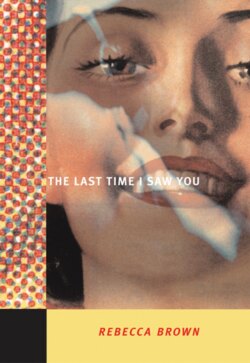

Читать книгу The Last Time I Saw You - Rebecca Brown - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

An Augury

ОглавлениеYou bring me breakfast in bed and have my tea leaves read before I am awake.

I didn’t know this at first. At first I only heard the clatter of teacups, the muffle of your kicking closed the door. “Where are you going?” I cried, half asleep, and heard your muffled voice from down the hall: “Mmmm-mmmm-mmmmm!” It sounded like singing, singsong and sweet. It sounded cheerful. I liked that sound. I liked the sound of you around. But I had no idea what you said.

I tried to wake up earlier but I take time.

Your trench coat was tossed across the foot of the bed.

A week or so after you’d moved in—Did I mention the place had been only mine? That you’d moved into my apartment? I’d wanted you to, of course. I had invited you. Oh how I had invited you! I wanted you near me all the time and told you so. You always had admired the place and you had no place of your own.

I learned much later, too late I think, that you, in fact, had nothing.

I had coaxed and I had begged. I’d almost have done anything. I promised. You laughed with me, affectionately, I thought, and said “OK.” That is, you said “MMMmmmmmm,” which I thought meant “OK” because we cast whoever’s caution to the wind, or so I said, and you laughed at that, though you didn’t ever really actually laugh, not out loud, more half a smile, a raise of half your mouth. Then you moved in with me.

It didn’t take long because you didn’t bring much. Besides, I had enough for both. I had a lot, I thought.

You used to live in a boarding house, a place down near the docks, where drifters lived, until you moved into my apartment. Or our apartment, rather. It took a while to get used to saying that. Our this. Our that. Our everything. You told me, anyway, to watch what I said. I tried.

After a while I woke up early enough in the morning to see you leave. I’d hear, or think I almost heard, the swish of the spoon in the cup of tea and then your mumbling voice, unruffled, calm, and saying things I couldn’t hear, not words exactly, but something wise, more wise than words. But by the time I awoke enough to see, to lift mine eyes, oh lift mine eyes unto you, you were leaving. You had already left.

You always had already left.

And you always had coffee anyway, and it was always black.

One morning, though, when I awoke on time, we stood in the bathroom next to each other. We stood in front of the mirror and we were brushing our teeth and washing our faces and wiping the sleep away from our eyes, well, my eyes. You weren’t. I don’t know when you ever slept. In any event, we were standing together, though not together exactly, rather side by side. You were looking down into the sink. Perhaps you were spitting. I think this was the case because when you next looked up your teeth were clean. Your pretty white shiny lovely teeth were shiny and white and clean and there were these little bubbles of something at the corners of your mouth. I was looking forward, up, across from me, directly in the mirror where I saw the top of your head, your lovely head, the top of which (you’d taken your fedora off) was, to me, as if the sun, as if the pinnacle of heaven, all the milky sticky stars, the tip of the top of the universe, the boss of all that was. I was also looking at my face which was my usual face blah blah blah except for my—something? What?—My eyes. They looked blurry.

Then like they weren’t quite there. Like they were being rubbed out. Like a job an eraser had not quite done. Like a Xerox of a painting that had faded in the sun or like a picture drawn with the stub of a colored pencil that was at its end. A picture drawn on wet paper smudging like fog as if like in steam coming up from vents. I almost couldn’t see them.

“Does anything look weird to you?” I asked, still looking as much as I could into the mirror.

I think you looked. That is, I remember the feeling of movement but I was seeing less by the instant. Things were getting dark with only faded fields of black and gray and movement such as the movement of your head up to look at the mirror whereon our two faces, yours and mine, were or would have been reflected though I am guessing now, having by then completely lost all my ability to see—I could not see—and you said, “MMMMmmmmm?” Or perhaps asked, for it sounded like a question, the purr from your throat sliding up like a cat’s, as if you were wondering, sort of, but also thinking of something else: “MMmmmm-mmm?” Or so I thought. For it was beginning to sound like steam in my ears like the hiss of the steam rising up from vents, like the slush of ice slushing back and forth on the windshield of a sedan.

I remember trying to grab with my hand. I must have dropped my toothbrush for I must have been brushing my teeth too for we did everything together then I thought because we liked to. Our this, our that, etc.

“Does something look weird to you,” I asked, having stumbled, almost fallen in my sudden dark, having grabbed the edge of the sink, not you, for I was beginning to learn.

You didn’t say anything.

Not even “MMMMMmmmm.”

“My eyes looked blurry,” I said, like the colors of them had faded, if there had in fact been color, not only black and white, which is, at last, how I remembered seeing, “then disappeared and I can’t see you anymore.”

I can’t see anything anymore.

You took me to bed. Although I couldn’t see, I knew it was you.

Besides I have never forgotten the touch of your hands, the way you held me and guided me, the way you knew and looked forward to, as you told me, once, I think, each thing and every single thing we did.

You knew before myself as if you made me.

You knew before it happened that it would.

You put me in the bed and then you fed me an invalid’s food: a cup of tea. You took it upon yourself to care for me, a poor, poor invalid, a poor, poor widow without a mite. You are good to me! You gave me a room. You set it up as a sickroom and you kept me there. You let me stay, like a Samaritan, in your apartment.

I was grateful to you and tried to tell. My frustration is that what had happened to my eyes, as if some white thing had grown over them, as if some rubbery skin had sealed them, as if some wax, some plasticy rubbery melted thing had happened to my mouth as well because all I could say was “MMmmmmmm.”

But I want you to know and I hope you do, that it means, that is, I mean: I owe you, Dear, for everything that I can never tell.

You knew what would happen before it did.

You also must know now, I assume, the only thing I know anymore is the truth.

I lay unmoving on the bed and imagine the sound of rain.