Читать книгу Inside Story: Politics, Intrigue and Treachery from Thatcher to Brexit - Philip Webster, Philip Webster - Страница 7

Introduction

ОглавлениеLife is full of chances. A chance visit to The Times’s office at Westminster on a Tuesday in July 1972 led me to an adventure lasting more than four decades which finally ended in January 2015, after my 15,932nd day as an employee of the world’s greatest newspaper. I am lucky to have been part of a small chunk of its 230-year history.

In those days The Times had far more reporters in Parliament than any other paper and gave far more column inches to coverage of parliamentary affairs. Unlike many other papers, it had its own office, known as The Times Room. I walked into The Times Room on that July afternoon during a tour round the House of Commons. I was a subeditor on the Eastern Evening News in Norfolk, and Tuesdays happened to be my day off. I had been to the office of the Commons Official Report, known as Hansard, next door and the editor kindly took me to meet the head of The Times’s parliamentary staff, Alan Wood. It being a Tuesday, Prime Minister’s Questions were about to happen. In those days it was two fifteen-minute sessions on Tuesday and Thursday. Alan gave me a notebook and took me into the gallery, asking me to have a go at recording the exchanges between Edward Heath and Harold Wilson. I had good shorthand, which Alan could see, but my efforts at reading it back were patchy to say the least. In any case there were no jobs going.

Four months later I received a handwritten letter from Alan telling me a vacancy had arisen and asking if I would be interested. I went down to the Commons again in mid-January. It was again on a Tuesday and my left arm was in a sling after a football injury that Saturday. The cynics in the office smiled to themselves, thinking I had come up with the ultimate alibi for a failed test in the gallery. Fortunately, I’m right-handed.

Alan Wood put me through the same process and, this time, knowing what to expect, I made a good fist of it. He asked me to head down to Printing House Square at Blackfriars, then the home of The Times, where I was interviewed by John Grant, the managing editor. He was at the time president of the National Council for the Training of Journalists (NCTJ) and it helped a lot that I had been on one of the NCTJ’s pioneering full-year courses, and had secured the NCTJ diploma at the end of my training period. He offered me a job and I bit his hand off. It was the biggest decision of my life but it was not at all difficult.

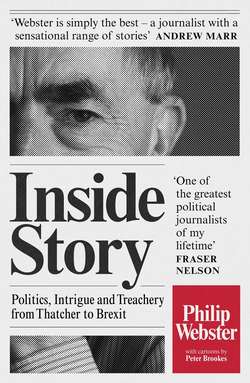

Forty-three years later I have written this account of my career covering politics for The Times. It does not pretend to be a political history of the period. Enough biographies and autobiographies have been written to do that job many times over. But I have found myself at the centre of most of the big stories of the last thirty-five years – the fall of Labour in 1979, the rise and fall of Margaret Thatcher, the emergence and fall of John Major, the rise and fall of Tony Blair and his wars with Gordon Brown, the aftermath of 9/11, the war in Iraq, the fall of Brown, the rise and rise of David Cameron, and the shock election of Jeremy Corbyn. This is my take on some of the big things that happened, and how I covered and unearthed them.

Being a political correspondent of The Times, including eighteen years as its political editor, has given me a ringside seat at the most dramatic political events of the last quarter of the twentieth century and the early years of the twenty-first. Although my predecessors have probably felt the same – and despite having no illusions myself – this to me has seemed like a golden era of political journalism and I am lucky to have been part of it. During all those years I was a member of the Westminster Lobby, whose merits or otherwise I deal with later.

It was a position that gave me ready access to politicians of all parties and I got to know them well, including four prime ministers, any number of Cabinet ministers and countless back-benchers, as well as the hundreds of officials and advisers who support the ministers and their shadow ministers in their jobs.

It was a role that gave me the opportunity to travel the world – a rough calculation puts my total air miles in the service of The Times at close to the million mark – as well as a seat in the Commons Press Gallery at every significant event. I was there the night Michael Heseltine brandished the mace, the night the Callaghan government fell, the day Sir Geoffrey Howe brought down Margaret Thatcher, the days she and Tony Blair said farewell, the night MPs voted for war in Iraq, and for every Budget and autumn statement for forty years.

Occasionally it was a role that landed me in the most unexpected, even dangerous, scrapes. But most of it was fun, and if the reader does not get the impression after reading this that I had a very good time I have failed in my task.

It was also a position of huge responsibility, something of which I was well aware and about which I sometimes worried. The political press clearly has an important role in holding politicians to account. But what we write shapes events and makes or breaks careers, including those of party leaders. A few reporters have gone on to work for political parties but the vast majority are not players. Most political correspondents have no allegiance to a party. I never have or will but I have good friends in all the parties. The reader may find this strange, but in the tens of thousands of conversations I had with politicians while I was a senior political correspondent, not one asked me how I voted. I imagine they felt that as an impartial reporter I would have been insulted by the question, but I would have had an answer: I did not vote during those years.

Political correspondents are without doubt an integral part of the political process. It places a severe duty on us to get our stories right, ensuring they are fair, accurate and impartial – the mantra that is drummed into us from our first day in journalism school. When I appeared before the Leveson Inquiry into press standards in 2012, one point I tried to make very firmly was the importance of separating fact and comment in newspaper coverage, a line that has occasionally been blurred in recent years.

What I have tried to do here, having written about all these events as they happened, is to offer a fresh insight on them and reveal, as far as I can without compromising living sources, how stories I wrote at the time came into my hands and influenced events as they unfolded. Sometimes the stories originated from me learning from one source or another that something was brewing, and then nagging the people in a position to know until I was able to write. Sometimes, particularly when the parties started pre-briefing announcements rather than waiting for them to be put to MPs in the Commons – a practice that has infuriated successive speakers – they have come to me without a struggle. There was a time in the early years of New Labour, in government and opposition, when I would be surprised if there was NOT a phone call from Alastair Campbell or his Conservative counterpart when I came off the golf course on a Sunday lunchtime, on what until then had been a day off. On those occasions I would often spend the next few hours in my car, making calls to the office and contacts.

It could be a risky business. In the pages that follow I tell of many occasions when I pushed a story to the limits and spent worrying hours wondering if I would be embarrassed when it appeared.

Britain had eight prime ministers during my years as a reporter at The Times. I worked under nine editors, starting with William Rees-Mogg and finishing under John Witherow. Labour was on its way to power, or in power, for most of my eighteen years as political editor and for obvious reasons those years are covered comprehensively in what follows. I was fortunate that in my time as a junior Lobby man I was assigned the Labour beat when it was in opposition, meaning that I got to know well the men and women, and their aides, who were to become the leading figures in the party as Blair pushed for power, and he and Gordon Brown held sway for thirteen years.

I left Westminster in 2010 and after a four-year period as editor of The Times digital editions, I grabbed John’s offer to become assistant editor (politics) of The Times and to be the first editor of the ‘Red Box’ daily political bulletin and website. It meant I was back reporting on politics in time for the 2014 Scottish referendum and the 2015 general election. I had never been far away, though, and had continued to write about politics in the interim period, so this was another chance in a life of chances that I was not going to pass up.

As I’ve looked through mounds of my cuttings while writing this book, I’ve been struck by just how much I did. I only kept sparse notes of key conversations and cuttings of which I was particularly proud. I have a strong – my friends say nerdish – memory for the minutiae of the major political events in which I was involved, but in my trawl of the files I have come across stories under my byline and trips to the other side of the world which had temporarily gone from the memory.

Political journalism has changed in my years, as I explain later. Television has taken over from the House of Commons as the cockpit of political debate. Power has shifted from Westminster to the television studios, to Europe and to Scotland. But my successors need have no fear. There will always be a need for journalists to work and watch closely as politicians exercise their power.

My story is of one journalist who stuck with the same paper, the one he had always dreamt of working on, and resisted the occasional blandishments of rival editors who told him his career would progress faster if he moved over to them.

This book is about the story behind the stories that ran across the front pages of The Times for four and more decades. There were serious, tragic, sad, dramatic and traumatic moments behind those stories. But chasing them and writing them was a great joy and privilege.

I start with the momentous events of 23 June 2016 that changed all our lives, finished off another prime minister, split the country in two and left British politics in utter turmoil.