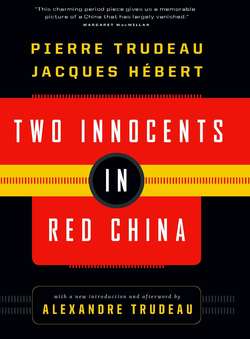

Читать книгу Two Innocents in Red China - Pierre Elliot Trudeau - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREAMBLE

This book was nearly given a different title: The Yellow Peril: New Edition, Revised, Corrected, and Considerably Enlarged by Jacques Hébert and Pierre E. Trudeau. This would have recalled to more than one reader the picture of China preserved in his subconscious: a land swarming with a multitude of little yellow men, famished, crafty, and (more often than they had any right to be) sinister.

Among all the terrors with which paranoiac educators sought to blight our childhood—freemasonry, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, Bolshevism, American materialism, the Red Heel, Chiniquy, and what else?—the Yellow Peril occupied a prominent place.

As schoolboys, we learned from missionary propaganda that China was the natural home of all scourges: pagan religions, plagues, floods, famines, and ferocious beasts. The periodic collection taken up for “stamps of the Holy Childhood” was also an opportunity to remind us of the wretched and slightly devilish state of a people who threw their babies to the pigs. And adventure tales featuring pirates of the China Sea or Fu Man Chus of the Shanghai underworld completed the education of our young minds in the dangers that lurked in the Dragon Empire.

It was during our adolescence that the Peril took on definite shape. College professors soberly proved to us, with statistics, that the demographic surge would soon burst the bounds of China and engulf the white world in a yellow tidal wave. About this time Mr “Believe-It-or-Not” Ripley was diffusing another arresting image: if the Chinese people marched past a given point in fours, the parade (taking account of the birth. and death-rates) would continue throughout eternity!

We don’t know if these images are still current today, or if children still advise each other not to breathe the tainted air if they pass an Oriental in the street. But we are compelled to remark that the adult world around us is unconsciously inspired by the same phantasms, all the more now that the Yellow Peril flies the red flag of Bolshevism. Under the influence of this dual fear, our conduct is doubly irrational: in politics we refuse to recognize the existence of those who rule a quarter—soon to be a third—of the human race, and we don’t deign to sit with them in the councils of the nations; in economics we hesitate to increase our trading relations with the most formidable reservoir of consumption and production that has ever existed; in spiritual matters we are perpetuating the established identification between Christianity and the most reactionary interests of the West, notably in linking the future of a certain kind of missionary effort to the (unimaginable) return to power of Chiang Kai-shek.

That China is still an object of fear is betrayed even in everyday conversation. Before our departure, people seriously told us: “You are courageous to go over there!” At first we thought this was mockery, directed against frivolous travellers by those who were courageously keeping their noses to the grindstone. But no; other expressions used taught us what daring we were apparently displaying: “Have you made your will? Accidents happen so quickly.” “It is easier to go behind the iron curtain than to come out again.” “Aren’t you afraid of being held as hostages?”

In all humility we couldn’t bring ourselves to take these stories seriously. Besides, we each had in our possession a document belonging to the Canadian government, in which the Secretary of State for External Affairs of Canada requested under his seal and “in the name of Her Majesty the Queen” that the authorities of “all countries” should “allow the bearer to pass freely without let or hindrance” and should “afford the bearer such assistance and protection as may be necessary.” Armed with such a precious safe-conduct, we didn’t see why we should be bothered at presenting ourselves at the border of any country at all. Besides, as the ensuing history is going to show, the Chinese took infinite precautions to ensure our return home safe and sound. They seemed to be afraid that, if one of us chanced to drown in the Grand Canal or idiotically fell off the Great Wall, a certain section of the Western press would draw dramatic conclusions about the danger of restoring diplomatic relations with a country where the life of a “French-Canadian Catholic” was held so cheap.

In reality the only fear that we might possibly have thought reasonable was that of being denounced and vilified by compatriots on our return ex partibus infidelium. And it is a fact that out of a hundred French Canadians invited to go on this trip the previous spring (true, this was before the fall of the Union Nationale government), fewer than twenty dared to answer, and more than half of them refused.

But it must be said that on this score the authors of the present volume were pretty well immune to reprisals by this time. Since both of them had been generously reproved, knocked off, and abolished in the integralist and reactionary press in consequence of earlier journeys behind the iron curtain, the prospect of being assassinated yet again on their return from China was hardly likely to impress them.

All in all, we two, who had never travelled together before but between us had been four times round the world, sailed nearly all the seas, explored five continents extensively, and visited every country of the earth except Portugal, Rumania, and Paraguay, discovered that we entertained the same outlandish philosophy of travel: we believed that those who have toured a country observantly and in good faith are in some danger of knowing more about it than those who haven’t been there.

And it seemed to us imperative that the citizens of our democracy should know more about China. If when we were children the grownups had told us anything besides rubbish on this subject, and if they themselves had ever been encouraged to reflect that the unthinkable sufferings of the Chinese people deserved something more from the West than postage stamps, opium, and gunboats, China today might be a friendly country. And an important part of Western policy wouldn’t have to be improvised in the back rooms of Washington and Rome on the basis of information gathered in Hong Kong and Tokyo by agencies that clip and collate various items from Chinese newspapers. So we thought some supplementary information, and an effort at comprehension, might be of some use.

It is true that, not speaking the innumerable Chinese dialects really fluently, we would be largely at the mercy (and it was a mercy!) of interpreters; that we would see only what the authorities would let us see; and so on. But the same reservations apply to the testimony of Canadian tourists in Spain, Egypt, or the Holy Land; yet nobody dreams of telling them that they would talk more sense about these countries if, instead of going there, they had kept their slippers on and stayed in Notre-Dame de Ham-sud or Sainte-Emilienne de Boundary-line.

For what has been seen has unquestionably been seen; what was translated was translated by a Chinese official interpreter, so that it does at least tell us what he himself thinks. Besides, we didn’t lack points of comparison: the combined total of our earlier sojourns in Asia came to nearly two years, partly spent in pre-Communist China and partly in Taiwan.

We know that to some people the mere fact of going to China and staying there at the expense of the Communists is enough to vitiate any testimony. Such people clearly rate their own and others’ honesty dirt cheap.

There remain some individuals with the peculiar notion that good faith towards China amounts to bad faith towards the non-Communist world. To this argument we have no answer, except that this is not the way we understand human nature. We don’t ask such people to read us or to believe us; and if they still persist in denouncing us we ask them first to reflect on the consequences of a purely negative anti-Communism.

For years anti-Communists of this kind have applied themselves to discrediting any evidence that might suggest that the Russians were not stone-age barbarians. Then, suddenly, the Soviets put gigantic Sputniks in orbit around the earth, photographed the other side of the moon, and confounded world opinion with their scientific progress. It is evident, then, today that Western governments would have done well to have listened more carefully to travellers who told of the progress of the ussr, and to have put rather less trust in the witch-hunters; for since it was our policy to regard Communism as an enemy or at least a rival, it would have been on the whole less dangerous to overestimate than to underestimate this enemy’s intelligence.

It is partly to prevent the repetition of these errors with regard to the Chinese People’s Republic that the authors have written the present work. Those who take seriously the precept “Love thy neighbour as thyself” cannot object to our reporting such success as the Chinese government is having in leading its people out of several millennia of misery. For it is always our fellow-humans that progress of this sort benefits—whatever their political allegiance may be.

But there will still remain some readers to accuse us—according to whether they are fanatically pro. or anti-Communist—of having said too much that is bad or too much that is good about today’s China. We accept this certificate of impartiality—and we nonsuit both parties. Let each of them console themselves with the thought that our testimony (if it is as biased as they will say) can only help to weaken their particular enemy by exaggerating his superiority!

And now, the journey begins.