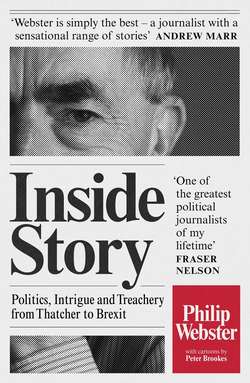

Читать книгу Inside Story: Politics, Intrigue and Treachery from Thatcher to Brexit - Philip Webster, Philip Webster - Страница 9

John and Edwina: The Liverpool Novel

ОглавлениеAt around 9 p.m. on the evening of 27 September 2002, Robert Thomson, editor of The Times, stunned his colleagues by doing an impromptu jig around the office. Thomson suffered from a notoriously bad back and his manoeuvres might normally have caused him some pain. But the editor was too excited to feel any discomfort. He had just received from me a statement from John Major, the former prime minister, confirming that he had an affair with Edwina Currie.

It was the trigger that meant a specially prepared, secret edition of the paper – replacing a phoney earlier one that had been sent out to fool rivals – could be published and a story that was to shake the political and non-political worlds would arrive at the breakfast tables. I have been told by many people over the years that it was one of those jaw-dropping stories that made them remember where they were when they first heard it. Major was seen as the ultimate grey man, while Currie had been one of the country’s most flamboyant political figures with a gift for publicity matched only by Margaret Thatcher.

It was the culmination of an extraordinary cloak-and-dagger operation that depended on the few people who knew about the contents of Currie’s diaries maintaining complete and utter confidentiality about them. It was a scheme that could have gone wrong at any point. It would be an astonishing scoop for the publishers Little, Brown and for the paper, which had paid to serialize it, but it was no good to either if the story leaked and it ran across the front pages of other papers as well.

I had been assigned the task of reading the diaries, satisfying myself that the story was true and plausible, and then assuring everyone else in the loop that it was. Further, my job would be to write it up as the main front-page story, known in the industry as the ‘splash’, and most important of all to contact John Major on the day, breaking the news to him that a secret he had lived with for much of his life was out, and getting a reaction from him if that was at all possible. That was all!

Robert Thomson was adamant that the story would not be published unless Major had been told. Normal journalistic courtesy and propriety demanded it. Whether he would confirm it, we had no way of knowing. If he denied it, we were in trouble. But getting to him was paramount. And on the night of 27 September 2002, I nearly failed in one of the most critical missions an editor has ever asked me to undertake.

The story of how it almost went horribly wrong has never been told – until now.

Robert had called me down to the office two weeks beforehand. He had been editor for six months, having joined The Times from the Financial Times. We had immediately struck up a good relationship, with me organizing a series of lunches and dinners at which he got to know leading politicians. He asked me what I knew about Edwina Currie and John Major and whether it was possible they had ever had a relationship. I was agog. He knew that, if true, it was an extraordinary story. But having spent most of his working life away from British politics, he was testing whether I saw it in the same light. My reaction told him. He asked me to read the diaries – but without telling a soul.

A manuscript arrived at my home by special delivery and I spent the next few nights racing through it, growing more and more stunned. I knew Major pretty well, and in the years before he soared to very high office he was someone with whom I often discussed the issues of the day. At this stage I was reading only the early entries in the diaries and Currie was writing intimately about her relationship with a man she called ‘B’. She called him B for no other reason than he was the second man in her life.

A typical entry was this: ‘Spoke to B this evening – I’m so glad he was in. Oddly enough I need the diary more now that he’s so busy. I wonder if it will start to fade. It’s so hard when I don’t see him. Still, I’ve thought that every year and we are still at it.’ The affair had started in 1984 and this was September 1987.

Another entry read: ‘I saw B again on Friday. I was in the area where he lives and his wife offered their home for a rest, which I appreciated. It’s nice, a bit plain and unimaginative. To my horror, the magic started to work again and in a very big way. When we parted he held my hand a long time and squeezed it, even though other people were there.’

Or this one: ‘Then B came along, and he was so bloody nice and attractive, and so quiet in public that it was a challenge to unearth the real person and to seduce him – easy! And it was unexpectedly spectacularly good for such a long time.’ This was not my normal terrain but I was riveted.

There were enough clues for me to realize quite quickly that B was indeed John Major. When I raced on to much later entries, after the affair ended in 1988 when B had become ‘John’, it was confirmed in my mind that, unless Currie had been victim to a lengthy fantasy, one of the most unlikely of political couplings had happened. I had to smile. Major was a Conservative whip when the affair started. The whips make it their business to know the private business of every one of their MPs, allegedly keeping notes in a black book. Here was one ex-whip who had kept a massive secret from his colleagues; even more surprising was that the affair was with one of the more colourful and controversial of their charges.

Brian MacArthur, our associate editor who was in charge of the whole operation and whose extensive publishing-world contacts helped us to get a first sighting of the diaries, had also read the extracts. I told Robert that it was clear it was Major. He asked me point-blank: ‘Do you believe it?’ I replied that I had to believe it, although if I had not seen the evidence I would not have done.

Next came a trip to the publishers Little, Brown on Waterloo Bridge, where MacArthur, George Brock (managing editor), myself, Ursula Mackenzie (the publisher), Alan Samson (the book’s editor), and our publicity chief, Mary Fulton, discussed issues such as where Currie would be over the crucial weekend after next and how I would approach Major. Our lawyer, Pat Burge, had warned from the outset that there might be two grounds for action of which we had to be aware – defamation if the story was wrong and breach of privacy. At that meeting the greatest worry was that Major might attempt to take out a privacy injunction when he learnt of what we intended to run. The general view was that I should leave the call to Major as late as I dared, to minimize that risk. But I stressed again the editor’s bottom-line demand: Major MUST be contacted.

Roy Greenslade, of The Guardian, wrote later that it was at a meeting in Wapping on 20 August that MacArthur and Thomson had first been told of the explosive, alleged contents of the diaries after signing confidentiality agreements. Both had agreed it was a great story, but asked if it could possibly be true. They were assured that it was. The publishers had come to The Times first because it was there that Currie hoped the book would be serialized.

As Friday, 27 September approached there was still in my mind, and in those of the handful who knew, that nagging doubt about what would happen when I got to Major with the news. Would he deny it, would he apply for an injunction, would he put out a press release telling the world in general and scuppering our exclusive? Knowing him, the latter was unlikely, but I was unsure on the other points.

No one in my office at Westminster was aware of what I had been doing. I went into the office very early that Friday morning and got the splash story written before anyone else appeared. I had during the week collected every possible number for Major – two office numbers in London, a Huntingdon constituency number, and several numbers for former close aides and friends. He was no longer in the Commons and my contact with him had been limited since the 1997 election defeat.

Peter Riddell – our chief political commentator – arrived back from the Lib Dem conference in the late morning. Peter was always my most trusted adviser and I confided in him about what we had got and showed him some of the relevant entries in the manuscript. If I was ever in danger of going over the top with a story, I could rely on Peter to pull me back from the brink, but this morning he said something I just did not want to hear. He wondered whether it was all an Edwina fantasy, the very doubt that had entered the head of Robert Thomson, me and others when we first learnt about it. At this stage I had not explained to Peter quite how much was at stake – the cost of the memoirs, the phoney first edition, the rest.

But I assured him I was satisfied and tried not to let any further doubts enter my head. The day went slowly by. At about 4 p.m. I was itching to call Major’s office number, but it was still too early. I would have some explaining to do if I called prematurely and an injunction swiftly followed.

At The Times the secret had been kept for thirty-eight days despite the number of people knowing about it gradually increasing, as the marketing director, picture editor, Ginny Dougary (who was to interview Currie in advance), and the night and design editors who were to work on the Currie edition, were all told. In the office the codename for the book among those who were in on it was ‘the Liverpool Novel’, after Currie’s birthplace.

Six p.m. arrived. OK. A deep breath. I had often in recent days framed in my mind how I would tell Major what we were about to publish. I rang the first number I had for the London office, which I had found in the past was always manned. No reply. I rang the second number. No reply. And no answerphone message on either. I had a mobile number for Arabella Warburton, Major’s chief of staff, too. No luck. It did not work.

This was worrying. I rang Huntingdon. Again no reply. Things were now serious. Not quite panic yet. But serious. I then, almost at random, started calling other people who might know where he was. I rang an ex-colleague, Sheila Gunn, who had gone on to work as a press adviser to Major. She did not know where he was and was very curious. I rang Jonathan (now Lord) Hill, his former political secretary. No joy. At Peter’s suggestion I rang Tristan Garel-Jones, a former minister and great friend of Major, on his number in Spain. No reply. In between all these calls I kept trying the London office numbers.

At head office everyone was busy preparing what they thought would be the paper’s main edition. Only the chosen few realized it was due to be just the first edition, so that rivals would not see the big one when it dropped in most newsrooms at around 10.30 p.m. It was agreed to put a story about Jeffrey Archer across the top of the front page. Full-page ads for the electrical firm Currys were put on pages four and five. Robert Thomson liked a joke. The staff were unaware that in another part of the building, a handful of their colleagues were preparing the real edition.

I told no one at the office at this stage that I was becoming desperate and that the whole thing was in danger of collapsing.

By now my deputy, Tom Baldwin, had arrived and I kept him in the dark, too – for the time being at least. But he could tell that his normally unflappable boss was anything but, and offered to help. Nobody could help, though; I needed someone, anyone, to answer one of these phones. I rang Huntingdon for the umpteenth time. London yet again. I tried Arabella’s number once more.

It was well after 7 p.m. when I tried the London office one last time, thinking that I was soon going to have to tell Robert that I could not find Major. Someone answered, apparently a secretary. I asked if Mr Major was there. No. I asked if Arabella was there. No. Aagh! I then told her that it was a matter of absolute life and death that I get hold of one of them. Was there anything she could do to help? She said she would try and I gave my Commons number. I repeated that it was of the utmost urgency and that they would be grateful to her if she could put them in touch with me. If I sounded desperate, I was.

No more than five minutes later, the phone rang. It was Arabella. I did not know how this conversation was going to go, but never had I been more relieved to receive a call. It sounded like a long-distance call and she told me she was in Chicago, where Major was about to make a speech. Yes, Chicago! I said that I must speak to him about something that The Times was about to run. I had to speak to him personally. She said: ‘You know, Phil, that you can tell me so that I can tell John.’ I said that on this one occasion it was difficult and that I really had to speak to him. Arabella could tell that I was serious and she must have wondered what on earth it was all about, given my insistence. She said that she would talk to Major. But I said: ‘Please don’t ring off – I don’t want to lose you at this stage.’ Arabella, who had always been the most straightforward person to deal with, was magnificent. She came back on the phone very quickly and said that whatever it was, however personal, I could tell her and that Major was happy that I should.

Tom Baldwin had been listening, and asked if he could get me a drink. I gave him the thumbs up and he raced off. I now had to tell Arabella what we were about to run. In my own mind I suppose I assumed that Major may have by now guessed what was coming. I did not know if he had picked up from somewhere that the Currie diaries were imminent. In any case I supposed this was something he had known might be revealed at any stage in the last thirteen years.

I told Arabella the essentials of the Times splash – that we were serializing Currie’s diaries and that she had disclosed that she and John Major had had a four-year affair. Arabella was clearly shocked but she was utterly professional. Her calm in the face of what I told her made me feel that there was unlikely to be a denial or any attempt to stop the story. The reaction was more one of sad resignation. I told her that if it was possible to have some response from her boss – and quick – I would be massively grateful. By now my anxiety had given way to huge relief. I had fulfilled Robert’s command.

And I now told him that the contact had been made, and that I was hopeful of getting some kind of comment from Major. It was by then close to 8.40 p.m. Arabella asked if I could give her twenty minutes and I said of course, but please come back to me even if there is nothing other than a ‘no comment’.

Tom Baldwin returned with beers and pizza. The Press Gallery bar was closed, it being a Friday. He had been up to Victoria Street. I was starving and thirsty. Again I told Robert that we were nearly there. Maybe twenty-five minutes later my phone rang again and I knew it would be Arabella. As I said hello, I quietly dialled Robert’s direct line in the office and heard him pick it up. She did indeed have a statement. And as she read it I repeated it out loud so that Robert could hear. It was 9.12 p.m. The statement read: ‘Norma has known of this matter for many years and has long forgiven me. It is the one event in my life of which I am most ashamed and I have long feared it would be made public. Neither Norma nor I has any further comment.’

Major has stayed true to that statement ever since. His first thought when he learnt of what we were running was for his family, and he obviously wanted to tell them what was appearing. But he has never since that day said another word on the subject.

I thanked Arabella. She in turn thanked me for giving Major advance knowledge and a chance to respond. It was a stunning result for the paper. Not only was the story confirmed by the main subject, he had also given a very good quote talking about his shame at what had happened. Even at that stage Tom and I surmised that Currie – hidden away in France – would not take too kindly to Major’s response. It gave us a follow-up for Monday morning.

My office sources tell me that it was at this stage that the editor of The Times gave out a whoop of delight and did his jig. I swiftly e-mailed Major’s words to the night editor, Liz Gerard.

The main paper of the night was then prepared at lightning speed.

As Brian MacArthur wrote later: ‘We had our scoop. Our rivals had the spoof. The new front page and pages four and five – carrying the Dougary interview – were ready to go immediately and were being printed by 9.36 p.m. Out of 655,000 copies printed from London, only 18,000 were the spoof edition. Luck plays as big a part in newspapers as in other areas of life and none of the nightmare scenarios we had considered occurred on the night.’

I didn’t tell them even then that for ninety minutes or so I had gone through a real nightmare. But I’ve mentioned since to George Brock, among others, that it nearly didn’t go all right on the night. George replied: ‘OK, there was the odd ripple of alarm. We knew you’d manage and you did.’

When the edition was done, a glass or two of champagne was drunk at the office – well deserved given the brilliance of the operation marshalled by Thomson, his deputy, Ben Preston, and the rest of the team. Tom and I had our beer.

I went home shattered but the tension of the night made sleep impossible. I was up early and in my car driving north to the Labour conference in Blackpool (via a Norwich match against Preston at Deepdale) when Robert Thomson was introduced on the Today programme by John Humphrys and interviewed about one of the great scoops of recent years. Piers Morgan, then editor of the Daily Mirror, who was woken after 2 a.m. when our Currie edition landed in his office, wrote that it rated as a story alongside ‘Elvis Dead’ and ‘Man on the Moon’.

A Day in the Desert as John Major Sues

My job was full of coincidences. Nine years earlier, I had been with John Major when he announced he was suing two magazines for libel for alleging – falsely – that he had an affair with Clare Latimer, a Downing Street caterer.

Stopping off in Oman – where he went off to the desert to see the sultan, on his way between Mumbai, India, and Riyadh, Saudi Arabia – Downing Street officials announced that he was taking legal action against the New Statesman & Society and Scallywag over the allegations about his private life. Clare Latimer also took action.

News that the New Statesman had repeated rumours that had appeared in the satirical magazine the previous month reached Major and his team very late the previous night in Bombay. It meant little sleep for him or the travelling press, who raced around for most of the early hours looking for comments, and in the paper of 29 January, I chronicled the events in Major’s extraordinary thirty-hour day.

All of us were up at around 5 a.m. on the Thursday, after at the most three hours of sleep. The decision to sue was taken on the plane to Muscat and announced by Gus O’Donnell, the PM’s press secretary, on arrival. Returning from the overpowering heat of the desert, Major staged a press conference and took the inevitable questions from UK reporters who were not too interested in the news of orders received from the Omani Government.

At 6 p.m. that night we put down in Riyadh, where Major had six hours of talks with King Fahd and other ministers. At midnight we were told that British Aerospace was to supply forty-eight Tornado aircraft to Saudi Arabia in what was Britain’s second-biggest defence contract. Both the libel and Tornado stories were spread across the front page of The Times. In the early hours of Friday we then got on the plane for Heathrow. A long day in our lives.

Fast-forward nine years and an angry and relieved Clare Latimer voiced her satisfaction that the ‘shabby truth’ had come out at last. She spoke of her pleasure that the real ‘other woman’ in Major’s life had identified herself, sparing herself the fate, as The Times reported, of becoming a footnote in the history of Conservative sleaze in the 1990s. ‘The world will now hopefully believe I did not hop into bed with John Major,’ she said.

There were other spin-offs from our sensational revelation that Saturday. As Tom Baldwin and I had predicted, Currie was not best pleased. From her hideaway she spoke of the hurt she felt at his describing his shame over the affair. ‘He was not very ashamed of it at the time I can tell you. I think I’m slightly indignant about that remark.’

And for the Kremlinologists of Westminster – those of us who enjoyed analysing every word and gesture from politicians to divine their motives and feelings – it threw some light on Major’s decisions not to bring back Currie to the Government from which she had resigned as health minister in 1988 over remarks about salmonella in eggs.

In her diaries she claimed Major had told her shortly before he became prime minister in 1990 that she might become housing minister in the reshuffle that followed his win. But no offer came.

Then, after Major’s victory in 1992, we watched on reshuffle day as Currie marched happily up Downing Street. We expected her to get a Cabinet job but Major offered her the post of prisons minister under Kenneth Clarke, the home secretary. But their relations were not good when Clarke was her boss at health and she refused, and walked down Downing Street, this time less happily.

In 1991 she had written in the diaries: ‘He did not keep his promise to me … that hurt so terribly. I think I’d like the man to know exactly what he did last winter and how I felt, preferably not when the knowledge can do any damage, but he won’t always be prime minister and it won’t always matter.’

It was, indeed, a prophetic entry, and it was another eleven years before she did the deed.