Читать книгу The Next Rainy Day - Philip David Alexander - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

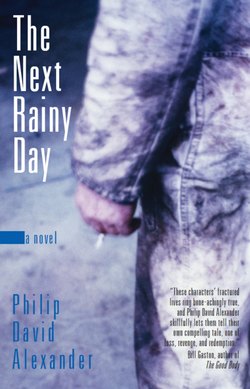

Bert Commerford

ОглавлениеTravis burned through his tryouts and was signed by the Stoney Creek Spirit of the Golden Horseshoe Junior B League. Man, was I proud. When Travis got word that he'd earned a spot on the team, we jumped around and screamed like a couple of children. I'd never seen him so wired, and it was amazing to see the lift it gave him. The atmosphere in our house was buzzing, like it used to when the service station was doing well, Wanda was alive, and my boys were still children.

The whole thing gave us all such a shot in the arm. Even Rusty seemed to calm down and act a little steadier. Things still weren't great. We'd had another argument around a week before Travis's tryouts. Russ had told me he'd been doing some work for the Street brothers, legitimate stuff where they distributed goods for “small industry.” I told him that was fine, but if I found out he was dealing drugs or stolen property, I'd boot him out of the house. He went wild, shouting and carrying on, bringing up Wanda and how I did the same to her, lent my ear but never really listened. I left the house and walked over to the service station to start working on getting our snowmobiles ready; the air had turned cold and dry and it smelled metallic, which meant that snow wasn't too far away. I wanted to get away from Russ.

The arguing and bullshit had a way of tiring me out. There was knot the size of a fist in my belly for Trav's first game. The arena was new, more seats, more electricity in the air. The players seemed bigger, faster, like gladiators. The jerseys they wore were bright, real vivid, just like the pros. I was a total wreck, chewing my nails, waiting for the opening faceoff. There was no waving at the players. I noticed that right away. I spotted Travis, wearing number 9, but he never scanned the stands to look for me. This was a different thing now. We'd never come out and said it, but we both knew that he was capable of making a dent, maybe heading to A and who knows how far from there. Yeah, I know, a hundred thousand other dads think their lad is going to be putting on a Maple Leaf jersey by the time they turn twenty. But Travis had speed and hands like a surgeon, and he was playing hard, determined to make a real go of it. When I look back on his games, I see him moving with incredible speed, doing things with the puck that were beyond his age and level. I recall that his ice-time went from four or five minutes a game to about twenty minutes pretty quick. And he was racking up assists and playing good two-way hockey. He only scored two goals, but he knew how to pass and control the boards. So I don't think that all his potential was just in my mind.

During that first Junior B game, Rusty finally showed a few minutes into the first period. I saw him walk in and stand near the Zamboni doors. When there was a break in the play I whistled and he came up and sat with me. He carried himself a little differently that night. A swagger in his step that I didn't like. It wasn't until he sat his ass down that I saw his face had been cut and he had a mild shiner on his left eye. I checked out his hands: his right was swollen around the bottom knuckles, fresh cuts on his fingers. He looked pale, which wasn't too uncommon with Russ; his skin was fair like his mother's.

“Looks like you were in a pretty good waltz,” I said.

He rolled his eyes and said he didn't want to talk about it. He asked how Travis had been playing, and I told him that he'd only been on for one quick shift. I wound up watching Russ as much as I did that first game. He was cocky, the big man on campus. Just the look in his eye and the black leather jacket and thin leather gloves he'd taken to wearing, the backwoods hit man. He stepped into the aisle to get us a Coke and some guy had to pull up to avoid bumping into him. Russ looked at him, just begging for trouble. I went to speak up and tell my boy to back off, but the guy just shrugged his shoulders and let Russ pass in front of him. I watched him head down to the concession stand. He was running with the Streets, getting banged up in the process, walking around like some fucking cowboy. He knew how to manipulate a situation, too. So I don't think his potential, or lack of it, was just in my mind either.

It was a Monday morning, a little light snow had started, and the sky to the west was getting dark and looked to be churning, headed our way. I had dropped Travis at school and decided on two eggs and some bacon down at the Copper Kettle. There wasn't much happening at the station — I had to get used to the idea that my business had been reduced to a hobby, something to fill in the time here and there, maybe provide a little pocket money when a regular came in for an oil change or tune-up. I have to admit that as I drove to the diner I felt pretty good about things for a change. Travis was doing what he wanted, and there was this hope — yeah, a long shot but still a hope — that I might have a pro hockey player for a son. I had some money in the bank, enough that I didn't have to sweat about things for a while. Rusty was next. I needed to find a way of reaching a ceasefire with him. That's about as much as I could ask when it came to Rusty.

You can't beat a place like the Copper Kettle on a chilly day, when the snow is falling. Don Bertram Jr. ran the Kettle. His father had built it in the sixties and decorated it with copper light fixtures, which were polished weekly. It had the familiar Formica tables and counter that you find in most diners. The chairs were finished in thick burgundy vinyl. The menu was simple, but they served big portions and brewed coffee that you could smell in your clothes when you got in your car afterwards. Don was in fine form that morning, cracking jokes as he cracked eggs and mixed pancake batter. I said hello and he told me he'd make my usual, unless I had any objections. His daughter Grace worked the tables and smiled, pointed to the booth where Gus and Will Makepeace were sitting, smoking and likely sipping their third or fourth coffees. I joined them and they gave me the tenth degree on Travis. They were thrilled for him. My mood continued to climb. You'd have sworn it was their own blood they were talking about. Will ran the equestrian centre to the north of Battleford, and he always had a horse story or two. His daughter Angela had just missed making the national equestrian team, so he knew what it was like to have a kid in a competitive sport.

I wiped the last of my egg yolk with some rye toast and settled back to drink a second cup. Will excused himself to get back to work, and Gus and me shot the shit and caught up. He told me that the township had approved a small subdivision up near the new Crandy Manufacturing plant. His daughter was thinking of moving up there because her husband had been offered a job with Crandy once the plant opened. Here's the thing: I had no hard feelings at that particular point. My anger over it seemed to surge and then kind of wane, plus this was Gus, an old friend who'd give you the shirt off his back if he had to. So I told him to wish his daughter and son-in-law well for me. Baxter walked in, dusted some snow from his coat, and dropped his mailbag near the coat rack. He sat with us and warmed his hands around a cup that Gus had reached over and poured for him. He told us he still had half the mail to deliver, but needed some coffee and toast. He was a little nervous or something, not his easygoing self. After we'd done the “Hi, how are you” routine, Baxter said, “So, I've got some news.”

Baxter's news was usually good and trustworthy. People in small towns tend to befriend the mailman, especially a jovial type like Bax. Gus and me leaned in, ready for the dirt, but Baxter looked at Gus and then over at me.

“This is, ah, sort of touchy information that has to do with your oldest boy, Bert.”

I put down my coffee and lit a cigarette. Gus said, “You want me to go over to the counter and flirt with Grace? I can if it's private.”

I told him to stay put. They both knew Russ. They both knew the trouble I had with him. Three heads are better than one.

Baxter had been on his rounds the previous Friday and got talking to Eddie Taft, an old-timer who lived right off the main road in town, just around the corner from the diner. Taft was fixing his snow blower and bragged to Baxter about the ratchet set he was using. He told Baxter he'd bought it from the Street brothers for $25. He went on to say that the Streets had a load of tools they were planning to sell down in the city, but they sold a set to Eddie Taft as a favour because Eddie plowed their laneway for free now and again. Baxter said that Eddie seemed proud, like it was an honour to have a couple of thugs doing him favours. Baxter took a look at the ratchet set Eddie was using. He asked Eddie where he thought the Streets had gotten it. Eddie said who gives a shit, for $25 he wasn't asking questions, this was a damn good set of tools. I felt my gut just sink as I listened to Bax. I snubbed my smoke in the ashtray and looked him in the eye.

“Mine?”

“Yeah, I've gotta believe so, Bert, it was made by Proto Tools. I remember how you used to buy those sets at their big sale every year. Plus Eddie Taft said that Russ was in the Streets' car when they dropped by to sell it. I don't mean to be a wind-bag, but I know those tools were from your shop, Bert. Eddie looked damn uncomfortable when I told him so. Shrugged his shoulders and said, ‘Well they're mine now, Baxter, and I'd sure appreciate it if you kept this to yourself.'”

I let the news roll around in my head for a few seconds. I knew that Baxter wouldn't have mentioned it if he weren't certain Eddie Taft had bought property that was stolen from me. Gus spoke up and said, “How many spare tools do you have, Bert?”

“Quite a few. I sold some, but there's a load still in the basement at the station. I thought I might put an ad in the paper in the spring, make a few bucks from them.”

“Looks like Rusty and the Street boys beat you to it. Bastards,” said Baxter.

“Did Russ ever ask you about them tools and maybe you forgot?” said Gus, all hopeful, wanting to believe that maybe Rusty wasn't lifting property from his own father.

“Never. But I'll be damned if I'm gonna sit back and let him sneak around pulling shit like this,” I said.

“Call the police on him, teach him a lesson,” said Bax.

My gut was gurgling away by that point. I could pretty well feel my ulcers dancing around in there.

“You know what guys, I just might. For now, I'm gonna hit the road and have a poke around downstairs at my old gas station.”

When I got to the station I felt pretty strange. For starters, I'd let the gas wells run dry and the pumps were wrapped with thick, black tarps. There was no use in buying more gasoline when Dunn Road had been closed and traffic diverted. I'd had the odd car ramble by looking for gas, but word soon got out that I was dry. The place looked like part of a ghost town, gray and deserted. I went inside and stood for a second, took in the silence, observed the stillness inside the two service bays. Those bays were hopping at one time, always cars on the hoists, Vic and his apprentice and me working away. Russell or Kenny the part-time kid answering the bell when someone drove across the hose and up to the pumps. The place gave me the creeps now that it was so quiet. There was water dripping somewhere, but other than that it was like a fucking tomb in there.

I went down the narrow wooden stairs to the basement. It was just a big rectangular room with a few steel shelves and rusting old cabinets where we'd store extra cases of oil, fan belts, and other supplies. I kept spare tools down there. I was a bit of a collector, I guess. I'd built up a decent little stockpile. I walked to the cabinet where I kept the ratchet sets, wrenches, screwdriver sets, stuff like that. I closed my eyes as I opened the door.

Here's the thing: I never kept inventory. I could glance down there and tell if we needed replenishments. And as I stared into that supply cabinet I knew I'd been screwed. There was shit missing. It looked pretty sparse in there. It took a good hard swallow to chase the heat back down my throat. It made me ill to think that Rusty would steal from me. And that maybe those Street brothers had been with him.

I went back up to the office and sat down behind the old desk where I'd once been the man in charge. I sat there until dusk, watching the house. I saw Travis come home and then leave with his gym bag under his arm. He waited at the end of the drive until a kid in a white Toyota picked him up and they sputtered off. The kid's car needed a muffler, and I made a mental note to tell Travis to invite the kid over for a free repair job. I didn't turn on the light once darkness fell. I smoked and watched the glass desktop, the burner on my cigarette lighting up my fingers and face. I recall my mind that night moving in a different direction. I was less concerned with why things happened, more concerned with what I would do about it. This was my boy who'd done this to me. Stealing from his own father after all the grief we'd already taken on the chin. That's something only a scumbag would do.

I called the police. It used to be, way back when, that you could ring straight through to the police station. That had all changed, and I had a hell of a time finding out who was on duty. I knew most of the coppers pretty well. But the OPP had this big central dispatch by that time, and the lady kept on asking me:“Do you need to see an officer or not, sir?”

And I kept on saying:“Depends on who it is.”

Finally I got connected to the shift supervisor, who put me on hold to go and find out who was on duty.

About an hour after I'd picked up the phone, Big Rich Franklin pulled up in his cruiser, parked alongside the dormant gas pumps, got out, stretched, put his hat on, and wandered into the office. I didn't know Big Rich as well as some of the others, but he was a decent guy, used to be with the Windsor police. He was no dummy and he seemed like a good, honest cop. He asked right off if I'd had a break-in. I told him no. And then he sat down across from me and took out his notebook. I let him in on a few facts, some background on Russell Commerford. And then I told him what Baxter had told me. He scribbled in the notebook; his big paws moved pretty gracefully when he was writing. When I was through talking he didn't say too much at first. He scratched at his wide forehead with his pen, finally said, “Did you mark or engrave the tools you kept down there?”

“No.”

“Well, that's okay. I could go over to Taft's place, ask to see this tool set. I could bring it back over to you. If it's yours I could go and get Russ, talk to the Street boys.”

“What'll happen? Will Russ be charged?”

“Well, maybe.”

“In a way I want him punished, but then again I don't. Man, I don't know. He's running with the Streets. I don't want them on my property. It irks me to think they were here. I really hate them, Rich.”

Big Rich leaned back in the chair. It groaned and squeaked under his weight.

“I know that Russ is hanging out with the Streets. He got into a fight with a guy down at the Salby Tavern; word is he was trying to collect a debt for the Streets. He's wearing the infamous gloves now, too. That's the Streets' big tactic, doing break and enters and chickenshit thefts with gloves on. They're not criminals, really. Basically they're losers who dabble in crime. This is the type of crap they do, stealing tools, shoplifting, and then selling the stuff at flea markets. We could pick them up and do them for theft under. They'd get a fine and some community service. Same goes for Rusty.”

“No jail?”

“Not for theft under. Doubtful.”

“I heard the Streets had robbed banks, dealt drugs . . .”

Big Rich chuckled.

“They sold some weed when Alvin the biker was living with their old lady. He disappeared though. Probably feeding some worms and other assorted ground-dwelling creatures in a field somewhere. I don't think they've sold any weed since. As far as banks, they're too dumb to rob a bank. That takes some planning, some brains, at least to do it right, you know?”

I placed my head in my hands. I told him not to do anything just yet. He got up and looked ready to leave. He put his hat back on and said, “Listen, Bert, I realize you've been through a lot, you know, with Mrs. Commerford. She was a nice lady. And now your boy's doing this. Look, why don't you think on it? You want me to visit Taft, I will. We'll see if we can hang a theft charge on the three of them. But one thing's for sure.”

I looked at him. His tone of voice had shifted.

“What's that, Rich?”

“The Streets are jackasses, we're watching them. They'll wind up in jail sooner or later. I just hope Russ can figure out they're a waste of perfectly good space and oxygen before that happens.”

I watched him pull away. He flashed his roof lights for a split second and honked his horn as he turned right onto Commerford Road. I continued to sit there. Rich Franklin had said that Rusty had been in a fight on the Streets' behalf. That he was wearing those ridiculous gloves. I tried to feel sorry for Rusty. First of all, you don't get in a fight when you collect money, when you're strong-arming a guy. You beat the snot out of him, scare him, motivate him to get that cash and get it fast. Rusty had taken a few pops in the head during that scrap and he was wearing the marks from it. And stealing from my basement as opposed to lining up a real B&E or robbery. It all reeked of a poor punk just yelling for attention. It smacked of bush league criminals, fucking amateurs that the cops don't even consider a real threat, but watch them until they trip and fall all on their own. As sad as it was, the sympathy wouldn't come. And then the noisy white Toyota carrying Travis back from the gym pulled up. I watched my youngest boy get out, lean over, and say something to the driver. He gave the hood of the Toyota a friendly thump with the side of his fist and waved as it sped away. And my feelings for Russ dropped off the radar. I'll admit it. I couldn't bring myself to feel anything for him.

Travis sat in the kitchen, shovelling cereal and chopped banana into his face. He said he'd had a good workout and the kid who'd picked him up was named Tony Mooney, played in the same league. I told him to send Tony over for a free muffler and tailpipe. And then it was down to business. I told Travis about Rusty and the stolen tools. He put his spoon down and closed his eyes.

“Man, why does he do stuff like that? You sure those tools are missing? They're not the ones you sold, you sure about that, Dad?”

“Travis, I ran that shop for years. I know what was down there. I know that place like the back of my hand. Your brother and those Streets stole from me.”

Travis got up and washed out the bowl, held the spoon under a stream of hot water. Out of nowhere he said, “There's this girl at school, Glenda Petrie. On Friday she comes up to me, leans on my locker, and makes some small talk. After we talked for a while, she says,‘Your older brother is a sicko.'”

Travis turned and leaned against the counter. His voice was brittle. He looked worried.

“I asked her why she'd say that. She tells me that her and her boyfriend were out at Bryant Park, in his car sharing a beer, smoking some cigarettes, just kicking back. This black pickup truck comes bombing in, parks, and just sits there. After a while, it starts rocking. Glenda and her boyfriend think this is a scream so they just sit and watch. The truck stops rocking after a few minutes and the interior light comes on. Someone pitches a beer can out of the window. Glenda's boyfriend says he thinks it could be Rusty Commerford in the truck and wants to get out of there, in case Rusty spots him, you know, accuses him of spying or something. So he puts the car in drive and starts to roll, but then the door of the pickup flings open and out falls Cassandra Street, half naked, giggling away like she's drunk. Two arms reach out after her and start yanking her back in. Glenda and her boyfriend got nervous and got the hell out of there. But Glenda said that it was Rusty in the driver's seat. She saw him.”

Travis sat down and stared at the floor. I felt like I had motion sickness.

“This girl at school, she's certain it was little Cassie Street?”

Travis nodded.

“Goddamn, she can't be more than fifteen, Travis. Isn't that right? What grade is she in?”

“She's in grade nine, but I think she flunked grade two or three. That's what I heard.”

“Your brother's out of control.”

Travis looked like he was carrying the weight of the world. He had the worry gene, just like his mother.

“Yeah,” he said.

“Well, this is it. I'm gonna have to talk to Rusty,” I said.

“Yeah, but Dad, I don't want you two fighting. I don't want anyone getting hurt.”

“No one's gonna get hurt. Russell's moving out, though. We can't live like this. You can't concentrate on hockey, school, everything you've got to think about with this shit going on. If he wants to carry on like this he'll have to do it away from here. I won't condone it. If I let him stay, turn a blind eye, that's just what I'd be doing.”

Travis pushed his chair back from the table quickly.

“Man, I shouldn't have told you that.”

“Travis, what he's doing is illegal. The stealing, the fighting for those Street brothers. What he did in that truck with Cassie Street is insane; it might be statutory rape for God's sake! I know for a fact she's barely sixteen.”

“I'm going to bed. I don't feel too well.”