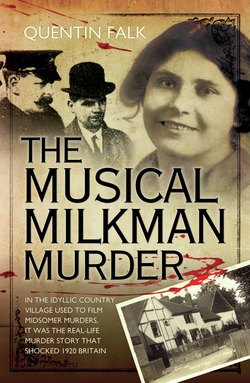

Читать книгу The Musical Milkman Murder - In the idyllic country village used to film Midsomer Murders, it was the real-life murder story that shocked 1920 Britain - Quentin Falk - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

SCENE OF THE CRIME

ОглавлениеUntil the tumultuous events of September, the only other crime that seems to have been worth reporting that year in Little Marlow was committed some months earlier when three local men were charged with stealing a chicken, worth 10s, from a farm in the north of the parish. One of the men, Jas Clark, was further charged with ‘maliciously killing a fowl’, one of two that a witness – Henry Field, son of Wood Barn Farm’s owner, George Field – actually saw him shoot in a lane alongside the family property.

After the trio made off, Henry picked up some feathers, several wads of a cartridge and the dead chicken that had been left behind, all of which were later produced in evidence at Marlow Police Court. On the afternoon of the alleged poaching, the three defendants were picked up and taken to Marlow Police Station where they were asked to account for their movements earlier that day. Clark claimed to have been at a football match, while the two other prisoners, brothers Sidney and Harry Price, said they’d been for ‘a walk round’. Their case wasn’t helped by the fact that in Sidney’s pocket they found feathers similar to the ones gathered earlier by Henry Field as well as six cartridges. In Court, Clark, who, despite having many previous convictions, continued to protest his innocence, was fined £5 and the other two men 10s each. According to a local newspaper report, ‘the money was paid’.

At least they didn’t suffer the same fate as three men elsewhere in the same county some 30 years earlier. On that occasion, Frederick Eggleton, Charles Rayner and Walter Smith – notorious poachers, all armed with guns – were confronted in the woods of a large estate at night by two zealous keepers carrying just clubs. In the resulting fracas, the keepers were both shot to death. At the end of a controversial trial where it was argued that the poachers were guilty merely of manslaughter because they were attempting to defend themselves, all three men were convicted; two, Eggleton and Rayner, were hanged for murder, while Smith received 20 years’ penal servitude after his plea of manslaughter was accepted by the jury.

Before the arrival of George Arthur Bailey, that kind of violent sensation would have seemed anathema to a community like Little Marlow, described in a contemporary Kelly’s Directory as ‘a widely scattered place, with a few farms and shops, and bounded on the south by the Thames’. Although less than 30 miles from London, it was, in the days before mass cars and motorways, the heart of the country. Almost exactly halfway between the more populous towns of Marlow and Bourne End, Little Marlow was a ‘particularly neat and select hamlet, the villas being mostly let out for the summer visitors’, according to the Maidenhead Advertiser in October 1920. Its tiny village centre in an otherwise sprawling parish was still mourning the loss of some of its finest young men, most in their twenties, who’d either died in action during the Great War, or later succumbed to their injuries back home.

Men like Charles Werrell and William Napper, both aged 20, of the Oxford & Bucks Light Infantry. Werrell, who had been working in the gardens of the Manor House at the outbreak of war, managed to join up in June 1915 by ‘making an addition to his age’. He was killed in France less than two months before the Armistice. Napper, who’d been educated at the village school and was employed by a local cycle-maker, died of his wounds in Belgium a year earlier. Percy Twitchen, from one of Little Marlow’s oldest families – there are local records of Twitchens from 1767 – fought with the Hampshire Regiment and died in Palestine aged 26. Charles Harrowing was another Oxford & Bucks Light infantryman, a corporal, son of a groom, whose final resting place was Doiran Military Cemetery in Northern Greece. He was 25.

Philip Harris, one of six children, was a year younger when he died in action on 26 May 1915 and is ‘remembered with honour’ on the Le Touret Memorial at the Pas de Calais. The exception to this 20-something roll-call was Worcestershire-born William Tolman who, before enlisting, worked in the village as a domestic chauffeur, probably at the Manor House. He was 46 when badly injured serving with the Motor Ambulance Division of the Royal Army Service Corps and died at home just after New Year, 1916.

These are just a handful of names from among a longer list of the Little Marlow fallen that are inscribed on a memorial to the war dead of the wider parish affixed to a wall on the south aisle of the village’s 12th-century church, St John the Baptist. On the first Sunday in July that year, during an afternoon service whose large congregation almost overflowed the church, that memorial, executed in statuary marble, locally designed and paid for by public subscription, was officially unveiled. The vicar, Rev John Best, read out the list of names, no fewer than 42 in all, or, more revealingly, around 4 per cent of the entire parish population.

So maybe it wasn’t hugely surprising that, when, less than three months on, the spectre of violent death through the Bailey trial suddenly encroached again on a still grief-stricken community, the effect was seemingly seismic and the subsequent events followed in occasionally hysterical fashion with, according to local newspaper reports, ‘booing and groans’ regularly accompanying Bailey’s arrivals and exits at the various hearings following his arrest.

The first of these was two days later when, at Marlow Police Court, in the briefest of proceedings, Bailey was charged with ‘feloniously killing and murdering’ Kate. He made no reply and was remanded to Oxford Prison. A large crowd had assembled outside and, as Bailey, together with two policemen, climbed into a car on his way to Oxford, his smile to the crowd was said to have turned to a flush as angry shouts rang out from women lining the pavement. Wearing a bowler hat, fawn raincoat and a stripy tie, he then covered his face with the hat until the car managed to drive off.

The following morning at 11.00am sharp, Arthur Charsley, the Coroner for South Bucks, opened the inquest into Kate’s death. The venue was The King’s Head, the bigger of the village’s two pubs, 400 years old with curved walls, beamed ceilings and less than 150 yards from Barn Cottage. In attendance was an all-male jury of 12 Marlow residents of whom Mr AE Barnard was selected to be foreman. The two senior officers in the case – Supt Kirby and Inspector West – along with PC Gray represented the police, Gray doubling up as Coroner’s Officer. Kirby and West offered brief accounts of the discovery and condition of the body and that ‘a man named George Arthur Bailey was in custody’, while Bailey’s brother-in-law, James Jennings, confirmed that the body was indeed that of his sister-in-law, adding, during the briefest of questioning, that the couple had always seemed to have been on ‘affectionate terms’ and that he knew of no reason why Bailey should have wanted to murder Kate. Bailey’s mother, Betsy, who had travelled more than 200 miles from her home at Berrynarbor in North Devon, was not required to give evidence.

Mr Charsley brought the inquest to a close, explaining that sufficient evidence had been given for him to grant an order for burial. He told the Court that he would in due course reconvene the proceedings at Marlow Police Court to make it more convenient for the jury. Examination of Kate’s stomach contents by Dr Spilsbury, the Home Office pathologist, would, he added, probably be completed in about three weeks’ time.

The next afternoon, a tiny congregation mainly comprising old Mrs Bailey, James Jennings and George Weston, a local official who’d made the arrangements, attended Kate’s funeral at St John the Baptist, conducted by Rev Best. Later that afternoon, as the light was fading fast, Kate was buried, not in the churchyard but at the cemetery about half a mile away off Fern Lane. Her final resting place, known as Plot 256, was as anonymous as most of her short, sad life.

Less than a week later, shortly before midday on 12 October, Bailey, his black hair tinged with grey and now sporting several days’ growth, was wearing the same fawn coat and bowler hat when he made a second, even shorter appearance at Marlow Police Court; again he was remanded in custody after the traditional request by Supt Kirby. The prisoner bowed towards the Magistrate, Mr Buckingham, and visibly mouthed ‘Thank you’ before being hurried out of the dock.

His journey to Marlow wasn’t, however, without incident. Changing trains at Bourne End for the branch line, known as ‘The Marlow Donkey’, the ever-smiling Bailey was greeted by a hostile crowd, again mostly women, who booed him roundly. Outside Marlow Station, just a stop away, an even larger crowd had gathered, which, like the throng around the Police Court as he climbed out of a taxi, made its aggressive feelings loudly heard. ‘Even this did not disconcert him,’ reported the Bucks Free Press, ‘and once again there was a cynical smile on his countenance.’

The return journey was no less fraught, with angry women this time actually spilling on to the platform itself at Marlow. As cameras representing local and national newspapers flashed, Bailey spotted one in particular and shouted, ‘All right, old boy,’ as he tried, unsuccessfully, to shield his face. He was quickly bundled into the train and the blinds of the carriage window were drawn down.

In an attempt to instil a little more colour into its report of the day’s short but dramatic proceedings, the Bucks Free Press included an interview with an unnamed ‘lady resident of Bourne End’ who told the paper that Bailey was very much liked in the district by his milk-round customers. ‘He was always speaking about his dear wife (the deceased woman) and was loud in his praise of her capabilities. I remember him telling me that he was run down, and was going to have a week’s rest. I expressed the hope that he would benefit by the change. He wished me “Good day!” and left my door. It was during his week’s rest and change that his poor wife was found dead.’

Another week, and yet another two-minute appearance as Bailey underwent, on 21 October, his third Oxford round trip, this time before a full strength of Marlow Magistrates and with Supt Kirby advising the Court that, following another seven days’ remand, the prisoner’s next appearance might require at least two days at Marlow with overnight stays for the accused. The brevity of the visit in no way lessened the continuing ill will, with ‘shrieking and hissing’ now added to the familiar booing of the accused. The numbers striving to access the Court would have filled the place half a dozen times over. The crush getting in provided ‘a spectacle that was unbecoming’. Meanwhile, there was still no news of a resumed inquest.

This almost frenzied local antagonism was rather neatly mirrored in another, much higher-profile case of alleged wife poisoning, which happened to coincide almost exactly with these opening salvoes against Bailey. In west Wales, 45-year-old solicitor Harold Greenwood was on trial for killing his wife Mabel, whose death in June 1919 was originally attributed to heart disease. After the funeral, rumours began in the Greenwoods’ home town of Kidwelly that her death had been far from natural, a buzz exacerbated by Greenwood remarrying just four months after Mabel’s demise.

In April 1920, her body was exhumed and the subsequent inquest recorded that she had died from acute arsenic poisoning, which had been administered by her husband. On hearing this verdict, the public present apparently broke into rapturous applause. In the event, Greenwood would, following a very skilful defence by the greatest criminal lawyer of his day, Sir Edward Marshall Hall, be acquitted, although he died a broken man just nine years later.

The ‘phoney war’ of the preliminary hearings finally gave way to the tooth-and-claw of a full-scale, pre-trial inquiry into the case against Bailey which, from its outset on 28 October, prompted garish local headlines like ‘SENSATIONAL EVIDENCE’, ‘PRISONER’S DRAMATIC OUTBURST’ and ‘LARGE CROWDS BESIEGE THE COURT HOUSE’.

According to FJ Sims, the Assistant Public Prosecutor, the story given to the Magistrates would be ‘one of the most remarkable ever heard in a Court of Justice’. The first ‘sensation’ came quite early on the first day of a three-day hearing, with the introduction of a letter that had been discovered soon after Bailey’s arrest ‘addressed to the Coroner via the Police’. This would be the first of a number of strange, rambling, seemingly suicidal yet oddly compelling documents composed by Bailey that would come under the public gaze over the next few months. It read:

Please do not worry my people. There is no need to divulge where I come from, or divulge that I belong to so and so. For my dead mother’s [very odd this for, as we will discover, his mother is actually very much alive if not terribly well] and brothers’ and sisters’ sake. There is no need to call any witnesses for evidence. This is the first act [Bailey pointed out on Day Two that this should have read ‘the final act’ but had been copied out wrongly] of an unbalanced yet vigorous brain. My darling is waiting for me. I gave her hers first; then I follow, the same death that she died. I handed the poison to her, she believed my statements. They are our secret. I pray God that he lets us be united as we have always believed we should be. She is asking for me. For her child now. I have contemplated horrible things – almost accomplished them. Please take great care of the music I leave behind. It is the notation of the future. If the old school would only overcome their jealousy, their conservatism and prejudice. I have shown several young ladies its simplicity. Miss Field, Miss Edwards, Miss Marks can explain more.

I heard my darling die on Wednesday 29th Sept, 7.15pm. I have waited my fate and now I meet it. My own dear wife knows and knew but she is so brave, so staunch. Please that God will forgive her. Forgive me. Please do not let this tragedy destroy the future of this notation but that someone with foresight will take it up. I ask no pardon from the world. I have ever been a source of worry and trouble. It has been harder to fight than I can resist and I have tried. But I know and knew that it must all end in some such way.

I should like our three bodies laid together. That is why I came back to take one last look. Give one last kiss to my beloved. I gave her stramonia first, then hydrocyanic. No blame attaches to the chemist. I always could bluff to attain my ends. Goodbye poor dear mother and my own dear sister Nellie and brother-in-law Jim. Wayward when young but easily to be corrected, if they had only known. I believe I have been broken-hearted since poor dad died and I failed to make good, but my own beloved wife Kitty understood me and loved me so much and I, yes in my own way my life has been given to her, no matter what I intended to do. It was always decided to go together and not to leave our baby behind. Please God, Father of all nature, forgive us all. But I do not believe in thy existence – as more simple than the Bible? Is tonight just our father who must recognise him as such.

My darling I am coming [written upside down]

The new music upstairs that will be found with our belongings is the system of the future. That this tragedy has followed within so short a period.

Wearing his perma-smile and now allowed to sit in the dock while taking copious notes, Bailey was charged not only with capital murder but also with a serious sexual offence against Miss Marks, one of the three above-mentioned young women who had answered his newspaper ads. Without legal representation at this stage, he also occasionally asked questions of the various witnesses, mostly to try to establish that he and Kate had been on very happy terms. However, in the case of Miss Marks who, under Mr Sims’ careful probing, gave a very full and distressing account of her night at Barn Cottage while Kate lay dead in the next room, Bailey restricted himself to just one question: ‘You allege that these serious happenings occurred?’ To which she replied simply, ‘Yes.’

Since most of the same witnesses’ testimony before the Magistrates and, later, the inquest will be more carefully examined in due course when it comes to the actual coverage of Bailey’s trial, here it is perhaps sufficient occasionally to note some of the prisoner’s own cross-examination of them in the course of the two hearings. The latter was strung out because of adjournments across two months, before Bailey would later get the benefit of Counsel at the Assizes.

Mr Sims was just about to get Day Two under way by calling more witnesses when Bailey – who seemed to have acquired an appetite for advocacy on Day One – stepped in with: ‘I am sorry, your Worships, to interrupt the proceedings of the Court, but I would like to ask you to grant me legal aid …’ to which Mr Shone, the Magistrates’ Clerk, replied, ‘The Court has no power to grant a certificate of legal aid; they can only do so when the nature of the defence is disclosed.’

The Chairman, Mr Morgan, added, ‘We must refuse it. You can make your application when you are before a Judge, if you are committed for trial.’

Bailey retorted, ‘I have several witnesses to call. Then their evidence will be placed on the depositions.’

Mr Morgan reassured him, ‘You shall have every opportunity to call whom you wish.’

The revelation of the Coroner’s letter the previous day was almost matched this morning by the disclosure of another of Bailey’s colourful statements, this time given verbally and, according to PC John Gray who was in charge of the prisoner at Marlow Police Station after his arrest, entirely unsolicited. Reading from his notes, PC Gray told the Court that Bailey had confided to him:

‘Between me and you, me and Kit [Kate] were in the garden on Wednesday evening, and then almost 5.00pm we went indoors and had tea, some buns and bread and butter. Her last words to me were, “You will have to come, too.” We were very loving to one another. I had already made up my mind what to do; but although I am an atheist, it came across my mind that we should be parted for ever. On Thursday evening, I locked the front door, took the child, and put the key through the letterbox and went off. My intentions were to come back to Little Marlow on Saturday. I done wrong in telling them at Swindon that my wife was at Wycombe Hospital. It has made it look black against me. I should have made a clear statement to Inspector West, but as it will not help the Court proceedings, I shall keep quiet. If this goes against me, I wish all my things at Barn Cottage shall be burnt, except the push chair, and I want that to be given to my little girl.’

‘If I remember rightly, about “her last words”,’ Bailey asked PC Gray, ‘I think I stated “We were often talking about these things”?’

‘No,’ replied the police officer confidently.

‘You had a lot to remember; perhaps you cannot recollect,’ Bailey noted, with a hint of sarcasm worthy of a more experienced advocate.

He also took his brother-in-law to task after Jim Jennings told Mr Sims that Bailey had ‘a dirty smile’ on his face when he told him and his sister Helen that he’d be returning to Little Marlow after reporting that Kate had died.

‘You said that I had a “dirty smile” on my face? Give us a clearer explanation of what you mean?’

‘It was not a clear smile.’

‘Malicious or evil?’

‘I could not say that.’

Then followed the curious sight of brother cross-examining sister as Bailey questioned Helen Jennings on the matter of his music.

‘We used to come to you in all our troubles and trials?’

‘Yes, you did.’

‘Was I not agitated about a system of music that had been published and did I not write off for a copy?’

‘Yes.’

‘Did I not mention to you that my ideas had been stolen?’

‘You did.’

‘I sent off for a copy, and when I received it, did I not say, “Thank God, it is not mine”?’

‘Yes.’

‘And was I not much relieved?’

‘Yes.’

The Bucks Free Press noted that Bailey was ‘moved to tears’ for the first time while Helen was giving evidence. It also observed that Bailey’s mother was present in Court, cutting ‘a pathetic figure, her face buried in her hands’.

The matter of the accused’s music came into much sharper focus with the evidence of Marlow-based musicologist Dr Samuel Bath; not in a good way, though. He said he had examined examples of the notation as shown by two of Bailey’s ‘students’, Miss Marks and Miss Field, and found them to be ‘grossly grotesque’. To much laughter from the Court, he likened one of them to ‘a crude drawing of a trail of tadpoles seeking an incubator’. He added that he thought its value was nil and anyone trying to learn it, if they could, which he doubted, would be no better off.

After this, Bailey was naturally anxious for some kind of comeback.

‘Do you understand that it is a new staff system?’

‘I do not admit it is a new system.’

‘Have you had no opportunity of being initiated into the simplicity of this new system?’

‘No.’

‘That is all I have to ask,’ concluded Bailey, probably realising he was on a hiding to nothing with Dr Bath.

But it didn’t quite end there, with Mr Sims asking the witness, ‘Would you be able to play this system on the piano?’

‘No. I should hardly know which way to begin it,’ Dr Bath replied unswervingly, provoking more gales of laughter.

This time, Bailey’s retort smacked of desperation. ‘There are other scripts in the possession of the police that explain this system of music.’

The prisoner’s lot took another unhappy turn straight after Dr Bath had given evidence with the arrival next in the witness box of one William Geo Day, described as a ‘valet of 14, Princes Gardens, London’. Day, who said his home was in Bourne End where he was living with his mother at the time, told the Court that on 15 September he’d been riding his bike back from Marlow during the evening and encountered Bailey and his wife about 50 yards from Barn Cottage. He alleged that he saw the prisoner with his right arm around Kate’s throat and left arm about her waist, and that he heard Bailey tell her, ‘My God, I will put an end to you.’ He cycled on and the next day returned to London where, a little over a fortnight later, after being prompted by the butler, he saw pictures of Bailey in the Daily Mirror and the Daily Graphic. At that, he got in touch straight away with Supt Kirby and with his local police in Chelsea.

‘Whereabouts did this alleged episode take place?’ Bailey asked Day.

‘About 30 yards down the lane.’

‘Was it in an open field?’

‘No … on the roadway.’

‘How was she dressed?’

‘I have an idea she was dressed in a check costume.’

‘I have no more questions to ask, your Worships.’

Following this unsatisfactory exchange – for Bailey, at least – Mr Sims asked for a further remand until the following Monday when he would call all the various medical witnesses. Mr Morgan told Bailey that he should prepare his own list of witnesses giving an idea of their evidence so the Magistrates could then decide whether it was relevant or not. Before being taken back to Oxford, Bailey said that he hoped the police could be influenced to allow him a clean collar and shirt as well as a decent shave before the resumption after the weekend.

When he reappeared 48 hours later in the dock at Marlow, it was obvious from his still somewhat dishevelled appearance that he hadn’t been granted any of the above. The medical experts, including the Home Office pathologist, Dr Bernard Spilsbury, and official analyst John Webster, who only weeks earlier had been together on duty at the Kidwelly case in Carmarthen, duly gave their evidence. At its conclusion, Mr Sims told the Court that that was the case for the Prosecution. Then the Chairman explained to Bailey that he was now allowed to give evidence and call witnesses, in that specific order.

Bailey stood up in the dock and said:

‘Your Worships, I beg to emphatically deny both charges laid against me. I hope to prove that my purpose in obtaining these various drugs and sundries was for the purpose of taking up farrier work – not as a qualified veterinary surgeon – for the purpose of raising money. That the cyanide of potassium was ordered for the purposes stated to Miss Parsons [a photographer’s assistant with whom the Baileys had shared accommodation at Millbrook and from whom George had hoped to obtain poison in order, he claimed, to destroy wasps’ nests]. I hope to prove that my system of staff notation is all that I claim for it, and not a grotesque absurdity; that it was not a farce, or a cloak for nefarious designs, but the fruits of hard study and investigation. That I did not commit a felonious assault or attempted rape on the person of Miss Marks. That I did not threaten to assault my wife at Little Marlow; we were not there; that evidence is utterly false. That in the main, the evidence of the Prosecution is built up on unreliable facts and supposition. That I acted and thought throughout the whole period, from my coming to Millbrook, to the taking of and the living at Barn Cottage in an abnormal [sic] manner, under great stress of mind, I agree. That this remarkable case is just a simple story of love and devotion on both sides; hardships; trials surmounted; triumph within sight; then disaster and collapse. So I reserve my defence and desire to plead legal aid to assist me in my defence.’

The Chairman told Bailey that he would be committed for trial at the Bucks Assizes on both the capital charge and for attempted indecent assault. However, Mr Morgan added, ‘We cannot grant you a certificate for legal aid, but Mr Shone [the Clerk] will send all particulars of your case to the Home Secretary.’ He then congratulated the police for their efforts, noting Supt Kirby and Inspector West, ‘who had very slender evidence on which to work, and which resulted in a very clever arrest of the accused man’.

The following day, many of the same faces, including Bailey who’d asked to attend, were reassembled back at Marlow Police Court for a resumption of the much-adjourned inquest. They also numbered among them the London-based valet Mr Day who had, on Day Two before the Magistrates, delivered his bombshell suggesting that a fortnight before Kate died, he’d actually witnessed physical and verbal violence involving the prisoner and his late wife. He repeated his assertion before the Coroner and jury.

One of the jury asked him, ‘Did you not interfere when the man made that remark?’

‘Not at all … simply a case of man and wife.’

‘And you did not inform the police?’

‘No.’

Bailey asked, ‘In which direction was my wife’s face?’

‘Marlow.’

‘At 9.30 at night, you recognised us on a dark night?’

‘It was not dark.’ [It was in fact summertime.]

‘What clothes was my wife wearing?’

‘A plaid dress.’

‘You said the other day she was wearing a check?’

‘I wish to withdraw that word and substitute “plaid”.’

‘A very good witness.’

‘I have since picked out the clothes from others shown me, and those produced are what Mrs Bailey was wearing on the evening in question.’

‘At 9.30 on a dark night you say you recognised us?’

‘Yes.’

‘How tall was my wife?’

‘I should say 5ft 6in or 5ft 7in.’

‘Would you be surprised to learn that her height was 4ft 11in to 5ft?’

‘I will not pledge myself as to the height.’

Much of the day’s other evidence was simply a reprise of what had been heard before in another Court. However, shortly before the inquest was again adjourned, hopefully to resume the following Tuesday, Bailey’s cross-examination featured once more after PC Poole and DS Purdy had furnished official details of Bailey’s arrest in Reading.

‘What state of mind did I appear to be in when you arrested me?’

‘You appeared to be dazed at the time.’

‘And yet I kept on making gruesome jokes?’ [There is, sadly, no record of what these ‘gruesome jokes’ might have been.]

‘Yes.’

In the event, all involved would have to endure yet another delay – it seems Mr Webster, the Home Office analyst, was caught up in a case at Maidstone, so the Coroner announced that, availability of experts permitting, the inquest would now be finally sorted on 26 November.

On this particular Friday, Bailey’s arrival at Marlow was, for a change, almost low-key with the crowd, unaware of when he was actually due, smaller and less vociferous than before. Onlookers would, though, have noticed a change in his physical presence with now, the Bucks Free Press reported, ‘streaks of grey in his otherwise black hair being very pronounced’.

Dr Spilsbury confirmed that death was due to poisoning by prussic acid and would have occurred any time between five minutes and half an hour of its administration.

After the various doctors had completed their evidence, Supt Kirby returned to the witness box and gave details of a discovery he and Inspector West had made during a comprehensive search of the bedrooms three days after Kate’s body had been discovered. In a chest of drawers, they’d found a small box in which, among a number of photos and picture postcards, was a small book in which was written what appeared to be a letter that was neither dated nor signed. It opened: ‘Mother, will you take care of little Hollie for me, or see she is taken care of: I can’t stand it any longer …’ and rambled a little in a rather self-pitying way about how difficult things were to bear. It ended with: ‘God knows I have had it all taken out of me: the shame, the disgrace of it all … I can’t always forget, if George can.’

After Mr Charsley finished reading out what seemed to be just the latest in a series of incendiary documents revealed during the course of the various pre-trial hearings, he asked Supt Kirby if he knew in whose handwriting was this distressing note.

‘No, sir,’ replied the doughty senior police officer from High Wycombe.

The Coroner then addressed the jury, summarising the case against Bailey and reminding them of some of Bailey’s letters and statements including an exchange with PC Poole after he’d been taken to Reading Police Station following his arrest. ‘Do not say anything to the people at Swindon about this. Between you and I, I might have had something else inside me, but you were a bit too fly for me.’ When PC Poole later gave Bailey a blanket, the prisoner had remarked, ‘I suppose I shall be colder later on.’

Mr Charsley told the jury that they must consider three questions: did Kate die from prussic acid or hydrocyanic acid poisoning? Was that poison administered to her, taken voluntarily by her, or was it taken by accident? And if they thought it was given to her, would they say who gave it to her? If the accused gave her the poison, then he must be found guilty of wilful murder.

Before the Court was cleared for the jury to consider their verdict, Bailey protested about Day’s evidence, especially its inconsistency. The Coroner ruled that the jury could discard the evidence of Day from their minds, to which several of them piped up, ‘We have already decided to do that.’

Mr Charsley asked the prisoner if he had anything further to say. ‘No,’ he replied, ‘Mr RS Wood of High Wycombe and Thame is undertaking my defence,’ referring to the senior partner in a firm of highly respected local solicitors.

It took the jury just 15 minutes to conclude that Kate was poisoned and that Bailey was responsible. The Coroner intoned the inevitable: ‘George Arthur Bailey, it is my duty to commit you to the next Bucks Assizes on the charge of wilfully murdering your wife.’

The prisoner bowed, smiled – yes, that smile – and left the dock followed by a pair of warders. Before leaving Court for the return journey to Oxford Prison, Bailey called out to the representative of the Bucks Free Press, saying, ‘If I do not see you at the Bucks Assizes, will you please see my sister and ask her what took place on the Tuesday before my wife died?’

‘Do you mean Mrs Jennings?’ came the reply.

‘Yes,’ said Bailey, ‘You ask her … it will astound you.’

And with that, the legal preliminaries in the case of R v Bailey were finally completed ahead of the trial at Aylesbury which was likely to be quite soon after the turn of a new year. In less than two months, it wouldn’t only be Bailey who would be facing an ordeal but also several of the young women who had fatefully answered his advertisements and would have to give evidence in a much wider glare of publicity.

For three older women from the Aylesbury area, however, there would be a different kind of test altogether at the Bucks Assizes, one that would make legal history.

Meanwhile, the local paper reported that, having completed all their analysis, the police had handed back Barn Cottage to the owner Mrs Boney and that it had been re-let.