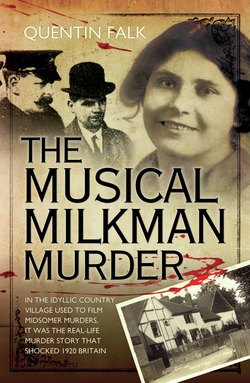

Читать книгу The Musical Milkman Murder - In the idyllic country village used to film Midsomer Murders, it was the real-life murder story that shocked 1920 Britain - Quentin Falk - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеThis story, as so many stories often do, began – or, more properly, first took shape – in the manner of a Chinese whisper, when you aren’t quite sure whether its repetition is an accurate account of the original telling or else just an increasingly mangled version of that initial truth.

When my father bought back Old Barn Cottage in 1966 after it had been out of the family for 23 years, I was vaguely aware of some of its dim, distant history known locally, and lip-smackingly, as ‘The Musical Milkman Murder’. But who murdered whom – was the milkman the murderer or the victim? I didn’t know and wasn’t even particularly concerned to discover at the time.

All I think I knew then was that the killing – whether by axe, shotgun, strangulation or poisoning – apparently occurred a couple of years before my paternal grandfather, Lionel, had first purchased the place, then known as plain Barn Cottage (he later added the ‘Old’) for £700 as a weekend retreat from the family’s North London home in 1923, before selling it in 1943 (for £1,800), at the height of the Second World War.

Our first real inkling of its infamous past came in the very early 1970s when some neighbours spotted a middle-aged woman standing outside the gate looking at the place with sad eyes. They approached her discreetly and helpfully informed her that none of the family who owned the property was currently in residence. They then enquired why she was staring so intently at the rose-covered cottage, a pretty cliché of Buckinghamshire brick-and-flint, adorned with gables and criss-crossing Elizabethan timbers, dating originally from the turn of the 17th century.

She told them that, years ago, there had been a murder there. Yes, they replied, they knew of it, although they didn’t have any of the real facts of the case to pass on to her. Then, to their stunned surprise – and later ours when the news was relayed to my father and his family – she told them that her father, the milkman, had murdered her mother Kate, and that she, Hollie, just two at the time, was their surviving child. More shockingly, Hollie – probably aged about 54 as she revealed all this to our increasingly astonished neighbours – then told them that she’d only very recently discovered the terrible truth about her dead parents via an anonymous call.

Growing up first with her father’s sister and then with her paternal grandmother, she had always been fobbed off whenever the question of her parentage arose. All she had been told was that they had ‘died from the fever’. She remembered vividly once asking her aunt whom she was most like – her father or her mother? ‘Your father,’ came the chilly reply. End of conversation.

When, following the stark revelation about her parents, further elements of the truth began to filter out – that Hollie had been born in the infirmary of Winchester Prison, the possibility of a botched suicide pact, and so on – Hollie, by now on her third marriage and the mother of five children, as well as grandmother of increasingly more over the succeeding years, wanted finally, desperately, to nail down the real facts of the case. Her first port of call – after first making contact with Births, Marriages and Deaths at Somerset House – simply enough, was the location of the final resting places of her father and mother.

To Mrs Hollie D from the Governor of HM Prison, Oxford, 10 September 1973:

Dear Madam,

Thank you for your letter of 9 September. It is confirmed that a George Arthur Bailey was executed and buried at this prison. As regards your mother, I am unable to assist you. I advise you to write to the Registrar of Births and Deaths, Somerset House, London WC2 to find out the date of death and the parish in which she was buried and using this information to write to the Vicar of the parish concerned for information regarding the location of the grave.

Two days later, the Governor of Oxford Prison wrote again to Hollie in response to a note the day before asking if she could visit his grave: ‘Thank you for your letter of 11 September … I am sorry that it is not possible to allow visits to graves in the prison. I hope you are successful in tracing your mother’s grave.’

Whether she was pointed in the right direction by Somerset House, one doesn’t know, but, on 26 September, she wrote to Buckinghamshire County Council for information and received an extremely swift response from the Superintendent Registrar referring her next to the local vicar at Little Marlow – and he even enclosed a stamped, addressed envelope for the cleric to reply.

On 11 October, she received the following from Rev John Crawford, Curate of St John the Baptist, Little Marlow: ‘Thank you for your letter. The number of your mother’s grave in Little Marlow Cemetery is No 256; burial on 6 October 1920. The numbers are all lost or misplaced so it would be hard to locate but it is in the oldest part facing the chapel door. Wishing you every blessing in the future.’

In November, she wrote to the Editor of the News of the World, Cyril Lear, asking if he had any back copies of the paper for 1920, the year of the murder. Her approach to the paper specifically may have been to do with the possibility that the anonymous tip-off about her parentage had originated from that now defunct Sunday newspaper. He politely replied that he couldn’t help but suggested instead that she contact the Newspaper Library at Colindale, which continues to store a remarkable collection of national and regional newspapers.

The trail then ran cold, it seems, until it became apparent, in March 1974, that Hollie had made contact with my father, eight years after he bought back Old Barn Cottage; she had sent him what few bits of documentation about the case she’d managed to track down. He invited her to tour the cottage properly and she sent him this letter, after her visit, on 29 March:

We were very pleased to meet you, and thank you for your kindness in letting us look over the cottage. I felt no sadness. I was three years old two days after my mother was buried. I always wanted to know where my mother was buried; as you can see, I only found out last year. My father’s mother brought me up. I was brought up to believe that it was meant to be a triple suicide, but my father lost his nerve and it was only my mother that died. I know he was hung at Oxford Prison. I excepted [sic] that. My grandmother died when I was nearly 17 years old. I was left to make my own life. When I received my mother’s death certificate last year, I knew there was more than I had been told. When I wrote away to the London Library and received the papers, I was shattered. My tears were for my poor mother, only 22 years old and 7 months pregnant …

Hollie then concluded her letter by also thanking my father for his offer to her of a ‘job looking after the cottage … but my husband’s job has a pension at the end of his retirement. But I will certainly keep a look out for someone for you.’ This came as a huge and somewhat unsettling surprise to me; my father had never told me of this in his lifetime (he died in 1997 aged 86), and I hadn’t seen the reference until I started researching this book. This was the same year I had moved into the property full time, after the place had been, for the most part, a family bolt-hole for weekends and holidays since 1966.

A month after her visit, my father wrote to Tony Church, Editor of the Bucks Free Press, the most widely circulated local paper, asking if it would be possible to obtain copies of the contemporary coverage of the case and the trial in 1921. Church replied: ‘With reference to the Bailey murder at Little Marlow, back in 1920, I recall that we did have an enquiry from the daughter some months ago and that from the rather vague details she had we were able to trace the report of the murder and the subsequent trial proceedings and that we were able to give her information that has obviously led her to make the rather melancholy visit to Little Marlow. But, as you say, no doubt it has helped her to lay a ghost.’

In due course, whether via the BFP or the Newspaper Library, a full set of Bucks Free Press reports came into our family’s possession before being rolled up into a tube and forgotten for another 30 years or so.

At the beginning of 1975 – and a month before I got married – Hollie wrote again to my father, reflecting, ‘It has been a very depressing kind of year for me. If only I had known when I was younger, perhaps I could have forgotten it better. As it is, I shall never be able to forget. Perhaps time will help. I can only think my father was a psychopath.’

She then went on, ‘The last time I visited the grave, there was a notice board up by the plot of ground where my mother is buried saying that in September this year they are going to level the graves over and, if anyone is interested, to get in touch with the council concerned. I have given it a lot of thought, and think the best thing I can do is to let them level the grave over, and let things be forgotten, or try to. I shall visit the grave once more.’

My father wrote back to Hollie two days later, on 9 January, sympathising about her ‘horrible year’ before telling her that the cottage was soon to become a lovely, permanent home for the happy couple – ‘I only wish that your associations with it were happier. You know that there will always be a welcome for you should you come to the village and provided you give us a little bit of notice so that we are sure to be there.’ That was his last ever direct communication with her.

However, nearly ten years on, in 1984, in response to a request by the Midweek edition of the Bucks Free Press, which felt the case was worth revisiting all these years later, my wife and I, now parents of two young children, took 66-year-old Hollie on a tour of the much-refurbished and considerably re-jigged cottage, certainly compared with the 1920 version or even, for that matter, the one my father had walked her round a decade before.

On, quite inappropriately, Valentine’s Day, Midweek published a lavishly illustrated account of her visit to the cottage and the cemetery written by its chief reporter, Bob Perrin, under the cheerful headline: ‘A WOMAN ORPHANED BY THE HANGMAN’S NOOSE LEARNS THE AWFUL TRUTH ABOUT HER GRUESOME CHILDHOOD’. Perrin’s colourful three-page spread was followed up two years later by a chapter in his book No Fear Nor Favour!, re-treading some of the juiciest stories that had been carried in the Bucks Free Press since it was first published in early Victorian times. In among the 16 chapters, ranging, with alliterative abandon, from ‘Of Fish, Riot, Rags and Rabies’ to ‘Of Parrots, Pubs and Punting Pleasures’, was one entitled, much more succinctly, ‘Of a Musical Milkman and Murder Most Foul’.

However, neither Perrin’s 1984 report nor his more fleshed-out follow-up in 1986 – by which time Hollie had married for the fourth and final time – came even close to telling the whole, extraordinary story of a humble dairyman of musical ambitions with, on the face of it, homicidal tendencies. I would later begin to uncover the truth in much greater detail after I decided to take a look again at that tube of press cuttings, which had been gathering dust for years in a corner of the cottage.

As if Bailey’s own background story wasn’t fascinating enough, there was his sensational murder trial, historic for being the first in Britain ever to feature women jurors. Then, throughout this tale there was a recurring, eerie suicide motif. This theme of self-destruction would extend, I’d learn, after hours of digging through the Home Office file and related papers at the National Archives, to the Judge, the hangman and the Prosecution’s most distinguished expert witness. The Musical Milkman cast a long shadow.

Perrin did, however, note perceptively that there was a singular irony in the site of Kate’s unmarked grave. For, interred just a few strides away with an altogether more lavish memorial, was one of the world’s greatest and most prolific crime writers, Edgar Wallace, who had died a dozen years after the murder.

What Perrin wouldn’t have known was that, long after he resurrected the case for mostly local consumption, Little Marlow would become a fashionable location for filming top-rated television crime shows like Inspector Morse, Miss Marple, The Inspector Lynley Mysteries and, most prolifically – on one occasion even inside Old Barn Cottage itself – the ever popular Midsomer Murders. The Musical Milkman Murder was, however, a real-life slaying that would have taxed the imagination of even the most inventive TV screenwriter.