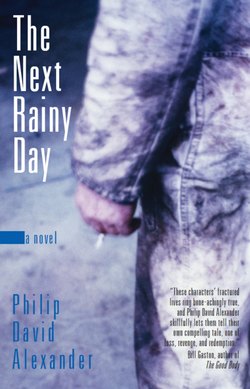

Читать книгу The Next Rainy Day - Philip David Alexander - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Bert Commerford

ОглавлениеThere's no halo around my head. I want to be damn clear about that. And I'll tell it straight because that's the only way I know. A lot of people would throw some kind of slant on it, some psychobabble that lets them put the blame on someone or something else. But I don't go for that. And I'll tell my version because that's the only one I truly know. There won't be any of this business where I try to get inside someone else's head. I hate that shit.

There's no way around it: things happened that put my family on a bus ride to hell, and there were times when it seemed like it had no brakes. And we crashed slowly. We didn't just slam into an overpass and twist and shred; we had three bad collisions, with plenty of time in between each one. I can't say that I was the only one in the driver's seat, but I took my turn, pedal to the metal as they say.

These days I watch a lot of those TV talk shows that start around 10:00 a.m. and run back to back until damn near dinnertime. I see all these losers willing to air their dirty laundry in front of an audience — usually of an audience of slobs who should be at work, but we won't go there. The so-called guests sit up on stage, waiting for the mike to hover in front of them so they can cry and blame their fuck-ups on Mom, Dad, a perverted uncle, or the government, or just society in general. What they don't realize is they're just garden-variety morons with daytime TV problems and no one really cares about the husband cross-dressing or that the wife has declared herself a lesbian after thirty years of marriage. I watch them because their lives are coming unglued and there's something oddly gratifying about how seriously they take their pathetic, self-made woes, tabloid bullshit. I've drafted up a couple letters to some TV talk shows in Toronto and New York.

I basically ask, “You want a story about a family mess? A real tragedy? Sit back and read this.” Those letters sit stamped and ready to go. We'll see what happens. Some days it seems like a great idea. Other days I figure, why lower myself.

It's tough to know the best place to start and what to tell and what to leave out. I mean, there are some things that I'm accused of having done that I'm still not so sure about. I've got no way of confirming it. So I'll tell my side of things using my head and my heart, but mainly my gut.

A few years ago I had a pretty decent lot in life. Things weren't perfect, but we got by and everyone was in one piece. I had an auto garage that I took over from my father. He'd had the business for years, built it from the ground up. I had a good, solid wife and two sons, both full of piss and vinegar. Travis, my youngest, channelled his energy into hockey. The other, Rusty, old enough to know better, channelled it into whatever was closest: cheap whisky, women (mostly underage), bar brawls. Sure, I had worries. Who in hell doesn't? But one morning not too long ago, I woke and felt change in the air, and in my gut.

I'm not one for remembering dates. I used to get in hot water all the time for forgetting birthdays and anniversaries. But I remember October 8, 1993, very clearly. That's the day when things started to slide. I got up that morning before dawn because Travis had a pre-season game over in St. Catharines. I left the house just after six and crossed the road to my garage, Commerford & Sons Auto Service. It was cold as hell; I remember turning on the little electric heater in the office. I was out of cigarettes, so I'd planned to just dart across the road, grab a pack, and get back over to the house to wake the boys and whip up breakfast. I helped myself to a pack of Export As and some gum from the little confection stand we kept in the office. I left a note for Vic, my mechanic and right-hand man, reminding him that Emily Stewart was bringing in her Toyota for a tune-up sometime before lunch. And then I locked up. The funny thing is, I also remember turning toward the house after locking the office door. I stood there and admired the place, nodded and approved of the tall, rock-solid Victorian home where my wife and boys were still in their beds. I gloated a little, I guess. The guys in town at the Copper Kettle Diner would tease me when I dropped by for coffee. They'd get a kick out of telling me that most guys had to commute to work, but me, I crossed a two-lane road to get to work but commuted to get a cup of coffee. They're as good a bunch of guys as you'll meet. When things really came off the rails, they were there for me, like a family.

Let's get back to that cold gray morning, though. I finished gawking at my home and made a quick check left and right for traffic. There was never much on our road at that time of day, especially on weekends. Over on my left, near the flashing red light above the stop sign at Dunn Road, there were two township trucks. I could just barely make out the little Battleford Township coat of arms on the driver's-side door of the smaller one. Three workers were moving about, one of them with what turned out to be surveying equipment under his arm. I checked my watch and wandered down to see them. Chuck Wood was the assistant works department foreman. He was standing with a set of plans and municipal zoning maps under the arm of his canvas jacket. Back when Chuck used to drive a cab down in Niagara, I serviced it for him. When he got the job with the township he was key in getting me the contract to service their fleet. He wrote a letter to the mayor and bragged about my great service and the quality of my work. And I had that contract until Charlie Dent lost the mayor's seat to that asshole Gavin Bascomb. Anyway, I reached Chuck and greeted him with the usual, “How much wood would a woodchuck chuck if a woodchuck could Chuck Wood.” He didn't smile. Just wasn't himself. I asked him if he was milking the township for some overtime, doing some work that could have been done on a weekday. That didn't get a smile either. Traffic lights? More of my tax money being spent, I asked him. He just shook his head and told me to stop joking around, he was freezing his ass off and didn't want to be out on the weekend. He complained that the contractor for the township kept on wanting stuff double- and triple-checked. I asked him what contractor and he just laughed. And then I think he clued in that I wasn't pulling his chain.

“You mean you honestly don't know?”

“No, Chuck, so why don't you tell me because I'm getting nervous here.”

Chuck looked confused. He waved over one of the other men, an acne-faced guy in overalls.

“Lenny, notices went out, right?”

The guy looked at me and looked back to Chuck and said, “Yeah, of course. At least three went out.”

“And there's been no objections?”

That's how I found out that plans had been issued and approved and that Commerford Road, a road where my family had lived and done business for two generations, was going to be cut off. “Truncated” was the word Chuck used. Here's the thing: Crandy Manufacturing was halfway through building a new plant about three miles north of me. And the township had decided to bypass Commerford Road. They were going to take Dunn Road and build it into an overpass. The planners figured it would better serve the tractor-trailers hauling to and from the new factory. Besides, there was nothing much on Commerford Road except for my home and business, a couple of houses, and an abandoned soybean farm.

There was an old widow named May Bennett down our road about a quarter-mile. She was our closest neighbour. My boy Rusty used to cut her grass in the summer. She'd flip him five bucks for his trouble. Once Rusty got older and more interested in stealing and busting skulls around town young Travis took over. My wife, Wanda, would bring her baked goods once a week and would even clean up her kitchen now and again. We helped May out as best we could. May was losing her marbles, though. She chased her cats with a broom, called my sons by different names all the time, and wore a tattered old housecoat all day, every day. I knew she was awake because I could hear her nail-on-chalkboard voice yelling at one of her cats. I wandered down there and said hello, and she took a moment to figure out who I was. Her eyes seemed glazed, and I caught a whiff of her sour odour from two feet away. She complained that her kids were out of control and costing her money. She grumbled about having too many children.

“What children are we talking about here, May?” I asked.

“Those ones,” she screeched, pointing at two scruffy-looking cats crouched like oversized hamsters near her mailbox.

I changed the subject, asked her if she knew about the plans to rebuild Dunn Road and bypass our place. She went inside and came back out with a notice from the township. She handed it to me and said that her eyes were getting bad so she hadn't read it. She told me her son had warned her about the changes. I felt a knot form in my gut as I looked at the notice. There it was in black and white.

I stormed back to the house. I'll admit that I was fuming. I kept my eyes on our front hallway light, which was on. I tripped and stumbled into the ditch, I was walking so fast. That just got me wound up even more. I damn near ripped the door off its hinges rushing inside. Travis hadn't seen the notice before. I could always tell if Travis was lying to me, and he was clean this time. I asked where his brother was and he pointed upstairs. I took the stairs two at a time and pushed my way into Rusty's bedroom. He was on his back, lying on the floor wearing ripped boxer shorts that showed part of his business just hanging there. He was smoking a cigarette and listening to the headphones. I plucked them off his head and they got tangled up in his hair.

“Hey, old man, that fucking hurt,” he told me.

I told him to watch his mouth, buy some new shorts, and go to the barber. And then I held the notice right in front of his eyes.

“Recognize this, boy?”

He took it and studied it. A smug little grin appeared across his face.

“No, first I've seen of it.”

“If I find out you're shitting me, Russ …”

He gave it back and swore up and down he'd never seen it, hadn't collected the mail in ages. That added up. He'd become a lazy bastard the last few months. The effort of walking to the mailbox would've been too much for him.

Wanda was standing in the hallway, near the top of the staircase. I closed Rusty's door and waited for her to speak. She was still a very pretty woman: her long brown hair had taken on just a strand or two of gray, and her solid farm girl face had taken on a fair bit of weight, but remained fresh and wholesome despite her weak heart. She didn't speak. She looked at the floor instead, gripped the top of the handrail until her knuckles went white. I knew by the look on her face.

“For God's sake, Wanda, why? Why would you keep this from me?”

She told me she was worried that it would kill me. She dreaded a long and ugly fight with the township. She stood there, close to tears, arguing her points: business at the service station was slow, Travis was playing more and more games, and maybe we needed to move closer to a larger town or city. She sniffled and said that she felt isolated, had hinted as much recently, but I had ignored her or just didn't clue in. There was a letter from the township on the way outlining a compensation package, and once she'd gotten the details she had planned to sit me down and show me the offer. She was confident it would be a generous one. She reached into the pocket of her jeans and pulled out two notices from the township. I hit the roof. I mean I really unloaded. I called the whole thing deceitful and pounded my fist on the wall. There I was busting my ass and trying to make the business work and my family was running interference, rolling the dice with our future. Russ came out of his room and stood between Wanda and me. Russ had taken to doing this sort of thing, poking his nose in where it didn't belong. He knew damn well I'd never hit his mother, but he'd always shove his nose in and act like he was protecting her. In return, Wanda would go to bat for him regardless of how much he fucked up. They'd become a team. I realized it as I stood there shaking my foolish head that day.

“They're rerouting the road that brings in the traffic, our business!” I said.

Rusty said, “What business?”

I stepped toward him and flashed him a warning with my eyes and teeth. Wanda wedged herself between us.

“It was my idea, Bert. Please, let's sit and talk like adults.”

When the smoke had cleared Wanda and me sat and drank coffee at the kitchen table. I'd originally searched the back of the kitchen cupboard and found some whisky. I kept it there as a “just in case.”Wanda said there was no such thing as just in case, once you quit that was it. And she said she hid those notices for that very reason. She figured I'd hit the bottle for a few days upon getting the news, and then I'd dry up and become obsessed, run myself into the grave over getting vengeance on Bascomb and his idiots at Town Hall. I put the bottle back in the cupboard and we brewed coffee. She cried her eyes out, told me she felt really stuck, that it turned her stomach to keep a secret from me, especially one that would leave me looking like a fool. She pleaded for me to roll over, put my hands up in surrender because there would be a good chunk of change from the township. There was no way in hell I was leaving my home and business. She'd always talked about moving to the city, and I guess she saw this as her chance. Things had been slow, and I think Wanda thought that I'd see the compensation offer and say what the hell. She saw the whole mess as a chance to have the decision made for us.

There wasn't much relaxing, and certainly little sleeping for the rest of the weekend. Wanda moped around, stopping her routine now and again to say how sorry she was, but she had meant well. Travis hitched a ride to his hockey game. Rusty took off somewhere. There was no use asking Rusty where he was going or what time he'd get home. Travis was fifteen, level-headed and easygoing. He had no problems with curfews and pay phones and notes left on the kitchen table telling us where he was. Rusty, on the other hand, was nineteen, bullheaded, and played his hand close to his vest. He kept the schedule of a damn barn owl: up all night and home to his nest at dawn. I spent most of that weekend alternating between being angry with Wanda and realizing that she had a point. The township had changed. Business was slowing to a crawl. And she was right; I would have become a man possessed if I'd seen those notices. Jesus, I was already planning my strategy with Mayor Bascomb on Monday morning. Here's the thing: deciding to move on based on money and the needs of my family was one thing. Allowing the mayor and some factory to muscle into my backyard and tell me when it was time to move, well, that was another thing. And I already felt like an idiot. I'd seen the township trucks buzzing around the area and thought nothing of it. Gus and the boys at the diner had said things like “Well, things are really changing” and “We feel bad for you, Bert.”

Hell, I thought they were just sorry about how tough it was getting to make ends meet.

So I sat and I waited for Monday. And I fumed. And I decided to fight the rezoning and “truncating” as hard as I possibly could. There's nothing like being hoodwinked to piss a guy off.

Looking back on it I should've known it would be a short fight. I got to the township offices at 8:30 on Monday morning. I sat in the foyer and watched a frumpy woman I'd never seen before open up the switchboard in between sips of coffee. At exactly 8:45 she looked at me and said, “Can I help you, sir?”

I asked if I could see Mayor Bascomb. She studied me like I was insane, as if I'd asked to speak to the Prime Minister. It used to be I could wander into the old town hall and go straight to Chuck Dent's office, sit with him and shoot the shit for ten minutes. The new offices were larger, no doubt built with the idea that the township would become a town, and maybe even city one day. The receptionist had a little headset on. She'd taken the mouthpiece and pushed it closer to her lips. I couldn't hear what she was saying, but she eventually looked at me and said, “Can I tell the mayor your name?”

“Bert Commerford.”

The mayor's assistant came to fetch me and led me to his office. I didn't know her, either. She walked like she was late for a train, and I followed her down a long tunnel of wallpapered hallway. There was lots of art on the walls, ugly stuff that looked like someone had drunk paint and then puked it all over a canvas. The old town hall had some nice Group of Seven prints on the walls. I wondered what happened to those paintings as we neared the mayor's office.

Gavin Bascomb's father had been an accountant who moved in from Toronto and set up shop in town. He was a typical city man. He liked to talk and had an opinion on everything. When your turn came to talk he would glaze over and pretty much ignore you until you stopped and he could shoot his mouth off some more. Gavin was more polite and — I had thought — more patient than his old man. He'd moved out of Toronto when he was a boy, helping to shed the city habits and arrogance. Gavin was a grade-A student in both elementary and high school. He came back to town after he graduated university. He worked for the local paper for a while, took over his father's business when the old windbag died. He ran for mayor at the tender age of thirty-two. He was quick on his feet and had promised to revitalize the area if he was granted a chance in the mayor's seat. Once he took office he immediately began inviting businesses to set up in town, enticing builders to plan subdivisions, fast-tracking their permits. He'd already made some enemies, especially among the old-timers.

He invited me to sit down. A quick but firm handshake, no offer of a coffee or glass of water. He wanted to keep it business, so I did the same. I told him I'd never received the notices. He dug his chin into his neck and frowned, as if this were impossible. It wasn't long before we were arguing. His angle was to lecture about the small changes and adjustments I had to make for the long-term economic good of the community. He spoke to me like I was a dumb-ass. He assumed that because I fixed cars and pumped gas for a living I was simple, maybe plain stupid. He stood and asked me to leave when I pointed out that they were all in bed together: him, Crandy Manufacturing, the builders, and the newcomers to town. He said the municipality had done its due diligence in sending out the notices, and if I hadn't received them it was too bad; construction was set to begin within two weeks. We continued to squabble about it, but I could see his father in him. I saw that he wasn't even listening. He played with the cord to his telephone while I spoke. Checked his watch often. And probably peered across his big mahogany desk and saw a used-up old fool. Old Bert, sitting in his office demanding a say when it was too late. There's a new factory in town, new modern road, new subdivision for all the workers, convenience stores, hamburger joints. And then there's Bert and his aging service station with the old-fashioned service bays and two lousy gas pumps, and neither of them pump diesel.

I went to see Marc Savard the following day. Savard ran the little newspaper in town. He was scared of me, I could tell. He squirmed in his chair as I talked. I handed him something for his Letters to the Editor section. He read the first few lines and his fingers began to tremble. He waved the letter around as he spoke, his voice all shaky.

“Bert, I can't print this. It's not that I don't empathize, really. Look, I can't publish a scathing letter that rips apart the very people who are trying to create jobs —”

“You mean the factory folks who are promising you all kinds of advertising, huh, Savard?”

He pinched the bridge of his nose and sighed like woman. He insisted that that was not the case and that he understood my position. He said that if he printed my letter, Bascomb and his people would just take out space and reply that they'd followed the Planning and Municipal Acts. Everyone had been notified. There had even been a hearing that hardly anyone showed up for.

“Why don't you go and speak to the head guy up at Crandy? He's looking to fill jobs,” said Savard.

I got up and left, flung his door shut. It was light as balsam wood. A lightweight door for a lightweight journalist.

“Hey, don't be mad at me, Bert,” he called.

Wanda and Rusty were in it together. He loved the idea of living someplace where he could be footloose and fancy-free. The bigger the town the more trouble he'd find. And she wanted out. Her dad had been a farmer, and when we were dating she'd often become quiet, suddenly depressed. I'd ask her what was wrong, and she'd giggle nervously and say, “Oh, I always saw myself meeting a man from outside of here. If we get serious, I'll never leave. I suppose you'll be taking over your father's business.”

I never really confronted Wanda any further. There was no big shit storm of a fight over the whole thing. And I'm glad that I left her alone in the days that followed. Here's the thing: the worry and stress of taking those letters sealed her fate in the end. Her already feeble heart caved under it all. She had the boys and me and all the headaches that came with us. Travis was a promising hockey player and ate up a lot of her time; Rusty was wild, and she spent untold effort covering for him and his bullshit. She struggled to balance the books; I'll be the first to admit that. We kept making a little bit less each year, and she did wonders at making that money go far. She'd spent years as the peacemaker between Russ and me. And on top of all that, she took those notices, knowing that the shit would eventually hit the fan. She kept too much inside of her and tried to stop it all from exploding.

It messes with my head to remember the night she passed away. There's not much to remember, no big deathbed scene, but there are tiny images burned into my mind. Little things that should have tipped me off and had me on the phone to the doctor, maybe. The way she shuffled around the kitchen that evening, like she was completely exhausted. The way she was out of breath when she talked. The lack of colour in her face, and the line of misty sweat on her upper lip and forehead as she washed up after supper. Hockey Night in Canada was on the TV, but she turned in before the end of the first period, said she was feeling under the weather. Travis knew something was up. He went to check on her around a quarter to ten. He screamed so loud that Rusty dropped the bottle of beer he was fetching from the fridge. And that scream from the top of the stairs sent pure fear up through my spine and into my head. I felt crippled.

Two months after her funeral, Ronald Pinkman, the town-ship's lawyer, called me to his office. He was very cordial, said the right things, asked me how I was coping and smiled small and sympathetic when I said I was still in shock, it hadn't really sunk in. He told me he was sorry to have to do this so soon after Wanda's passing. He took a file folder from his desk and opened it. He said that the township was willing to offer me a further 20 percent for my property. They had reached this decision after the mayor had called a meeting and said that I deserved higher compensation because I both lived and did business on Commerford Road. Mr. Pinkman let me take a copy of the papers and told me to think about it, but to realize that the extra money was only on the table if I signed within the week.

I went down to the Copper Kettle later that day. Gus and Baxter were there, sitting in the usual booth at the very end of the joint near the coffee and cutlery station. Gus would lean over, grab the pot, and help himself. No one cared. Gus had been going to the Kettle all his life. I joined them and we whispered about the township's offer. I said that maybe if I hired a city lawyer I could hold things up, keep my business in the process. Gus kept on telling me that nobody could take on the government, not even a half-witted municipal government. Baxter was the postman. He was a pretty straight shooter and was a fixture in our town. He knew and cared about people, and gave good advice. He tipped back the last of his coffee and got up to leave. He put his hand on my shoulder and said that he knew what I was dealing with, reminded me that his wife had passed about three years ago. And then he said that I shouldn't confuse my grief over Wanda with my anger at the Township of Battleford. He smiled and warned me not to be a stubborn old ox, and to think about my boys.

What was I gonna do? I went to Pinkman's office on the way home. I signed the deal and took their stinking money. I thought that if I settled and got on with things maybe my troubles would end.

Time became mush after Wanda died. I don't know how else to put it. I remember little snatches of our lives after the funeral, and after I'd settled with the township. But there's no flow to it all. And the other thing I remember was how I couldn't bring myself to cry for her. It had nothing to do with being scared to show my feelings. It was like I missed parts of her, but felt relieved in some respects. I knew deep down she wasn't happy, and she knew that I'd be unhappy if we picked up stakes and moved. We had this quiet little standoff, this unspoken difference between us. And it had ended in her death. I'll always be sorry that we never talked about it. It seems wrong that she had to resort to tricking me in order for me to finally understand how badly she wanted out. And that weighed heavy on my mind, so heavy that I never really allowed myself to miss her, to think about her the way a man should think about his dead wife.

I worked a lot at the station during those days. Once the construction started over on Dunn Road, I really just tied up loose ends, cleaned the place, and made it ready to go dormant, the way you wrap your prize evergreens in burlap for the winter. Vic shuffled into the station one morning and gave me a resignation letter. He looked at his shoes a lot that morning, and we both knew why. He turned up as the assistant manager of the quick-lube place up near the new factory when it opened a few months later. That's neither here nor there, and I don't blame him really. It's just something I remember.

One afternoon, in a cloud of dust, grit, and noise that comes with construction, I heard an engine roar, tires squeal, and the sound of rattling metal. I looked up from the desk in the office to see Rusty's pickup speeding onto our driveway, out of control, tires spinning. He ground to a stop, staggered out of the truck, and did a drunken wander up to the front door of the house. He messed around with the keys for the longest time, finally let himself in. Dust and construction haze wasn't the only thing in the air. I realized that I'd lost track of my boys. Rusty had been working for me, when he felt like it, but he had gone AWOL in the months leading up to his mother's death. And Travis, I had no idea how he was spending his days. I assumed he was in school, but as I watched my oldest boy stagger inside our home to sleep off a mid-afternoon bender, I sat up and assumed it was a wake-up call. I decided that maybe time should have some flow, should have some pattern. Shit, I don't even know if I'm making any sense. Here's the thing: even though I felt tired and crushed inside, I figured I needed to pick myself up and brush myself off.

It's hard to talk about Russ and Travis in the same breath. Telling their stories together is going to be tough. They're both so different, oil and vinegar in most ways. They approached things differently, dealt with obstacles and just handled their lives differently. It's not that they didn't have time for each other. They could lead you to believe they were the best of friends, thick as thieves and all that. And when Wanda died my boys' opposite natures really became clear. Travis grieved and then decided he was going to get on with life as best he could. Rusty grieved and then decided he'd raise more hell, do what he wanted when he wanted, and dare anyone to tell him otherwise.

By the time I started taking notice again, it was late September, coming up on a year after Wanda passed. I was sitting at the kitchen table having a whisky, working out how we could live on the money from the township. It wasn't a whole lot of money, but I had it figured out so we'd be comfortable when I added in Wanda's little life insurance policy, and if I sold off some equipment from my business. I also planned on keeping some tools so I could service cars for some of my regulars. When I pieced it all together like that, the financial picture wasn't all that bleak.

Travis came in and went to the fridge. I put the bottle under the table, kind of sheltered it with my foot. He got himself a bottle of beer, popped the cap, snatched an apple from the fruit bowl on the counter, tore into it, and sat down across from me.

“Hey, Dad.”

“Since when do you drink beer? You're only sixteen.”

He swigged the beer and bit the apple again.

“An athlete will have a beer now and then, after a really tough workout,” he said.

“Uh-huh. Well, Rusty shouldn't even have it in the house. I'm supposed to be on the wagon.”

“I was just downstairs pumping iron for over an hour. I'm bench-pressing my body weight three sets, six reps. I'm curling a hundred pounds for three sets, five reps. It's not like one beer is gonna get me drunk.”

I put my pen down and looked at him.

“Finish that one, put the bottle with the empties over there, and finish your homework.”

He sat very still, as if there were words stuck in his throat. He studied the papers I had spread out on the table.

“I guess we're late with your cheque for the league. I should cut it for you right now,” I said.

Travis grinned and looked relieved.

“Cool, Dad. I didn't want to ask. I know it's, you know . . .”

He pointed at the papers and shrugged. I could see that he was aware, in his own way, about money, what it takes to feed and outfit two boys, pay for hockey, keep up with the bills. Not to mention college, if that's the route they decided to go. I wrote the cheque and told him not lose it. He folded it, placed it in his shirt pocket, and swigged at the beer. He got up and left. I watched him carefully. He was getting thick in the shoulders and up through his back. He wasn't a huge lad, but he was solid.

“What do you weigh now, anyway?” I asked.

He turned and scratched his head.

“Around one-sixty, give or take. Thanks for this,” he said, tapping his shirt pocket.

He went up the stairs smooth as a cat. I could've cried right then. Despite all that had happened he was a good kid.

I'm pretty sure it was that same week that Rusty and me drove down to Niagara to see Travis play. Travis had gotten into the habit of riding down to the rink with Gerry Ferguson and his boy Emmett. Emmett was the goaltender, and he liked to get to the rink at least an hour before the rest of the team. Travis was dedicated, and when he got wind of Emmett and his father heading down to the arena so early, he was in there like a dirty shirt.

Rusty and me were on the road, radio playing down low as we sailed along the highway. Neither of us had said a word. Opening up any conversation with Russ was like pulling teeth. His silence was never just silence, simply there to let the mind wander elsewhere. It was miserable, like he wanted to piss you off with it.

He'd always been a difficult lad. I remember his teacher in grade three calling Wanda and me to the school one afternoon. We sat in a corner of the classroom while the children lined up outside for the school bus. I could see Rusty out the window; he knew we were inside with the teacher, but he never once looked our way, never showed any curiosity at all. The teacher was a plump, red-faced lady who kept fanning herself with a notebook. She told us that Russ did things randomly. Throwing chalk, ripping up library books, even slapping another student in the face without any provocation. Usually, she said, you could see these little incidents coming with most kids. With Russ, he'd be happy one minute, kicking a kid in the shins for absolutely nothing the next.

I clamped down on him at home after that meeting. I watched him and corrected him when he did anything “randomly disobedient.” I thought I'd gotten the upper hand for a while. And then one time we were in Toronto for the day, in this massive shopping mall with a parking lot so huge you needed a map. Wanda had taken Travis to fit him for shoes. Russ spotted this aquarium place and wanted to look at the fish. So I took him inside, and I was looking at some goldfish bowls, figured, hell, get the lad a fish or two. I wasn't in there two minutes and I heard someone yelling, “Hey, get out of there, now!”

I wheeled around to see Rusty standing on this little plastic step, his arm plunged elbow deep in a huge fish tank. I got over there in a hurry and pulled him off the step. He slopped water all over his pants, knocked the lights and filter askew. Turned out he'd asked one of the employees what kind of fish were in that tank. The guy told him piranhas. Russ asked if those were the fish with teeth, the ones that could eat a cow in minutes. Yeah, the guy told him. After I got him away from the tank, he held out his hand, grinning wide, and said, “See, they don't bite. That guy told me they were the ones that bite!”

For his efforts he got a slap upside the head and grounded for a week. On the way home he cast his silence over the entire car. Even way back then he could generate misery by just keeping his mouth shut and his dark little eyes focused on nothing in particular.

So we were in the car, cruising along in Rusty's fog, halfway to the rink and I tried to get him talking. I asked him if he planned to join me at the station, help wind things down and tune up the two snowmobiles we had out back. He rolled his window down a notch and lit a smoke.

“Doubt it,” he said.

I felt bad that he wasn't making any money, hadn't to my knowledge found a job. I'd been giving him a few bucks here and there. We were just coming off the highway when I said, “You know, there's a little money available for college, trade school, if you're up for it.”

He grunted and inhaled a drag. He started pushing his long, oily hair back over his ears.

“Well, you going to answer me or not?”

He looked at me, embers in his murky eyes. He didn't yell, but raised his voice enough to irritate me.

“Oh yeah, a trade, like maybe a Class A Mechanic's papers, so I can wind up with a bankrupt gas station in the middle of Shit Town, Ontario. I figure I'll just follow my thumb for a while. And I'll make my own money, thanks.”

Here's the thing: I'm a pretty easy guy to get along with, but like I said at the start, I shoot straight, and I don't take anyone's shit. I knew that Rusty had taken his mother's death pretty hard. His attitude, when he was around, was pretty toxic. That was his way of grieving her, I guessed. But he wasn't a boy anymore. He was twenty now, for God's sake. So I pulled off the road and told him there was no need to be such a pain in the ass. I held eye contact with him. He looked away. He flicked his cigarette out the window and said, “You know, I came along because I wanted to see Travis play, wanted to support my little brother. But I don't think I can handle much more time with you.”

He got out of the car and slammed the door so hard I thought he'd break the glass. I'd had it by then. I got out with him.

“Get back in the fucking car, Rusty!”

He'd already started marching away. He took his jean coat off and tied it around his waist by the sleeves, setting up for a long walk home. He turned and flipped me the finger. And then leaned forward, trudging urgently like he was trying not only to walk away from me, but maybe from his life as well.

At the time, I figured I had a pretty clear choice. I could run after Rusty and get into an argument with him, a shouting match where we'd say things to each other that we'd live to regret. I could chase the son who had distanced himself, chosen to carry a chip on his shoulder. And for a minute or two I nearly did just that. But if I'd gone after him, I'd have missed my youngest son's game. I would have been a no-show and disappointed Travis, the boy who was trying his best despite everything. A kid who had chosen to knuckle down and move on. I put the car into drive and continued on towards the arena, taking glances in the rearview until Rusty faded from sight.

The first thing I noticed was that they'd installed new lights in Janewood Arena. I hadn't been in there for months, and I felt a little guilty. It had been Wanda who'd taken Travis to the majority of his games. And later, after she'd gone, Travis usually hitched a ride with the Fergusons. The new lights made the ice look so white it was almost silver. The teams had already taken their pre-game skate and were just filing back onto the benches. There was a good crowd on hand. A few hundred, a lot of them with their hands curled around a hot cup of coffee. I decided not to go up into the stands. I stood near the goal judge's seat near the end of the rink and watched the ref and linesmen skate circles and shout to one another. I guess I didn't feel as if I belonged somehow. I also knew that there would be a handful of folks who knew me, the loser who had his business torn from under him. And that feeling was hot around my neck and face. So I stood in one place, away from those folks, and watched my boy skate onto the ice for the opening faceoff. I remember arguing with myself as I watched the puck drop and listened to skates cutting the fresh ice. A part of me said that I deserved to climb into those stands and find a seat. But I couldn't. My silence and shrinking away in the months after Wanda's death was all over me like a shiver. I argued with myself that there had been responsibilities to be tackled, I hadn't had time to hold anyone's hand. The money had to be sorted out, the station was up in the air and needed a plan. But as I watched players whirl around, listened to the shrill of the linesman's whistle, I was overcome by this accusation that attacked me from the pit of my gut. It was an angry voice, cutting through all the excuses and alibis in my head, telling me that I'd always done the bare minimum when it came to my boys. I'd always seen them as work, a burden, added pressure that compounded life's worries. And Rusty, well, I could count on one hand the number of civil conversations we'd had since he'd become a teenager.

It was the firm hand of Gerry Ferguson on my shoulder that snapped me out of it. I jumped when he touched me, and he stepped back and looked me up and down, appraised me, I guess.

“Sorry, Bert, didn't mean to sneak up on you,” he said.

I explained that I'd been under some pressure lately. He nodded and said he understood completely, asked how I was holding up, assured me that Travis seemed in good spirits and really on his game these days. Again, I felt like a stranger, having an acquaintance tell me how my boy was doing. The whole rink, its echoing sounds and distinct aroma of cold steel and faint ammonia were pressing in on me. I told Gerry Ferguson that I needed to step outside for some air.

“C'mon, I'll buy you a coffee,” he said.

We got coffee and a cinnamon bun at the concession stand and went back to where Gerry was sitting. We watched the game in silence for a while. Travis was on the first line, left wing, and he was flying, skating and working hard. Ferguson's boy was in goal and made a couple of nice stops as the first period wound down. The players skated off. I spotted Travis and gave him the thumbs-up. Gerry looked back over his shoulder and then tapped me on the arm.

“See the guy up there in the gray suit, sitting with another guy in a dark turtleneck?”

I craned my neck and picked them out. Gerry told me they were Junior B scouts, one from Stoney Creek and the other from Fort Erie. They'd been at the last two games and had approached Travis. I wasn't all that surprised; Travis had been playing like a force of nature, and he had intuition and decent hands.

“He hasn't mentioned it to me, not yet, anyway,” I said.

Gerry never looked my way, he settled his gaze on centre ice and said, “I've been playing, coaching, and involved in one way or another for twenty years now. Your boy has it. He knows it and they know it. Don't worry, he'll be talking to you soon. So will one or both of those scouts. Travis has come into his own, and Junior B makes sense. Shit, Junior A makes sense the way he's playing lately.”

They won their game that night. Travis had three assists and doled out two thundering bodychecks. On the way home I was busting to ask him about the scouts. We talked non-stop about the game and his near miss on a backhander in the middle of a goal mouth scramble. When we were over halfway home I couldn't hold back anymore. I told him that Gerry Ferguson had pointed out the guys from the Junior B teams. Travis smiled and took a drink from his water bottle.

“I was going to tell you. It's just that with everything that's happened and with Rusty, you know.”

I pulled onto the shoulder and flicked on my hazard lights.

“Travis, listen to me, B is the place to improve your skills, get better at the things that'll never grow if you stay in Triple A. You know as well as I do that these B clubs have agreements with A clubs. You're playing like an A player. If you want to make a go of it, I'm behind you. You let me worry about Rusty.”

He shuffled his feet around and avoided looking at me. Eventually, he let out a weak, “Yeah, I know, but . . .”

I told him there were no buts. That's when he told me that Rusty had been running around town with the Street brothers. Talk about feeling deflated.

I remember one time I was at the Copper Kettle with Gus and a couple of the other guys, wolfing back some BLTs and drinking coffee. Gus had been talking about the provincial police and how they'd added a second patrol area to Battleford Township. The official line was that the police had gone through some geographical reassessment and decided that the township now required a second constable on patrol. But Baxter, who had a way of finding things out, said that they'd added the extra cop for one reason and one reason only: the Street brothers. Marty and Johnny Street lived with their mother, who had been married to a biker until he vanished. They had a little sister named Cassie, a skinny little thing who walked naked around their yard, which was full of old tires and car scraps, until she was twelve or thirteen. The Street boys had both finished with school at sixteen. They made their living dabbling in various petty crimes. They sold weed and illegal smokes they'd gotten from the U.S. They always had hot property, stuff “off the back of a truck”to sell at the local flea markets. And they always had cash to pour into their cars, an assortment of junkers with chrome rims, cheap hand-painted racing stripes, and Thrush mufflers. They weren't big-time hoods by any stretch, but they were getting older and showed no signs of walking the straight and narrow. Rumour had it that they'd hit a bank down in Buffalo. When that news started making it around town the Street boys made some visits to some of the more loose-lipped residents of Battleford and the rumours soon hushed. The Streets were losers; the last thing I needed was for Rusty to get tangled up with trouble like them.

It was difficult to celebrate Travis's news about the Junior B scouts knowing that my eldest boy could be out roaming around with thugs, inches away from serious trouble. A breath away from fucking himself up, bringing more grief on the family.

We got home around ten that night. Travis went upstairs to tackle some homework. I wandered outside to have a cigarette. I walked my property nervously, making circuits around the house trying to figure out how to handle Russ. Here's the thing: I knew I had to lay down the law, but if I came off too heavy-handed, Russ would react badly and that would give Travis a world of worry. I had to promise myself to take a soft approach. I stood and finished a third cigarette and looked at the west side of our home. The driveway that led to our garage ran along that side of the house. The brown brick was scuffed and streaked with black paint from Rusty's pickup truck. God knows how many times in the last year he'd driven in late, and drunk, and scraped his truck along the side of the house. I wondered where the hell I'd been, why I hadn't noticed it. I had a hunch that I was acting on all of this too late, and it was an ugly feeling. It felt like I was being watched, and I wondered if it were Wanda's eyes upon me, assessing me, shaking her head from wherever she was. I was trembling by the time I went back inside and took my position on the couch in the front room to wait for Rusty. Travis wandered halfway downstairs and said goodnight. When he'd shut off the lights upstairs I took down a bottle of rye and a shot glass. I wasn't about to start again, not regularly, but I needed a sharp one to calm my nerves.

Rusty got home at shortly after midnight. He looked sober as he hung his coat and kicked off his boots. He switched on the light and jumped when he saw me sitting there. He studied the table for a moment, acknowledged the bottle, and set his cocky stare on me.

“Thought you'd given that up,” he said.

“One or two won't hurt every now and again.”

He didn't respond. He walked past me slowly, on guard, as if I might jump up and take a poke at him. I wanted to tell him that a whisky once in a blue moon was small potatoes compared to running around with local thugs and getting so drunk you couldn't steer a truck down a sixty-foot driveway. But I stayed low-key because he seemed to have his act together at that particular point. I asked him to join me for a shot. He flashed a phony grin.

“You want me to sit and drink with you.”

“Just one, I want to talk about something.”

He fetched a glass from the cabinet and poured himself a short one.

“So, shoot.”

“Where've you been? You have a good night?”

He downed the whisky in one gulp and closed his eyes.

“Okay, old man, you're sitting here waiting for me with a bottle in front of you, you're still up at ten after twelve, and you're all cordial and pleasant, like the fucking Avon lady. You wanna tell me what's up?”

“Well, your brother is going to be talking to some Junior B scouts. What do you think of that?”

He tipped the glass right up, his tongue searching for the remaining drops.

“It doesn't surprise me. I think he could play B no problem.”

“I'd like you to help him, Russ.”

He rolled his eyes.

“Help him? Hey, I quit years ago. Haven't been on skates for five years. How can I help him?”

“I don't mean the hockey part. I was thinking more like just being there for him. He looks up to you, Russ.”

“Well, in case you forgot, I was in the car with you earlier, on the road to that game. You decided to stir the shit.”

I don't remember all of what I said next. But I lost it and said a mouthful. The boy knew how to push my buttons. He knew how to dare you to try and have a regular conversation with him. I stood and whipped the shot glass against the wall. I told Rusty that maybe he could help his little brother by setting an example. For starters, he could stop hanging out with criminals and quit making me feel like a guest in my own home, like I needed a fucking passport to walk in the front door. I told him that I lost my wife, that I knew and loved that woman for years before he was even around, so lose the attitude, the air he put on that made me feel like his was the greatest loss, the sharpest grief. Russ stood when I'd finished. He gritted his teeth and said, “You lost her because you ignored her. You put more value on that pathetic, rundown, backwoods gas station of yours than you ever did on her. She wanted out of this dump long ago. But she walked on eggshells around you all the time. That's what killed her.” He went to the front door and snatched his coat from the closet.

“Don't you drop a cheap shot like that and then walk out of here!”

He tugged the coat on and looked at me like he was challenging me. We'd fought before, back when he was about Travis's age. I damn near knocked him out, but he put up a good fight — he had the heart of a lion when it came to fisticuffs, and I doubted that I could clean his clock nowadays. He stepped towards me.

“Mom's heart failed because it had to be big enough to do the job of your heart too, old man. And you'd figure that would leave you with a lot of time to make some decent choices. I mean, what the fuck did you think the township was gonna do with that road? Everyone knew that factory was coming. Everyone knew that major changes were on the way. Man, you sit down at that greasy restaurant often enough with that blind buzzard Gus and that fat loser postman, gossiping like old women. No scuttlebutt ever reached your ears, old man? Or did you just have your head up your ass as per usual?”

I followed him outside. Travis yelled from the top of the stairs, told me to back off, just let him go. But no one talks to me like that, insults my friends and takes the piss out of my hard work. I reached Russ's truck before he could pull the door closed. I wedged my arm in there and got in his face.

“Get off the truck, old man.”

“You come out here and apologize for what you said.”

He shoved me and I fell backwards into some deep onion grass. The back of my head hit the dirt pretty hard and I got a lung full of his exhaust as he accelerated down the drive. So I sat up and coughed, eventually stood and brushed off my damp overalls. Travis came out in his slippers. He stood stock still when he saw me. He cleared his throat. I could hear the fear in his voice.

“Did he hit you?”

“Naw, he just shoved me. I wasn't ready for it and lost my balance, that's all.”

We went back inside and Travis flopped down on the couch. He sat with his head stretched way back and his forearm across his eyes, like he was exhausted. I sat on the arm of the couch. We just stayed there without saying a word. Eventually, Travis broke the silence by sitting forward and staring at the booze.

“Jimmy Piller's father quit by going to AA over in St. Catharines, you know,” he said.

I was taken back by this. I put the top back on the bottle, which only had a couple of ounces left in it.

“Art Piller was a hopeless drunk who kept losing jobs and failing his family. He had no choice. I quit without going to any meetings,” I said.

Travis shifted around and said, “Can I tell you something, Dad?”

“Sure, you can tell me anything.”

“Well, Rusty says that when he was way younger, like when I was three or four and he was a boy, you used to drink and yell and carry on. He said you were scary, says he remembers it.”

“I used to hit the drink pretty hard at times, yeah.”

“He says that Mom always worried that you'd slip up, go back to it.”

I didn't like where things were going. Rusty had a way of twisting things to suit his needs. And by the sounds of it he'd been filling Travis's head.

“You know, Travis, your big brother tended to suck up to your mom, build her attachment to him, and then use her trust and loyalty to get away with things. I remember one time when he was just sixteen he'd spent the day with her crushing tomatoes for her homemade sauce. That night he took off in a Mustang that I was reconditioning over at the garage. He only had a learner's permit at that time. He only took it for ten minutes, went racing down towards the sixth concession. When he came home I let him have it. A careless thing to do and everyone knew it. But your mom stepped in and told me to cool off, that nobody got hurt, the car was fine, Russ had been helping her all day, and blah, blah, blah. And I remember he stood off to one side while she spoke. I can remember the exact spot in the kitchen where he stood because he had this wicked grin on his face. He loved the way he could manipulate things.”

Travis chuckled nervously at the story. And then he apologized for bringing up the past, but I could see his young eyes were brimming with questions. And I could just about hear the sort of shit Rusty had been feeding him. I sat on the coffee table directly across from him and said, “I've done some things, said some things I'm not too proud of, Travis, but I never hit your mom. A man that hits a woman is the lowest of the low. Let me ask you something, is that what Rusty told you, that I hit your mother?”

Travis wouldn't look at me. He pulled his shoulders back and did some neck rolls, sighed and said, “No, not exactly, but he kind of hints around it. I think that he wants me to believe that.”

I could hear the refrigerator motor running in the kitchen. The clock on the mantle seemed louder than ever as it snapped away the seconds. My mind was quiet except for the doubt, which sat in there like lead. I wondered where I'd gone so wrong that my eldest boy had started what seemed like a campaign against me, telling Travis shit like that, leading him on. I also had to wonder if I had ever slapped Wanda, wound up and clobbered her in the middle of a drunken rage. We'd had family talks long ago, and those days were supposed to be water under the bridge. Yeah, I used to go off now and then, under the pressure of running a business, making ends meet. But I don't remember raising a hand to Wanda. When I'd eventually quit the booze, I even asked her directly. I wanted to know if during a drunken binge I'd ever hurt her. She'd said it didn't matter now. She smiled faintly and said that I'd usually been too drunk to hurt a mouse. She wanted to move on and was happy with my commitment to turn over a new leaf.

I got up and took the whisky from the coffee table. I asked Travis to follow me to the kitchen. I stood at the counter and uncorked the bottle.

“I don't need this stuff. Since your mom died I've had a nip here and there, but I don't need it. I want you to play Junior B. And if this is on your mind, well then, I want to put your mind at ease.”

I held the bottle up nice and high and poured what little remained down the sink. Travis beamed at me. He watched the whisky fall in a thin amber stream and just kept on nodding his head.

Heavenly Father, I thank you for my church family, for their love and support, their kindness to me, a kindness that is helping me to heal. I look forward to seeing them this evening.

Lord, I hold up Grant to you, ask you to walk with him, strengthen him as he starts back to work. Father, you know the dangers and difficulties that he and the others face, and I ask that you protect him, protect all of them. I pray that you will allow Grant to feel your Holy Spirit, to know in his heart of hearts that you are working in him, calling him to you. He needs you, Lord. He needs to know that you love him and that you'll welcome him when he's ready to give his life over to you.

Help Grant to conquer his fears, to overcome the hate that resides in him. Help me to be all that he needs. Help me to bring him to you. He's hiding, Lord. He's hiding the same way that I did before you found me. Let him see your Son. Let your Son's pain become his peace. In His name I pray. Amen.