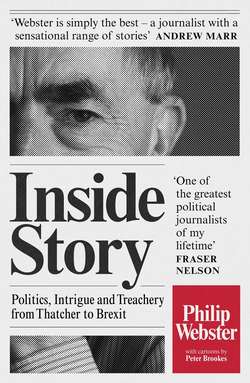

Читать книгу Inside Story: Politics, Intrigue and Treachery from Thatcher to Brexit - Philip Webster, Philip Webster - Страница 19

The Lobby Lunch

ОглавлениеEvery weekday within a square mile or so of Westminster, small groups of highly committed individuals meet in supposed secrecy at the best restaurants of the day. Usually just before 1p.m., one, two or even three political correspondents will gather at their table and plan the tactics that will play out over the next hour or so.

A few minutes later their guest – a government minister, senior opposition figure, or a powerful political aide – will rush in. Sometimes they look around nervously, hoping no one recognizes them; others, the attention-cravers, look around rather hoping that colleagues or friends will notice that they are about to eat with the political personnel from, say, The Times and the Mail.

This is the Lobby lunch, an institution that is a central part of the discourse between press and politicians. The Lobby is the collective name given to journalists who are accredited to work in Parliament and attend Downing Street briefings, as well as visiting parts of the building such as the Members’ Lobby just outside the chamber to which mere mortals are denied access. Just as in the Members’ Lobby, information passed to reporters at lunch or dinner is not attributed to the source directly unless the source asks that it should be. The Lobby system, about which I write later, is the code under which politicians and press interact.

Most of the national newspaper political correspondents are in what they call their Lobby lunch groups. On becoming a member of the Lobby, your boss advises you to join a lunch group or find a colleague of similar experience to set up your own. The rule of thumb tends to be that the more senior the group, the more senior the minister they seek to take out. That is no great disadvantage to the more junior members of the Lobby; in my lengthy experience, I found it was the newcomers to the Government or Opposition front-bench who were more likely to ‘sing for their supper’, as we put it.