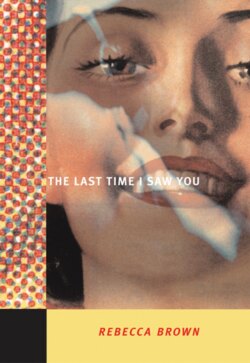

Читать книгу The Last Time I Saw You - Rebecca Brown - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Trenches

ОглавлениеWhen we were kids we were a gang. There was only one other girl, somebody’s little sister who we didn’t like but her mother was never home so her brother had to bring her. We made her be the enemy or a spy or defector or someone already dead or being tortured though sometimes we let her be the nurse if she would go beg somebody’s mother for something for us to eat and bring it back for us. Except for me, there was only her. I didn’t want to be like her and I didn’t want them to think of me like her. At first she tried to tag along with me but after a while she gave up. We all rode bikes together, the rest of us. She only had a trike. We played tree forts and baseball and football and soccer and war. We played in our yards and in the alleys behind our yards and in the vacant lot with all the broken bottles and piles of ancient dog shit and the brown flowered sprung out couch and down past where the road ended and there was a ravine.

We slid down the ravine and scraped our elbows and hands and tore the backs of our pants and coughed on the dirt we had stirred up and ripped our shirts. There was one boy a few grades ahead of us but the rest of us never thought it was strange that we were the ones he played with. I don’t know if he thought about this, then or ever. I hope not. He didn’t need to be more miserable than he was. Nobody should be that miserable. He was the one who had learned about “The Trenches” in school. He told us about them.

The Trenches, he said, were terrible, truly terrible.

The Trenches. The way he said it, the way we all said it forever afterwards, was never merely “trenches” with a little “t”; but always “The Trenches,” capitalized. The Trenches. How we loved to say the words! The Trenches! The Trenches! The Trenches!

We went to the bottom of the ravine in the muddy creek bed where water sometimes ran until our shoes got wet and pretended that we had been, for months, in The Trenches. We pretended that our feet were white and peeling and soft as worms and that we had “Trench foot,” “Trench mouth,” “Trench fever.” When we had to go home we crawled around in our front yards, beneath the box hedges that we pretended were trees in the Black Forest and under clothes lines that we called Electric Wires, and we screamed and grimaced as we climbed over the chain link fences between our yards as if they were electrocuting us. We spread dirt and grass and water from the garden hose on our faces to make us look like we had gotten muddy and sweaty from crawling in the jungle in the Philippines or were in camouflage. We flung ourselves on the ground and shouted, “I’m hit! I’m hit!!” then crawled along as if our legs were broken and our guts were hanging out, trying to get back to our buddies. Then we made more shooting sounds and flipped up off the ground and twisted around in the air then fell back down again and cried and moaned in cheerful agony “I’m hit! Oh God, Oh God, I’m hit!” Then we would groan crawl scrape ooze collapse until one of our brave buddies braved his way out across the bloody body-strewn battlefield to drag us back away from the machine gun fire torpedoes bombs bazookas machetes grenades Gatling guns missile rockets bottle rockets Molotov cocktails cannonballs hydrogen bombs and A-bombs.

The Trenches were terrible. Truly terrible. The Trenches were full of rats and mud and sewer water up to your ankles. The rats were huge, as big as cats, and always hungry, ravenous—they could eat a horse—with huge sharp dripping teeth and they carried horrible excruciating incurable diseases. The Trenches were always cold and dark and slimy and also had snakes in them, huge fat ones, as gross as eels, as strong as boa constrictors, and fast skinny ones more poisonous than the rattlers we had in Texas. The Trenches also stank from all the guys who hadn’t taken a bath in months but also, even more in fact, they stank from all the terrible, horrible, grotesque wounds the guys had gotten that had been left untreated. The guys had arms—whole arms or parts of arms—shot off so they couldn’t even hold their guns with both hands, just one, or a nub but they did hold their gun, if it was the last thing they did, by God, they held their gun. They had legs shot off, one or both, all the way or part of the way, below the knee or in the middle of the thigh so they couldn’t walk any more, just hobble and lurch and fall around, knocking against the sides of The Trench or against each other. Sometimes they’d have to grab you to keep from falling and it was like being grabbed by a zombie. They dragged themselves along the ground through the mud and snakes and sewer water, their smashed crushed limp paralyzed lacerated legs or parts of legs dragging behind them like bags of sand.

They also had their guts shot or stabbed or bayonetted out, or not even all the way out, just part of the way out, which was worse, because you were still alive and could feel everything. Your guts and stomach and intestines were hanging out and you had to hold on to them to keep them from falling into the sewer water where the rats would eat them while they were still partly attached to you and you could feel the horrible rats’ filthy diseasey teeth eating you.

We loved this. We loved being the men who lived in The Trenches doing what had to be done. Nobody else would do it but it had to be done so we did it.

Of course some of them died which is when you would have to lie there still until it was time to go home for dinner or he said you could be alive again for another assault. You didn’t want to die early because then there was nothing to do. You just had to lie there and people could walk on your dead body and you couldn’t do anything because you were dead.

In some ways, though, the ones who died were actually the lucky ones because the ones who didn’t die suffered, they really, truly suffered. The suffering guys would beg to be put out of their misery. When you could you would. You would shoot them in the face, right between the eyes or put the barrel of the gun right on their temple and shoot them there. But that was only if you could. Because sometimes you were so low on ammo you couldn’t afford to waste one single bullet on a guy of yours who was suffering, even if he was begging, pleading, really, truly suffering because you might need that very bullet, it might be your very last, to shoot some Jap or German or spy or whoever was coming into The Trench. So sometimes you had to bludgeon your guy with the butt of your gun or put your boot on his throat and press or just strangle him with your bare hands. Even then, that was only if you could! If you were lucky! And that’s a big If!

If, for example, you were not being bombarded at that very moment by an entire platoon of rabid insane Japs or grenaded by a battalion of ruthless sadistic Germans in which case your guy just had to sit there and suffer, truly suffer, while you tried to hold off the entire Japanese battalion on your own. You couldn’t take care of him while he was laying there suffering or if he was still mobile, and going insane, crawling around on what was left of his bloody stumps of legs and arms which were bloody as meat bones, bloody as T-bone steaks, bloody as dog food, bloody as the dog itself after it was hit by the Camaro, because you had to do what you had to do.

Actually, though, it was often the girl who was just laying there, so she, not he, had to just lay there. Hanging onto her stomach and guts and intestines as we instructed her or her head where her brains were oozing out or her ear was flapping off or her one eye—the other one was just an empty socket—which had been half shot out was hanging down.

We loved—we loved—to play like this.

We all said that some day we could do this all for real.

Actually, though, some of the horribly wounded guys in The Trench had been treated, but only superficially because we didn’t have the right supplies. We could only wrap our bloody stumps with filthy, crusty, bloody, raggedy wrappings that had previously been wrapped around some other guy whose arm or leg or head had been blown off. Then after he had died we took the wrapping off and put it on another guy who was still living even if the new guy might get the dead guy’s germs because it was better to only take the chance of getting your buddy’s germs and dying rather than definitely dying because you lost all your blood, so we wrapped ourselves with filthy crusty rags that had the blood and brains and guts of other dead guys on them around our wounds, which, dangerous at it was, was also like Blood Brothers, even if it was being Blood Brothers with a dead guy, which was good to be.

No one wanted the girl’s rags and she didn’t try to make us take them but sometimes there was no alternative so we took them anyway and she didn’t try to stop us. After a while, she stopped trying anything. She stopped doing anything.

On the other hand, we could also wrap, if there was anything left of them, our own ragged bloody sleeves or pants’ legs or socks or whatever around our bloody stumps.

In The Trenches the guys could only “amputate”—we loved that word too—with their own knives or bayonets, which were steak knives or bread knives, blunt and bloody or serrated, as opposed to doctors’ knives which would have been sterile and sharp, but we had to do it all without medicine or anything to put you under. Only, sometimes, if someone had saved some, you could have a swig or a slug of rum or whiskey. One time someone actually did bring a bottle from their father’s house, Scotch Malt Whiskey, and we all tried it, even the girl. Her brother held her mouth open while the boy who was a few grades ahead of us poured it in, almost all of which I watched although at the very last I closed my eyes which I hoped no one noticed. But then right after that I very quickly drank my slug myself.

But mostly there was no medicine or whiskey so you had to bite on a bullet to keep from yelling out loud. Or if not a bullet, because you didn’t even have any bullets left, not one single bullet left and now you were just sitting in the The Trench like sitting ducks waiting to get it, you would have to bite on the bloody rag of someone who died before you. Then you would taste their blood, which tasted like metal, and sometimes their brains which, he told us, tasted like chicken. You had to put something in your mouth because no matter how much pain you were in you couldn’t scream or moan because the Japs might hear you and find you. You had to be absolutely completely silent. (The girl became the best at this.) If you made a sound your buddies had to hit you for your own good and for the good of the company. Sometimes we put a handkerchief in the girl’s mouth even if she wasn’t making noises. Her brother held her down and put it in and after a while she didn’t even squirm.

When we had to come home from The Trenches at night, we did what we could get away with. We spread Mercurochrome all over our hands and legs and arms and called it “blood.” We drew stitches on our arms and heads and legs and guts with magic markers. One time someone had a jar of mayonnaise and we blobbed it on like pus. We walked with limps we called our “war wounds,” and lurched along like Frankenstein and flapped our arms around or dragged our knuckles along the ground like apes, as if our backs were broken and we couldn’t stand up straight. Once we saw a man like that, or a kid, we couldn’t actually tell. We couldn’t tell how big or small or old he was or even if it was a guy or a girl. He couldn’t stand up and his arms flapped around but we didn’t think of him like a guy who got a war wound in The Trenches. We didn’t think of things like that.

This is what we did when we were kids.

Then we grew up.