Читать книгу Two Innocents in Red China - Pierre Elliot Trudeau - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION BY ALEXANDRE TRUDEAU

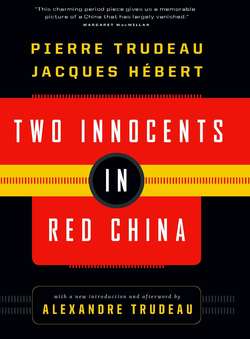

I was born to one of the authors of Two Innocents in Red China. I guess it is fair to say that I have always known about this book. Deep in the murky depths of my childhood memories, I remember, of all the things that might have impressed me about my father, being very impressed that he had written a book. How grand and mighty it seemed that my father had his name printed in large letters on the cover of an actual book. I have no memories of any other books that he had written, just this one. Perhaps I remember it because it was colourful and old-looking and even featured a picture of him on the cover. Perhaps because it had an odd title that I never really understood—who were these Innocents, anyway? Or perhaps it was because he had written the book with a friend, Jacques Hébert, who stood near him smiling in the photo, and the very idea that my father had friends like I did struck me as strange and somehow incomprehensible. Perhaps I remember that book because it was about China. Red China. And I knew about China. Though I was puzzled by the word “red.”

China is one of the first countries that I ever learnt about. Canadian children learn about China in the sandbox; it is the place that you will reach if you dig deep enough. They also learn about China when they find out what a billion is. There are a billion people in China, they are told. A billion people! My personal mythology linked me to China in another way as well. The idea of China as a place always accompanied that strange explanation that I had once been inside my mother’s belly. I was told that I had been in my mother’s belly while she was in China. That is quite a thought for a small child: in the belly in China! I later learnt that my parents had indeed visited China in October 1973; I was born in December.

I also remember that when my brothers and I were quite young, before we had started to accompany my father on official trips, he was gone for a whole month on a trip to China. To Tibet, in fact. It was the longest time that he had been away since we were born. We asked him why he was going to Tibet, and he replied that he was going because he had never been there before. What a mysterious answer that was! Maybe we too would go to Tibet some day, because we certainly hadn’t been there either. My father told us that Tibet was the place where the Himalayas were. They were the highest mountains in the world. It was also the home of the Yeti, a.k.a. the Abominable Snowman, and the land of Shangri-La, the most beautiful place in the world. At our cottage, we had an old map of the world on the wall, and my father pointed Tibet out to us. Under the name were parentheses and some script that said, “Occupied by China since 1951.” What did that mean? I asked. He told us that Tibet was part of China. But that it hadn’t always been.

Because it was his first trip away from us that I can remember, my father’s journey to Tibet fascinated me. It was not so much the place that stuck in my head but the fact that he had gone away, as far away as a place called Tibet, in China, where the mountains are. We waited for him and grew ever more excited as his return approached. And when, as predicted, he did indeed return, he looked and smelt different, which we hadn’t expected at all. He had a beard and a tan, and a strange energy about him. He radiated a kind of power, seemed more aggressive and alive than usual. It was as if his eyes still reflected the sights that he had seen, as if his body was still poised to meet them head on. This was a new father, not the patient and adoring father but the free spirit who had wandered the world. The lone traveller. The observer of things. The holder of secret knowledge. He brought with him a series of elaborately painted papier mâché masks and painted wooden swords from the Chinese opera.

For the first time, I began to understand what travelling was: going far away to places one had never visited but somehow needed to go to, and then returning home with strange and wonderful things, somehow changed, both inside and out. I had begun to grasp what my father meant when he said that he had travelled around the world and been to a hundred countries. More importantly, I had begun to understand why one travels. And, in my mind at least, I had begun to become a traveller myself. China became inextricably linked to travel.

ALL JOURNEYS START in the mind, with the desire, the need even, to go somewhere. In 1960 Pierre Trudeau and Jacques Hébert needed to go to China. And they had to impress that need upon their peers; in every sense, they argued, China needed to be recognized. “It seemed to us imperative that the citizens of our democracy should know more about China,” they wrote in the preamble to their book.

And so the Two Innocents set off to China. What, then, does innocence mean? Hébert and Trudeau never really explain the term. As a child, when I asked my father what the enigmatic words “deux innocents” on the cover of his book actually meant, he replied that he and Jacques were the two innocents. This explanation didn’t suffice, of course.

“How could you be innocent?” I prodded; “Innocent of what?”

“Innocent of not knowing any better,” was all that he added.

To this day, innocence remains a mysterious term to me. In French, especially, it has many meanings and interpretations. It is often used as a synonym for “simple.” Sometimes it refers to a child, candid and pure. It can imply both naiveté and wisdom—naiveté when applied to others, wisdom for oneself. It can describe both honesty and ruse. In a courtroom, the guilty often profess their innocence.

Most superficially, here is what I take the term to mean. Trudeau and Hébert were innocents. They wandered inadvertently into a serious place, frolicked a bit, observed all the strange and serious stuff that was happening, then came home and simply reported everything that they saw. They didn’t know where they were going, had no preconceived notions about what they would see. And they had no agenda, no axe to grind, so no one could accuse them of making things up, of having a plan or being biased. They simply didn’t know enough to have guile or guilt. That at least was their strategy.

“Innocence” could also be taken as a disclaimer for the would-be reader. This is not an expert book, the term says. In fact, real experts on China were a rare—even non-existent—breed back then. Hébert and Trudeau certainly never claimed to be great experts on China, before, during or after the trip. They point out, however, that they are experienced travellers, veteran observers of the world who are simply curious. They are not about to embark upon a lengthy or meticulous study of China; they are simply going to wander haphazardly into the place with open eyes and ears and take it as it comes. These “innocents” invite their readers to share in their youthful and optimistic curiosity, to accept that “those who have toured a country observantly and in good faith are in some danger of knowing more about it than those who haven’t been there.” What could be more innocent?

In truth, their innocence and implied lack of agenda were not entirely sincere. They were really more like a rhetorical stance, a plea of innocence addressed to the court of public opinion. Hébert and Trudeau did have an agenda. But their agenda was to rise above partisan Cold War propaganda, to transcend that simplistic dialectic that played capitalism versus communism, West versus East.

When Deux Innocents was first published, in 1961, China was far beyond the reach of even the most intrepid adventurer. It simply wasn’t accessible to the beatnik traveller or the dilettante globetrotter. The only way for a traveller to go to China was to be invited by the Communist government. Surprisingly, however, China did not hold back on invitations.

In 1960 the Western powers still considered the Kuomintang exiles on the smallish island of Taiwan to be the legitimate government of China. As they did for both the Soviet and, much later, the Cuban revolutions, they assumed that the Chinese revolution was only a momentary occurrence, to be quickly overcome by more Western-friendly forces. Many thought that it was only a matter of time before the Kuomintang Nationalists regained control of China. It would be 1972 before the United States overcame its wishful thinking and finally recognized the “transient” Communist Party as the legitimate government of the People’s Republic of China. Canadians should know that Canada had recognized China two years before Nixon’s bold trip to Beijing; Pierre Trudeau was the Canadian prime minister at the time. It is absurd, Trudeau argued, not to recognize a country of a billion people.

But ten years earlier, in 1960, Western governments were still a long way from considering the People’s Republic of China a legitimate nation, and the Communist Party was desperate for recognition. One of the Party’s strategies for obtaining it was to appeal directly to Western citizens. In the late fifties and early sixties China regularly issued invitations to Western business leaders and influential journalists and notables. The hope was that once these important people witnessed first-hand how functional Red Chinese society appeared to be, or at the very least how firm the Communist Party’s grip was, they couldn’t fail to report back that there was nothing ephemeral about Red China and that it might be time to consider recognizing its proper place among nations.

Few notables ever accepted such invitations. Most were downright afraid of putting their fates in the hands of China’s communist government. Others were more afraid of how such a trip would be perceived in their home countries. Trudeau and Hébert had no such fears. Both men were experienced travellers who had already journeyed behind the Iron Curtain. For their foreign excursions, broad political sympathies and their domestic activism, both had already prompted the ire of the extremely conservative Quebec establishment. Both were already labelled as troublemakers and outcasts. A six-week trip to Red China wouldn’t change much.

The two men were also curious. They were hungry for knowledge about this mysterious behemoth of a country and were open to considering other models of society and government. They were fond of discovering foreign innovations and habits and loved sampling strange new dishes. They also had a message to communicate to their brethren back in Quebec and were eager to provoke and belittle the province’s authoritarian and reactionary government. In this sense their book was very much an extension of Trudeau’s and Hébert’s polemical writing of the 1950s. Their “innocence” was a political message, a symbol of their indecent freedom. As much as possible, they would flaunt that freedom and use it to breach the dank walls of the cave in which Maurice Duplessis kept Quebec, flooding it with sunlight. An innocent travelogue through Red China was a perfect device for provocation.

China was not only scandalous because it was red. Trudeau and Hébert also point out that in the popular ethos of the time, China’s redness was just one among a whole litany of other outrages. In the book’s preamble they describe “the picture of China preserved in [the] subconscious: a land swarming with a multitude of little yellow men, famished, crafty, and (more often than they had any right to be) sinister.” China was the enemy, the cultural, biological as well as political enemy. Going there was a faint form of treason.

But by 1960, things were already changing in Quebec. Duplessis had died in 1959, and the Great Darkness of the Duplessis years finally came to a close with the election of Jean Lesage’s Liberal government in 1960. Quebec society was beginning to emerge from beneath the heavy mantle of the Catholic Church and its backward political patriarchy.

Of course, Lesage’s election slogan—“Maîtres chez nous”—had a nationalistic flavour to it. But it also carried an undertone of popular empowerment. The Liberals were urging the masses of Quebec to finally take responsibility for their institutions, to wrest control of their province from the narrow elites that had governed them since conquest. And these elites, though dominated by the Anglo and Scottish families of Montreal, were not entirely monoethnic.

On the periphery of the Anglo banking and industrial families of Montreal, a small French-Canadian bourgeoisie held sway over the liberal professions and the provincial political apparatus. The bastions and training grounds of this francophone elite were les collèges classiques, the rigorous institutions that the clergy used to indoctrinate sons of privilege. Virtually all Quebec premiers then and now have emerged from these schools.

Hébert and Trudeau were both from the privileged bourgeoisie of Montreal, both children of the rarefied urbane elites who had made most of the collective decisions for the French Canadians of Quebec for centuries. Both had studied at les collèges classiques. Both had also broken, at least superficially, with these elites.

Hébert, the rebellious son of a family doctor, became famous in the late 1940s for his weekly travelogues. For months on end he toured remote regions of Africa and South America, sending in colourful and humorous dispatches that made him a household name. At that time, apart from missionaries, Quebec could count very few world travellers among its own. Hébert not only travelled the world but also made it accessible. His accounts provided a unique window out of often dreary and insular French-Canadian society.

In the fifties Hébert became the editor of the hard-hitting weekly Vrai. In its pages he led spirited attacks against the Duplessis establishment and constantly berated it for its contempt for social justice and progressive values. In 1958 he founded the publishing house that issued the original edition of Deux Innocents en Chine rouge, Les Editions de l’Homme. For his part, Trudeau co-founded Cité Libre, a monthly magazine, in 1950. Through the next decade, it too would gain renown for its biting social criticism.

Hébert and Trudeau had become deeply suspicious of the concentration and corruption of power in Quebec and argued that a healthy society could only stem from a responsible and engaged citizenry. In their own lives, both men had already shown deeply adventurous and individualistic spirits. Both had forged their identities abroad as much as at home, and both were calling for greater freedom in Quebec. But neither saw freedom and empowerment as things to be taken by force from the hands of a corrupt elite. They had already developed a fair belief in the Canadian system’s inherent capacity for freedom. Yet each and every individual still had to find his or her own freedom, within him- or herself. An individual free of the shackles of habit and blind obedience could not be bent to the will of the exploiter.

Hébert and Trudeau had both flirted with socialism, and both had been involved in labour movements. But ultimately, their socialist leanings were not Marxist but humanist and, in Trudeau’s case, Christian. The model that they sought was that of a society of free men and women bound together by common responsibility. The narrative that they promoted was one not of class liberation, but of the awakening of the individual.

Although they were fierce in blaming Duplessis and his cronies for Quebec’s repressive regime, Hébert and Trudeau were equally vociferous in criticizing their fellow citizens for accepting (and voting for) this regime. Freedom was a mere matter of choice. They also sensed the longing building in their fellow Quebecers for a more open and progressive society. For them, the only real obstacle to achieving that society was the immobility of the people. They called on their peers to stop putting their faith in their political and clerical leaders and to take responsibility for their own fates.

In this sense, Red China was a symbol. Unlike many of the student activists of the late sixties, Trudeau and Hébert had no intention of proposing a Maoist system to their peers. What they proposed instead was a rational and responsible society without idols or taboos, one that could open itself to the whole world. Their journey to Red China represented the freedom to contemplate and reach out to even the most remote and maligned foreign entities.

MY FATHER RETIRED from politics with the explicit goal of spending more time with us, his children. He wanted us to go to school in Montreal, his hometown. He also wanted to show us the world in its varied shapes and colours. Through the late eighties and early nineties, my father, my brothers and I embarked upon a series of family trips to the “great nations of the world.” We completed these trips over the course of a few summers at a time when my brothers and I were still too young to be out travelling on our own but were old enough to comprehend a little of what we saw.

The time for these journeys was limited. So my father decided that our destinations would be constrained by the Cold War definition of the great powers: the permanent members of the United Nations Security Council. In the summer of 1984, we thus made our first journey through the Soviet Union, a mere six years before the waning empire began to break apart. We meandered our way south from Moscow to the Caucasus Mountains and as far east as the Amur River deep in Eastern Siberia. In the years that followed we made trips to France and the United Kingdom, the lands of our ancestors. In rented cars, we criss-crossed these old nations, staying at bed-and-breakfasts and budget inns.

In the winter of 1988–89, we decided that the coming summer’s trip should be to China. That spring, however, a dramatic protest began to brew in Beijing’s central and most important public space, Tiananmen Square. After the death of a beloved and open-minded Communist Party leader, Beijing’s university students began congregating in the square in ever greater numbers, demanding political change and democracy. They set up tents and camped out for weeks. Little by little, they were joined by more and more students from the provinces, and by intellectuals and academics. Eventually even some influential Communist Party members began turning out to the Square in support of the youth.

Like the whole world, my family watched these events on television with great interest. A month before the protests began, my father had contacted the Chinese authorities through the appropriate diplomatic channels and told them of his desire to visit their country, accompanied by his three boys. I remember getting increasingly excited at the thought of travelling to China at a time of great change. Even my typically impassive father was more and more stimulated by these events and by what they might mean for that summer’s trip.

My father had of course been to China several times before. He had made his first trip in 1949, just before the Communists finally routed the remainder of Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist forces and pushed them out of their last stronghold in Shanghai. He had seen China in the throes of massive change; perhaps he would witness yet another dramatic period of its history.

I was fifteen at the time, so my excitement was more than just an eagerness to see history unfolding before my eyes. I was also impressed by the charismatic young student leaders who were standing up to the venerable figures of authority in their country. I already felt inclined to stand up to authority myself. I had already come to believe, as I still believe, that the world belongs to those who seize it and that every generation has to seize the world anew.

Furthermore, as long as I could remember, my father had entertained us with tales of his worldly adventures. He told us of encounters with pirates and bandits, of his journeys through war zones and across endless wastelands. I had thus already made up my mind that to become a real traveller—a real man, one might even say—I too would have to live such high adventures. China in the middle of a huge nationwide protest—even, perhaps, a regime change—fit the bill as a good start-up adventure.

On June 4, 1989, after weeks of protest and terse negotiations between the student leaders and the government, the tanks of the People’s Liberation Army were called in, and the protests were violently quashed. The world watched in horror. At the Trudeau residence, our trip was suddenly called into question. Could we really still go to China? Would we still be received there? Did we even want to go after such a bloody and dramatic event?

The debate in the family was passionate. I remember suggesting that we still go. Damn the politics of appearances, I argued: we would be the only Westerners in the whole place and have the country to ourselves. The matter was eventually decided when the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs strongly urged us not to go, having recalled their ambassador in protest. I also seem to remember that the Chinese themselves admitted that it was perhaps not an appropriate time for visitors. And so our China trip was postponed.

The following year, I was insistent that we make our delayed trip. My father was still a little concerned about appearances: how would people view a former prime minister travelling to a country with which Canada had still not re-established relations? But he ultimately decided that this was a private family trip, made by private citizens to an ancient country. It needn’t have any political meaning.

So it was that in the summer of 1990, my father, my older brother and I set off on a six-week trip through China (my younger brother had since decided that he was more interested in summer camp than journeys with his family). Only a year after Tiananmen, the country still had some bleak undertones. But I did get my wish: there were practically no other foreigners to be seen anywhere. The tourist hotels were empty. Although the country had already embarked upon the road to economic liberalization and growth, some of the characteristics of earlier Chinese periods, such as authoritarian rule and a lack of contact with the outside world, had reappeared. The China of 1990 was more like the Red China of my father’s first trips than the economic powerhouse it would soon become. The winds of change had momentarily been stilled.

Despite my father’s plans, our trip was anything but private. We were treated as political guests and accompanied by officials and interpreters wherever we went. Every night, there were banquets and solemn toasts and speeches. When called to speak, my father would invariably refer very delicately to the sad difficulties that China had recently faced. He spoke of his hope that China and the West, which still had so much to learn from each other, would soon foster better relations. China is an ancient land with its own internal imperatives, he would add; outsiders simply cannot know what is best for China nor how it need travel down its chosen paths.

I learnt a lot during that trip. Not so much about China; the shadow plays of officialdom never interested me much. But I learnt a lot about the way my father viewed China and about the way he travelled. This was fitting, because this was to be the last of our family trips. The following year, I began hitchhiking my own way through North America. My own career as an adventurer, which has continued to this day, had begun.

There was something puzzling about my father’s attitude towards China. Why did he not dwell upon the Tiananmen incidents with our Chinese hosts? He wasn’t simply being diplomatic, avoiding tricky issues. In private, too, he behaved in a distinct and subtle way towards China. I had caught glimpses of this unusual behaviour at other times and in other places, but in China I witnessed him sustaining it for several weeks. “It is hard to know how China needs to move forward,” he would say. “Missteps in this immense country lead to death and suffering on a gargantuan scale.” It is not that he didn’t find the repression in Tiananmen Square grotesque—he did, he thought it arbitrary and wrong. But he would not let it shut dialogue down.

He was allowing for mistakes. It was very Socratic behaviour. In allowing the Chinese government the mistake of Tiananmen, he was accepting his own inability to change the course of things. He was professing his ignorance. Not gross ignorance, but the ignorance of a listener. Innocence. Not the political innocence that I mentioned earlier, but a more primal innocence.

My father first travelled to China in 1949, the year he turned thirty. After years of erudite studies at various prestigious universities, he drew the theoretical portion of his education to a close in order to devote himself to applying his ideas to the real world. It was time to test their mettle.

Long before, his father, a brawny and clever fellow, had made him understand that “book sense” could only carry a man so far; to succeed in the world, common sense was also vital. And common sense had to be acquired in the rough streets or the unforgiving wilds. Guided by his long-departed father’s wisdom, my father always tried to make sure that his ideas could survive the tests of reality. An impatient and ambitious young man, he was never going to wait passively for such tests to happen; instead, he went out and aggressively provoked them. He often seemed to be deliberately steering himself towards reality’s hard edges, then bracing himself for a crash. One might argue that he was not so much testing his ideas as building an unassailable carapace for them. Either way, he made harsh demands on his body and mind throughout his youth, to ensure they were ready to cope with adversity. He played hard, trained hard and sought out challenges, both physical and mental. He was a top student and an impressive athlete. Among his peers, he was reputed to be both a fierce debater and a razor sharp wit with the pen.

In his twenties, he tested himself further afield. He took the historical model of the legendary coureurs-des-bois, who he saw as the true heroes of the mental and physical wilds of yore. Like Pierre-Esprit Radisson, he endeavoured to canoe from Montreal to James Bay. “What sets a canoeing expedition apart is that is purifies you more rapidly and inescapably than others,” he wrote after that lengthy trip. He was already a traveller.

Through his twenties, he multiplied and diversified his trips. By canoe, by motorcycle or on foot, he bumped up against reality whichever way he could. He owned some stock in an Abitibi mining company and wanted a taste of its reality, so for a few months one summer, he got a job as a miner there.

In his meanderings in Quebec and Canada, however, whether in a mine shaft, in the wilds or in the city, my father was never challenged morally. He pushed his physical endurance to the limit but never went beyond the confines of well-established social values. He inhabited a world that he could depend upon. It wasn’t until his 1949 round-the-world trip that he would venture past those frontiers. Amidst the chaos that marked the beginning of the end of the colonial period, he quickly learnt that reality did not always need to be provoked—out in the wide world, its onslaught was both unending and merciless. In the Canadian wilds, he had deliberately deprived himself of physical and even psychological shelter, but he had never had to deal with the near total absence of all moral shelter. In his great journey of 1949 he found himself on many occasions without the protection of the rule of law, in situations where he had to rely for survival not on his own wits or strength of limb, but on a force completely beyond his control: the kindness of strangers.

In 1949, the old empires still exerted much influence across the globe. But as Europe’s great colonial armies gradually withdrew and its bureaucracies waned, its influence had weight only in the capitals, among the educated elites. The backcountry, the vast hinterland between the great cities, was the realm of the huddled masses. In 1949, any Westerner who got off a train in rural Iraq, India, Afghanistan or China found him- or herself face to face with the fragility of empire. The moral standards of the European metropole could not be invoked in the Arabian Desert, on the Khyber Pass or on the foggy banks of the Brahmaputra.

For the first time, my father had to perceive himself as an other.

It is on this trip that I believe my father really began to learn about innocence. For it is not the self-sure know-it-all who attracts the help of strangers, but the humble pilgrim in search of enlightenment. It is not a display of rigid principles that will invite kindness, but a display of vulnerability and openness. Thus he learnt the final and most difficult life lesson: to survive, one sometimes needs to be soft and supple, not hard.

I have also come to believe that no place made this clearer to my father than China. China was the tipping point. In 1949, the country was in the final stages of revolution. I remember him saying that the inflation was so bad that people had to bring wheelbarrows full of money to the market to pay for vegetables. Multitudes were starving. Crime was rife. There were no certainties, all was flux. In such an ancient and complex land, this chaos must have been totally overwhelming. By then, China had become all but completely detached from any outside world order. It was on its own. No education had prepared my father to begin to grasp how the revolution would conclude. The experience left him with a profound sense of awe for China, a mix of both fear and respect.

As much as he could, he moved through the pulsating chaos with the grace and litheness of a spirit. In other places, the paternalistic arrogance of foreigners prompted amusement or even gentle solicitude, but in China in the final throes of violent revolution, it only led to isolation, even hostility. My father could not be safe without the benevolence of the Chinese. He had to suspend his judgement, surrender it his dominion and accept China on its own terms.

This awe, this suspension of judgement towards China, never totally left him. Long before our family trip, my father had been forced to regard China as a great nation. China must not be sermonized, he concluded. The West’s impact on the world in the last few centuries may have been significant, but China has had an immense influence on the world for many more centuries.

China loathes outside interference. It won’t soon forget the humiliating treatment it received from the Western colonial powers in the two centuries preceding the Communist revolution. China also despises being judged. The Chinese have great respect for the tremendous intricacies of their age-old society. In everything Chinese, there are meanings behind meanings and incredibly subtle nuances and mysteries. The Chinese do not stand for outsiders passing quick judgement on things that we simply cannot understand.

His first trip to China had already made my father an innocent. His journey with Hébert would provide him with an occasion to preach open-mindedness to his fellow French Canadians by professing and promoting that innocence. Rising to address our Chinese hosts about the tragic incidents at Tiananmen, he was demonstrating that innocence once again, this time to his family. In his mind, Tiananmen was an aberration. Yet who was he to teach any lessons to China?

As a Canadian, my father was a stalwart defender of individual rights. He was a great believer in Canada’s parliamentary democracy—“the most civilized of governments,” he would say. He labelled himself a champion of the “Just Society,” which he thought was the only real objective a public figure could pursue. At home, he judged threats to and abuses of individual human rights very harshly. Yet he often seemed strangely philosophical when confronted with radically different values and systems of government. When he encountered these abroad, he sometimes remained silent about very obvious deviations from his own fiercely held convictions.

Yet for him, goodness and justice were not just subjective and personal—they were absolute. At heart, my father was no moral relativist. He truly believed that a free-market democracy (with a strong and socially engaged central government) was the system best able to guarantee the rights of individuals to pursue justice and goodness. Yet he also had tremendous patience, sympathy even, for systems and societies that had made (or borne) radically different choices.

Did China reveal my father to be an incomplete absolutist? A part-time Platonist? Or was he an absolutist only in theory and a relativist in practice? Could the traveller claim a metaphysical innocence? Was it possible to journey beyond one’s most unquestionable truths and then return to their safety without endangering them? Such enigmas are really at the core of innocence, and of my father’s fascinating and enigmatic love affair with China.

CHINA IS A VERY different place now than it was in 1960. When Pierre Trudeau and Jacques Hébert touched down in Beijing, they were entering one of the most isolated countries in the world. It was feared. It was poor. It was unknown.

Nowadays, China’s lightning-fast ascent and increasing impact on the world have become clichés. Simply put, China is a global superpower. Its appetite for resources and its astounding manufacturing capacity are transforming the planet’s economies. China is no longer the mysterious, distant and inaccessible pariah it was for several long decades after the 1949 revolution. These days, fortunes are being made in China on a daily basis. The intrepid adventurer has been all but replaced by the mundane business traveller and the pedestrian tourist.

But the lessons on how to travel found in Two Innocents are no less relevant today. China is still not an easy place to understand. One can meander the country soaking up the sights, as millions now do every year. They walk along the Great Wall, marvel at the Forbidden City and travel down the Yangtze. But they still have a hard time understanding what modern China is all about.

China can be frustratingly opaque. It is among the most inwardly directed societies on Earth. It moves fast and furiously, without explanation. China doesn’t stop for the Chinese and it certainly doesn’t stop for the foreigner. It can be downright overwhelming.

All foreign lands are puzzles. They reduce the freshly arrived traveller to a kind of innocence, a childlike state in which the basics of communication and movement have to be relearnt. In many parts of the world that alienation is relatively mild; in China, it is extreme. The sheer size of the place, the frenzy of activity, the deep detachment from Western ways make its puzzles much more difficult to solve, their every clue that much harder to discern.

Whether in 1960 or now, the outsider who seeks to understand China from scratch is faced with China’s three opacities. The most obvious barrier, the first opacity, is language. Few people speak any Indo-European tongue there, and outside Beijing and Shanghai, very little is written in English. Furthermore, the official language, Mandarin, is not easy to understand and is spoken fast in a variety of accents and dialects.

Things get lost in translation in China. Hébert and Trudeau constantly made mention of the difficulties of translation and went through a number of translators, French and English. During our family trip of 1990, my brother and I made a game of tracking the times our father’s gentle sarcasms were translated literally, causing confusion amongst our Chinese hosts. Sometimes we even pointed out the misunderstandings to him and urged him to make it clear that we didn’t actually mean to walk fifty kilometres to a temple or that the previous night’s lavish banquet had not in fact been “a tad informal.”

A translator is a kind of filter, someone who interprets and edits meaning while transmitting it. Too easily, he or she becomes an unwanted mediator. Communication and understanding find their surest foundations in a connection between personalities, in a trust built between traveller and host. And the true foundations of trust— our emotions, humour and anger—are often left out in a translated conversation. As they are squeezed through the dehumanizing prisms of translation, conversations are reduced to bland exchanges of information.

The second opacity of China is its totalitarian system. Much has changed since 1960, but the country is still governed by the Chinese Communist Party. Control of information and censorship have been pillars of the party ever since it took power in 1949. The party wants much of Chinese reality to remain opaque to the outsider.

From arrival to departure, visitors are treated to a controlled view of China. Just as the Two Innocents were allowed to see a very limited and specific portion of Red China—all that was most exemplary—modern-day visitors are also only shown a partial picture. For the most part, they are left to their own devices. But one way or another, all freedom—freedom of information, freedom of movement, freedom of exchange—is subtly limited.

Your average visitor may not notice these limits so long as he or she sticks to well-charted points of interest, but as soon as that visitor strays off the path he or she will be politely urged back onto it. This happens in an official way: at every place frequented by foreigners, there is always some guard or attendant to make sure that no one goes where they are forbidden to go, to politely but firmly tell a straying foreigner to return to the designated areas. But these barriers arise informally as well. Common citizens are mindful of foreigners who behave in too independent a way. They can be held responsible for the inappropriate behaviour of outsiders and are quick to “help” foreigners return to the fold.

At a deeper level, several generations of totalitarian rule in which ever-changing “universal truths” have been barked at them from above have trained most Chinese to keep their heads down, to be careful not to stand out from the pack. Being exceptional is to invite trouble. And any kind of meaningful or open exchange with a foreigner is by definition exceptional.

Things have been slowly and superficially changing, especially in the cities. Youth are behaving and dressing in more original ways these days. They are fully aware, however, that while it may be okay to dye your hair or get your navel pierced, openly discussing society or politics with strangers is still risky.

Censorship isn’t merely imposed by the government. Neighbours censor each other. Chinese society is politically organized, right down to the residents of a single floor of an apartment building. The Party is literally everywhere. There is always somebody watching. And if there isn’t, one side of the brain is watching the other.

This opacity can only be lifted with time and real intimacy. No one can censor him- or herself forever. But only a rare few travellers can linger for months or years, long enough to become “old-hands” and lift the veils of self-censorship. The more hasty need rely on various strategies to navigate through the socio-political quicksands of China.

Hébert and Trudeau’s innocence is, among other things, a strategy to encourage frank and meaningful conversation. Pretend to be a bit of a fool. Confine conversation to non-sensitive subjects that are revelatory in the long run. A good example of this is family; if you discuss a person’s family in enough detail, an intricate little picture of society emerges. Another strategy is to make innocent claims that, though benign, are so obviously false and ill-informed that your Chinese interlocutor is forced to correct them. In doing so, much may be revealed.

In a place like China, where one’s title and station are all important, another useful strategy for the traveller is to carefully frame oneself as something rather innocuous: a tourist, for instance. Never a journalist. The label of journalist immediately sets off alarm bells among both Chinese authorities and common citizens. Ideas shared with a journalist suddenly become more consequential, and thus people are less forthcoming. On the other hand, lying is risky; it is best just to choose some remote yet correct interpretation of one’s true identity. In Red China, for instance, Trudeau was declared a famous Canadian economist—probably for the first and last time of his life. As a result he was constantly paired up with “famous” Chinese economists.

Hébert, on the other hand, was accurately labelled a journalist. At the time, there was no question that Hébert the journalist might witness or report something that wasn’t properly prepared and packaged by the Communist Party. These days, the Party cannot possibly control everything a foreigner might see and is thus much more wary of journalists.

The final opacity that stands before the observer of China is by far the most subtle one. It is the assumption by virtually all Chinese that most foreigners won’t understand the truth about Chinese reality if it is presented to them. They believe that the outsider is simply not equipped to understand the whole of Chinese reality. Perhaps they are even right: so much of China happens under the radar, so much communication is indirect and metaphorical, so many truths are highly oblique and contextual. Even the Chinese need a lifetime of exposure and training to master meaning in China. Anyone who doesn’t speak the language, who hasn’t lived through a succession of political periods, who hasn’t faced and assumed the unspoken responsibilities of the son or daughter, of the pupil or citizen, can never grasp the truth of being Chinese. Only the Chinese can truly know the Chinese.

One might argue that this is true of all peoples and all cultures, that outsiders can never really know the truth of another society. But the Chinese honestly believe that their culture is by far the most ancient and sophisticated around, that the Chinese man or woman has absorbed a unique set of values that others will never be able to grasp. Few other cultures or peoples actually dwell on such an assumption to the extent that they completely change the way they communicate. Most cultures simply express themselves and let outsiders figure out what they will. But the Chinese sincerely believe that it would be foolish and inappropriate to even try to explain certain things to foreigners.

In practical terms, this means that on complicated and sensitive issues, the Chinese will rarely share all their thoughts with a foreigner. In many cases, they wouldn’t know how to properly express their innermost feelings and opinions to a foreign outsider. Sometimes they will adopt a different, simplified logic to avoid addressing difficult points.

This final opacity is immensely frustrating for the curious and audacious traveller. Innocence is fine when it is willed but bitter when imposed. How dare they decide how much I can understand about them, the traveller fumes!

Perhaps this is precisely why, from the very start, Hébert and Trudeau declared and embraced their innocence towards China.

HÉBERT AND TRUDEAU entered China through its great capital, Beijing. At the time, it was a great communist metropolis: immense, filled with workers, yet still low-lying, empty and austere. In the intervening years, change has come to Beijing like nowhere else in China. In many parts of the city, the places and people described in Two Innocents have simply been replaced by a completely different reality. But then as now, Beijing is the centre of the Chinese universe. In fact, the capital is arguably more potent and central to the country than ever before. It stews with its own specific flavours and habits, but somewhere in the mix is a little bit of everything you can find elsewhere in China.

In Beijing the Two Innocents visited the People’s Congress. They briefly describe some of the rooms representing the different provinces: “the Szechwan room, with its bamboo marquetries, its exquisite watercolours, and its ancient vases; the Kwantung room, with its teak furniture, its jade statuettes, its porcelain flowers…” Then as now in Beijing, you can visit museums or Party buildings where the various regions and ethnic groups of China are proudly displayed, wearing their traditional outfits, singing their folk songs.

As emblems of the radically diverse ways of life to be found within China’s immense borders, these formulaic displays come off as forced and phony. But they should be understood as celebrations of China’s unity, not its diversity. And is it so surprising that the Communists enthusiastically indulge in such symbolism, given that they alone have achieved a unity that had eluded China since early in the Qing Dynasty, a good three centuries ago?

In ancient times, parading peoples and things from the far reaches of the empire was a display of imperial might. And so it still is. The provinces and people on show in the capital are proof of the central government’s hold on all the regions of China. There is even an element of competition, whereby each group stresses its own crucial importance to the totality of China and Chinese history. Thus all these far-fetched energies and passions descend upon the capital as a radiant symbol of the Chinese people, ancient and united.

These days, the notion of Beijing as the focal point of a vast but deeply united empire is further enhanced by the upcoming Olympics. Because of the Games, China is being brought to focus even more clearly in its capital. In Beijing, the peoples of the world will be China’s guests. This is completely unprecedented; historically, the Chinese have been more accustomed to outsiders invading their country than visiting it. Foreigners such as Marco Polo were entertained by the courts of the ancient emperors, but these early visits were sporadic and of limited value to the Chinese.

The Olympics, on the other hand, are all important for the New China. The entire world will show up in Beijing as honoured guests, not hungry invaders or colonizers. The world will thus recognize China and pay it homage. The games will be a celebration of unity and a demonstration like no other of the prominence Chinese society has now achieved on the world stage.

Hospitality is the greatest luxury one can offer. Hosting others testifies to one’s wealth, to one’s command of one’s home. By hosting the entire world in its capital, by overwhelming that wide world with its majesty and its dominion, the New China—for so long reviled, rejected and outcast—will declare its oneness, its might and empire.

The city has already begun its metamorphosis. A new national symbolism is being put on display. Buildings surpassing even the greatest halls of Red China are being quietly erected across the city. The immense new Olympic Stadium, woven together with countless spidery steel girders, is both beautiful and slightly terrifying. An enormous bubbly and translucent box will house the Olympic swimming pool. For the moment, these monstrous buildings are totally inaccessible. They are phantom structures, seen only from a distance, veiled in smog. Legions of unknown workers from the far reaches of the land have been brought in to toil anonymously in their construction. The vast sites are forbidden cities whose power has not yet begun to radiate. Yet already they strike awe across the capital.

In many ways, the Forbidden City proper sits outside of China. It is now a pen in which to hold foreigners. They are driven through it like so many heads of cattle. Is it possible to see the Forbidden City properly? Can the past be seen in the present? The Palace of Knossos, the Karnak Temple, the Forbidden City, these monuments were all built with a purpose. In their day, they were deeply useful. The visitor can still marvel at their surfaces but cannot really penetrate them without feeling the power of their purpose—and this is long gone.

The Forbidden City was a supremely orderly place. It was a tool of obedience and worship. It was also far more important from the outside than from the inside. The Forbidden City was so powerful because it was closed. It was the unattainable nucleus at the very heart of the Middle Kingdom, itself the centre of the Earth. And it was never meant to be open for contemplation. Pedestrian access to the holy sanctuary would have been a fatal breech in its sanctity.

Those who had access to the City—and then, only to its majestic outer courtyard—marched into it in strict formation, through a long tunnel under the massive fortress at the southern end. In ranks and columns, the summoned were lined up on the immense cobbled square beneath the appropriately named Hall of Supreme Harmony. There they awaited word from above. This was a place to be stripped of one’s particulars, one’s name, a place to receive orders to march into battle or enact a new imperial policy. Here stood the tools of Empire, not individuals or men but peons whose very lives and destinies were selflessly subsumed into the higher cause.

Almost a prisoner of the City himself, the Emperor was born into celestial servitude and bore the heavy mantle of a heavenly mandate. In his servitude to harmony, he was no different from his subjects. Harmony meant being at peace with one’s station, embracing it wholeheartedly whether you were the Emperor or the lowliest peasant.

On a cold and rainy day, you may still be able to march into the empty City and feel its old soul pulsing in the solitude and silence. But the modern soul of the Forbidden City is elsewhere. Beijing is still the seat of power, and the centres of power in the capital are as inaccessible as ever. The Forbidden City is now open, but the real centres of power are still closed.

Today, the mysterious face of Mao gazes out impassively from the main gate of the Forbidden City. More than anyone else, they say, Mao changed the nature of power in China. In truth, he didn’t so much change it as move it. Through the first decades of the twentieth century, the Chinese had already begun rejecting the imperial rule that had ended in such decadence and humiliation. The country became polarized into two distinct political outlooks: Communism and Nationalism. Both proposed a break with the decrepit practices of imperial China. The Nationalists wanted to form a government that would represent the modern aspirations of the emerging Chinese bourgeoisie. If the elites took the lead towards modernity and progress, they argued, the rest of China would eventually follow. The Communists proposed something far more radical. They dreamt of a government that would reach out immediately to the entirety of the Chinese people, the wretched and the poor. They hoped to replace a cruel, closed, fragmented and hierarchical society with a levelled-off nation belonging to all.

The Communists came together as a party slowly, over a generation. The party formed as a collective of individuals from all over the country, all moved by this radical idea of a people’s republic. The first leaders—daring, dissatisfied, inspired—came from the educated bourgeois classes of the big cities. With time, sons of landed peasants joined the movement. The brilliant and ruthless young Mao Zedong was one of the latter. Groups began to multiply and grow across the countryside. The rarefied Chinese establishment, dominated by the Nationalists, immediately saw them as a threat, and a long period of clashes and battles began. From 1927 to the final victory of the revolution in 1949, Mao became ever more successful at winning these struggles.

Under pressure from the Nationalist armies, a number of the emerging Communists gathered in the south. Pursued, they walked and fought their way north, halfway across the country, absorbing followers from the heartlands as they went. This was the legendary Long March.

Throughout the thirties, the Japanese had been aggressively encroaching on Chinese territory. They occupied Manchuria in 1933, and with the advent of the Second World War they began to express their violent designs for the whole of China. Working their way down the coast, they pushed the Nationalist armies south. As they moved further inland, the Japanese then encountered the Communists, who formed a wall of guerrilla resistance for eight years. So long as the Communists wore away at the Japanese, the Nationalists let them be. And from the Communist point of view, so long as they had to fight the occupiers, they left the home-grown oppressors alone.

With the end of World War ii, the Nationalists and the Communists resumed their fierce struggle. The big showdowns took place in Manchuria. By the time the opposing armies faced off in the north, the Communists had grown substantially in number. On the battlefield, hundreds of thousands of Nationalist troops deserted and joined the Red Army. The Communists dealt the Nationalists a crushing blow. With this momentum, the Communists swept across the country, absorbing the whole of the Chinese people.

With such a long and convoluted path to victory, it cannot really be said that the Communists were easterners or northerners or southerners. They had picked up members from all over the country. The Communists, vast legions of them, were Chinese. And by the time they acceded to power in 1949, their uncontested leader was Mao Zedong.

To institute the radical reforms and nationwide restructuring measures that he believed would propel China towards inexorable self-sufficiency and social harmony, Mao came to believe that a strong central governing body was necessary. Almost sixty years later, communism, the original ideology of the revolution, exists in name only. But the central governing body—that tremendous unifying power, the Communist Party—remains. This is the real legacy of Mao’s reign. The government Mao created is the new Forbidden City of a one-party dynasty. Its true location and form are as mysterious now as they were when the Forbidden City still struck awe across the land. Today as ever, no one can say from where China is governed. No one knows where the real decisions are made. It is even hard to gauge the actual power of the president and the premier. They stand at the top of a hierarchy of appearances. What lies beneath is forbidden and unknown.

TRUDEAU AND HÉBERT visited China in the fall of 1960, smack dab in the middle of the Great Leap Forward. Mao had concluded that peasant force alone would not safeguard China from its enemies. He had also decided that China must be able to satisfy the entirety of its various appetites on its own. He thus enacted a series of radical reforms aimed primarily at the countryside. Mao dreamt that the countryside would become the new centre of industry, a diffuse and inexhaustible source of essential products.

And so farmers were told to build iron smelters. Villages across the country were integrated into a national campaign for rapid self-sufficiency and slapped with impossible production quotas. Not only did the rural population fail to produce anything close to the quantity or quality of goods necessary to turn China into a modern industrial power but, distracted from their farms, the peasants began to experience massive food shortages. The Great Leap Forward caused a great famine.

At the time, the Communist Party so tightly cloaked the countryside from sight that visitors like Hébert and Trudeau could not imagine what was happening in certain parts of China while they toured other sites. To this day, the Party has made it impossible to fathom how many people really died in the famines caused by Mao’s Great Leap Forward. Thus the Party survived the first great catastrophe of its reign.

It is said that the emperors of China governed the land by virtue of a heavenly mandate. As such their authority was sacrosanct. But the mandate also meant that, through the Emperor, the people were the benefactors of heaven’s blessings. The Emperor was beyond reproach, but only so long as his rule was, by and large, beneficial for all. If it was not, the Emperor clearly did not have a heavenly mandate, which meant that he could not be the true Emperor of China. So ended many dynasties.

Things are no different today. In the decades immediately after the revolution, most Chinese people embraced the Communist Party, because it had united China and formed a wholly Chinese government for the first time in centuries and also because it offered a new hope to the poorest class: the landless peasants, hundreds of millions strong. But by Mao’s death in 1976, the Communist Party was ideologically bankrupt and close to collapse. Too many great experiments had gone desperately wrong. The people had begun to sense that the heavenly mandate was on the wane.

Two major changes shored up the Party’s mandate to govern. The first was a thawing of relations with the West. Stunned by American defeat in Vietnam, social strife at home, humiliating expulsions from former colonies and the continued radiance of Soviet power, the Western powers became more realistic about their global hegemony. Seeing that their dominance was no longer total or inexorable, they became more open to negotiating with hitherto snubbed rivals.

Shortly after the revolution, Mao came to see Soviet involvement in China’s affairs as a particularly insidious form of foreign domination. And so he led the way in establishing a third pole of world power: the non-aligned movement. By the seventies, China was thoroughly at odds with the Soviet Bloc.

But the Western powers could not afford to be at loggerheads with both the Warsaw Pact countries and the non-aligned nations, and they saw the former as a far greater threat. China was both an enemy of the Russians and the natural great power of the non-aligned movement, so the Western powers gambled that a rapprochement with China would be in their interests. More subtly, they guessed that by elevating China, they would also stall the growing non-aligned movement, which would lose its natural leader.

So at the very time that the Communist Party of China, controlled by increasingly irrational ideologues, was beginning to lose the mantle of the heavenly mandate, the West offered China the recognition it had craved for so long. China was invited to join the table of superpowers and was granted permanent membership on the United Nations Security Council. The People’s Republic suddenly had new grounds to claim legitimacy.

The second change that shored up communist authority took place within the Party. Faced with the catastrophic famines brought on by the Great Leap Forward and the insane purges of the Cultural Revolution, a group of respected elders fought against the more orthodox Maoist core of the party to introduce another benchmark for legitimacy: prosperity. They also used their influence to elevate a critical mass of younger cadres that might become agents of reform. The party had to find ways to create wealth. With Mao’s gradual withdrawal into senility, his right-hand man, the wise and venerable Zhou Enlai, allowed this reformist movement to survive in the face of fierce opposition within the party. But it was the old revolutionary peasant Deng Xiaoping who eventually ensured the movement’s success. In so doing, Deng became the Communist Party’s dominant figure after Mao Zedong.

The pursuit of prosperity—the logic that Deng finally made inevitable in the late seventies—has held to this day. Prosperity may even have eclipsed the other virtues of communist power in China. And for more and more Chinese, prosperity has become the only benchmark for legitimacy. These days, Communist Party rule will be tolerated only so long as it creates wealth.

The new wealth is overwhelming in the big cities and undeniable in most towns. But if it doesn’t trickle down to the hundreds of thousands of villages of China, the claim to the celestial mandate will find three quarters of a billion detractors. And prosperity does seem to be reaching the countryside. Villages are more connected than ever before. A village may be extremely remote, but it is now linked to the rest of China in a whole variety of ways, both wired and wireless. In even the most far-flung hamlets, people now use cell phones. And with the huge migration of workers, every village is also still home to individuals hundreds of kilometres away, living in dormitories or camping out in makeshift shacks and toiling away in factories or on huge construction sites. In its own little way, each village is an active part of the whole, a wellspring of food and labour.

In accordance with the heavenly mandate to govern, the Chinese government must bring some blessings upon every little village and its people. So over the last decade and a half, the government has connected countless villages with the rest of China. They have brought electricity and telephone wires and beamed in television signals and mobile communications. When necessary, they truck drinking water in for the people. Eventually they will build proper roads to most of the country’s villages to make it easier to deliver water and extract the fruits of the land. China is reaching into its bosom, both taking and giving, becoming more united than ever before.

China’s dual residency system governs the delicate balance between the cities and the countryside. It creates a subtle but powerful barrier between the two. Under this system, all Chinese citizens must have a residency permit stating where they live. City dwellers can obtain permits for wherever they choose to live fairly easily, but it is extremely difficult for the rural poor to obtain permits to inhabit the cities. One often hears of the hundred million homeless people in China. This number actually refers to all those rural residents who have migrated illegally to the cities and thus cannot have official addresses there. These people, commonly referred to as migrant workers, make up the brunt of the workforce in the new manufacturing centres of China. Their illegal status in the cities puts them in a particularly precarious position vis-à-vis the law and makes them a highly docile and timid workforce.

The Chinese authorities are well aware of the social tension induced by such a system. But they also recognize that the malleable workforce it creates is one of the main factors driving China’s lightning-fast development. Theirs is really a containment strategy for the rural populations: keep them in the countryside, allow just enough of the rural population out of the hinterlands to fuel the manufacturing sector’s need for cheap labour, but deny these migrant workers any real status that might make their presence in the cities more permanent or powerful.

PRESENT-DAY BEIJING preserves much of its classic layout. It is arranged in concentric rings around its nucleus, the Forbidden City. The First Ring is rather vague and hard to define; it works its way around the huge moat and walls of the Forbidden City, through the old imperial quarter once composed of official compounds and warehouses, now more and more made up of tourist shops and restaurants.

By the Second Ring Road, one is more properly in China. This road marks the old walls of the city; the entire Ming Dynasty capital sits within its confines. Here are the ancient living quarters, crammed with traditional abodes called hutongs. In the tiny, tortuous streets, China goes about its way. The residences themselves are hidden behind ten-foot walls. Behind some, eight families dwell in stone or concrete houses around cluttered central courtyards; behind others, a single general or party leader lives with his family amidst tranquil gardens. But in the open lanes, it all mixes together. The bicycle squeezes by the black Mercedes and dodges the vegetable cart. Newspaper in hand, grandpa shuffles his way past it all on his trip to the public shitter for his favourite moment of the day. Grandma and grandson head to the temple to light prayer sticks for grandma’s parents, long gone but not forgotten.

The Second Ring also houses the seats of power. Symbolically, Chinese power dwells in the great halls around Tiananmen Square, just outside the Forbidden City. These are the People’s Palaces and, of course, Mao’s great mausoleum. But the real power is elsewhere. It is scattered across the hutongs, somewhere behind those ten-foot walls.

Between the Second and the Third Ring roads, capitalism has come to blows with communism. For centuries, the city beyond the walls has been the area where various folk from different regions and callings have gathered to answer the bidding of the powers of the day. Soldiers, merchants, foreigners and workers, the people within the Third Ring have always been the tools of the establishment. Their descendants remain. Understandably, the communists took vigorous control of this quarter after the revolution. They housed their workers and their soldiers there and built factories and schools and laboratories—everything they needed to govern Red China and triumph against its foes.

The transformation of this area over the past decade may be the single most significant symbol of change in all China. Communism may not be dead, but within the Third Ring, it has lost the battle against capitalism. All over the area, office towers are taking over. They house the money: the state companies, the Chinese businessmen, the foreign investors and the multinational trading companies. The power of the New China resides in its immense economy, partly free, partly planned. And this economy is managed within the Third Ring. Here, amidst the glass towers and concrete skyscrapers lit up by so many logos of commerce and consumption, the New China glistens. China was once red. Now it is many colours.

During one recent visit to China, I rode a bicycle along the Second Ring, a broad avenue built where the old walls of the city once stood. To my left as I pedalled was the New China skyline; to my right was the old Ming city. Naturally I was more enchanted by the ancient neighbourhood I was circling than by the thick maze of corporate headquarters and business hotels surrounding it. At one point, I stopped in the hutongs just off the Ring to get my squeaky bicycle chain lubed up at an old blacksmith’s shop. The ragged area jutted right up onto the road and was sooty, cramped and authentic— quite the display from the modern highway.

I returned to China a few months later to be surprised by an abrupt change in the cityscape. Gliding along the Second Ring in a taxi, I suddenly realized that the blacksmith’s hutong was gone. An area two arteries deep into the old city—hundreds of shops and houses, little laneways and ancient trees—had been wiped off the face of the Earth. In its place a pleasant park had been installed. By installed, I mean that it had just appeared out of nowhere: big old trees, lawns and flower beds, park benches and moody lighting, even little sections of old stone wall that provide pleasant little obstacles for walkways to wind around. The illusion of permanence was so great that I asked the cab driver if the park was in fact new or if my mind was playing tricks on me. “It is new,” the cabbie replied with a knowing smile. Perhaps even a little proud of what his government can do.

Gone. I started to imagine… Gone are the blacksmith and his shop. Gone is the poultry seller. The old widow and her minuscule home behind the barber shop. Gone. All gone. Gone and forgotten?

Like everywhere else in the world where prosperity has become the great motor of society, so much of old China and its ancient ways seems to be disappearing. The very real estate they occupy is being reclaimed for new purposes, for the new prosperity. The ragged and dirty spaces are being paved over. If possible, their inhabitants are incorporated into new realities; if not, they are sent to live out their lives in small concrete apartments on the edges of the city, preserved in obsolescence. A few rare artifacts like the Forbidden City, emptied of all purpose, are preserved for the tourists.

What then has become of Red China? What has become of the strange mirage of a place into which Hébert and Trudeau ventured so innocently and which you, dear reader, are about to enter? From the beginning of their adventure, from the first sips of tea over terse negotiations with a consular official through the bizarre visits to factories, the impenetrable conversations with bureaucrats, the Marxist orthodoxies, the tremendous pretense of order and rationality of the planned society, the China that Hébert and Trudeau visited seems to have disappeared without trace, like that quaint blacksmith’s hutong.

But you are not about to read a book about an extinct way of life, a vision of some strange and implausible reality filed away in the memory like a fossil on a shelf. The amazing thing about Red China is not that it was and is no more but that, like Ming China or Han China before it, it has slowly been sublimated so that now it is part of the foundation upon which the New China stands. The Red was not washed away before China was repainted in all its new colours. The Red can still be found, muted beneath all of the new hues.

If China has lasted so long, perhaps it is because nothing that has come before is ever truly lost. Like all old societies, China has progressed by addition. All its past meanings and colours still exist somewhere, deep in the memory of its people. They are all part of the great and mysterious world that is China, a world that demands for itself both unity and perpetuity.

Even more than the Red China upon which it was built, the New China deserves to be understood. Its global resonances are only beginning to change our habits, our cultures, our economies, possibly even our climates. More than ever before, we Westerners will be challenged to take a position on China. But it is a place that is both unified and incredibly diverse. There will always remain much here that we will find odd, opaque, even ominous. Yet the lessons of the Two Innocents call out to us as clearly as ever: do not become transfixed by fear, by irrational fantasies of what China was, is or will become. For fear would close us off to China. And China—in its immense and growing prosperity, enormous production capacity and huge unanswered hunger—is already upon us.

Our societies will be better served if we reach out to China, happily and innocently, if we explore its depths, marvel at its opacities and idiosyncrasies, and yes, occasionally tremble with awe at its rumblings and missteps. Instead of fearing China, we should share as much as possible in the great adventure of its people.

For the West and China will never overcome each other. Nor should they ever stop learning from each other.