can ‘sell’ women on air travel. Leave the ‘revolutions per minute’ to the men.”29

As this quote suggests, flight attendants’ jobs were increasingly tied to more feminine tasks like cooking and providing comfort to passengers. For the first time, stewards and stewardesses were expected to prepare full meals in flight, as both the DC-3 and the Clipper boasted galleys fully stocked with ovens and refrigerators. Meanwhile, the work of providing for passengers’ comfort also increased the potential for passengers and flight attendants to establish erotic ties, albeit in subtle ways. This increase in erotic potential may well have led more customers—over 75 percent of whom were men—to prefer stewardesses over stewards.30 After all, as airplanes approached the opulence of Pullman cars, flight attendants now might touch their passengers when passing them a pillow or tucking them under a blanket. Their gazes might also be palpable to passengers disrobing behind curtains in Pan Am’s or United’s sleeper cabins. Some first-time travelers’ raw nerves offered other opportunities for intimate touch. One steward noted in a 1938 Washington Post article that his gender actually benefited him in this regard, since a good number of these new fliers were women. He recounted that nervous female passengers often wanted him to hold their hands: “Now, I’d been instructed on how to make a nervous passenger feel at ease. But they never told me I ought to hold the lady’s hand.”31

At the same time, some aspects of these technological innovations actually made the flight attendant’s job stand out as more masculine. Most important in this regard, with passenger capacity now doubled and a myriad of new tasks the job became more complex and hierarchical. Two or three attendants now staffed flights, and their work roles were increasingly varied. Some executives like Eastern’s CEO Eddie Rickenbacker, the famed World War I fighting ace, found men to be the obvious choice for this more complex job. In October 1936 he made the decision to hire only men as flight attendants for the dawn of the DC-3 age, even though the company had hired only women a few years earlier.32 His reasoning was grounded in traditional sexism rather than some novel desire to promote gender transgression: “Women have shown themselves extremely heroic in emergencies. Nobody can take that away from them....But planes are getting bigger, there is more to do in them, and men are the logical answer.”33

This raw invocation of male privilege did not go unchallenged. In fact, Rickenbacker’s announcement placed his company—and the flight steward—in the heart of a public relations battle over gender and work. One Washington Post reporter referenced Rickenbacker’s World War I heroics to emphasize the magnitude of public displeasure, which, in his words, “promises to make his toughest battle with an enemy plane appear tame before this ‘steward vs. hostess’ war is over.”34 Yet the adversaries in this so-called “war” were more difficult to identify than the Post article made it seem. The reporter suggested that the discontent came from feminist circles. The headline stated that “feminists” were “aroused” by Eastern’s plan, while the article itself employed even more colorful language: “When Rickenbacker revealed his line was planning to add stewards, feminists lost no time in hopping on his weatherbeaten neck. What was the idea, they wanted to know, hiring men for work that women have proved they can do capably?” While the article certainly references a plausible feminist grievance, the reporter offers no names and fails to quote anyone espousing these views.

Eastern was quick to tamp down concerns about stewards by inviting First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, America’s most politically connected woman, who later became outspoken on feminist issues, aboard an early flight. According to Eastern’s in-house publication, the Great Silver Fleet News, Mrs. Roosevelt “comes right out and says what she thinks.” And in this case, stewards received her seal of approval: “The flight stewards,” she noted, “are most courteous and helpful.”35

Just as likely as a feminist critique of stewards is another possibility: that men who enjoyed being served by stewardesses were deeply upset with the airline’s decision. The same article suggesting feminists’ arousal actually was placed in the Post’s Section X, an addendum to the Sports section. Littered with college football scores and advertisements for men’s clothes, the section clearly had an overwhelmingly male readership. Moreover, the article’s cheeky tone is reminiscent of fraternity-house conversations, as it starts off with the previously quoted description of stewards as “male hostesses.” Thus, even before Eastern’s stewards made their inaugural voyage, other men were already ridiculing them for their perceived effeminacy.

Rickenbacker’s decision exposed a rift within male chauvinist circles. Despite invoking sexist reasoning for his male-only policy, Rickenbacker had alienated a demographic essential for the airline’s survival: the macho pilot corps and the unchaperoned businessmen who were his core customers. In this internecine war among chauvinists, Rickenbacker mixed economic reasons and aggressive bravado to defend his actions, always sidestepping the claim that stewards were failed men. At a closed-door meeting, facing a hostile crowd of his own pilots who wanted to know why he had changed the policy, Rickenbacker baldly replied, “Because you bastards are making enough dough to buy your own pussy!”36 And in reference to the laments of his core customer base of businessmen, he noted, in slightly less colorful terms, “If passengers want to fool around with girls, let ’em do it at their expense, not mine.”37

His comments, while flippant, expose an underlying economic reality behind the commodification of stewardesses’ bodies: selling female sex appeal could become prohibitively expensive for the airlines. Stewardesses actually commanded the same wage as men during the 1930s.38 This parity was unusual for the time, but it reflects the fact that these women held superior credentials in the form of their nursing degrees. All female flight attendants thus had completed at least two years of college and also held valuable skills in the case of a health emergency on board. Meanwhile, stewards at Pan Am and Eastern needed only to possess the equivalent of a high school degree and a few years’ experience in a customer service field like ship stewarding, bell-hopping, or waiting tables. “Even filling station attendants will not be overlooked in the search for personnel,” noted one article covering Rickenbacker’s choice of stewards.39

All told, stewardesses actually cost the airlines more on average than stewards. Rickenbacker bemoaned how his company, when it had hired stewardesses before 1934, had spent one thousand dollars training each employee, only to have them quickly get married and leave.40 Of course, he could have undone this problem by allowing married stewardesses to continue working, like his all-male pilot corps and even his stewards. But such thinking was seemingly beyond him and all other airline executives in the 1930s. Instead, Eastern embraced a male-privileged orthodoxy: “When a flight-steward marries he is more valuable to the company because his stability increases, whereas the stewardess who marries gains a husband and loses her job.”41

Because Eastern had very little competition on its most lucrative routes, Rickenbacker did not need to give his straight male customers (much less his pilots) the costly amenity of attractive stewardesses. Eastern competed with companies like American and Delta within the triangle connecting Chicago, New York, and Atlanta. However, its most lucrative route—the busy vacation and convention corridor between New York and Miami—remained an Eastern monopoly.42 Thus there was no pressing economic rationale for Rickenbacker to raise his costs by hiring stewardesses without the hope of increasing his revenue. The other major airline to hire men, Pan Am, similarly faced little competition before World War II. The airline’s primary destinations in the 1930s were in the Caribbean and South America, with the China route opening in late 1936. After having been awarded every contract with the U.S. Postal Service to carry mail to its destination countries, Pan Am was guaranteed to be the only U.S. airline that could make money on these routes. Meanwhile, competition from South American airlines was largely thwarted by Pan Am’s aggressive monopolistic practices.43

Overall, then, the dollars and cents of selling stewardesses as sexual icons broke down this way: domestic airlines facing more competition on their most lucrative routes hired stewardesses and were more likely to use them in their marketing. They did so even though the company might lose much of their thousand-dollar start-up investment in a stewardess if she married early. But both Eastern and Pan Am, which had a certain degree of protection from competition, chose the less fetishized stewards, thereby securing a flight attendant corps that would remain on the job longer than the average stewardess. The trade-off was that stewards’ customer appeal was more restricted to niche markets, including some travelers who preferred male employees and others—both female and male—who found stewards sexually desirable.

As to Eastern’s steward corps itself, two somewhat ironic caveats warrant attention. First, these stewards owed their jobs to a male chauvinist executive who was responding to the technological innovation of the DC-3 in a way that he felt would reinforce the patriarchal order of U.S. society, placing men in workplaces that were deemed complex and hierarchical. And second, the airline willingly surrendered the opportunity to sell sex in its most obvious and widespread form: by commodifying female bodies for the sake of heterosexual men. Rickenbacker’s public statements basically presumed that his steward corps would thereby stand out as asexual when compared to his domestic competitors like United, Delta, and American, who used stewardesses on their flights.

The reality of Eastern’s stewards was, however, quite a bit different. Indeed, these men embodied even more of the “gay” traits seen in Pan Am’s previous “Rodney” campaign, and the airline promoted them as men who remained intriguingly desirable, especially to female customers, whom the airline hoped to attract. Eastern’s most adventurous attempts to eroticize stewards involved their vibrant uniform design, which stood in marked contrast to the more conservative attire worn by stewardesses. Stewardess uniforms of the 1930s were very different from their later manifestations in the 1960s, when they became scanty, bright, form-fitting, fashionable outfits that highlighted the woman’s sexual appeal. Instead, the uniforms of United’s first stewardesses and all other female uniforms from the decade obscured their form. United commissioned a traditional long skirt coupled with a blazer and a knee-length cape for cold weather. The material was cut generously to conceal the woman’s body under layers of drab gray fabric.

Meanwhile, the steward uniforms at Eastern had the opposite effect, accentuating the man’s broad shoulders and tight waist (figure 3). Stewards looked thin and muscular, as the jacket’s wide shoulders tapered off to a more compact lower torso. The pants, starting tight on the waist, then continued this sleek, ever-slimming line all the way down to the ankles. Even the overlap of the coat and the pants was skin-tight. The overall effect was not just to accentuate the steward’s form but also to ensconce him in the most modern and sophisticated style of the day: streamlined design, which celebrated aerodynamic features.44 It was surely more than a coincidence that these uniforms accomplished the same sort of tight body-sculpting on the steward as the DC-3’s sleek chrome exterior and integrated wings accomplished on the aircraft’s form. Eastern’s stewards, far more than stewardesses of the day, were at the pinnacle of modern style.

The steward’s streamlined uniform, with its inspiration from other service uniforms found in upper-class urban society (bellhops, doormen, elevator attendants, and ship stewards), very much belonged to the elite “gay” world. And like its counterparts in these other service professions, the Eastern uniform drew attention for its use of color just as much as its cutting-edge form. After all, it was a dazzling color burst in the otherwise stark airplane cabin. The steward’s white coat already stood out, but the designers took it one step further, accenting the lapel and sleeves with red zigzag piping. The resulting ensemble contrasted sharply with most other forms of professional dress. However, as designer Gilbert Rohde suggested in 1939, this use of color was in the avant-garde of men’s fashion: “No longer does [the man of the future] submerge his personality and stifle his imagination in the monotony of the twentieth-century business suit. He, too, is gay, colourful, and different.... In the nineteenth century, something happened in our Western World, and he gave up his gay dress without a struggle. In the twenty-first century, the strange custom of dressing like a monk will have disappeared.”45

FIGURE 3. “Fashion Preview” for Eastern steward uniform. Great Silver Fleet News, November 1936, 8. Courtesy Eastern Air Lines.

Eastern bought into this futuristic idea that “gayness” needed a space in men’s fashion. Interestingly, however, it limited its uniform makeover to stewards, not the more traditionally manly pilot corps. Pilots, after all, derived their manliness from technical prowess and, quite often, a military or barnstorming background, not a career devoted to service and style. The pilots were shrouded in drab navy blue military-style suits, not streamlined to show off their bodies.

In their public relations materials, Eastern marketed their stewards with the same techniques that one might expect of female stars in the pages of Vogue. The airline’s public relations magazine the Great Silver Fleet News introduced the new uniforms in November 1936 under the headline “Fashion Preview.”46 Below the photo of the steward modeling his uniform came a detailed piece-by-piece description of the outfit. The description itself was more terse than one might expect of an analysis of women’s clothes: the jacket, for example, was efficiently described as “a custom-built white jacket with smart red piping and lettering.” Yet the overall effect was for readers to view the steward as a fashion model whose clothes and looks they could scrutinize and enjoy.

Follow-up stories had a similar emphasis; a month after the uniform’s unveiling, an Eastern steward “led the style parade in his jaunty uniform at the 10th Anniversary Fashion Show.”47 It seems strikingly unusual that a man would “lead a style parade” at a major fashion show, especially as these were heavily female-dominated events, usually occurring in department store parlors and restaurants where middle-class women spent their days.48 A decade later, thousands of men would lead parades, but these would be in honor of their military valor in the war, not their looks and clothing.

Another glamorous sighting in the steward’s first year included a night of publicity at the elite Rainbow Room nightclub atop New York’s Radio City, where a steward awarded a lucky attendee a free flight to Washington, D.C. The Rainbow Room, with its commanding views of the city and bold use of color and streamline motifs, typified the cosmopolitanism and over-the-top style of the 1930s upper-class “gay” nightlife. The club itself was not particularly known for being sexually libertine, attracting instead an upper-crust crowd looking for a night of fun in opulent surroundings with good music and ample alcohol. That said, historian George Chauncey identifies it as one of several new upper-class clubs opening at the time that “were heavily—but covertly—patronized by gay men and lesbians.”49

FIGURE 4. A suggestively playful photo and blurb employing homosexual innuendo in Eastern’s company magazine. Great Silver Fleet News, June 1937, 3. Courtesy Eastern Air Lines.

Eastern’s description of the steward’s visit to the Rainbow Room played quite flirtatiously with how its attractive and fashionable stewards were perceived in this “gay” nightlife environment, even potentially suggesting male-male eroticism (figure 4). The company’s magazine laid out the story with a photo at the top of the page depicting a dapper steward in his stylish uniform presenting the free trip to a female attendee. Just below the photo is the headline “EAL [i.e., Eastern Air Lines] Invades Gotham P.M. Life.” The headline and the photo together stress that the steward, as the main public relations representative for the company, took the leading role in this nightlife “invasion.”

The article begins just below the headline with an unusual choice of words, given the steward’s prominence in the evening’s festivities: “Gay guests at the Rainbow Room, Radio City’s smart nightclub, recently were jolted pleasantly out of their top-hat, white tie complacency when EAL zoomed in.”50 Of course, those in the audience wearing top hats and ties were the men, not the women. So, what about Eastern’s presentation would have aroused them? If the passage is read in a nonsuggestive way, these male guests, having a perfunctorily good time, started to really enjoy themselves (and thus could be identified as “gay guests”) when Eastern enticed them with a free ticket to Washington. Arguably, men could be “jolted pleasantly” when presented with a chance to fly on an airplane.

Yet, among the sexually savvy in 1930s New York, another more flirtatious reading of the text would be obvious: the good-looking, fashionably dressed steward is jolting the “gay guests” among the men. Without question, the steward would have made quite an impression not only on straight women in the audience but on the gay men as well. But whether this interpretation dawned on more than a few readers, and perhaps a clever copywriter, is impossible to know. The word gay had definitely acquired its double meaning by the late 1930s, but only for those knowledgeable about the homosexual underworld. At the very least, the homoerotic juxtaposition of a male steward arousing even male patrons among the evening’s “gay guests” probably struck many readers as peculiar. At the most, though, it suggests an awareness of the polymorphous sexual desires that Eastern’s fashionable steward corps incited.

THE RISE OF HOMOPHOBIA: CASTING THE STEWARD AS ANTIHERO

As stewards increasingly straddled the lines between masculine/feminine and straight/gay with the rise of new aircraft technology, they also became lightning rods for a very real but still inchoate homophobia. This homophobia was expressed in more subtle ways than outright accusations of sexual impropriety or full-throated castigations of the stewards’ gender performance. Instead, it was often cloaked in humor and sarcasm, marking it as more muted and less violent than America’s outbursts of the 1950s, when gay bashings and other forms of vigilante justice become prominent. Surprisingly, the public relations materials from Eastern and Pan Am—the same media that promoted the steward as attractive, dapper, and doting—also partook in the steward’s hazing. Both airlines devoted pages of their in-house publications (circulated both among employees and passengers) to poking fun at stewards for their gender-nonconforming work and persona. Even stewards’ employers recognized that their softened masculinity, while advantageous for luring female passengers onto their increasingly safe and comfortable planes, was out of sync with much of the culture.

Just a few months after Eastern unveiled their stewards, the airline’s public relations department playfully poked fun at their compromised masculinity. The humorously sensationalized article “Flight Steward Reveals Drama” from the April 1937 edition of the airline’s in-flight magazine actually covers the mundane activity—when not performed by a man, that is—of changing a baby’s diaper. The “drama” of the story involved a six-week-old baby who was traveling with his father and grandfather and whined incessantly until the doting steward realized he had a wet diaper.

Playing the proper male-privileged role, the child’s father and grandfather were completely unaware of how to change a diaper. “Their knowledge of diaper technique, I soon learned, was minus nil,” noted the steward who penned the article. “Well, something had to be done.” For the steward, acting heroically in this scenario meant exposing himself as someone able to do the womanly work of changing diapers. So potentially emasculating was this onerous duty that he chose to withhold his name for the article. At the same time, he desperately—to the point of agitation—clung to his manhood by suggesting his status as a dad had given him this gender-bending ability: “The flight-steward who contributes the following picture out of his gallery of memories prefers to remain anonymous, but submits that he is a father in his own right as proof positive of his knowledge of the details described below. ‘What certificate,’ he asks a trifle aggressively, ‘what certificate can serve better than a marriage certificate as a diaper diploma?’”51 A marriage certificate certainly provided some cover for the steward. At the very least, it allowed him to present himself as a conventionally heterosexual man despite his feminine skill set. Yet the baby’s father and grandfather also presumably had marriage certificates and had managed to keep their manly reputations unscathed by the burdens of child care.

What drove this steward to the abjection of anonymity was the tension between his own masculinity and the airline’s financial success in the age of the DC-3. The airline sought to assure its ever-diversifying clientele that stewards could assist with the “motherly” tasks of changing diapers or feeding babies, even though the steward’s gender made many passengers suspect he would perform them poorly. At the same time, such work raised eyebrows among other men, who sensed that stewards’ manliness was more deficient than they had initially suspected. In lieu of their stewards’ enduring this concern unchecked, the airline opted to poke fun at the situation, surely hoping that laughter would defuse the tension between their stewards’ role and society’s more chauvinistic notions of acceptable manly behavior.

An even more striking example of homophobic humor is the short-run comic Tale Wind, found in the Pan American Air Ways magazine that was distributed to Pan Am employees and customers (figure 5). In the summer of 1938, an in-house artist named Vic Zimmerman published the first of eight comic strips that followed the travails of Barney Bullarney, a fictitious Pan Am steward. Already with his debut, the reader learns that Barney is a lightning rod for other employees’ aggression. The first comic strip portrays a pilot looking for “our glib young ambassador of good will” as he passes through the hangar where mechanics and copilots are busy playing cards. Noticing that Barney is actually approaching the hangar from the other direction, the mechanics prepare to welcome him by hurling wet sponges at his face. Meanwhile, Barney’s foremost nemesis, the mammoth mechanic Blimp McGoon, gives the reader a grand introduction just as Barney sets foot in the room: “Well, here he is, folks—That dizzy young dean of stewards, with 687,000 passenger smiles to his credit—Folks, we give you Barney Bullarney!” The following frame shows the “dizzy” (a term laden with feminine connotations) Barney with a smile on his face and a big wave, as though the repeated hellos and good-byes aboard the aircraft had been fixed in his muscular memory. Barney, who is round-faced, with pronounced dimples, and dressed impeccably in his three-piece steward uniform, is completely unaware of the sponge soaking that awaits him. Instead, he greets the men warmly, calling out, in a peculiar dialect, “My frans!”

The publication date of early July 1938 means Barney Bullarney debuted within days of a far more famous comic strip character, Superman. With his premiere at Action Comics on June 30, the Man of Steel ushered in a new genre of comic book hero, a man so strong and possessing such otherworldly skills that he came to be known as a “superhero.” In comparison to this flying superhero, Barney was far inferior. In fact, rather than heroic, he was coded in multiple ways as a classic “screwball” character, whose appeal to audiences was his zany behavior and his ability to evoke laughter.52 Barney’s screwball contemporaries were the cartoon film stars Daffy Duck, Bugs Bunny, and Elmer Fudd, who premiered at roughly the same time.53 Each of these screwballs, like Barney, shared a peculiar speech impediment that softened him to the extent that he couldn’t be taken seriously. The only “superhuman” trait of screwball characters was their masochistic ability to endure endless abuse and violence without ever showing its effects. (Daffy and Elmer in particular would be shot in the head, dropped off cliffs, or beaten to a pulp in nearly every film.) These tropes are already evident in Zimmerman’s first depiction of Barney, who comes across as dim-witted and unmanly as he walks right into a hostile crowd of men ready to unload on him.

FIGURE 5. The debut of Tale Wind. Pan American Air Ways, July-August 1938, 10. Courtesy Smithsonian Institution Libraries.

In two of the other seven installments of Tale Wind, Barney endures more demeaning physical insults than in his debut (figure 6). Both depict the burly mechanic Blimp McGoon bending Barney over his knee and spanking him or punching him in the rear, much to the delight of an onlooking crowd of Pan Am coworkers. The impetus for the punishment in each case is a so-called “bright idea” that Barney thinks up, which is met by the other members of the Pan Am staff as foolishly funny. These men then turn Barney over to Blimp for his ritual punishment. Blimp’s abuse of Barney as the snickering crowd of other Pan Am employees look on, conjures up images of a sadistic gang rape, replete with anal penetration. It also highlights the chasm between traditionally manly working-class roles (the mechanic) and the more effete man working in service professions. Yet, as though Barney embodied all the masochistic qualities of the most timid victim, he returns in each subsequent episode of Tale Wind as chipper and accepting of his co-workers as ever.

While completely fictional, Tale Wind nonetheless served as a cautionary tale for real-life stewards. Some coworkers and members of the public—especially the most macho and chauvinistic men—would inevitably greet them as dim-witted “screwballs” worthy of ridicule. And the main trait that made Barney so vulnerable was true of real-life stewards: unlike the other men at the airlines, their embodiment of manhood was not tied to their physical skills or management prowess. Instead, they were soft and dapper, relying on good looks, charm, and servile work for their livelihoods. The quasi-gang rape scenes in Tale Wind thereby stand out as alarming artifacts of a very real homophobia that flew just under the radar.

REARMING MASCULINITY

Historians of gender highlight World War II as a watershed moment. Mobilization allowed women to occupy positions in the workplace that men otherwise held. These women’s gender bending was celebrated in the war years, allowing many of them to connect with long-suppressed yearnings to hold a job on par with men. Less notable but equally true is that some men—at least in the male-only regular corps of the military—found themselves in notionally feminine jobs, working as cooks, secretaries, or nurses. Wars, after all, are moments when societies relinquish various fictions regarding proper gender roles: men become largely self-sufficient on the front, while women become equally autonomous and multi-capable at home.54

FIGURE 6. Abuse of a steward by his coworkers in Tale Wind installment. Pan American Air Ways, November-December 1938, 7. Courtesy Smithsonian Institution Libraries.

Nonetheless, predominant notions of manliness tend to harden during wars. Whatever room war creates for men to enter women’s work doesn’t prevent the masculine ideal from becoming more tied to aggression, risk taking, and exposure to death and violence. Along these lines, the steward’s softer masculinity of the 1930s was increasingly out of place as America moved toward war in 1940 and 1941. As most stewards joined the sixteen million men who registered for the draft in October 1940, Eastern rushed to envelop its stewards in military-inspired rhetoric and jettison their “gay” public image.

In June 1941, just months before Pearl Harbor, the airline’s in-flight magazine carried its most thorough justification yet of Eastern’s all-male flight attendant corps. Most notable is how the airline now disavowed notions of style. Entitled “Eastern Carries the Male!,” the article noted that Eddie Rickenbacker’s choice of stewards was based “on the premise that air transport had grown up and that service rather than glamour or silk stockings was needed to keep the clientele pleased.”55 The article then stressed that the steward corps possessed a military-like discipline and sense of purpose. It recounted the World War I heroics of Walter Avery, Eastern’s head of stewards, who had famously downed one of Germany’s Red Barons while serving on the Western front. By emphasizing that the flight attendants were led by two World War I flying aces, Captain Eddie Rickenbacker and Walter Avery, the article cast stewards as the loyal foot soldiers of distinguished military men.

Despite their misgivings, the war ultimately forced even Rickenbacker and Pan Am’s CEO Juan Trippe to abandon their all-male flight attendant corps. Eastern began to address its male labor shortage in 1943 with its first female hires since the company’s earliest years of passenger service. Pan Am followed in 1944 when it hired seven women in March, then an additional twelve a few months later. Just as much as United’s first stewardesses from 1930, these new hires were trailblazers. They fulfilled all the duties of their male counterparts, including loading mailbags into the plane’s cargo hold, rowing passengers to the docks, and handling customs forms. A member of Pan Am’s first stewardess class, Genevieve Baker, recalls her instructor saying, “You will be paid on the same basis as men stewards. You will have the same chances of promotion but—don’t use your sex as an excuse. Never say, ‘You can’t expect a woman to do that!’”56

Only in one key way did Pan Am distinguish between its male and female flight attendants. Given the fear that women would not be able to work the sustained hours demanded on long-haul routes, the company’s stewardesses were concentrated on shorter trips from Miami to Havana and Nassau, while men were still exclusively used on the routes to the Canal Zone, Brazil, and Buenos Aires. Over time, these gender-based restrictions would give way as stewardesses proved their abilities even to the originally dubious Rickenbacker and Trippe. Their success, when coupled with the more intense homophobia and continuing technological advances of the postwar era, further led the 1930s steward toward historical obsolescence.

THE 1930S STEWARD: A POSTMORTEM

As workers who were also public relations tools for one of America’s most technologically advanced industries, stewards and stewardesses in the 1930s embodied an idealized future that was supposedly being wrought by the high-tech machine age. In this sense, they were vessels for the aspirations of what all of U.S. society would strive to look like once the pain of the Depression gave way to new prosperity, thanks to new technologies like the airplane. No wonder, then, that both stewards and stewardesses captured the imaginations of ordinary Americans. Hollywood fell in love with these women who could gallivant from New York to Los Angeles, exhibiting poise, professionalism, and alluring beauty along the way. Meanwhile, in the mode of the dapper “Rodney the Smiling Steward” and his confreres at Eastern Air Lines, stewards found financial stability and access to a high-society lifestyle despite being low-skilled workers in the heart of the Depression. These men enjoyed the same exhilarating mobility that stewardesses did—both a geographic and socioeconomic reach beyond what their education, skill set, and financial resources would otherwise permit.

The steward’s appeal was very much grounded in a social milieu peculiar to the 1920s and 1930s urban elite. Airlines’ clientele at the time were exclusively America’s very rich, and the companies hiring men actively sought to ensconce the steward in the “gay” leisure world these passengers already knew. Thus stewards were servile but also sophisticated and fashionable. Their natural good looks could be used to sell air travel. Their cutting-edge, dapper uniforms granted them access to upper-crust venues like fashion shows and nightclubs where they could promote air travel as glamorous, just as opulent and exotic as a night out on the town. Of course, in some ways, the steward was no more than a bit player in the “gay” social scene of these upper-crust elites. It wasn’t his privilege to overindulge in the life of good food, fine alcohol, dancing, sexual excess, and opulent locales. Yet just as the elite men who partook in this charmed life were more feminized by their surroundings, so too was the steward vis-à-vis other working-class men. His livelihood depended primarily on his looks and style, and he was even less credentialed than the nurses who worked as stewardesses.

The composition of the 1930s flight attendant corps depended on complex interactions of cultural notions of gender and sexuality, technological advances, racial segregation, and economic considerations that at times favored stewards and at other times compromised their viability in the job. On the whole, stewards garnered a fairly generous amount of tolerance, even as they were dandied up and promoted as inviting sex objects by their respective employers. This tolerance suggests an easiness with white masculinity norms in the prewar era that would virtually vanish with the onset of hostilities and would be ghettoized after the war, prospering almost exclusively in the gay male subculture.

At the same time, however, the sadomasochistic cartoons chronicling the abuse of the fictional steward Barney Bullarney point to an aggressive homophobia brewing in 1930s society. These images, while just cartoons, expose a visceral desire among some to maintain a more macho code of manhood. This trend would only intensify after World War II and would lead the flight attendant corps to become increasingly a female-only domain. Indeed, as planes became even more comfortable after the war and the culture grew more aggressively homophobic, the ratio of stewards in the flight attendant corps began its precipitous decline from one-third to well below one-tenth.

Not surprisingly, by the mid-1950s both historians and journalists had begun to misremember flight attendants’ history. Amaury Sanchez and his peers from the 1920s were virtually forgotten, and United’s stewardesses hired in 1930 were now hailed as America’s very first flight attendants. Also overlooked were the Pan Am and Eastern stewards hired before the war, some of whom continued to live—and even work—for several more decades. Equally neglected was these men’s deeper historical significance for gender and sexuality history: that a gender-bending, potentially homosexual cadre of “gay” stewards had thrived for an entire decade.