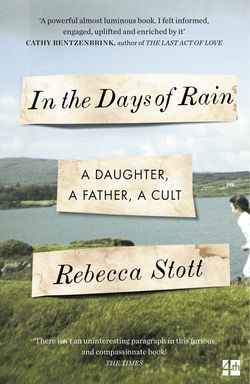

Читать книгу In the Days of Rain: WINNER OF THE 2017 COSTA BIOGRAPHY AWARD - Rebecca Stott - Страница 18

8

ОглавлениеThe Great War broke out in 1914, but as an older man David Fairbairn Stott wasn’t called up until 1916. Following the Biblical injunction ‘Thou Shalt Not Kill’, he refused to fight, and was one of hundreds of Plymouth and Closed Brethren sent south to Wormwood Scrubs prison in London to await military tribunal. He served out his sentence of hard labour in Dartmoor prison along with other religious and political conscientious objectors.

The coincidence was striking. Sixty-three years later my own father would be sent to Wormwood Scrubs too – sentenced not for conscientious objection, but for embezzling money to feed his roulette habit. I was sixteen when my father went to ‘the Scrubs’, as it was known. My grandfather Robert had been fourteen when his father was sent there. He’d been forced to leave school to take care of the shop because his mother had three-year-old Greta and one-year-old David to mind. Our household had suffered too. While I was studying for my A-Levels my mother had bailiffs and debt collectors calling at our door.

My father did not like his father, Robert, but in his dying days he talked about him tenderly. He empathised with him. ‘It must have been hard being the son of a conscientious objector in a fishing village like Port Seton,’ he said, looking at the photographs I’d found of his father as a young man wearing a suit, his hair slicked back with oil, trying to look older than his years. ‘Before the war he’d written poetry and hymns. He was learning fine lettering so he could paint signs for local shops, but when the war came he had to stop all that and mind the shop. Customers gave him a hard time; many of the villagers boycotted the shop. He was only fourteen. My Auntie Bessie used to say that sometimes he’d lose his temper and hurl tins like missiles across the shop.’

My father smiled.

Like father like son, I thought.

‘Things got worse,’ my father said, trying to sit up so he could rummage through the shoebox of photographs. ‘While my grandfather was in prison, my father’s younger brother Morton – he was only ten then – contracted a bacterial infection in his leg; the doctors rushed him to the hospital in Edinburgh. My grandmother had to travel back and forth to visit him every day with baby David in his pram. The doctors had to cut out a chunk of Morton’s leg to drain the poison. They said he wouldn’t recover. When they sent him home they expected him to die.’

There was a little white coffin in this story, I remembered. A little white coffin and a Brethren procession. I’d heard my father tell this story before. But now that he was dying, I knew this would be the last time I’d hear him tell it.

‘The prison warden allowed my grandfather to go home,’ he continued, lost in a photograph of Lizzie pushing the pram along the seafront at Port Seton during the war, ‘so that he could see his son one last time. But by the time he’d got all the way from Dartmoor to Scotland – and it must have taken days in wartime – baby David had died instead.’

‘Meningitis,’ I say, remembering, thinking about how poor Lizzie must have had to break the news to her husband.

‘The Brethren,’ my father went on, ‘carried the little white coffin along the coast to the graveyard in the next village. Then David had to go all the way back to Dartmoor, leaving Lizzie to teach Morton to walk again.’

I’m thinking about Robert trapped behind that shop counter, an open target for the taunts of local lads. Did those boys say the words that all the village must have been thinking – that David’s death and Morton’s leg had been a punishment for his father’s cowardice? That it served those nose-in-the-air Stotts right? Robert must have hurled a fair few more tins then, perhaps even cursed his father. But there would have been older Brethren men looking out for him, I remind myself, and the Brethren sisters would have been helping Lizzie. That’s what Brethren did. At least the Stotts knew they weren’t on their own.

The social stigma would have lasted for a long time after the war ended. Conscientious objectors describe being ostracised for decades: people wouldn’t shake your hand; with a prison record you couldn’t get a job; if you ran a business people wouldn’t buy from you.

The Stotts decided to move the family business south. It wasn’t just the shame of David’s having been a conscientious objector that was making life difficult in Port Seton, my father said. The great herring gold-rush was over, the stocks depleted by overfishing. Neighbours were shutting up shop, selling their boats where they could find people to buy them, moving away. Lizzie’s youngest brother had decided to emigrate to Australia. One of her cousins had moved to Hastings on the south coast of England.

‘My father knew he and his siblings would never find Brethren to marry in Port Seton,’ my father said. ‘There were just not enough young Brethren left. If they wanted families they’d have to go south. My father had been taking the train down to London several times a year for the big London Brethren Meetings. He’d even starting seeing a Brethren girl in London, but he’d kept that secret from his parents. He got his sisters to cover for him.’

I found a photograph of the family taken a year or two before they left Port Seton to go south. They’d dressed up, I guess, for the picture, gone out into the garden behind the shop to get the best of the light. They look nervous and awkward, unsure where to put their hands. Except for my grandfather. He’s standing behind his father, looking straight at the camera. He’s carefully dressed and groomed, sure of himself. He looks like a man who wants to impress. He looks like a man who might have a secret romance.

The Stotts photographed in 1925. From left: Lizzie, Morton, Greta, Bessie, Robert, and David Fairbairn Stott

In 1927 the Stotts moved to Brighton, a seaside town a hundred times bigger and worldlier than Port Seton. Lizzie had cousins thirty miles along the coast in Hastings, but a Brighton Brethren builder had offered the two Stott brothers work on a building site and found them somewhere to live. I imagine the four young Stotts walking amongst day trippers, both fascinated and shocked by street gang fights, piers, parks and a royal palace. Their Scottish accents would have singled them out amongst Brighton Brethren as well as in local shops. They’d have caused a stir in the Brighton Meeting Room.

While Robert and Morton worked on the building site, Greta and Bessie went to Pitman’s College to study secretarial skills and accountancy. After a year, Hastings Brethren helped David to buy a wholesale chemist’s business in the town. The family moved into a flat above the shop and joined the Hastings Brethren assembly. The two Stott brothers, by now in their twenties, would have been looking about for potential Brethren wives. Brethren fathers would have been sizing them up too.

In 1930 a well-known Australian ministering brother called Hugh Wasson arrived in Hastings with his two pretty daughters, Kathleen and Betty. He’d grown up in a big family in Northern Ireland before emigrating to Australia, and he’d promised his daughters a grand tour of Great Britain and Ireland. Robert and Morton offered to accompany the Wassons when they visited the Highlands. Two years later Kathleen sailed halfway round the world again, from Adelaide to Tilbury Docks, to marry Robert. Betty followed two years after that, to marry Morton.

My father’s memoir had begun here, with my grandmother’s sea voyage. Kathleen Wasson, exotic, elegantly but demurely dressed, the daughter of an eminent and established Australian Brethren brother, the granddaughter of a Brethren missionary, had sailed across the world to marry my Scottish grandfather.