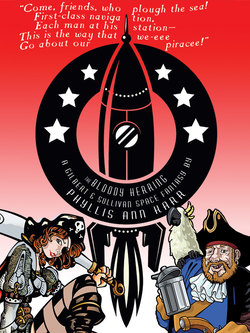

Читать книгу The Bloody Herring - Phyllis Ann Karr - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 4

Philosophy in the Kitchen

“All right,” said Dr. Charles Falcon, “now suppose you tell me why you tried to do it.”

“I should have thought my reasons not only obvious, but laudable.” For the second time, Sir Ruthven gathered himself up from the floor and returned across the room to drop into his armchair. “I quite appreciate your motivations for foiling my attempt on your life, but I’m dashed if I can see why you foiled my attempt on my own!”

“Let’s just say you promised me dinner.”

“True. There is that.” Nodding as if that settled the whole question, Sir Ruthven drained off the rest of his milk like an old imbiber. “But I have been remiss in my duties as host. No doubt you wish to dine as soon as possible.” He stood up briskly and started for the door. “I’m not entirely sure what the larder affords today, but I believe there’s half a joint, or a promising leg of mutton if you’d prefer—”

“I’d prefer,” said Chuck, noticing that his host had said nothing more about having a servant on hand, “to do the cooking myself.”

Sir Ruthven stopped and looked back at him, momentarily puzzled. Then his face cleared. “Ah! Do you expect me to poison you, or myself, or both?” Picking up a lighted candle, he opened the door. “Allow me to show you to the kitchen, then. I’m quite safe for the moment.” He playfully lofted the candlestick an inch or two. “I really have no desire to set either of us aflame.”

Chuck blew out the candles in the room, hefted his backpack, and followed the baronet out of the library, through numerous corridors, and down numerous stairways, continuing to keep a mental map of the building. If its floorplan did any changing, he wanted to know.

Four corridors and five stairways later, having reached the level below the door through which Chuck had entered the castle, they arrived in the kitchen, a cavernous, high-beamed vault complete with banked fire in huge fireplace, stone oven, festoons of onions and sausages (but no garlic in sight—Dr. Falcon thought she remembered from a lit class somewhere that Polidori’s “Lord Ruthven” had been the popular Victorian vampire before Bram Stoker’s Dracula), larder, buttery, salt closet, and—the one false note in an otherwise convincing layout—a sideroom which Sir Ruthven referred to as a “galley” and which apparently existed here only because Bob Lozinski had a vague idea that a galley should be here, without knowing exactly what it was.

“Assuming you will find my company de trop, I’ll leave you now, to await the outcome of your culinary endeavors.” Sir Ruthven began to bow himself out, but Chuck stopped him.

“You’re assuming too much, my friend.”

The younger man blinked. “You prefer to chance having me here to slip nightshade or belladonna into the soup when you’re not looking?”

“Better that then have you trying to do away with yourself again once you’re out of my sight.”

Setting his candlestick down on a table, the baronet quietly opened a drawer and brought out a coil of thick satin cord, the kind used for old-fashioned bell pulls and drapery ties. “Best bind me,” he said pleasantly, handing it to his guest. “I’ve forgot where I last hid the belladonna, but there’s any number of cleavers and such about the place.”

Chuck decided to adopt the suggestion. It would put them both more at their ease, mentally at least. “Rather odd gear for a kitchen,” he remarked, accepting the strong but luxurious cord.

“One never knows where and when one may need a length of rope in this beastly castle. I find it best to guard against such emergencies as the present.” Sir Ruthven settled down in a heavy, high-backed wooden chair and held out his crossed wrists. “I had a namesake once who contrived to behead himself,” he went on cheerfully. “Made a very neat job of it, too.”

“Must have been quite a trick. Hardly the kind of thing anyone can practice ahead of time.”

“Even if one could succeed in cutting it only half off, that would be something.”

Dr. Falcon had only a first degree black belt in hojojutsu—the ancient martial art of binding an attacker or prisoner securely, artistically, and non-injuriously—but the cord seemed more frictive than satin might prove in actual reality, and Sir Ruthven both cooperated and watched with what resembled professional interest, even expressing the hope that someday, when it was quite convenient for them both, Dr. Falcon might give him a formal lesson or two.

The baronet secured artistically, non-injuriously and as comfortably as possible, both hands still in front, Chuck turned his attention to dinner. It was amazing how hungry a person could get in virtual reality, and how satisfying virtual food could seem: in virtual reality, as opposed to life out in the reality of Papa’s Pride, any kind of food was programmable in any amount. Not only had Sir Ruthven’s brandy been good, but his larder seemed stocked with solid, well-flavored groceries. Suicidally inclined he might be, but at least not indifferent to creature comforts.

Chuck found a vegetable brush, rolled up his sleeves, and set to scrubbing potatoes for a quick ragout version of shepherd’s pie.

“I really would be interested to know,” said Sir Ruthven, appearing perfectly at his ease, now that doing harm was beyond his power, “why you prevented me from terminating a useless existence—alluding, of course, to my own, not to yours.”

“Negative thinking, sir. Your existence is far from useless.”

“In the deleterious sense, perhaps not. My loss would no doubt be a distinct gain to society at large.” The baronet shook his head and tsked. “Ah, Dr. Falcon, you have done society at large a grave disservice.”

Chuck decided to try a hint of what he suspected. “The reverse is true. I’ve saved society at large. If you ceased to exist, so would society.”

For an instant the baronet looked puzzled, as if trying to remember something. Then he smiled broadly. “Ah, a philosophical discussion!” He let out his breath and probably would have stretched out if the cord had not held him upright in the chair. “That society would cease to exist in so far as it touches myself is obvious; but that it would be a cessation to avoid is highly debatable.”

“I’m talking literally.” Chuck cubed the potatoes for quick boiling. “If you died, so would the world as you know it—people, rocks, grass, everything—gone. Not just as they touch you. As they touch one another.”

“‘No man is an island?’ Come now! Surely you’re attempting to carry the analogy of ‘the death of every man diminishes myself’ rather too far! In my case, the world would feel amply compensated for the diminishment.”

“You may think you’re being very humble,” Chuck said, tempering his short sermon with a grin, “but insinuating that the whole world is going to notice your particular demise is the most egocentric statement I’ve ever heard.”

“That’s it exactly!” The baronet appeared delighted. “I congratulate you, doctor—you’ve caught my character to a ‘T.’ At some season when it’s convenient for both of us, you must allow me to shake your hand.”

“But as it happens, your egocentricity is justified. I did mean it literally, about the world dying with you.” Locating a piped-in water supply, Chuck filled a small bronze kettle and added the potatoes.

“Ah,” said Sir Ruthven. “The famous theory called…well, I forget the name. ‘I (the cogitator) am the only thing that exists, and all things else are merely my imagination.’ But I refute this theory for three reasons, namely: First. If the world were entirely my own imagination, I would certainly imagine it a good deal more favorable to myself. Second. If this theory were true, I would, by definition, be God. But one of the attributes of God, again by definition, is omniscience; suggesting that if I were God, I should at least entertain some suspicion of the fact. Third. Granting this theory to be true, it should be impossible for me to destroy myself by any means—poison, dagger, noose, cliffs—all, being mere effusions of my own mind, should prove utterly ineffective against the only true reality, myself. But if you truly believed this to be the case, you would have no need to try to dissuade me from making the attempt.”

Chuck hung the potatoes on an iron hook over the fire to boil.

Maybe the most direct therapy—the full truth—might both effect a cure and gain the information they wanted—if Osborne was right, desperately needed—with no further loss of time and no further danger to anyone.

“Does the name Robert Lozinski mean anything to you?” said Dr. Falcon.

The baronet took a moment to adjust to what clearly seemed to him a sudden change of subject. “No…no, I think not. Should it?”

“It very definitely should.” Chuck found a flitch of bacon and began cutting it.

Sir Ruthven pondered a moment or two, apparently humoring his guest. “Robert was more or less my own chosen pseudo-forename for some years, but Lozinski…a foreign name, is it not? Japanese?”

“Polish.”

“Polish! There you have it—yet a fourth refutation of the famous theory (whatever it is called). If all things existed only in my own imagination, it should be impossible to surprise me with any new scrap of knowledge.”

Having chopped enough bacon, Chuck began on some leeks. “I could refute every one of your arguments, but I’m talking facts, not philosophy. I’m not trying to tell you that you’re God, or that the world around us is all there is anywhere. Because there’s a world outside us big enough to swallow us down and never even belch—a whole universe that’ll go on existing without knowing whether we’re alive or dead.”

“I notice you’ve begun using the first-person plural, Dr. Falcon. Are you including yourself with me in the putative creative mind, now?”

Dr. Falcon thought, Am I wrong? Is this Bob Lozinski? Still, having come this far, what did he have to lose? “I’m telling you that you’re no one named Ruthven Murgatroyd. Your name is Robert Lozinski, and at this moment you are lying unconscious, in a deep coma.”

Sir Ruthven looked startled. Then he smiled. “Am I comfortable?”

“Physically, as comfortable as good nursing can make you.” Yes, the virtual-reality equipment both of them were wearing “out there” really was pretty comfortable.

The baronet made an elaborately visible attempt to shift his position. (Not even the best hojojutsu could eliminate all physical annoyance.) “You’ve no idea what a relief it is to learn that. Might I ask how you know all this?”

Chuck put the bacon and leeks in the bottom of an iron saucepan and set it on a rack above the fire. “I’ve come here from that big world outside.”

Sir Ruthven cocked an eyebrow. “Some gentleman of science come inside my own brain to visit me?”

“Stripped of technical language, you might think of it that way.” Chuck’s own thought was, He’s intelligent, but I’m not getting through to him.

“I’ll resist the temptation to ask for the technical language, at least until we’ve dined on—why, I suppose we must call the contents of my larder literally food for thought!” The baronet leaned back and chuckled. “At least it’s a novel presentation of the theory of…whatever it is called. With all due apologies, Dr. Falcon, I hope that your culinary art is more substantial than your philosophy.”

Forcing a grin, Chuck began to carve the cold roast beef. He had lost the first round, but that worried him less on his own account than on Lozinski’s. Well, all he could do for the present was learn as much as he could of the young man actually before him, and meanwhile finish cooking dinner. Apropos of both projects, he remembered his earlier suspicion on failing to spot garlic among the kitchen stores. “My culinary art would be all the better for a little garlic,” he said with another grin. “Got any around?”

“Garlic?” Sir Ruthven glanced around at the spices and condiments in his line of sight, then closed his eyes and frowned. “Try that cupboard,” he said after a moment, pointing one forefinger. “The third shelf down.”

Chuck tried the cupboard. On the third shelf down, among jars and canisters of rice, dried peas, and other staples, he found a dozen heads of garlic. He broke off two or three cloves, returned, and chopped them fine before the baronet’s unperturbed gaze.

At least he wouldn’t have to worry about a bite in the neck. But he wished he had some way of knowing for sure whether those heads of garlic had been on that shelf before Sir Ruthven turned his mind to the problem.