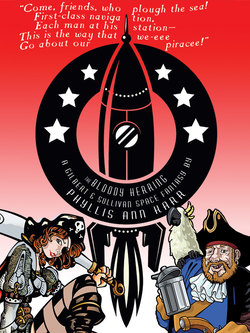

Читать книгу The Bloody Herring - Phyllis Ann Karr - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 3

The Map

In a bookshelf-lined chamber deep within the castle, a young man in Regency attire picked up a dagger with an ornate Florentine handle and a blade of Spanish steel gleaming blue in the firelight. Feeling through the cloth of his waistcoat, he placed the dagger’s well-sharpened point in the furrow between the two ribs he judged most immediately over his heart. He then leaned back in his armchair, waiting for the courage to drive home.

After a few minutes, with a sigh and a shudder, he lifted the dagger away, tossed it on the small table beside his chair, and rubbed one fingertip over the frayed threads in his waistcoat. Someone, he sensed, might be coming—someone who could possibly help. He took another drink from his goblet and picked up his book once more.

* * * *

Chuck found a footpath of sorts on the other side of the sheep pasture, but already it was a channel of mud, and he kept as much as possible to the slippery grass and weeds beside it. The trail led straight through the small graveyard. He wondered whether relevant clues might be found on the tombstones, but those nearest the path were lichened over, the inscriptions all but obliterated; and he did not stop to investigate the monuments farther away. The castle should be at least equally fruitful in clues, as well as drier.

There was neither moat nor drawbridge. He mounted about a dozen cracked stone steps to a Gothic arch, and found the massive oak door standing two feet ajar. Was someone trying to draw him inside? Drenched as he was, before entering he lifted the heavy iron knocker and let it fall several times. Its echoes gave the impression of long hallways and empty chambers. The knocker was shaped like a herring, and when he took his hand from it, his fingers were smeared with a brownish-red stain, like rust or dried blood.

He rinsed the stain off by rubbing his hands in the falling rain. Then, no one having answered his knock, he pushed open the door, stepped inside, and pushed it almost shut again, listening to its squeaks and being careful to leave it ajar as he had found it. Stumbling on a loose piece of masonry in the hall, he moved the chunk into place to prevent the door from closing all the way.

With little light seeping in from the murky day, and no kindled lamps on the walls, it might as well have been night in the vestibule. He dug his virtual flashlight from his virtual backpack, glad of the waterproofed canvas that kept the pack’s inside safe from the virtual rain. Virtuality could be very realistic. Aiming the beam of light around the vestibule, he located and lit a number of candles in wall sconces.

The walls were covered with medium-large pictures in gilt frames. He examined them by the light of the candles, using his flashlight whenever he wanted a closer look at some detail. The pictures were theatrical costume designs, unexpectedly airy and colorful in this gloomy hall.

He looked over several costumed figures—English village girls, Peers of the Realm, fairy-tale princes and princesses, gaudily melodramatic pirate captain, quaintly old-fashioned London bobby, Japanese costumes with exaggerated fans on suspiciously non-Oriental-looking people, a pair of gondoliers posed in imitation of Siamese twins, a vaguely Wagnerian fairy queen…all Gilbert and Sullivan characters. Of course.

And here was the picture of a thin, sallow-faced fellow in velvet knee breeches, his hair wildly bouffant and an oversized lily in one hand. Bunthorne, from the operetta Patience. Steve Davis had played that part in Antique Terra’s repertory the first couple of years after Liftaway and again in the revival two years ago. When Lozinski also had tried for the part.

This time around, in Antique Terra’s Yeomen of the Guard, Lozinski had the part he’d wanted. The part both he and Davis had wanted. The late Steve Davis, who—according to Deuteronomy Osborne, had had bigger things on his mind. Had Bob Lozinski?

Just as Chuck headed for the archway leading to the rest of the castle, he saw a picture of the woman he had met in the sheep pasture. Yes, there was no doubt: the same ragged garments, the same tangle of red-brown hair, the same piquant face with its abstracted yet curiously alert eyes. But which operetta did she come from? Dr. Falcon couldn’t quite remember. One Antique Terra hadn’t done yet?

He entered a long hallway, came to its end, found another, climbed up a flight of stairs, emerged in yet another hallway. Ever keeping a mental map of the way he had come, he followed the same procedure in each hallway—turn off the flashlight and try to spot a line of light seeping out from underneath one of the doors. At last, in the fourth passageway, along the bottom crack of the sixth door, he found such a line. Softly he turned the large gilt doorknob and went in, to find himself in a library, surrounded by the oiled spines of leather-bound books which gleamed in the light of candles and fire.

In a cushioned, highbacked armchair near the stone fireplace sat a smallish, black-haired young man in knee-breeches and a cutaway, swallowtail coat.

Glancing up at Chuck Falcon, the youth gave an exclamation of pleasure, closed his book and put it down between a half-drunk goblet of milk and a fancy dagger on a small table. Then he rose to greet his unexpected visitor. “Your servant, sir! Delighted to make your acquaintance! Mother of pearl, man, you’re drenched! Beastly weather in these parts—come over to the fire and dry yourself.”

He poked it up with a fire-iron and threw another log on the blaze. Chuck needed no further urging. The worst of the excess rainwater had dripped off in the passageways, but the warmth of the fire was still gratifying. He slung off his backpack and turned first his face, then his back, to the flickering heat.

His host straightened, looked at him, and hesitated a moment, still holding the poker uncertainly in his hand. Then, thrusting it back into its stand beside the fireplace, he went on, “Sherry? No—no, I think brandy, to take off the chill.”

“Brandy will be fine, thanks.” Studying the young man’s face, pale and haggard-eyed as it was, Chuck wondered if he had found Bob Lozinski.

* * * *

While his host was pouring the brandy, Chuck Falcon picked up the book the young man had been reading. It was a collection of poems by Swinburne and Morris, with a calling card inserted as a bookmark. The card was printed with the name “Sir Despard Murgatroyd, Baronet,” but the “Despard” was lined through and the name “Ruthven” printed neatly above it. In small Gothic letters beneath the name was printed, “Villain-at-Large. Abductions, Burglaries, Assassinations, & Other Assorted Criminal Activities.” In the lower right-hand corner was the simple address, “Ruddigore Castle.” Yes, all this sounded like Gilbert and Sullivan’s way of looking at things. But which operetta?

Chuck’s host turned with a snifter of brandy in each hand, and saw him reading the card. Noticing a slight blush spread through the young man’s cheeks, Chuck replaced the card, having kept his finger between the pages where he’d found it, and laid the book back on the table. “Sir Ruthven?” he asked conversationally, accepting his snifter.

“Rivven,” replied the baronet, correcting his pronunciation. “We usually utter it with the elision. Not a pleasant name in any case, is it? But I regret our lack of a formal introduction…”

“Falcon. Dr. Charles Falcon—call me ‘Chuck.’ I’m a stranger to these parts.”

“Dr. Falcon.” Sir Ruthven bowed, then lifted his own snifter of brandy. “Your servant, sir. To a mutually profitable acquaintanceship.”

Apparently, going by the half-emptied goblet of milk, Sir Ruthven was a social rather than a serious drinker. Now, after one (admittedly generous) swallow of brandy, he seemed to relax a little. “May I inquire, Doctor Falcon, what induces you to seek our peculiarly grim corner of the country?”

Well, why not start with something obvious? “I’m hoping to look up a fellow named Bunthorne.”

“Bunthorne? Not Reginald Bunthorne, the fleshly poet?”

Remembering the skinny character in the costume design, Chuck smiled. “Well, I’d hardly have called him ‘fleshly,’ but I believe he is a poet.”

“It refers to his style. Wait, I have his book here somewhere.”

While Sir Ruthven was searching the crowded bookshelves, Chuck took the opportunity to re-examine the volume his host had been reading. Opening it to the place marked, he noticed in the margin of the right-hand page a small, elegant pointing hand drawn in ink. He followed the pointing finger and read the lines:

“From too much love of living,

From hope and fear set free,

We thank with brief thanksgiving

Whatever gods may be

That no life lives for ever;

That dead men rise up never;

That even the weariest river

Winds somewhere safe to sea.”

“Ah, here it is!” came Sir Ruthven’s voice. Again Chuck replaced the volume of Swinburne and Morris on the table, as the baronet brought a slim leather-backed book to the fireplace. “Heart-Foam and Other Poems. Actually, he did not publish the title poem; but he inscribed it in holograph on the flyleaf of each and every copy:

“Oh, to be wafted away

From this black Aceldama of sorrow,

Where the dust of an earthy to-day

Is the earth of a dusty to-morrow!”

Sir Ruthven’s taste in poetry—assuming Sir Ruthven was Bob Lozinski—disturbed Dr. Falcon. But all he said for the time being was, “Very nice.”

“You really think so? Well, but you’re in the wrong part of the country entirely to find Mr. Bunthorne. He resides in Suffolk.”

“I see. Maybe you could show me a map?”

“A map? Nothing easier!” Crossing the library to an oakwood writing-desk, Sir Ruthven lowered its top and rummaged through the pigeonholes until he found a rolled piece of paper. Unrolling it on the desk, he weighted down one edge with a blown-glass paperweight, looked around for something to hold down the other edge, and chose the heavy-handled Florentine dagger that had been resting on the table with his book and milk.

Chuck squinted down at the map, memorizing it. As nearly as he could remember from Chandra’s schooling, both the early part of it back on Old Earth and the advanced degrees earned in Papa’s Pride, it showed a fairly accurate representation of southern England, with Penzance, Portsmouth, and London clearly marked about where he thought they should be. But the size of southern England seemed to be exaggerated, and the size of the surrounding bodies of water and land shrunk, so that in the heart of a scaled-down eastern Europe Chuck quickly saw a bright gold area labeled “Pfenning Halbpfennig” in large letters, and above it to the northwest a tiny drawing of a fortress labeled “Castle Adamant.” More operettas he wasn’t familiar with. At the top of a miniaturized Italy he found Venice; and just off the coast of a squashed Spain he noticed an island named Barataria—that was for The Gondoliers, which Chandra had seen. Beyond Barataria was another island, named Utopia—that rang no bell—and beyond that, with no regard for the American continents or the Pacific Ocean, was Japan, its principal metropolis captioned Titipu.

“Here is Ruddigore Castle, where I regret to say we are now.” Sir Ruthven pointed to an ill-starred location near the western tip of Cornwall. “And here,” he went on, moving his finger across the map past London to a site near the eastern coast, “is Castle Bunthorne.” Returning his finger to Ruddigore Castle, he traced a line along the southern Cornish coast. “Now, I think your best plan would be to travel overland to Penzance. If you tell the Pirates you’re an orphan, they’ll gladly smuggle you to Portsmouth. From there you can probably find passage on the Pinafore to Ploverleigh, here—and one of the villagers will be honored to drive you the ten miles further inland to Castle Bunthorne.”

“Thanks. This is a great help.” Though Chuck preferred to stick near Sir Ruthven. Considering that the secondary sharer of this kind of virtual world ought to meet the primary sharer quite early, if the madwoman hadn’t been Lozinski, it logically almost had to be the baronet. “Of course, I don’t much feel like starting out in a storm.”

“That’s understood.” Sir Ruthven lifted the dagger from the map’s edge and shifted his fingers nervously from handle to blade and back. “You’ll dine with me, of course, and—stay the night. I’ll…I’ll ring for my man to air out a room for you.”

The baronet started toward the bell-pull, and Chuck bent over the map again, holding its unweighted edge down with his hand.

The next instant he felt a sharp point at his back.

“I…apologize for this with all my heart,” said Sir Ruthven. “I assure you, I bear you no personal ill-will whatsoever. Quite the contrary. But…”

* * * *

Chuck was not alarmed for himself; nor, with his assorted black belts, was his attacker in any particular danger. Suddenly ducking forward, he threw his left elbow around in a back hook that connected with the baronet’s hand and sent the dagger clattering across the floor. Continuing the movement, he straightened his arm, caught Sir Ruthven’s forearm near the wrist, and spun his own body around to face the pale and shaken baronet.

Sir Ruthven dropped to his knees and buried his face in his free hand. Chuck released his other arm and said in a firm but quiet voice, “All right, now suppose you tell me why you tried it.”

“I’m…awfully glad you did that.” Pulling himself together Sir Ruthven got to his feet again. “It was expected of me—I think you read my card?—but you can hardly imagine how grateful I am to be foiled. I trust this won’t prevent you from stopping to dine with me?”

“Leaving now would be the farthest thing from my mind.” Chuck returned to the fireplace, pulled up a second armchair, and sat. The baronet followed his lead, sinking again into his own faded plush chair. Chuck warily relaxed.

“I expect you’ll want a room with a lock?” asked Sir Ruthven.

“No.” Chuck saw that his host would doubtless have his own complete set of keys. “I’ll want a room with an inside bolt and some heavy furniture I can move against the door.”

“An excellent precaution. I congratulate you heartily and will see to it that your wishes are fulfilled.”

Both sat silent for a few moments, the baronet staring into the fire, Chuck sneaking glances at his haunted profile. After a short time Sir Ruthven said diffidently, “You know, I…I’m a rather better poet than Mr. Bunthorne, myself.”

“Oh?” Chuck tapped his fingers together meditatively. “I’d like to hear your stuff.”

“It’s all in manuscript, of course. I haven’t published.” The baronet rose and pulled a bound notebook from the shelves. After some self-conscious riffling through the pages, he nodded and began to read, wandering around the room as he did so:

“Oh, painful is the honeybee’s mistake,

Who stings the careless hand that meant no harm.

And painful is the martyr’s fiery stake,

Who senses, at the climax, some alarm.

And painful is the lobster’s bubbling lake,

Who’s dropped in by the cook’s relentless arm.

But to their endings let us now cry truce—

These creatures did not live without some use.”

Sir Ruthven had wandered behind his guest’s chair during the last few lines, his footfalls ceasing as he reached the final couplet. Now, when his voice also stopped, Chuck felt a surge of alarm.

Jumping up, he turned and saw the baronet huddled on the floor, his book still in one hand, his other hand closing around the Florentine dagger, which Chuck had neglected to retrieve from where it had fallen. Without a glance at the other man, whom he apparently believed still watching the fire, Sir Ruthven turned the blade toward his own chest.

Chuck pushed over his chair. As Sir Ruthven turned at the crash, Chuck sprang upon him and wrestled away the dagger. This time he carried it to the fireplace and dropped it deliberately into the flames. For a while, at least, it would be too hot for any more mischief.

Sir Ruthven was definitely suicidal, as Chuck had already feared from his taste in poetry. And he might be more dangerous as a would-be suicide than as a would-be murderer.

If he was Lozinski, and succeeded in killing himself, what would happen to whatever he knew about…whatever Deuteronomy Osborne suspected was about to “go down”?

That his whole virtual-reality world would vanish went without saying.