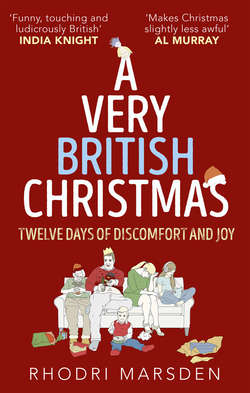

Читать книгу A Very British Christmas: Twelve Days of Discomfort and Joy - Rhodri Marsden, Rhodri Marsden - Страница 7

Eleven Sherries Swigging

ОглавлениеBryn: Doris, will you join us in a Mint Baileys for Christmas?

Doris: I won’t, Bryn. I’ve been drinking all day. To tell you the truth, I’m absolutely twatted.

Gavin & Stacey Christmas Special, 2008

I noticed when I was young that Welsh people of a certain age would make this peculiar whooping noise whenever they were surprised, shocked or delighted. It sounded like a slower version of the ‘pull up’ siren that goes off in the cockpit before an aeroplane slams into the side of a mountain, although it obviously wasn’t as scary as that. When you heard the sound you’d definitely raise an eyebrow, but it wouldn’t prompt you to leave all your belongings, remove your high heels and make your way to the nearest exit (which in some cases may be behind you). I’d hear that noise a lot over Christmas holidays spent in the Swansea valleys with my mum’s side of the family. They were never big drinkers, but if alcohol had been consumed then the whoops would become more frequent and much longer in duration. By 9 p.m. on Christmas Eve it was like hanging out with a bunch of malfunctioning but very friendly flight simulators.

As we know, consumption of alcohol speeds up our heart rate, widens our blood vessels, lowers our inhibitions and can cause significant damage to fixtures and fittings. It can help to put old arguments to bed, but can also help to create exciting new arguments, rich with potential and possibility. People start to fall over with theatrical flair. And at Christmas the British pursue all this stuff with vigour and enthusiasm; alcohol becomes the national anaesthetic, suppressing social awkwardness and allowing us to laugh at things that aren’t particularly funny. In 2004, some people with nothing better to do did a global survey and discovered that the British ratchet up their boozing at Christmas more than any of the other G7 nations. So we sit there, at the top of the pile, saying ‘cheers!’ to each other and wondering whether we should be feeling proud or not.

Stoptober and Dry January have become widely observed periods of abstinence, and they form a convenient bookend to what we might call Bender December. The counting of alcoholic units, a foggy concept to the British at the best of times, becomes even more erratic at Christmas. The quantities being slung back across the land make the whole idea of units seem a bit ridiculous, like measuring turkey consumption in micrograms. Quiet, unassuming relatives who barely touch booze under normal circumstances will suddenly be heard to say things like, ‘Ooh, don’t mind if I do’ or ‘Perhaps just a small one’, with a glint in their eye and a large empty glass in their hand. Later, they will do the can-can.

Hendon, Christmas 1976

I remember my mum and dad hosting a daytime drinks party in the run-up to Christmas. Those kinds of events were memorable when you were young, because you’d see adults getting drunk. You didn’t really understand it but you knew something unusual was up. This particular party had ended, and my dad, perhaps unwisely, was giving some people a lift home in the car.

He had a favourite crystal glass, for special drinks, on special occasions. In the course of tidying up, my mum, who was not a drinker but had had a number of sherries, picked it up and dropped it. It smashed into pieces. This was in the living room, and I remember her slumped over an occasional table, drunk and helpless with hysterical laughter, saying, ‘It’s his favourite glass, it’s his favourite glass.’ I’d never seen my mum lose it quite like that, and I remember feeling confused. I didn’t understand. If it’s his favourite glass, and you’ve broken it, that’s a bad thing, so why are you laughing?’

J. M.

In, say, March, or October, the casual suggestion of having booze for breakfast would prompt concerned relatives to plan some kind of intervention. But it’s different on Christmas morning, when orange juice is upgraded to Buck’s Fizz without any nudges, whispers or worried phone calls. This festive combination of mild depressant and vitamin C is one of a curious array of seasonal drinks that tend not to be consumed at any other time of year, with advocaat being another obvious example. We don’t show as much enthusiasm for eggnog as our American cousins (probably because we’re too busy laughing at the word eggnog) but we embrace advocaat – essentially eggnog plus brandy – warmly, perhaps because Warninks, the pre-eminent brand in the UK, has the decency to keep the mention of egg to the small print on the back of the bottle.8

“Just two more minutes, everyone. Just two more minutes.”

Back in the 1960s, the advertising slogan for Warninks ran ‘Eveninks and morninks, I drink Warninks’. This excuse definitely won’t wash with your family if they ask you why you’re drunkenly humping a footstool, and it seems extraordinary that an alcohol brand ever marketed itself as perfect for pre-lunch consumption. But a morning snowball (advocaat plus lemonade) is an acceptable part of the British Christmas, and, approached with care and caution, can make Christmas morning zip by in a pleasant haze. People can, however, go too far, and they do. Let this be a Warnink to you.

Twickenham, Christmas 1990

My family has always been quite boozy, and this particular year – I remember it was World Cup year, Italia 1990 – some friends of the family came to visit for Christmas Day. I went to the same school as the kids, and my dad was best mates with their dad, so they all came over in the morning and the adults started drinking enthusiastically. We had Christmas dinner at about three in the afternoon, but as soon as the starters had been cleared away my friends’ dad just fell asleep, face down on the table, snoring loudly. Nine of us were sat around the table. None of us could wake him up.

My dad, who has quite a rich baritone voice, started singing ‘Nessun Dorma’ [‘None Shall Sleep’!], which had been the big anthem for the World Cup that year. The singing got louder, and louder, but he kept on snoring, so we all joined in, all eight of us, in this big crescendo, because we’d heard the thing so often during the World Cup that we all knew it. And by the end, the big ‘Vincerò!’, everyone was laughing, but he still didn’t wake up so we had to move him to the sofa.

C. C.

Maintaining adequate stocks of Christmas alcohol can involve bottles of wines and spirits being moved between homes with the slick efficiency of a narcotics network. Unlabelled bottles of potent home brew can help to make up the numbers, and it’s quite likely you’ll find sloe gin in at least one of them. ‘Everyone round here gets very precious about their sloe berry spots,’ says Willow Langdale-Smith, who turns her local Leicestershire berries into booze and describes the results as ‘like a mince pie in a glass’ and ‘fucking phenomenal’. ‘Last year it was really tricky to find a sloe crop because some of the blackthorn bushes had been infected by a virus,’ she says. ‘When I found one that was unaffected, I quickly started filling empty dog poo bags with them – whatever I had in the car, it was a case of fill anything you’ve got.’

Making your own Christmas booze may be cost-effective and rewarding, but most people opt to march to the off-licence for a festive spending spree. Of all the drinks on offer therein, Baileys has manoeuvred itself into pole position as the UK’s Christmas favourite.9 We’ve been persuaded that chugging back a few measures of Baileys in December is sophisticated and slightly sexy, although after seven or eight of them you’ll be neither of those things. There was an advert for Baileys that ran for three or four years on British television during the 1990s, featuring a couple in a swanky hotel who were sufficiently emboldened by their Baileys consumption to start getting amorous in an elevator. While they did so, other hotel guests peered in enviously through its scissor-gate doors. Those guests represented us, a nation; we wanted a piece of hot Baileys action. ‘The advert was very aspirational,’ says Joe Cushley, who played one of the guests. ‘And they were evidently trying to sex up the brand. We were told to look into the elevator as if we could see the couple “performing sex”, but “not too much”. It was weird. I remember all the actors developed this primitive desire for free Baileys, but there was only one bottle there, which was the prop. Anyway, over the years the repeat fees for the advert were enormous, so I still raise a glass to Baileys to say thank you.’

The British alcohol industry has gone to great efforts over the past few decades to equate Christmas drinking with opulence, cream, comfort, cream, warmth, cream, elegance and cream. It’s a tried and tested marketing technique, from Harveys Bristol Cream (cream, button-back armchairs, roaring fires, ‘the best sherry in the world’) to Sheridan’s (cream, luxury, two-tone bottles, a yin-yang spout which produces a celebratory coffee-flavoured mini Guinness); from Cointreau (no cream, a French guy saying ‘ze ice melts’) to Stella Artois. All these drinks have one thing in common: in sufficient quantities, they can make you inadvertently swear in front of your grandmother.

Watford, Christmas 2004

On Christmas morning I didn’t feel well. My younger brother and I had gone out on Christmas Eve with the express purpose of getting as drunk as possible. We donned cheap Santa hats, made friends that no one should be making friends with, and wandered drunkenly around our sad commuter town. But as Christmas Day went on, our hangovers subsided. After dinner we decided to play a family game of Trivial Pursuit, and as the Stella kept flowing we all got into the game a little too much.

At some point I suspected that my aunt had made a minor infraction but picked up a ‘pie piece’ regardless, and I called her on it. She argued with me, and it began to get heated. I heard myself remind her that it was ‘a fucking pie slice question’, and immediately looked across at my 70-something, teetotal, devout grandmother who pursed her lips and glared at me. So yeah, I said ‘fuck’ in front of my nan on Christmas Day, and I was reminded of this for years afterwards. She died in 2015; I hope she forgot my foul-mouthery before she departed.

L. J.

Not everyone approves of swearing, and not everyone approves of drinking either. Despite Christmas drunkenness having become a well-established British tradition by Victorian times (and probably centuries earlier, it’s hard to say, our ancestors had a habit of losing the receipts), there are those who believe that Yuletide inebriation should never be encouraged. You may think that there’s little distinction between wishing someone a ‘Merry Christmas’ and wishing someone a ‘Happy Christmas’, but there’s subliminal messaging going on here. Queen Elizabeth II always says the latter in her Christmas address as a subtle hint that we should restrain ourselves. The former would apparently be like urging us all to go out and get smashed on whisky macs.

“Well, Angela has certainly come out of her shell this evening.”

You see the same disapproving tone in British tabloid newspapers, who publish pictures of debauched office parties spilling out onto the streets of provincial towns, like multiple stag dos happening at once, with a stern commentary about the declining morals of a once proud nation.10 Office Christmas parties might be unhealthy, they might even lead to a short spell in a police cell for the acting head of payroll who’s covering for Lorraine while she’s on maternity leave, but like them or not, they’re a part of our culture. In that fly-on-the-wall documentary of a typical British Christmas, Love Actually, Alan Rickman’s character states the typical approach to arranging one: ‘It’s basic, really,’ he says. ‘Find a venue, over-order on the drinks, bulk-buy the guacamole and advise the girls to avoid Kevin if they want their breasts unfondled.’ In truth, it might be better if everyone avoided everyone.

Croydon, Christmas 1990

I worked as part of a very dysfunctional team at a well-known shoe shop chain in south London. I remember that a goth ran the stock room, and he would write weird things on the shelves in permanent marker, like ‘I drink the vomit of the priestess’. The manager was this awful sleazy man, very large and sweaty, who had one of those wind-up clockwork penises on his desk.

We had our office Christmas party inside the shop. We brought in sausage rolls, alcopops and strong lager, and we started making turbo shandies. Things got a bit out of control, and the sales staff ended up locking the manager in one of those metal cages with wheels that you transport stock around in, and then forgot about him.

N. M.

The mismatch between the overwhelming demand for venues and a woeful supply shortage means that the office Christmas-party season now begins in October, before Hallowe’en, and ends in early February, by which time people are sick to the back teeth of Christmas and the whole event feels like a Fire And Ice-themed hallucination. But whenever it happens, it can quickly morph into a drunken splurge of emotion following a year of tension over rejected expense claims and overlooked promotions.

Manchester, Christmas 2009

At our Christmas party the CEO got blind drunk and passed out. The new and enthusiastic HR manager woke him up to ask him to make a speech. Everyone was saying, ‘Nooo, don’t’, but it was too late and the now-awake CEO grabbed the mic and started ranting about how terrible everyone was at their jobs, picking on people one by one. Understandably, some people objected, which further enraged the CEO, who then punched the director of operations before passing out again.

Another director said, ‘This is all your fault’, while pointing at the new HR manager, who burst into great drunken sobbing tears and everyone started shouting at his accuser for being cruel. Meanwhile, someone else tripped over outside while smoking a fag with his hands in his pockets. We sent him and his bloodied face to hospital in the same ambulance as two vomiting people who had alcohol poisoning.

J. D.

The many brands of painkiller, rehydration fluid and reflux suppressor that help people to deal with their hangovers tend to ramp-up their advertising campaigns in December, marketing themselves as the saviours of the gluttonous and the indulgent. Ridiculously, we tend to put these things very low down on our shopping lists.11 If, the morning after, you find a distressing absence of medication in the cupboard, there’s another option: hair of the dog. But while there’s plenty of dog hair to go around at Christmas, the evidence for it doing us any good is scant. We’re unlikely to benefit from seeking solace in whatever hurt us in the first place, and there’s an analogy I could draw here with a relationship I had in the early 1990s, but this isn’t really the time or place for that.

Despite its often unedifying after-effects, we have limitless affection for hot booze (and particularly mulled wine) in the run-up to Christmas. In A Christmas Carol, Dickens writes of ‘seething bowls of punch that made the chamber dim with their delicious steam’, and describes how cash-strapped Bob Cratchit manages to knock together ‘some hot mixture in a jug with gin and lemons’ in order to place a boozy gloss on the poverty his family were having to endure that winter. We live in a country where the temperature doesn’t drop below freezing that often, and most of us have central heating, but we still feel the need to heat up vats of dubious liquor, make it palatable with cinnamon, cloves and nutmeg and then ladle it into wooden goblets like a couple of Anglo Saxon revellers called Æthelbald and Eoforhild. The liquid might be billed as punch, mulled something-or-other, glögg (if you’ve got a thing about Vikings) or wassail (if you’re trying to lend your potent brew some historical legitimacy), but whatever it is, it gets you drunk more quickly than cold booze does. (I should add that I have no evidence for this theory other than my own weak anecdotal evidence. I did ask around, but it would seem that scientists have got better things to do than to test my unproven and probably incorrect theories about stuff that doesn’t matter, and who can blame them.)

Hot booze is a surefire Christmas money-spinner for the struggling British pub. The booze you use doesn’t really matter; in the same way that cheap white wine becomes more palatable the colder it gets, heating up red wine or cider can mask all manner of unpleasantness. Get a bag or two of mulling spices, wang it in a cauldron on the bar, stick a cardboard sign on the side featuring a carefree snowman and you’re quids in. The mark-up may be substantial and the liquid rather toxic, but as customers we can’t complain. That money goes some way towards compensating bar staff for their unenviable Christmas workload: dealing with revellers who a) can’t hold their drink, b) keep asking what you think of their jumper, c) order two rounds at once, including cocktails you’ve never heard of, and d) cause general havoc to a Christmas soundtrack until 1 a.m. Spare a thought for those who serve us the alcohol that will soon compromise our dignity. After all, we did ask them for it. They’re only obeying orders.

Peterborough, Christmas 1992

Me and my partner, who I lived with, went to the pub on Christmas Eve and he proceeded to drink much more than I did. Much more. I woke up relatively early the next morning, and sensed a steamy fug in the bedroom. It was a bit… cowshed-y. It was only when I got up that I realised he’d wet the bed. It was Christmas Day, the mattress was sodden, and worse, he was still absolutely hammered.

Initially he denied that he’d done it, which was ridiculous. Then he started to find it funny, but I was livid, and I told him that he’d ruined Christmas. He then went completely Basil Fawlty on me. ‘Right! I’ve ruined Christmas, have I? Well, in that case, why don’t I ruin Christmas completely?’ He marched down the stairs, over to the presents and unwrapped all of them, one by one, reading each label out to me as he did so. ‘So, Happy Christmas Uncle John, is it? Let’s see what’s in here, shall we?’ I just stood there, watching this drunken idiot ripping up paper. We’re not together any more, but I sometimes wonder if he remembers. It’s not something you’d forget, is it?

K. M.

We may all hope for the kind of soft-focus Christmas that we see in a Marks & Spencer advert, but alcohol can quickly turn from being an effective way of masking our emotions into suddenly becoming the bearer of great clarity. Situations that we’ve spent all year trying to avoid will suddenly be right there in the room, as honesty buttons are pushed and reality sets in. Drinkers find themselves doing things they really shouldn’t be doing, as booze traps them in their own worlds and causes them to unleash their own unique brand of embarrassing behaviour.

Weybridge, Christmas 1988

We always had big family Christmases. I’m one of seven, and we often had family friends over too. One Christmas when I was very young, I remember my primary school teacher turning up on the doorstep just as we were all sitting down for Christmas lunch. He had no trousers on. He was terribly apologetic about this, but he explained that he had no trousers with him either. My mum, who is very nice and would never have done anything other than invite him in, shooed him into the kitchen while she went upstairs to fetch some trousers for him. It was funny at the time, but of course now I understand that he was an alcoholic.

S. S.

Wandering trouserless in the streets isn’t remotely festive, and there are evidently people for whom the drunken revelry of Christmas is problematic. The sight of wobbly guys and gals making fools of themselves can be amusing, but festive boozing might be more of an issue for Brits than we realise. The December wind-down to Christmas can become rammed with social engagements, many of them defined by drinking; the week before Christmas Day can feel like a Carlsberg-sponsored assault course with a first prize of some more Carlsberg; oh great, thanks. And if we’re not drinking to have a good time, we might be having a few glasses of this or that to alleviate the Christmas pressures of gift buying, food preparation, logistical arrangements and coping with the unusual whims of our in-laws. Perhaps tragically, we use alcohol to help us spend periods of time with people who, despite being part of our family, we just don’t know very well.

‘These days I make much more of a thing of, say, putting out the reindeer’s food,’ says Lucy Rocca, who’s been dry for six years and heads up Soberistas, a worldwide community of people trying to give up alcohol. ‘I used to rattle through all that stuff, because my entire focus was on getting drunk. It took precedence over everything. Now there’s a different emphasis that’s more about revisiting my childhood, I guess. And I don’t know whether it’s because people are thinking more about their health, or because they’re resisting the cultural pressure to drink, but these days we get a lot more people joining us in the run-up to Christmas rather than waiting until January.

‘Drinking can absolutely be about twinkly fairy lights and glamorous parties and lovely cosy evenings indoors, but the people for whom it isn’t… well, they’re not often thought about.’

The thing is, it’s not always easy to let our hearts be light or, for that matter, put our troubles out of sight. Christmas boozing can assist with all that; it can help to clear out our mental in-trays and vigorously toe punt our worries into the New Year. But there, along with the dying Christmas trees, gym memberships and the dryest of dry Januarys, our problems will sit, waiting patiently for us to all turn up, regretful, dehydrated and wincing. Glass of Prosecco, anyone?

Carlisle, Christmas 2007

I had a traditional boozy Christmas Eve catch-up with some school friends in the pub. At closing time I went back to my mum’s, where I was staying in a small computer room. As soon as the lights went out things deteriorated pretty quickly. Trying to find my way out of the smallest room in the house at 3 a.m. was for some reason (and I still can’t fathom it) impossible, and I resorted to running my hands down every wall surface in a desperate attempt to locate a light switch.

Unfortunately, all I succeeded in finding was the top of a bookcase, which I proceeded to pull over and towards me, pinning me to the bed. Disoriented, confused, surrounded by books and, crucially, leathered, I was now completely stuck, and my mum was trying to prise the door open (which was forced shut by the bookcase) and wondering what on earth was going on. I called her a ‘stupid woman’ and told her to go back to bed. Those were the first words I said to her on Christmas Day.

D. K.