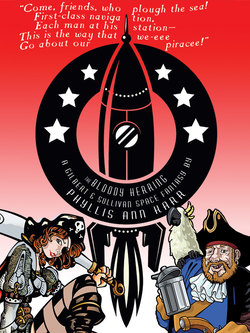

Читать книгу The Bloody Herring - Phyllis Ann Karr - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 5

Encounter on the Cliffs

Chuck took care not only of cooking the meal, but also of laying the table in the dining-room immediately upstairs and of selecting the wine—a bottle labeled “Pommery ‘74.” By now he had decided that his host’s earlier statement about a servant on the premises had been a mere pretext to make the half-hearted attempt on his life. Either that, or Lozinski had somehow quietly written the servant out of the virtual script.

On being released for the meal, Sir Ruthven seemed deeply moved to find himself trusted with a table knife. “True,” he observed, “it is far from sharp, but, for all that, a sudden lunge at the face—”

“Would probably do less damage with a table knife than with a fork,” Chuck replied. “And I’m not going to make you eat with your fingers.”

He abandoned his earlier design of sleeping in a room with an inside bolt. He had no intention of leaving his host alone to make another suicide attempt. To help ensure them both a good night’s rest, he mixed a harmless sleeping compound from the virtual medkit in his knapsack into the baronet’s after-dinner brandy. “How very clever of you!” was Sir Ruthven’s comment on learning he had just been drugged. “Not quite necessary…I rarely make the attempt at night…the more unpleasant aspects of the next life look a little too strong by night. Still, deuced clever of you…” Then the drug took effect.

After carrying his host upstairs and finding a suitable bedroom, Chuck left him long enough for a brief trip back to the library. A quick check of the reasonably well arranged shelves did nothing to disprove the theory of the Gilbert and Sullivan libretti being unavailable as such in a virtual scenario based on them. Good thing he had that virtual copy in his knapsack. Reasoning that sitting Sir Ruthven down with a ponderous tome which required at least two hands to manage, and instructing him to read aloud, would keep him out of mischief while Chuck fixed breakfast in the morning—any cessation in the reading voice would alert him to trouble at once—he selected more or less at random what looked by title to be the least weighty—in subject matter, at least—of the large leatherbound folios.

Next morning, Sir Ruthven agreed that the idea was excellent in principle, but could not suppress a smile at Chuck’s choice of folios. “The Merrie Jestes of Hugh Ambrose—I fear we shall both regret this, doctor!”

He was right. Long before the bacon and eggs were ready, Chuck had resolved that next time he would stick to light and frolicsome reading matter, like the Roman Martyrology.

Despite Hugh Ambrose and his Merrie Jestes, the baronet seemed in a comparatively cheerful mood. “I have decided to misdirect you today,” he informed Chuck happily. “So if you hope to reach Penzance, you’ll do best to ignore what I tell you and ask your way of the virtuous countryfolk instead.”

“Thanks for the warning, but you’re going with me.”

Having just taken a bite of toast, Sir Ruthven swallowed it before replying. “You honor me, but if you expect me to prove a trustworthy guide—”

“Not at all. I’ll still ask the way of your virtuous countryfolk. But you’re still coming with me.”

“Do you presume to order me about in my own ancestral hall, sir?”

“Yes.”

The baronet’s sudden show of wrath subsided as quickly as it had appeared. “I do it on compulsion. Well, it seems a fine day for an outing, and I daresay it’ll do me good to get away from the gloomy old pile for a while.” Helping himself to more eggs and bacon, as if to fortify himself for the day’s exercise, he went on, “You’ll want me to accompany you all the way to Penzance, I take it?”

“All the way to Castle Bunthorne, if necessary.”

Sir Ruthven looked at him in surprise, then calmly spread marmalade on another piece of toast. “You’ll probably regret it,” he said, in a voice that implied, “But I won’t.”

* * * *

“Fortunate weather for traveling,” Sir Ruthven remarked an hour later, as they strode along on the pleasantly springy turf beside muddy footpaths, with a cloudless sky arching above. “And so you still believe me to be this Lozinski, and feel compelled to prevent my destroying the entire world along with my own expendable existence?”

“Well, actually,” Chuck found himself admitting, “I’m only about eighty-seven percent sure. Keep concentrating on good weather, and maybe we can test it out.”

“Whereas if I am not he, then I am merely a fragment of his imagination, whoever he is. Hardly flattering, that. The surest test for you, of course, would be to give me a compassionate push over the nearest cliff.”

“No.”

“Well, Dr. Falcon, I don’t know whether you’re mad or merely a merry wag, but it should prove diverting to help you search for the mind who, by your theory, controls…” His voice trailed off. They had just rounded a turn in the path, and in front of them, balanced full-length on her stomach, atop a long boulder, was the same young woman Chuck had encountered yesterday in the sheep pasture.

“Meg!” whispered the baronet.

“Oh, the brave bold poppies! See! See them fly away on their wings, all red and gossamer with their great black and gold lips dripping sweet, sweet power?” Half rising on one arm, she pointed past the men into the distance, energetic for an instant and then suddenly languorous again.

“Meg!” said the baronet once more, advancing a step.

“Meg—beg. Keg—leg. Beg—badge—Madge. Daft Madge!” As if she had settled the matter to her own satisfaction, she chuckled and slid more snugly in among the rocks, wagging an admonishing finger at him. “Daft Madge—Poor Peg. What things are you, so brown and blue?”

Dr. Falcon wondered what she was seeing when she looked at them with those wide, green, glazing eyes.

“Margaret!” The baronet was halfway to her perch in the boulders overlooking the sea. Dr. Falcon stayed uninvolved and in the background, studying the scene as dispassionately as possible.

Sir Ruthven came a few steps closer to the woman, holding out his arms beseechingly. “Margaret—don’t you know me?”

She stared down at him. Her eyes seemed almost to focus. Then suddenly she sprang to her feet on the boulders. “Don’t come! Don’t come!”

He stopped dead in his tracks, but kept on talking, persuading. “Come down, then. I won’t hurt you, Meg. You know I won’t hurt you. Come down!”

“Hush! Don’t you hear it? Oh, the bright purple wind in the waves, in the waves…” She began to sway back and forth, perilously poised on the rocks above the sea.

“Margaret, be careful! Meg, Meg, come down!”

She looked at him again. “Don’t come any nearer. There’s blood beneath your fingernails.” Smiling mischievously, she lifted one bare foot from the rock and began to sway again.

Sir Ruthven dashed forward, clearly hoping to catch her before she fell. She watched him for a few steps, chuckled, and delicately stepped off the boulder into space and disappeared from their sight.

“Margaret!” screamed the baronet, falling to his knees and burying his face in his hands.

Chuck sprang forward at last, hardly sure whether he or the baronet were the more alarmed. If he had been wrong—if Margaret were Lozinski… Chuck clambered up the boulders and looked over the cliff’s edge, half-expecting that at any second Lozinski’s virtual world and everything in it might collapse around him. And if that happened…was Chandra Falcon’s own mental health quite safe?

He let out a sigh of relief. A wide ledge ran along the face of the cliff wall, slanting down gradually to join the beach. Margaret had landed safely, about eight feet below Chuck’s vantage point, and was skipping down to the sands.

Chuck turned back to the baronet, who knelt weeping in the grass. “She’s safe. There’s a ledge.”

“Thank God!”

“Hmmm.” Chuck rubbed his chin, noticing that here in virtual reality, Chandra’s inner man was growing beard stubble. Should’ve remembered to use the virtual, battery-powered razor in his knapsack this morning. “You’re a native of these parts?”

Still kneeling, Sir Ruthven nodded.

“And you didn’t remember that ledge was there?”

“What are you hinting at, doctor?”

“Only that whoever is building this world in his mind—genders can fluctuate ‘in here,’ but ‘out there’ we know it’s a ‘him’—could have put a ledge right where it was needed at an instant’s notice.”

“Please, Dr. Falcon. Is this a time for jesting?” Sir Ruthven eyed his fingernails wearily. “I have never felt less like a god than at this moment.

“Egocentric again.”

“Sir?” The younger man looked up in pained aggrievement, but Dr. Falcon, having decided it was time for the emotional equivalent of a slap across the face, went on,

“You assumed I was talking about you. I could as easily have meant her. “

“I stand corrected.” As if to suit the action to the words, Sir Ruthven rose and dusted off his knees. “But I fear,” he added, shaking his head, “that if this world were a creation of poor Margaret’s brain, it would have even less of sense and justice than it has.”

He turned and began walking along a path that cut inland, between the fields. Chuck caught up with him in a few long strides and then moderated his pace, his own brain working the while.

He knew, now, where these two characters came from. It had been easy enough to check last night in his virtual copy of the librettos, simply by scanning the cast lists. And there really was very little connection, in their own operetta, between Sir Ruthven and Mad Margaret.

There was obviously a connection in Bob Lozinski’s virtual fantasy.