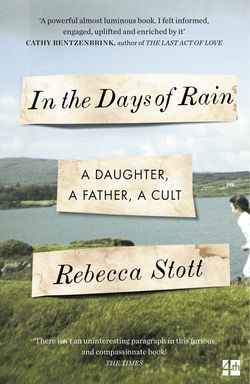

Читать книгу In the Days of Rain: WINNER OF THE 2017 COSTA BIOGRAPHY AWARD - Rebecca Stott - Страница 9

4

ОглавлениеFour years after my father died I won a place at a month-long silent writers’ retreat in a fifteenth-century castle just south of Edinburgh. I was supposed to be writing a novel set in nineteenth-century London, but after a week sitting at a desk staring down over the castle grounds I was deleting everything I wrote, and that wasn’t much. Every paragraph felt hollowed out; every sentence threw me off.

When I walked the castle grounds at dusk, down through the bracken and the fallen and rotting trees to the peat-red river, up to the edge of the mown lawns and the flowerbeds and back round again, I heard my father reciting parts of Revelation or Ezekiel, or Yeats’s ‘The Wild Swans at Coole’, or talking about that thicket of his. His voice echoed through the east and west wings of the castle, through the woods, in the wind. These were just aural grief hallucinations, I told myself, just flickers in my neural pathways. They were nothing out of the ordinary, nothing to worry about.

In the final week of the retreat I joined the other four writers at dusk to swim in the river that curled wide and red-brown over rocks and pebbles through the castle woods. After we’d climbed from the freezing water and pulled our towels and robes around us, we followed the path up the steep riverbank into the darkening wood. I fixed my eyes on the poet’s feet ahead of me, now level with my head, as they pressed into the leaves and bracken. When his foot slipped and he stumbled slightly, I saw, or thought I saw, a plume of smoke rising slowly from a hole in the ground that he’d disturbed.

I felt the scratchings and rustlings in my hair. The first stings began. The poet behind me, dressed in a red robe, had also been engulfed. We ran through the wood back to the castle, tripping over undergrowth in the darkness, shaking our hair and pulling off our clothes, until we were sure we’d outrun them.

We’d had a lucky escape, we told ourselves over dinner. Was it, someone asked, lemon juice or ice you were supposed to put on wasp stings? Someone passed me a tumbler of whisky. I took myself to bed early. The whisky must have addled my head, I thought, because I seemed to be hearing voices that weren’t there.

At three in the morning I woke, my pulse drumming wildly in my ears, fireworks exploding behind my eyelids. When I stumbled to a mirror to prise open a single eye, my face and neck were so swollen, taut and shiny that I stumbled backwards in shock. I was struggling to breathe.

Two days later it was all over: the early-morning drive through the dark to the emergency surgery in the director’s car, the steroids, the dosage of antihistamines large enough to floor an elephant, the semi-coma I slipped into for twenty-four hours. The doctor had counted up the hard lumps on my scalp and neck. Twenty-five stings. Enough to kill someone with an allergy, almost enough to kill someone who’d been stung before in an empty garden when a smoky swarm had risen like a ghost from a hole in the ground.

Not enough to kill, I thought, but enough to make a point.

A few years earlier, I’d discovered that the man dressed in a turquoise and pink Hawaiian shirt sitting opposite me at a Cambridge dinner party was a world expert on shamanism. I’d plagued him with questions, and if I’d failed to observe the to-and-fro turn-taking of dinner-party etiquette, I was not the only one. None of us wanted to talk about anything else.

For fifteen summers he’d lived with a shamanic tribe on the Russian steppes, he told us. He’d studied shamans as they talked their dead down.

‘Talking down,’ I said. ‘What does that mean?’ Death for me had been all about going up there, the transcendent sucking up into the air, into the arms of Jesus. I thought again of the impossibility of that body-weight of my father’s going up there, going up anywhere. Even in the blood-red plastic cremation jar his ashes had been a ton weight.

The shaman expert told us that the bereaved Sora used the shaman as an intermediary to persuade the dead person to go down into the next world.

‘Like laying a ghost?’ I asked.

‘Something like that,’ he said. ‘Though it works both ways for them. The dead and the living both have to convince the other to let them go. It takes a long time.’

Until the relatives had talked down the dead person, he told us, their spirit would be hanging around the village doing bad things, provoking, making people sick, causing the crops to fail. They had to be talked down and into the ground.

In that moment I saw my huge father up on a cliff ledge somewhere, slightly drunk, swaying close to the edge, holding forth, and my siblings and me talking him down. Or trying to. Hadn’t we done that? I asked myself. Isn’t that what we’d done out there at the Mill with the Bergman and the cricket?

But I hadn’t even started. My father was still roaming. Still talking. There were swarms of wasps, acts of provocation. It would get worse. Someone was going to have to talk him down.