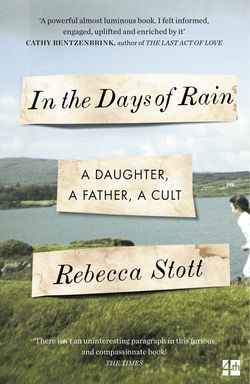

Читать книгу In the Days of Rain: WINNER OF THE 2017 COSTA BIOGRAPHY AWARD - Rebecca Stott - Страница 21

11

ОглавлениеThe Brethren childhood that my father described in his memoir was very similar to my own, but much less circumscribed. Brethren rules were strict in the forties, but nothing compared to the prohibitions introduced in the sixties, when I was born.

What had it been like to grow up as a boy in the Brethren? I’d always felt so cross as a small Brethren girl – not a sulky, smouldering kind of cross, but a fire-out-of-control-sweeping-across-landscapes kind of cross. But I did not dare show it. I was supposed to like being subject. My grandmother did. She’d lower her head when my grandfather was having one of his rages, as if submitting to her bullying husband was a way of serving the Lord Jesus. Sometimes I’d have to bite my lip so I wouldn’t howl with rage when I watched her. It was so unfair. Why did women have to do exactly as the men said? Just because Paul had said so? Who was Paul, that he could say such things and have everyone follow his instructions blindly like that? Even thinking those thoughts was a terrible sin, my grandmother would have told me. It was against scripture.

But what if I’d been a Brethren boy? My father would have grown up knowing he’d be head of his household one day, head of the family business, even an important ministering brother if he was good enough at talking about the scriptures. He could preach in Meeting. He could shout in his house. I didn’t much like any of the Brethren boys I knew. They called me ‘just a girl’, and I grew up knowing that I’d be ‘just a girl’ until I became ‘just a woman’. Would I have liked the Brethren boy my father had been? I don’t think so. He’d have probably called me ‘just a girl’ too.

‘If we were at home for the Lord’s Day,’ my father wrote, ‘we set out on foot for the eleven o’clock Meeting at The Iron Room. We were expected to walk quietly and sensibly: my brother and I usually walked ahead and my father and mother followed, pushing my baby sister in the pram. Each of us carried a hymnbook and a Bible. This was part of our testimony – amongst whom ye shine as lights in the world.

‘But there weren’t many people about to shine on,’ my father complained. ‘There’d have been Baptist and Methodist services in Kenilworth at the same time and there was certainly a Holy Communion at St John’s Church in the other direction but,’ he wrote, ‘we only ever saw Mr and Mrs Bert Clayton and Mr and Mrs Foster, the two Brethren couples who also lived in Waverley Road. They were either ahead or behind walking on the other side of the road. We never walked with them. I have no idea why. Mr Foster had a long neck and a very prominent Adam’s apple. He was tall and thin and he walked quickly in a kind of stalking manner. His much shorter wife struggled to keep up with him. My father called them “the long and the short of it”.’

In the forties and fifties all the Brethren sisters wore hats. In the scriptures, the Apostle Paul had stipulated that women’s heads should be covered when they were ‘in the temple’, my father explained, but that men were to have their heads uncovered. For a group of post-war fundamentalists living in the British suburbs two thousand years later, this injunction of Paul’s proved difficult to follow. One of the early Brethren leaders had made a rule that if men were supposed to have their heads uncovered in the temple, they should have their heads covered on their way to it. So the brothers wore hats to the Meeting, and hung them on the rows of hooks at the back of the Iron Room.

When my father was a child, the lack of symmetry in this hat rule had vexed him. He’d asked my grandfather why the sisters weren’t carrying their hats to the Meeting and putting them on when they went in. His grandfather laughed, but didn’t answer the question. My father wasn’t sure he knew the answer. He’d begun to wonder if there were other things his father did not know.

‘The Morning Meeting in The Iron Room,’ my father remembered, ‘lasted for just over an hour. Brethren boys had to make sure that all the sisters had any cushions they wanted before the Meeting started, and a hassock, or footstool. Hassocks were piled at the back of the Room, fat and thick and stuffed with some kind of coarse material, some patterned, some plain. All the sisters had to have one to put their feet on. The chairs were arranged in a circle around a table covered in a white cloth. On the table there was a goblet, a loaf of freshly baked bread in a basket, and a collection box.’