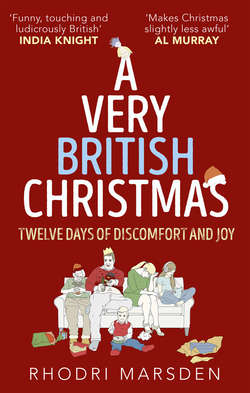

Читать книгу A Very British Christmas: Twelve Days of Discomfort and Joy - Rhodri Marsden, Rhodri Marsden - Страница 6

Twelve Gifts Unwrapping

ОглавлениеDawn: I love Christmas, I love birthdays. I get more excited about watching people open their presents than they do.

Director: You don’t seem to have bought much, Lee?

Lee: No, I don’t buy into it. It’s a con. What I usually say to Dawn is work out what she’s spent on me, and take it out of my wallet.

The Office, Christmas 2003

Nothing says ‘I love you’ like eighteen stock cubes in a limited-edition tin. It may not seem that way when you unwrap it and wonder why you’ve been earmarked as the perfect recipient of some dehydrated broth, but you have to remember that gift giving doesn’t come naturally to everyone. The combination of an obligation to buy presents along with a lack of imagination and an immovable Christmas Eve deadline results in high-pressure situations, with people getting shower mats they don’t want and being expected to show gratitude for them. The random selection of items that pile up under the average British Christmas tree is testament to our erratic emotional intelligence; we can be pretty good at giving the right things, but where we truly excel is giving completely the wrong things and then being told in passive-aggressive style not to worry about it because ‘it’s the thought that counts’, when it evidently isn’t.

We’ve been giving gifts at Christmas for many years. The recipients inevitably give us gifts in return, and so the following year we have to give them gifts again, and so it continues, for ever, in what French sociologist Marcel Mauss referred to as a ‘self-perpetuating system of reciprocity’, but in French. The whole thing has now escalated to a point where a truly desperate person can (and will) spend a meagre sum on an ‘I’m A Twat’ mug for their great-uncle. This is something that Dickens’s Ghost Of Christmas Future could never have foreseen.

In 1996, a Canadian academic called Russell Belk came up with six characteristics of the perfect gift, and it’s worth listing them here, if only to observe how few of those boxes are ticked by an ‘I’m A Twat’ mug:

1. The giver makes an extraordinary sacrifice.

2. The giver wishes solely to please the recipient.

3. The gift is a luxury.

4. The gift is something uniquely appropriate to the recipient.

5. The recipient is surprised by the gift.2

6. The recipient desired the gift and is delighted by it.

Number four is critical. Choosing a gift that’s carefully tailored to the needs and wishes of a friend or relative requires levels of insight and empathy that are beyond many of us, and that’s where luxury bath salts come in. But for those who feel embarrassed every time they buy luxury bath salts, inspiration can be sought from businesses such as The Present Finder, set up in 2000 by Mark Ashley Miller. ‘I always enjoyed finding unusual things for people,’ he said to me, ‘and I’d like to think that I’m good at it. For example, my wife likes to wash her hair every other day, but she can never remember whether she washed her hair the previous day or not. So last year I got her a personalised gift, Fiona’s Hair Wash Day, which she can put up in the shower and move a token along each day so she knows if she washed it or not. She uses it every day; it’s really useful, and it’s unusual. It ticks all the boxes.’

“I haven’t a clue which one of these he might like.”

Whatever skill it might take to come up with something as spine-chillingly practical as Fiona’s Hair Wash Day, I don’t have it. I’m rarely able to detect a need that someone has and then satisfy it with something clever tied up with ribbons. I’ve had a couple of brilliant flashes of inspiration in my time, but only a couple, and my persistent inability to think of decent gifts for others is mirrored by a failure to come up with ideas for things I want for myself. Every year my mum asks me and I never know what to say; one year I remember her ringing me for the fourth time with a note of desperation in her voice and saying, ‘Cutlery?’ (The threat of cutlery, or worse, ‘surprises’, forced me to come up with some ideas which, in retrospect, probably weren’t as good as cutlery or ‘surprises’.) This trait is shared by many people, and particularly men, according to Mark. ‘Everyone seems to struggle with buying things for men,’ he says, ‘because typically a man says, “I don’t need anything, and if I did want something I’d buy it myself.”’

Blackburn, Christmas 1988

One Christmas I bought my dad a Remington Fuzz Away. Not unusually, it was very hard to buy presents for him, but he absolutely adored this thing. He used it on all his shirts, other people’s clothing, furniture. He would look you over, notice any pilling on the fabric, and ask if you wanted him to remove it. He told everyone about the Fuzz Away and used it until it fell apart, and then he worked out how to hold it together so it still functioned. I never saw him as keen about anything, ever, let alone a Christmas gift.

S. S.

In 2008, a company called Life of Jay responded to the apathetic shrugs of British men in the lead-up to Christmas with a product called Nothing, consisting of a clear Perspex ball full of air. At a stroke, the company fulfilled the specifically stated wishes of several thousand men; they asked for nothing, and they received Nothing in return. Nothing (or ‘Nothing’) wasn’t what they really wanted, of course – but it’s their own fault for never expressing any delight at small things over the course of the year, and instead developing secret desires for ridiculously big things like yachts, or expensive Bang & Olufsen speakers that promise ‘optimum precision in sound’. These things are forever destined to remain pipe dreams, and men should set their sights a little lower, maybe somewhere just above luxury bath salts.

The annual tit-for-tat reciprocity of Christmas giving3 begins with Christmas cards, a tradition that only started in the mid nineteenth century but one for which the British continue to show great enthusiasm. The Christmas card industry is surprisingly resilient; we bought more than a billion cards in 2016, and they’re still seen as a more appropriate display of familial affection than sending your uncle an e-card with a virus that key logs his computer and sends his credit card details to a hacker in Minsk. Unlike festive JPEGs, the exchange of physical cards is constrained by Royal Mail’s last posting dates, which feels like a quaint concept in this Internet age. Some people fail to get their cards sent in time because they’re disorganised, but others do it very deliberately as part of a covert psychological operation.

My mum keeps a list of all her friends. Every year she goes down the list and writes everyone a card. Then she waits. The day after the last posting date for Christmas, she puts a second-class stamp on the envelope and then posts them. This ensures that if someone hasn’t already sent her a card by that point, they don’t have time to get one back to her. My mum thinks that these people have to remember her of their own volition, and not be reminded with a card. If they fail to remember, they get removed from the list.

But if she forgets someone and they send her a card, she obviously has time to send one back. So she doesn’t hold herself to the same standards that she holds everyone else. And if everyone adopted her system, the whole Christmas card industry would collapse. It’s ridiculous.

G. G., Nottingham

If you thought it was difficult to think of original gift ideas, spare a thought for the people who are tasked with designing and writing our Christmas cards, year in, year out. The struggle to come up with new concepts that might appeal to a fickle British public gets more difficult by the year. Millennials may have no interest in a traditional scene featuring a wintery landscape, twinkling stars and Robin Redbreast; they may prefer something a bit edgier, like someone in a Santa hat flicking a V-sign with the caption: ‘Fuck Christmas, I’m Getting Twatted Instead.’

I spoke to an editor at a greetings-card firm on condition of anonymity because she didn’t want to get the sack, which is fair enough. ‘You’d think it would be easy,’ she said, ‘but there’s a lot to think about. For example, you can’t use the word “I” in a greeting in case the card is being sent from more than one person. The main problem is making the messages seem personal, but also sufficiently vague for lots of people to want to buy them. And every year we have to come up with new Christmas puns, but they’ve all been done. They really have. We’ve gone a bit delirious with it, honestly.’

I used to spend every Christmas within a few miles of the Welsh village of Bethlehem, which in December becomes a magnet for people who want their cards to have a Christmassy postmark. (Most people don’t even read postmarks, but again, it’s the thought that counts.) ‘People come a very long way to get a stamp,’ says local resident Des Oldfield, ‘but we don’t actually have a Post Office here any more. For a while people were taking their cards to Llandeilo instead, and they were sent on to Cardiff to be postmarked with “Bethlehem”! What a scam! They may as well do it in London! So we offer our own stamping service from a café here in Bethlehem during December, from Monday to Friday. The post office lets us stamp the envelopes as long as we don’t frank the stamp itself. It’s a nice oblong blue stamp which says, “The Hills Of Bethlehem”, and I think people prefer it – because who reads postmarks anyway?’ (Exactly what I was saying, Des.)

The other unusual postmark knocking about over Christmas is ‘Reindeerland’, which adorns envelopes sent by Father Christmas (who definitely exists) to children who have made the effort to write to him. In the UK he has been assigned the rather cute postcode XM4 5HQ, and every year hundreds of thousands of children use it to send beseeching begging letters. He actually replies in person, and it’s definitely not dealt with by a team of people in Royal Mail’s national returns centre in Belfast. OK, hang on a second. If you’re excited about the prospect of Father Christmas visiting you this year, I suggest you turn to page 17 while we deal with some issues that don’t concern you.

Birmingham, Christmas 1988

I grew up poor in an Islamic family in a terraced house near Aston Villa football ground. We had nothing. My dad was a jailbird and my mother worked as the cleaner at the local fire station. But growing up, as the days got shorter and the nights got colder, came the onset of Christmas, and it was the best thing ever. Trees in people’s front windows, the tinsel… Christmas adverts were joyous and we always had a catalogue. We never ordered from it, but I would thumb through, picking out the toys I wanted, knowing I would never get them.

In our front room the fireplace had issues. It used to have a gas fire, but we couldn’t pay the gas bill so my dad ripped it out and taped it up with a piece of white board. But for me this was a problem. How was I going to get the present Santa had thrown down the chimney for me? The other kids got presents. Santa surely wouldn’t deny a Muslim child because, you know, he’s Santa. So I figured my presents were being stockpiled behind that piece of card. They were safe. I told no one in my family in case they took them, but Santa and I had a pact.

When the card eventually got taken away, there was nothing but dust and cobwebs. I thought with all my heart Santa had my back. Instead he turned out to be a bastard. Christmas is a bastard. Doesn’t stop me loving it, though.

A. S.

It’s impossible to write a book about Christmas without addressing the question of belief in Father Christmas. Last year I was invited on a radio programme to talk about matters pertaining to Christmas, and I was sternly informed by the show’s producers not to make any reference to the possibility of Father Christmas not being real for fear that irate parents would jam the switchboards, furious at their offspring having been mentally scarred. In 2011, the Advertising Standards Authority received hundreds of complaints about a Littlewoods advert that appeared to suggest it was parents, not Father Christmas, who brought presents into the home. The ASA allowed the advert to continue running, but preservation of belief in Father Christmas, rather like vaccination, does rely on everyone buying into it in order to avoid widespread misery.

Runcorn, Christmas 1977

In the mid to late 1970s, having a new hi-fi was a big deal, and taping ambient sound from that hi-fi felt like entering the realms of science fiction. One year my dad suggested that we just ‘leave the tape recording’ overnight, so we could hear the sound of Santa arriving. We left out a mince pie and some brandy as usual, and before we went to bed we hit those two chunky Play and Record buttons simultaneously.

On Christmas morning, Dad played the tape back. After a while, we heard footsteps, an exclamation – ‘my, what a lovely mince pie, ho, ho, ho’ and a jangling of sleigh bells, which my mum had contributed to add that important level of verisimilitude. To a 5- or 6-year-old mind, this was irrefutable evidence. It kept us believing for another year, anyway.

R. B.

Father Christmas hasn’t always been a benevolent bringer of presents. We’re told by historian Martin Johnes that Father Christmas was originally ‘an unruly and sometimes even debauched figure who symbolised festive celebrations’, but he merged with the American figure of Santa Claus during the nineteenth century to become a red-coated one-man logistical solutions unit. (Contrary to popular belief, it wasn’t the multinational force of Coca-Cola that imposed a bearded, rotund figure upon unwilling Christians. He was already chubby and dressed in red and white before Coke started promoting him.) By the early to mid twentieth century Santa (or Father Christmas) became the figure that was blueprinted a hundred years earlier in the American poem ‘A Visit from St. Nicholas’ (also known as ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas’), and as the reindeer, sleighs, toys and chimneys of that poem became cemented in our culture, Father Christmas became almost too big a deal. Telling the truth to children was out of the question. So we keep up the pretence for a period that can last for as long as a decade, partly to maintain an element of Christmas magic, partly as a parenting tool to enforce good behaviour by threatening his non-appearance. You better watch out, you better not cry, you better not pout, you better tidy your bedroom.4

Essex, Christmas 1985

One year my parents couldn’t afford enough presents to fill our stockings from Santa, so they added some gifts from friends and family to bulk it up a bit. But they forgot to take the label off one of them, which was a mug, ‘With love from Ian’. I thought Santa had chosen me, of all the world’s children, to reveal his real name to, and was beside myself with excitement. I remember returning to school and telling everyone, but feigning nonchalance. ‘What? Yeah, his name’s Ian. He told me.’ What an idiot.

R. M.

In an ideal world, kids come to terms with Father Christmas not being real over a number of years, via a slow awakening process. They quietly realise that the mileage that he’s caning with Rudolf and friends over the course of a night doesn’t add up, and the fact that he’s in multiple places simultaneously doesn’t make sense, particularly as he seems to be a lot fatter in Debenhams than he was at the town hall. The moment where kids realise that it’s not Santa filling their stockings should represent a kind of blessed relief because they were starting to question their own sanity. This, however, is not always the case.

Newport, Christmas 1985

On Christmas morning the tradition was that we’d wake up and feel at the end of the bed for the stocking, which was filled with small presents and maybe a tangerine or a mini Mars bar in the toe. But one year we woke up and the stockings weren’t there. I would have been nine. My brother and my sister and I all congregated in one bedroom, saying, ‘Oh my god, I’ve not had a stocking, have you had a stocking?’ Then we looked in our parents’ bedroom, and they weren’t there. This was really weird.

It was still dark. We ran downstairs, and the lounge door was shut, and I remember us saying, ‘Oh god, what if Santa is still in there? Do we go in?’ My brother pushed the door open and we saw that the light was on. We peered round the door, and on the sofa were my parents, asleep, with empty wine bottles around them, halfway through doing the stockings, and my dad with his hand inside one of them. And I swear, because I believed in Santa so much, my first thought was, ‘Mum and Dad are stealing our presents!’ We woke them up and they were horrified. My mum was indignant (‘What are you doing down here?’) but my dad was really upset. He knew that he’d ruined Christmas. There was some weak attempt at explaining it away, but that was the end of believing in Father Christmas. At that point, we knew.

A. M.

The mystery of who brings us our presents is recreated in the workplace with Secret Santa, an annual tradition marked by the high-stress drawing of lots, in which everyone hopes they don’t get their boss. Secret Santa adds layers of unnecessary complexity to office politics that may already be fraught: cheap novelty gifts can be deemed insulting, ones that cost more than the specified £5 or £10 can be seen as pathetic attempts to curry favour, and inappropriate ones such as edible knickers or plastic handcuffs can end with a summoning to the HR department for having violated the terms of employment.

Secret Santa pros will manage to come up with three or four decent gifts from the 99p section of eBay, but mischief-makers will get the biggest present they can find that’s within the spending limit, and come in early in order to haul 50kg of building sand out of their car and into the workplace under cover of darkness. If Secret Santa feels too much like hard work, the worldwide web now hosts a number of online Secret Santa tools which suck out any joy from the process, with questionnaires and links to products on Amazon at that particular price point.5 Grim.

Hertfordshire, Christmas 2011

In my first proper job I decided to ‘bring the office together’ with a Secret Santa because it had always worked brilliantly with my friends. I remember that I had to really persuade one particular guy to join in, and was surprised when he turned up the next day with a wrapped gift. This turned out to be a box of Matchmakers and a Chas & Dave CD. When the recipient opened it, she ran into the stationery cupboard and started crying. Apparently Chas & Dave provoked some deep, distressing memory associated with her father.

N.H.

Secret Santa may result in some delicate situations as colleagues compare their respective gifts, but things are no less intense in the family home. The ceremony of gift giving is like a strange one-act play staged in the living room, where moments of genuine pleasure are broken up by Oscar-worthy feigned delight, artificial surprise, awkward silences, suppressed fury and insincere thank yous. It’s astounding, really. If everyone was required by law to react honestly to Christmas gifts as they unwrapped them, we’d see a nationwide break-up of the family unit as we know it, and a lot of very long walks being taken on Christmas afternoon.

This very loaded, intense period of time generally begins at some ungodly hour on Christmas morning if you have small children, slowly moves to later in the day as those children get older, and then zings back to 6 a.m. as those children have their own small children. If your family happens to observe the traditions of mainland Europe, you might open your presents on Christmas Eve – but that’s ridiculous, as it leaves you with nothing to do on Christmas Day except wish that you hadn’t already opened your presents. My own family manage to work up some enthusiasm for unwrapping by late morning. We proceed painstakingly around the room, sizing up the presents, tapping, shaking, rattling, then unwrapping a present each in turn, with my dad saying, ‘Ooh, what have you got there?’ in a strangely high-pitched voice that he only ever uses at Christmas (and the question is ridiculous because everyone knows what everyone is getting as we specifically asked for this stuff a month earlier). We don’t have that many presents, but it takes ages. It really stretches out, like a fifth set tiebreak at Wimbledon and just as exhausting.

Bath, Christmas 2006

My dad’s brother’s wife, who I affectionately term Aunt Hag, has always had it in for me. I have a younger brother she adores, and she loves my mum and dad, but she’s never liked me, and this has always been reflected in the presents she gets me. My parents receive wonderful gifts from her, but mine push the boundaries of the word ‘gift’. I got congealed nail varnish from her one year. When I was about 5 years old I remember getting a yellow My Little Pony umbrella with a hole in it. For years I would try to point out to my parents that this was going on, but they’d stick up for her and say I was being ungrateful.

The last time I visited her at Christmas was ten years ago, with my parents. I opened up my gift and it was a pair of rusty earrings. Seriously. Then, for the next half hour, I watched as my parents unwrapped all these gifts that she’d lavished upon them. As I sat there, we started to look at each other and laugh. That was the point when the penny dropped, when they realised that my aunt actually does hate me. I don’t visit her any more because it’s just awful. Her presents aren’t just bad, they’re almost malevolent.

R. O.

It’s basic human decency to spread the love equally; my friend Dee recalls with anguish the Christmas Day when her grandmother gave her a packet of biscuits and her brother a cheque for £2,000.6 I really hope that it isn’t always girls who come off worse in these situations, but another friend, Helen, tells me of the traumatic occasion when her brother got a brand new bike and she got a loom (‘14-year-olds do not want two-foot wide peg looms for Christmas,’ she says). With luck, however, everyone will be satisfied with their haul and won’t start threatening each other with vicious-looking sprigs of holly. Some of the most difficult scenarios involve two people who’ve agreed between them not to do ‘big presents’, only for one party to secretly row back on that promise and decide to give an absolutely enormous present, leaving one person with a DSLR camera and the other with some shower gel. This is really unpleasant to witness and can only be resolved via delicate arbitration and a phone call to Relate.

Whether it goes well or badly, the ceremony usually ends with everyone sitting amid a blizzard of wrapping paper that you’d definitely roll around in if you were a dog, but you’re not, so best to leave that to the dog. Present wrapping is the only art form we show our appreciation of by ripping it all to bits, whether it’s finely detailed origami or roughly Sellotaped crêpe paper. Given the mundane nature of the majority of gifts, present wrapping should give us a perfect opportunity to lend them a personal touch – but we’ve even started contracting out the wrapping because we’re lazy and we’re rubbish with Sellotape. ‘A lot of the skill of present wrapping is down to patience,’ says Julie Gubbay, who is great at wrapping presents and has her own business called That’s A Wrap. ‘People just give up after the third present, they get sick of it. But I was always good at it, because I really want them to look perfect. Pyramids and cylinder shapes are hard, though. One year I had to wrap up 200 toilet rolls. Don’t ask. It was a nightmare.’

Southsea, Christmas 1974

My dad was a very creative, inventive man who liked to make an effort with presents. The big present for my mum one particular year was a big wicker Ali Baba laundry basket. It was from John Lewis, it was bright orange and it was a Very Big Deal. The idea was to wrap it up like a giant cracker, so he got all of the children involved with Sellotape and scissors and bright green crêpe paper. We wrapped this basket up and placed this huge surprise next to the Christmas tree, although my mum obviously knew what it was all along.

On Christmas Day it became clear that there was no film in the camera. Normally we’d have loads of photos taken on Christmas Day, but we couldn’t buy film because the shops were shut, so my dad decided that we’d be very careful with all the wrapping paper, keep it all, and then recreate Christmas a few days later when he’d bought some film.

The Sunday after Christmas I remember coming home with my Brownie uniform on, and we all had to get changed into the clothes we were wearing on Christmas Day. We rewrapped the presents, including this laundry basket, and there’s a photo of us pulling this giant cracker and opening it. Then we recreated other key scenes from Christmas – and you can tell they’re recreated from the photos because we’re doing things you wouldn’t do on a normal Christmas Day, like me and my brother and sister pretending to admire the decorations. Looking back it was such an odd thing to do, but it was basically because my dad was so proud of the way we’d wrapped up the Ali Baba.

J. H.

For all the effort there has been to smash gender stereotypes, the typical haul of Christmas presents hasn’t changed much over the years: practical stuff for men, luxury stuff for women and a squeaky ball or a chewy stick for the pet.7 Each year brings a must-have children’s toy, from floppy Cabbage Patch dolls in 1983 to flippy Pogs in 1995 to eggy Hatchimals in 2016; many of those Christmas hits represent a kind of collective psychosis where we meekly cough up for them because we have neither the patience nor the imagination to think of anything better. The child who receives the coolest present may well end up provoking the ire of their siblings (e.g. space hopper stabbed with penknife), but sometimes those fashionable, much-hoped-for gifts simply don’t materialise. One year a friend of mine was convinced that his main present would be a Judge Dredd role-playing game, but it turned out to be some cork tiles, a disappointment so acute that he still feels the pain decades later. Most gifts deemed to be ‘wrong’ by kids are usually down to adults failing to second guess their offspring’s rapidly shifting whims, but for older recipients, ‘wrong’ gifts come in a much wider variety of sinister forms.

“And why the hell do you think that I need a stress ball?”

For starters, there’s talc. Let’s get talc out of the way immediately. Then there are ‘rude’ presents, like Quartz Love Eggs or Hematite Jiggle Balls, which have ended up under the tree but really shouldn’t have. (‘Don’t open that now. Helen, open it later. HELEN, DO NOT OPEN THAT.’) Present giving can be a high-stakes gamble; it’s not difficult to get someone something that they are guaranteed to ‘quite’ like (scented candles, socks, books), but a lot can go wrong in the pursuit of stunt gifts that have a 10 per cent chance of hitting the mark and a 90 per cent chance of provoking stern looks.

Merseyside, Christmas 1984

On Christmas Day, my dad’s brother, John, came around to give us our presents. John was a bit of a legend. He never usually bothered with Christmas, but this year he’d given the five of us a massive washing-machine-sized box, each. They were all wrapped up, sitting there in the living room. Being 11 years old I was really excited by this, but my mum and dad would have known that something was up, especially when John got his camera out to take photos. Anyway, I wrenched open the box and a live duck flew out. I crapped myself. There’s a picture of me somewhere leaping back with this duck approaching me. John had bought us five live ducks.

C. S.

An entire book could be written about men’s failed attempts to buy appropriate gifts, particularly for the people who, at least on paper, they’re supposed to be in love with. Receipts for lacy stuff from Intimissimi or Ann Summers must never, ever be mislaid, because they’re as integral a part of the gift as the goddamn lingerie. Ditto perfume: if the recipient hasn’t already expressed a preference, buying scent for them is exceedingly risky, like buying them a pair of shoes. Some men, however, make no effort to be romantic whatsoever.

Sheffield, Christmas 1992

I remember I was at university, and I went to visit my boyfriend in Sheffield just before Christmas. He said that he’d been thinking about what to get me, and he’d decided to get me a Ladyshave. And I thought, well, that’s awful – for all the obvious reasons – but I just laughed. I think I was waiting for a punchline, like ‘not really, I’ve got you a diamond.’

But on the day I left Sheffield to go back home for Christmas, we walked through the town centre and we stopped outside Argos. He asked me to wait there while he went in. So I stood there, thinking that it can’t be as bad as I think it’s going to be, he’ll salvage this somehow. But he came out with an Argos carrier bag, with a box inside, which did indeed contain a Ladyshave, and he gave it to me. I said thank you, turned and walked to the station, and I remember sitting there on the platform, thinking my god, my boyfriend’s got me a Ladyshave for Christmas. He even told me he was going to do it. And I didn’t stop him.

H. W.

Let’s also cast our mind back, briefly, to the second of Russell Belk’s aforementioned perfect gift characteristics: ‘The giver wishes solely to please the recipient’. As we know, people can sometimes give unto others gifts that they want themselves, an act that’s laughably transparent. The mother of a friend of mine is obsessed with owls. Her daughter doesn’t share her obsession, but one year her mother presented her with a huge gift-wrapped present, about three feet in height. It was a giant plastic owl.

Then there are the mysterious, last-minute presents with no obvious thought put into them, just objects, random objects, which can be bought, and occupy space, and can be wrapped up, so they’ll do. I don’t know, maybe a lampshade, or a box of plastic suction hooks, or a bag of pizza base mix, or a bottle of Vosene with a promotional comb Sellotaped to the side, or a Healthy Eating calendar with the price still stuck on, or an unusually shaped thing with no obvious function and no instruction manual to shed light on what it might be. This category of present can be borne out of desperation, or stinginess, or just a dislike of Christmas. But for some families, inexplicable bags of presents can start to become a tradition.

My mum grew up after the war, and she has that mentality of not spending money on things you don’t need. So on Christmas morning, we come down to the living room, and we say to the kids, ‘OK, Grandma’s presents are there in the corner, and we’re saving them until last.’ They’re always in a Lidl carrier bag, and they’re wrapped in whatever paper happens to be lying around, because she believes that Christmas wrapping paper is a waste of money. And the presents are legendary. She doesn’t ask us what we might like, she just gets whatever she wants. A key ring with a cat saying ‘Always Yours’ on it. A can of WD-40. Anchovy paste. I quite often get walnuts, which I can’t stand. Her labels are amazing: she once got me Peter Kay’s autobiography, which was nice enough, but she wrote on the label: ‘I got this in a charity shop’.

It’s not just thrift. She’s thinking things over in her mind about the past, and it comes out in the presents. But in that moment on Christmas morning it’s difficult to follow her thought processes. I mean, the last thing you’re expecting on Christmas morning is a can of squid in black ink. But we sit down as a family, and say, ‘OK, who’s got the best present from Grandma?’ Last year my 19-year-old son, who had just started at university, got a roll of Sellotape. My mum might even have been using the Sellotape to wrap other presents and thought, ‘Oh, that’s what he’ll need’, and then wrapped it up. People think her presents are hilarious, and they are. But to be honest, they’re also really touching.

P. S., Chesterfield

What with the passive-aggressive fallout from misjudged gifts – the jumper never to be worn, the Vengaboys album never to be enjoyed – it’s little wonder that people resort to less imaginative, more practical ways to tick the present-giving box. The bleakest manifestation of this is the tenner in the Christmas card, particularly if two people give each other a tenner in a Christmas card, the Yuletide equivalent of the nil–nil draw. Vouchers may seem more thoughtful and less vulgar, but let’s face it, vouchers are just cash that you can only spend in one place. (‘Why are you placing such unreasonable restrictions upon me?’ is the perfect thing to yell at anyone giving you a voucher this Christmas, although I accept no responsibility for the fallout that may result from this.)

The truth is that small stacks of envelopes just don’t look that good under the Christmas tree. The trend of giving ‘gift experiences’ only adds to that stack, with envelopes containing printed-out emails on which people have scribbled things like ‘you are going bungee jumping in February’ or ‘have a great time rallying at Prestwold Driving Centre’. Then there are the envelopes containing apologies for things that haven’t turned up yet – ‘bread making machine coming in early January’ – although it’s worth being explicit about this kind of thing. Give a child a photograph of a bicycle in an envelope with no accompanying note, and they are likely to experience several seconds of turmoil until you explain that they’re being given a bike and not a photograph of a bike.

No, to fulfil the traditional image of Christmas, you need big stuff wrapped up big (or small things nestling gently on velvet cushions in presentation boxes). But for many people this eye-watering outlay on gifts isn’t ethically or environmentally sound. As the commercialisation of Christmas grows ever more rampant (see Six Bargains Grabbing, page 113), there’s a snowballing temptation to outdo the excesses of the previous year’s splurge, and some families now find themselves unwittingly obliged to fill a Christmas Eve Box. For those who remain blissfully unaware, the Christmas Eve Box is just a load more presents but given a day early. It was suggested in The Daily Telegraph in 2016 that the Christmas Eve Box has become a ‘a charming new tradition’ – but let’s be honest, it’s about keeping kids quiet as their anticipation of Christmas Day reaches unbearably frantic levels, like throwing red meat to the wolves.

This zealous pursuit of materialism may prompt the most politically left-leaning member of the family to abandon traditional gift giving, choosing instead to buy everyone charitable donations to good causes which manifest themselves in the form of a certificate and months of email spam from a panda. It’s a position I have sympathy with, but it’s possible to acknowledge the excesses of modern living and also accept that presents can be lovely things. Few things are as heartening as going for a walk on Christmas morning and seeing kids on new bikes that are ever so slightly too big for them, and while there’s no doubt that Christmas comes with an obligation to give stuff (perhaps too much stuff) it also presents us with a wonderful opportunity. Because, if you do it right, it’s possible to make someone’s year, and create a memory that can last a lifetime.

Watford, Christmas 1982

When I was a kid, I wanted a ZX Spectrum. I knew my folks couldn’t afford it, so I started to save up. I had a paper round and did other odd jobs. I compiled a list of all the things I would need – computer, joystick, even that funny little thermal printer they had. I put all the prices on my list and was committed to about a year’s worth of working and saving. I asked my parents for money towards the goal.

On Christmas morning, I got the normal sackful of ‘little’ presents and my ‘big’ present was handed to me by Dad. It was a cheque for £35 and I was delighted because that was a lot of money for me – and them – at the time. Then, Dad said to me – ‘Actually, give that cheque back. We might need to think about this.’ I paused and gave him the cheque back. He turned the TV on and slid a wooden tray out from underneath the telly. On it was a brand new ZX Spectrum, and the telly was beaming out the game ‘Harrier Attack’. I burst into happy tears. So did my parents. Best present ever, even now.

S. N. R.