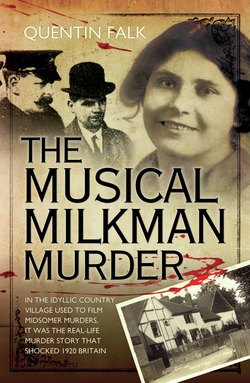

Читать книгу The Musical Milkman Murder - In the idyllic country village used to film Midsomer Murders, it was the real-life murder story that shocked 1920 Britain - Quentin Falk - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

MURDER MOST FOUL

ОглавлениеThe year 1920 was a very good year for murder and murderers. A seven-year high of 313 ‘homicides’ – the official Home Office catch-all term for murder, manslaughter and infanticide – was reported that year in the UK. It was a figure that, apart from another brief peak in 1925, would remain unsurpassed until the depth of the Depression in the early 1930s.

Less than two years after the November Armistice, as the country was still painfully trying to come to terms with the legalised slaughter of the Great War, in which two-and-a-half million Britons had either been killed or wounded, and the subsequent onset of a catastrophic ’flu epidemic that would claim millions more, ‘foul play’ came in many and all kinds of heinous guises.

In January 1920, farm labourer Edward Burrows, a convicted bigamist, took his mistress Hannah Calladine and their year-old son out on to the moors near Glossop in Derbyshire, murdered them and threw the bodies down the air-shaft of a disused mine. The next day he returned, this time disposing of Hannah’s four-year-old daughter in the same place.

In August, the body of 17-year-old typist Irene Munroe was found buried in the shingle at the Crumbles near Eastbourne. It transpired that Munroe, on holiday at the coast, had been savagely beaten to death by Jack Alfred Field and William Thomas Gray, a pair of ex-Servicemen in their twenties, after she tried to resist their sexual advances.

A month before that, at Hay-on-Wye, the sleepy heart of Welsh border country, Herbert Rowse Armstrong, a diminutive, small-town solicitor and retired British Army major, poisoned his hen-pecking wife Katharine to an agonising death by arsenic.

All four killers were eventually caught, tried and hanged.

Then, on 17 September 1920, 32-year-old dairyman George Arthur Bailey, his heavily pregnant wife Kate – ten years his junior – and their two-year-old daughter Hollie, moved into Barn Cottage, Little Marlow, about half a mile up from the Thames in South Bucks, after paying in advance a month’s rent of £6.

Just over a fortnight later, on 2 October, Kate was found dead by police, her body wrapped in a sheet beneath a camp bed that had been draped with a large counterpane in an upstairs bedroom of the quaint Elizabethan cottage, which had once been a thriving village bakery. From the discoloured state of the corpse, clad in a nightdress and woollen undergarments, it was evident she had been dead a few days. There was no sign of Bailey or the child.

Five months earlier, towards the end of May, Edwin Hall, who ran a dairy in Bourne End (a small town also bordering the Thames, about a mile-and-a-half east of Little Marlow), placed an advertisement in the Farmer and Stockbreeder for a milk roundsman. Soon after he received a telegram from a George Bailey indicating he was ‘suited’ to the job. Hall then telegraphed Bailey at the address in Swindon requesting more information and, less than a week later, received the following letter, dated 27 May:

I have pleasure in stating that I have the qualification as in advertisement. I am abstemious, steady, energetic, of decent appearance, also a thorough milker, if required … Married, one child, with a life’s experience in the dairy trade, retail and producing. I am desirous of finding a good situation, one that will be permanent for years, everything being satisfactory. My experience covers Devon and Cornish resorts, provincial towns and London … Respecting the wages required, sir, that, I think, is best left to you, as so much depends on local conditions now, with which you are more familiar than I am, and as to whether you pay an inclusive wage for honest, persevering work, or on a commission basis for new trade. I think the money question, sir, can be safely left for mutual settlement as far as I am concerned. I am free to take up my duties at any time, sir, or to come and see you, and you may depend on my efforts to further your business and to endeavour to give you complete satisfaction. Trusting to hear favourably from you, I am, sir, yours faithfully, GA Bailey.

They met up a couple of days later in Wallingford, about halfway between Swindon and Bourne End, and Hall was so impressed with Bailey that he hired him right away at £3 a week with the promise of commission.

Just after Whitsun, on 2 June, Bailey left his sister Helen and her husband Jim Jennings’ house in Swindon where he’d been living with Kate and Hollie, and moved into a small, two-storey, semi-detached house called ‘Millbrook’ in Bourne End, owned by Miss Mary Hillary, who lived nearby. The plan was for Kate and Hollie to remain in Wiltshire until Bailey had found his feet in Buckinghamshire.

At first, he lived in Millbrook with two or three other lodgers before, in July, writing to ask if he could rent the whole place furnished because he now wanted Kate and Hollie to join him. Also, would Miss Hillary object, he wrote, if they shared with another couple called Roper who had two children? She would say later she was surprised by this as she thought he had wanted to live there alone for a while, the arrangement being that he’d have it for at least three months before deciding whether to take it for longer.

It seems that he was an instant success after taking over a round – consisting of some 300 customers in Bourne End and adjoining Wooburn Green – that Hall would admit later was quite ‘difficult’. About six hours in duration, Bailey started at 6.30 in the morning and finished around 12.30pm, after which he’d have to clean the churns and various utensils in the dairy. Boosting milk sales as well as those of butter and eggs, the persuasive Bailey was soon on an extra 5s a week with the promise from Hall that he might well get another rise in three months’ time. A short, stocky man with dark hair, Bailey, who quickly became popular with his customers, could often be heard whistling or humming while doing his round, with the result that he soon earned the nickname, ‘the Musical Milkman’, or, just occasionally, ‘The Whistling Milkman’.

What those customers didn’t know at the time was that Bailey had, he would proclaim, authentic music ambitions, which were first revealed, albeit cryptically, in an advertisement he placed in the Bucks Free Press on 25 June. It read:

Young Lady, refined, educated, musical ability essential, required to help originator copy manuscript proof sheets and assist in development of propaganda. Pleasant, unique work; light hours. Salary, Five Guineas weekly to right person – Write, G.A.B. Free Press Office, Wycombe.

He believed he had invented a new system of musical notation that would, he hoped, simplify the teaching and the playing of music which would then prove, eventually, not only remunerative to pupils, and possibly aspiring concert pianists, but also, of course, to him.

The ad attracted a number of applicants from Marlow, Bourne End and High Wycombe, as did a follow-up two months later in the same paper. That second ad was, to say the least, rather more graphic, not to say distinctly more suspect in its content:

Young ladies, not under 16, must be over 5ft 6in, well-built, full figure or slim build. Applicants below height specified, please state qualifications as to appearance, etc. Required for highly specialised work, indoors or out. Applications from all classes entertained, as duties will be taught. – Write, in first instance, to “Snap”, Free Press Office, Wycombe.

The applicants – young ladies in their late teens or very early twenties – like Winifred Field, Gladys Edwards, Lilian Marks, Mabel Tubb, Ethel Rouse and Violet Baker – flocked to Millbrook during August and early September to be given the once-over by Bailey and, in certain cases, promises of paid work that might require occasional sleepovers. The mothers of Ethel and Violet decided they needed to check out Bailey for themselves and came to Bourne End for a meeting. Mrs Rouse wanted to know why he was going to provide her daughter with a costume. He told her that, as he planned to have 40 girls working for him, he wanted them to be alike and look smart to advertise his music. She expressed her concern to him that these would be young women in his care and that she didn’t want anything to happen that might blight their young lives. He assured her, ‘There are some very funny things happening nowadays, but it will be quite all right.’

This human traffic to Millbrook was noted at the time by the local Bourne End bobby, PC John Gray, who would later say that after being given official instructions to keep a watch on the house – presumably the advertisements had become rather notorious locally and Bailey was, after all, an increasingly well-known character in the district – he saw as many as 30 different young women visit the place, usually between 5.00 and 8.00 in the evening.

However, there was soon a major glitch in Bailey’s living arrangements and potential base for his future musical operations. On 22 July, by which time Kate, a tiny, timid-looking woman, and Hollie had joined Bailey at Millbrook, Miss Hillary wrote to him saying she wasn’t willing to let the house to him any longer than the stipulated time – three months. In fact, she added, she’d like his tenancy to terminate sooner than that if possible; this similarly extended to Mr and Mrs Roper, as she’d been totally unaware of Bailey’s intention to sub-let to them.

When she and Bailey met two days earlier, he had complained about the rent. This galled Miss Hillary who, in her letter wrote: ‘As to the “exorbitant price” you are paying for the use of the house and furniture, it was entirely your own fault for agreeing to pay it, if you thought so, and very unnecessary to throw it in my face as you did on Tuesday. It will be none too much to make up for wear and tear of two families and three children, an arrangement I strongly disapprove of, and would never have agreed to for any consideration whatsoever.’

Effectively on notice to leave Millbrook as soon as possible, Bailey was now having to juggle his job and the replies to his ads as well as trying to find suitable new accommodation nearby where he could move his family, continue as a local milk roundsman and pursue the notation. Towards the end of August, he spotted an advertisement in the Bucks Free Press describing a Barn Cottage available to let in Church Road, Little Marlow, at 30 shillings a week, furnished throughout, complete with piano.

The ad had been placed in the paper by Miss Alice Boney on behalf of her mother, Charlotte Boney, with whom she lived in Hove, Brighton. Mrs Boney had bought the cottage in 1917 for £410 when it was one of the tied properties being sold off that year by the Bradish-Ellames family, owners of the village’s Manor House and much surrounding land and housing.

Curiously, the name ‘Barn Cottage’ doesn’t actually figure in the official cottage deeds, which make reference instead to ‘The Old Bakery’. That was, for years, the prime use of the building up until around 1915. The name, referring to the large barn that ran east to west along the north side of the property, seems more likely to have been unofficially adopted for general use by both the new owner and, subsequently, in the press coverage of the case.

It was certainly in this guise that the Maidenhead Advertiser, which regularly covered Little Marlow district news, offered around the time of the crime the following, and extremely alluring, description of the property, more worthy of an estate agent’s blurb than a résumé for the site of a slaying:

A more artistic, rustic cottage could not be imagined – old, plainly built and rambling, but a veritable picture for a country house. The main part, with gabled roof, clothed in Virginia creeper, the living portion forming the second section, the quaint bent window, the rustic lintel and door-posts with a horseshoe nailed to the door, the barn with the high roof standing next to the living portion, and from which the cottage takes its name, form as a group a most handsome rural residence. It has of late been owned by some ladies [sic], who let it for the summer season, and it is stylishly furnished. There is said to be eleven rooms, but beyond the hall and the chief rooms downstairs, the rest are small rooms. There is a garden on the north side with fruit trees, wire-baskets, water butt, and other country accessories. In the front is an old-fashioned garden, with just one solitary rose on the solitary rose bush. In every way a luxurious little country ‘nest’. It had been occupied by summer visitors all the season.

The paper then went on to speculate mischievously as to how a man of Bailey’s means could afford such a place.

In the meantime, on 16 September, Bailey had met up with Miss Boney and she showed him round the place. She let him play the piano and he remarked that it needed tuning. She agreed and suggested he arrange it. He and his family moved in the next day.

A week later, Bailey jotted a letter to her explaining he’d contacted a piano tuner who’d done his stuff successfully – and would be sending her an account. He then wrote, ‘I should like to ask you whether you are disposed to sell this property as it is. I should be willing to pay £550 as it is at present. Can also put you on to a good thing in my possession …’ (was Bailey trying to interest her in his musical system?) ‘… but I want no bother through agents. I should esteem a reply, but I shall be engaged until the end of the week ending 9th of October, if you would like an interview. I am faithfully yours, GA Bailey.’

Bailey’s obvious pleasure in Barn Cottage and its future possibilities contrasted rather sharply with an acrimonious end to his let of Millbrook. A few days before he made his offer to buy, he received a letter from Miss Hillary complaining that his final rent payment was 10s short and that if he didn’t pay up ‘within a few days’ she would place the matter in the hands of a solicitor ‘and claim another week’s rent in lieu of notice, as you had no right to leave the house in the way you did without letting me know in time to take it over when you left. Please return broken wire mat missing from coal shed, which I saw at the door when I called to see you on Saturday.’

His immediate reply was short and slightly sinister: ‘Miss M Hillary, I should advise you not to try bluff, it may lead to unpleasant consequences to yourself. P.S. On receipt of name and address of your solicitor I shall be only too pleased to hand them on to firm acting for me.’

On or around the time Bailey moved into Barn Cottage, he began increasingly to take time off from his milk round because of illness. Kate went to the dairy in Bourne End on 27 September to pick up her husband’s wage packet. That same day, Edwin Hall received the following letter from Bailey:

I have been impressed by your generosity re paying me a full week’s money while I have been on the sick list, a thing I did not expect, or would not have asked for it, but at the same time I have come to work when I should not have done so, because I understood how you were placed with Mr Thorne [another roundsman] away. It is unfortunate, but unavoidable, and the first time I have been compelled to give in. I have visited the doctor again this afternoon, and it is at my own risk that I come to work until the plasters are off (lungs). It goes against the grain for me to lay up idle, also it is useless for me to come one day and lay up the next, aggravating the malady, which with short and proper treatment will enable me to resume work in a proper manner, also a satisfactory manner, which has been far from the case from my point of view on the few days that I have turned up, and hardly able to grasp what I am doing.

Four days later, Mr Hall received a further letter from Bailey, dated 29 September: ‘I shall be prepared to take up duties on Saturday [2 October]. Your obedient servant, GA Bailey.’ He never returned.

On the day Bailey wrote his second letter to Mr Hall, two of his pupils, Miss Edwards and Miss Field, arrived at Barn Cottage around 10.30am, followed soon after by Miss Marks, and they all worked together on the musical notation. The session finished at 12.30pm when Miss Marks was told she was to stay the night and to be relieved the next day by Miss Edwards and Miss Field. Miss Marks, who had given up a 30-bob-a-week job in a grocery shop to work on the notation, was then given 4s for lunch and told by Bailey to return at 7.00pm. During the afternoon, Eliza Hester and Helen Hester, who lived next door at the Post Office-cum-village stores, separately saw and spoke to Kate who seemed happy and cheerful. They never saw either her or Hollie again after that.

What actually, or allegedly, then occurred at Barn Cottage between the final sighting of Kate sometime before 4.00pm on Wednesday, 29 September and the discovery of her body three days later would begin properly to unfold later in evidence at the various hearings. What is beyond dispute is that, the following morning, after Miss Marks left the property, having, she would subsequently claim, endured a night of terror, Bailey was visited by a local clergyman, Reverend Allen, to whom she had complained that morning about the milkman’s conduct.

The same complaint soon reached the ears of Inspector William West, based at Marlow, who immediately contacted Supt George Kirby at High Wycombe. As a result, Supt Kirby then spoke to Miss Marks’ father, Reuben, about his daughter’s allegations. The next morning, 1 October, Inspector West decided to visit Barn Cottage under his own steam but found the place ‘all shut up’. He contacted Supt Kirby again and they agreed to meet up the next day in Little Marlow to see if the matter needed to be taken further. At around 9.00am, they banged on the front door, which seemed to be fastened from the inside, but got no response. Several windows were, however, open and the two police officers managed to climb into the house through one of them.

The ground floor consisted, principally, of the hall, a sitting room, the old bakery area, kitchen and parlour, or dining room, in which they discovered tea laid out on the table – a plate of bread and butter, some cake, buns, two dishes of jam and what looked, they thought, like a milk pudding. There was nothing downstairs to arouse their suspicions any further. So they decided to go upstairs and take a closer look at the bedrooms.

Two of the four bedrooms led directly off the landing. In the first bedroom, on the right of the landing at the top of the stairs, they found some men’s clothing lying on the floor. In the next bedroom, on the left of the stairs, the bedclothes were much disarranged. They then passed through the third – the ‘master’ bedroom, which overlooked the road outside and the cricket field opposite – which was only accessible via a door in the second room; then, finally, into the fourth, a back bedroom, which led off the main room.

There, they saw two single bedsteads – one, a camp bed neatly covered over with a counterpane. They pulled it back and, underneath the bed, wrapped in a sheet, was a body, which they immediately assumed to be Kate. She was lying on her back with her head facing towards a window that looked out on the yard at the back of the cottage. Surmising that she’d been dead for a while, several hours at least, the officers covered her face and left the house before stopping off, first, to have a quick word next door with Mr Hester who ran the Post Office and village stores.

While Supt Kirby began urgently to get ‘enquiries’ under way, Inspector West went to Marlow to try to find a doctor who could come as quickly as possible to examine the corpse. As luck would have it, he spotted one of the town’s GPs, Dr Francis Wills, in the High Street deep in conversation with another local medic, Dr Dunbar Dickson. They agreed to go together immediately to Barn Cottage.

Their preliminary examination indicated that the body was of a woman ‘about 25 years in age; rigor mortis has set in, more in the legs than the arms; her face was discoloured, a blue purplish colour; around the mouth there was a red-stained mucous which also covered the right eye cavity’. The neck was turning to green over the shoulder blade; the right hand was clenched and the left hand was outstretched. They removed Kate’s clothing and found that her breasts were well developed and abdomen well extended. When they turned the body over, her back was stained red and a red corrosive liquid issued from her mouth. There were, however, no obvious marks of violence, such as bruises or scratches, nothing outwardly to account for death. However, Dr Wills did (although Dr Dickson would say later he didn’t) detect an almond-like odour. In their opinion, she had been dead three to four days, and a proper post-mortem examination would be necessary.

Of Bailey and little Hollie, there was still no sign. Not for long, though. On Saturday evening, PC Henry Poole, from Marlow Police Station, was instructed by his superiors to go to Reading, where, at around 7.45pm, he met up at the railway station with Detective Sergeant Oliver Purdy of the Borough Police. Barely three-quarters-of-an-hour later, at 8.30pm, they spotted Bailey standing alone under a street lamp close to the railway station. The policemen approached him from behind before grabbing his arms. DS Purdy asked him if his name was Bailey, to which he replied, ‘No.’ He then asked him if he knew his Marlow colleague, to which Bailey also responded in the negative – which was odd since Bailey and Poole had talked in Marlow just a week earlier when Bailey was in town with Kate.

With that, they manhandled him to the police station, where he was searched. They found a bottle containing some prussic acid in his possession, and another containing opium as well as the copy of a telegram sent to Miss Field, requesting her to come to Barn Cottage on Sunday not Saturday ‘as death had occurred’, together with a letter addressed to the Coroner. Bailey also told them that Hollie was safe, staying with his sister and her husband in Swindon and that ‘she must stay there; I do not want to see her again’. Purdy then told Bailey, who had been stripped and given a blanket to keep himself warm, that he was to be arrested for murder and would be kept at Reading until handed over to the Marlow Police.

The Daily Mail reported, triumphantly: ‘The arrest was effected without the aid of Scotland Yard and it is said that use of motorcycles was responsible for the speedy capture.’

Shortly after Bailey was taken into custody, Inspector West arrived in Reading and explained to the prisoner how he and Supt Kirby had entered Barn Cottage earlier that day and found Kate, after which the doctors had been called in to examine her. ‘It is now my duty,’ he announced formally, ‘to charge you with killing and murdering your wife on or about 29 September.’ He asked the prisoner if he understood the charge against him to which Bailey answered, ‘Yes.’ He then officially cautioned Bailey, who replied calmly, ‘I don’t think I have anything to say. Let’s get back to Marlow as quick as we can,’ which they did, later that same night.

The following morning, on the Sunday, Inspector West and Supt Kirby met up again and made a further search of Barn Cottage. This time round, they unearthed quite a sizeable trawl of significant items. In a small wooden box, they discovered some bottles; among them one containing extract of ergot, a packet of perchlorate of mercury and an empty phial marked ‘Devatol. Reg A’. In addition, there was an eggcup, a small glass, a tin of adhesive plaster and a packet of cotton wool. There were also two other small boxes, with bottles containing tincture of iodine, hydrogen peroxide and Freeman’s chlorodyne; on another bottle of iodine was marked ‘Poison, not to be taken’; then there was a packet of chloral hydrate and a small swab.

On the copper (a large kitchen utensil) they found a tin of sulphur, a packet of Glauber’s salts (used as a laxative), a box of zinc ointment and a tin box containing packets of aloes and senna. There was a piece of paper, the draft of an order to the chemist, on which was written the names of various drugs. In the kitchen and on the dresser they found a bottle containing a pink fluid of what looked like lemonade. In the coal scuttle was part of a book relating to instructions for the use of Devatol.

In a bureau were a number of letters from applicants to Bailey’s newspaper ads including one from Miss Tubb, which had scrawled at the bottom in Bailey’s handwriting, ‘a very good figure’. They also found some sealing wax, which seemed to correspond with that used on the top of a bottle of prussic acid, and three letters from the Prudential Assurance Company, each dated 11 September, and addressed to Bailey, Kate and Hollie, pointing out that the premiums hadn’t been paid since February.

That afternoon, soon after 3.00pm, Dr Bernard Spilsbury, the Home Office pathologist, arrived in Little Marlow to conduct his official post-mortem, assisted by Dr Wills. Externally, he found Kate well nourished, the abdomen was as previously described, and decomposition was advancing. The pupils of the eyes were slightly dilated and the whites of the eyes were congested; a reddish fluid had escaped from the mouth and nostrils. Her hands were clenched, the fingernails were blue.

Internally, the brain and covering of the skull and scalp were, Dr Spilsbury noted, healthy and free from injury. On the surface of the brain there was congestion; there were tiny blood spots on the surface of the heart and lungs; the heart itself was flabby and slightly dilated; the muscles, arteries and valves were also healthy. There was no disease of any kind of the organs. The tongue was red and inflamed, and the back of the tongue and gullet were congested. The stomach contained some fluid, which had a putrid odour, and Dr Spilsbury, like Dr Wills earlier, thought he detected a faint odour suggesting prussic acid. He also confirmed the doctors’ earlier verdict that Kate had been dead not less than three days.

Dr Spilsbury concluded that the victim was at least six months pregnant but there was no sign of any instrumental attempt to secure an abortion. Kate’s death, he told the police, was consistent with prussic-acid poisoning.

Not long after he and Supt Kirby had completed their second, and more comprehensive, sweep of Barn Cottage, and probably around the time Drs Spilsbury and Wills were beginning to minutely examine Kate, Inspector West took a cup of tea into Bailey at the cells in Marlow.

‘If I make a statement to you,’ Bailey asked West, ‘do you think you will be able to get my case settled at the next Assizes?’ The prisoner hadn’t yet seemed fully to have grasped the enormity of the charge against him, having learned that they were due to begin at Aylesbury in just ten days’ time, from 13 October.

‘If you wish to make a statement,’ said West, ‘you can do so; but it will not help you to get your case settled then.’

Deciding against making a statement in that case, Bailey asked instead when the inquest was likely to get under way because, he told West, firmly, ‘I want to attend.’

So ended the first act of what would unfold as a classic three-act drama. Officially, it was now a case of wilful murder. Even in custody, Bailey would remain an active and ever more compelling player in an extraordinary saga whose surface had barely been scratched. For the accused man, it was just another tragic twist on what he would, euphemistically, describe as ‘a simple story of love and devotion’.