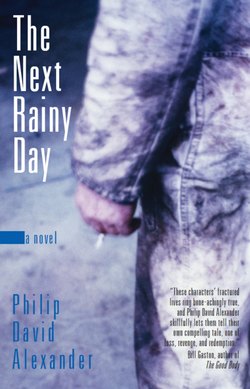

Читать книгу The Next Rainy Day - Philip David Alexander - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Grant McRae

ОглавлениеGrant McRae had been fighting nerves in his belly. He'd decided to keep his mind and hands busy in the garage, cleaning up, rearranging his tool bench, sweeping the floor, and hanging the snow shovels on some giant hooks he'd installed so they'd be out of the way until winter. He knocked a dustpan against the huge rubber garbage bin, dumping a handful of dust and grit he'd swept from the concrete floor. The phone was ringing inside the house, and he walked over to the garage wall and listened. It was his line downstairs in the study, so he dropped what he was doing and hightailed it into the house and down the stairs two at a time. He snatched up the phone and confirmed his hunch, smiled wide as Danny Cook's voice came loud and clear from the other end.

“You busy?” asked Danny.

“No, I was just passing time.”

“Butterflies in the gut, I bet.”

“Yeah, sure, a little.”

“Why don't you swing by for a beer? I've got six Heineken in the cooler with our names on them.”

He signed off with Danny and knew he should go upstairs, grab a shower, and head over for a beer and bowl of pretzels. Instead he stood with the phone in his hand, very still, aware that his legs were quivering. He pressed his code and waited for his messages. As a computerized voice came on and began its routine he wondered when he'd erase the message. It only did him good for a few seconds, and then he endured the minutes or hours that came afterwards — an assortment, a fusion of emotions that mostly left him crippled with sadness or consumed with anger. But the message lured him. He knew damn well he couldn't put the phone down and walk upstairs. And the chances of him erasing it were slim, if not nil. This was his huge secret. A ghost that he could summon with the push of a few square buttons. No one else knew it existed.

“To listen to your saved messages, press nine.

“First saved message.”

“Oh, hey Dad, it's me, Adam. [Laughter in the background and another boy's voice saying, ‘He knows it's you, bonehead.'] Dad, Terry and his mom were just telling me about that new shopping mall that just opened. They've got rides inside of it. Terry went on a roller coaster, well, a small roller coaster. [More laughter and the other boy's voice:‘It was called the Cobra, you spaz.'] Yeah and they've got bumper cars there, too. It's all inside the mall, is that cool or what? So I wanted to call in case I forgot to tell you. Maybe we can go there sometime, like on the next rainy day or something. Okay, Dad, see you later. Terry's mom's making us pancakes in the morning. Bye!”

“To erase this message, press three. To save it, press four.

“Message resaved.”

Adam had left it what seemed like years ago while sleeping over at his friend Terry's house. Terry's place was only around the block, but Adam had seemed apprehensive about going. Both Grant and Rachel had said he should go, stay up late, watch TV, eat popcorn, sleep in sleeping bags in Terry's bedroom, have fun. Adam had called them that night on the main line to say good-night at around ten. And then he had called on Grant's line just prior to midnight. Grant knew it was his son's way of saying a couple of things. Perhaps that he was a little nervous about being over there, laying his head down to sleep at someone else's house. And also that he missed his folks and wanted to call just once more. When Grant had walked over to meet Adam the next morning his son was brave and nonchalant as he finished up a stack of pancakes. He told Terry and his mother he couldn't wait to sleep over again. As they walked home, Adam made no mention of the extra message he'd left, so Grant didn't pursue it.

Grant sat down on the floor cross-legged with the phone still in his grip. He rocked slightly, a movement that somehow helped him when he felt incomplete. He snorted and gulped. He could feel tears on his face, tasted them at the corner of his mouth. He knew that he had to keep it together. He was walking into a whole different world tomorrow. There would be no room for emotional speed bumps like this, no time to be tangled up in strands of alternating sadness and rage. He grabbed a tissue from the box on the shelf and wiped his eyes. Maybe a beer and a talk with old Danny was just what the doctor ordered. Danny had been retired for over a year and had made a point of keeping in touch even when Grant had drifted and pushed people away. Grant would be in his study with the stereo on, alone, in darkness except for the green glow from the tuner and CD player. He'd hear the phone ringing faintly over the music pressing in his ears. The phone would ring eight times and then fall silent as the voice mail picked up. And then it would ring again and again until Grant bolted up and shut the music off and answered. Danny Cook would be on the other end. They'd talk, sometimes Grant would break down and spill his guts. Danny would listen and never try to tell Grant how he should feel or what he should do. He listened and then tossed out a word or phrase of encouragement. Grant would grab that and focus on it, take it to bed with him and sleep on it. Danny Cook was a retired policeman with few friends, a beer belly, and an obsession with retirement. He saw the world in black and white and cared little for anything apart from his immediate family, fishing, and cold beer. But Grant received comfort and a sense of connection when he listened to Danny. When they talked there was at least a distant nexus with the regular world. The regular world where people had healthy children, went to work, and returned home to eat dinner and help with homework. A world where the largest worries weren't really worries at all. Can we afford Disneyland this year; will I get that promotion; will interest rates really go up that high? That world was gone. It had disappeared not too long ago under a frigid November sky.

Grant stuck to the side roads as he drove to Danny's place. He was in no particular hurry, and he rolled all the windows down, turned up the radio, and stole a glance at a couple of women walking in short shorts, pushing strollers under the hot sun. “Yummy mummies” Danny Cook would call them back when they were working a community patrol car together. Grant thought about that as he drove, working a patrol area without Danny's wisdom and company. Radio chattering, coffee balanced on the dash, notebook entries, incident reports, traffic points, all of that. He grasped it and enjoyed the familiarity of those small things, the nuances specific to any job. As he got closer to Danny Cook's home the sadness faded, and he felt the sun coming off the dash and heard the music with greater clarity.

Grant pulled into Danny's driveway and tucked his Jeep in behind Danny's Caddy. Danny had obviously waxed the thing again; it damn near blinded you to look at it. Grant smiled, felt pleased for Danny Cook. He'd taken his daughter Gwen up on her long-standing offer to move in with her and her two daughters. Danny loved those grandchildren with all his might, with every inch of his great big Irish heart. And the arrangement had been working well, Danny and his daughter getting along famously, helping each other out and raising the twins. It seemed like a rewarding way to spend retirement.

Danny answered the door with a big grin on his face. The man could simply smile and you felt that all was right with the world. Grant followed him down the hallway into the kitchen and out a set of French doors to the deck. Danny excused himself to fetch a couple of beers, and Grant sat in a Muskoka chair and inhaled the sweet scent of the Cooks' huge flower garden below.

“That ought to hit the spot,” chuckled Danny, handing Grant an ice-cold bottle. Grant took a sip, wondered how Danny always kept the beer so damn cold, an ice particle or two in every sip. Danny positioned himself across from Grant.

“Hide your eyes, McRae, it's too hot out here for this thing,” said Danny. He yanked off his T-shirt to expose a typical retired cop's upper body: strong and burly, with the gut extending much further out than the chest. The cab forward design, as Danny called it. Danny took a healthy chug of beer and wiped his mouth with his forearm.

“Well, one last brew before you get back to it, huh?”

“Yeah, by this time tomorrow I'll be riding shotgun with the one and only Owen Crews,” said Grant.

“That's confirmed? You're going over to 14 Division, for sure?”

“Yeah, I talked to Inspector Laird yesterday. He's ready for me, said I'd be partnered with Crews for the time being.”

Danny Cook shrugged, said, “You're okay with that, aren't you?”

Grant hadn't done much thinking about it. That fact that he was actually going back to work had been a big enough bite to chew on. He was more concerned with how he'd handle it, how he'd perform.

“Well, I would have preferred to go back to 24 Division. I mean, it's where I started, our old stomping grounds, but let's face it, it's not a huge department, so it's not likely to be all that different, right?”

Danny leaned back and wiped the sweat from his beer. “Hey, 14 is growing, getting as busy as 24. And you knew that Laird would want you there, which might not be a bad thing, considering,” he said.

“I just hope that he doesn't want to talk about it all the time, you know? I hope he doesn't expect us to bond: brothers in turmoil and grief. That's all I need.”

“Well, Grant, he's a front-runner for Chief of Police once Glendon steps down. Deputy Van Heusen is too old, doesn't want the job anyway. So, my money's on Inspector Laird. Being tight with the future chief? Not exactly a career-limiting move in my opinion.”

Danny laughed when he'd said this and held up his beer.

“Cheers, by the way,” he added.

They clinked bottles and both looked off the deck onto an almost blue-green lawn.

“What do you know about Owen Crews?” asked Grant.

“Crews? Super Cop? Nothing outside the usual gossip really. I mean everyone knows of him. He's young, but also an old-fashioned law and order type, which doesn't bother me one bit.”

“I get it, but then I don't, you know? You'd think they'd have put me with someone like Singh or Moretti. Why Crews?”

“Well, if you were with Singh, you'd get stuck doing all his paperwork for him, on account of his hatred of anything that requires ink. Moretti would drive you nuts with his constant talk about renovating that fucking house of his. Take your pick,” said Danny.

“I guess you're right.”

“I usually am. Well, I was wrong once. Thought I'd made a mistake, but hadn't,” said Danny. He laughed at his own joke and told Grant to lighten up.

“Look, Grant, Owen Crews is Laird's boy. He just got made up to training officer, so Laird obviously sees something in him. Like I said, being on the next chief 's good side isn't going to hurt you. I'll bet Crews, despite his past lapses in judgment, makes sergeant within two years. Shit, McRae, don't make the same mistake I did and wind up a beat cop for thirty years. If Laird takes a shine to you and Owen Crews is going places 'cause he's in Laird's back pocket, well, get in there, ride in his slipstream, and take whatever opportunity comes your way.”

“Yeah, yeah, I hear you. You're right.”

“I usually am. Well, I was wrong once . . .”

Grant joined in and they finished the sentence in unison. And then Danny Cook got up to get two more beers out of the cooler.

Grant drove home just before the dinner hour. Danny had asked him to stay. He was heating up the barbecue and defrosting some chicken to feed “his girls” when they arrived home. Grant had declined. He didn't want to get in the way, interfere with family plans. Besides, it was tough being around Danny Cook's grandchildren. They were ten years old, happy, bright, well-behaved kids. And while that should've made them a pleasure to be around, for Grant McRae it was difficult to sit and watch them laugh and run and do all that kids do.

Rachel's Toyota was in the driveway when he arrived home. He backed his Jeep up beside her car and noticed a portion of the hedge that he'd missed when he'd trimmed it earlier that week. He opened up the main door of the garage and grabbed some pruning shears, wandered over and clipped back the fine branches. He always hated coming into the house after not seeing Rachel for a few hours. It always seemed to him that she observed him very carefully for the first few minutes. Conversation was wooden, and no matter how hard they both tried, it came out sounding rehearsed. He ran out of hedge to trim, so he unwound a few feet of garden hose, attached the sprinkler, and turned on the water.

The house smelled of onion and spice when he finally walked in. A preacher was whining on the radio, and he could see Rachel moving about in the kitchen.

“Hey, Rachel, I'm home.”

She came into the front hallway with an apron on, mixing spoon in one hand.

“I got your note,” she said. “How's Danny doing?”

“He's swell. You know him, happy-go-lucky. It's really working out well with his daughter and her kids.”

“I've got a meatloaf in the oven. I have to eat soon because I have to be at the church at seven-thirty,” she said.

“Sounds good. I'll join you.”

She'd turned and walked back toward the kitchen, but stopped and said, “You'll join me?”

He felt his shoulders tense up. He had to be careful these days, watch how he said things.

“I meant that I'll join you for some meatloaf. After that I'll go for a run, come home, grab a shower, and listen to some tunes downstairs. I should make it an early night.”

She crouched to pull the oven door open.

“Oh, I thought for a minute that Danny had convinced you to come to a Bible study.”

Grant walked through the kitchen and started up the stairs. He was going to ignore Rachel's comment at first, but stopped halfway up and said, “Why would Danny Cook convince me to go to church? He's not religious.”

She was at the bottom of the staircase with oven mitts still on her hands.

“No, but he's spiritual. His father was a deacon in the church over in Belfast,” she said.

“How do you know?”

“He told me.”

“When?”

“I don't know, maybe a month ago. He'd called here for you when you were out. We chatted, and he told me all about his father.”

Grant wanted to just carry on, head upstairs, and throw on his gym shorts and a tank top. He was back into work within twenty-four hours and didn't want an argument with Rachel. On the other hand, he wondered if she'd been Bible-thumping to Danny on the phone.

“I hope you didn't preach to him or anything,” said Grant.

“No, no. I forget how it came up. Anyway, supper's ready, did you want Caesar or tossed salad?

“He called on our line?”

She sighed loudly, said, “Yes, Grant. He had tried calling your line downstairs but you weren't there. He just thought maybe he could catch you if he called on the main line.”

It started as soon as he picked up his knife and fork. He knew she was doing it even as he slid the knife through a wedge of moist meatloaf. He took a bite and looked at her; he could feel pangs of anger that seemed to surge as he chewed his dinner. She always watched him like she was expecting something to happen, a sudden conversion, Grant McRae on his knees speaking in tongues, calling out to Jesus. It was almost better back when they argued about her new beliefs and her evangelizing to anyone who would listen for ten seconds. Now there was just silence on the whole topic of God and Christianity: an unspoken agreement had been quietly enacted and allowed for a peaceful co-existence. But every now and then Rachel would test the waters. And it usually started with the thoughtful stare. Grant put his fork down.

“Rachel, what is it?”

“Why are you so angry?”

“I'm not angry. You're staring at me like there's another one of your sermons on the way.”

She sipped her tea again and shook her head.

“No. I was wondering if you'd listened to that CD I gave you, though.”

“I haven't had time, besides, I don't think I'd like them.”

“How do you know that? They're great musicians, and the lead singer's voice, it's like he really feels every word he sings.”

Grant got up and took a soda from the fridge. He opened it and remained standing.

“I don't want to listen to religion when I listen to music,” he said.

She got up as well, tilted her shoulder to squeeze by him.

“Suit yourself, Grant. I bought it to cheer you up, that's all.” Grant watched her back down the driveway and drive off to the church. He looked out at the street where he'd lived for eight years, noted how the skinny saplings at the end of each front lawn had started to fill out, actually looked like trees. It was the type of place where nothing much ever happened. He'd sensed that when they'd bought here, a safe and tidy little subdivision where you could raise your child and socialize with like-minded people. All bets were off now. He felt like a stranger. Felt people's eyes upon him when he cut the grass or washed the car. He watched Rachel signal at the top of the street and turn right to catch the main road. She'd go and talk and read the Bible and do whatever it was they did until ten o'clock or so. And while he was slightly envious about the apparent peace she'd found, he didn't want to get involved. It seemed cult-like to him. The way they took you in and embraced you without knowing a thing about you. Within weeks they'd have you in this world of Bible study, laying on of hands, Sunday morning service, social group followed by Sunday evening service. And when you stepped into that world you were in a bubble where the elements were all pure and every question had a definitive answer. Answers backed by Christian radio, books, coffee mugs that declared love for Jesus, bumper stickers, and music — like the nonsense Rachel had left on the kitchen table for him two days ago. The price tag was on the back of it. She'd gotten it from a place called Good Shepherd Music & Books. Grant flipped it in the air and kicked it down the hallway. Its plastic cover broke after it skidded along the floor and hit the base of the front door. He decided he'd better pick it up and put it somewhere. Rachel would be angry if she found out.

Grant went outside and backed his Jeep into the garage. He got out and caught a glimpse of some tiny training wheels hanging behind the shelves where they kept the recycling boxes. Grant thought that Rachel had given them to Goodwill. And he wished to hell that she had. He felt something coming. It was on him before he could deflect it.

You were out with Adam and he was riding his silver and blue bicycle with the training wheels still on. You watched him ride away, bombing along the sidewalk. The training wheels were barely touching the ground. You ran after him and told him that you had an idea. His eyes lit up and he jumped up and down in the saddle when you told him the plan.

At the park you took a small wrench from your pocket and removed the training wheels. You held on to the handlebars while Adam pedalled. There was nobody on the path and you jogged alongside of him, reciting the same mantra:“Sit straight on the bike, don't look at the front wheel, just watch where you're going, use the handlebars to keep balanced.”

He giggled and yelped when you let go. You watched him wobble and correct himself as he rode away. He went quite a distance on his own and then used the brake, put down his right foot for balance like he'd been riding for years. He looked back and waved. You felt an incredible rush of pride and sadness. He turned the bike, adjusted the pedal, and started back to you, a few wobbles and tips as he came back, but he made it.

That night you told Rachel all about it once you'd tucked him in. She fought tears when you whispered to her about what you felt deep in your chest as his little legs pumped and you let go, watched him ride away.

It's been a long time since you've talked to her like that.

As this comes to you it's incomplete, like many of the others. What's missing is little Adam's real face. The face you see here isn't his. It's white and powdery and it unnerves you.