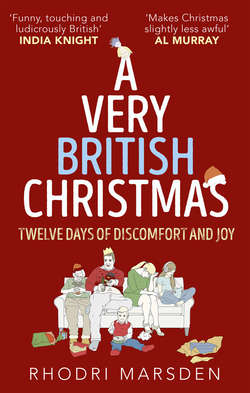

Читать книгу A Very British Christmas: Twelve Days of Discomfort and Joy - Rhodri Marsden, Rhodri Marsden - Страница 8

Ten Carols Screeching

ОглавлениеOrphans [singing]: God bless Mr B at Christmas time and Baby Jesus too,

If we were little pigs we’d sing piggy wiggy wiggy wiggy woo,

Piggy wiggy wiggy wiggy wiggy wiggy wiggy wiggy wiggy wiggy wiggy wiggy wiggy woo,

Oh piggy wiggy wiggy woo, piggy wiggy woo, oh piggy wiggy wiggy woo.

Blackadder: Utter crap.

Blackadder’s Christmas Carol, 1998

Musicians are fond of wistfully recalling the first song they ever wrote. I’m now obliged to reveal that mine had the title ‘When Christ was Born in Bethlehem’. The passing of time would have wiped this from my memory, but I’ve got a cassette here marked ‘Christmas 1980’ which I’ve just listened to while biting my knuckles with embarrassment, and there I am, this precocious kid, giving its world premiere to a battered cassette recorder. My family isn’t religious, so I don’t know why I got rhapsodic about Bethlehem and set those words to music, but I did. I wasn’t very imaginative; I didn’t throw in mentions of any jugglers, traffic jams, poodles or candyfloss, and just stuck to the accepted version of events, i.e. wise men, shepherds, a stable and a star. The tune is meandering and the poetry is poor; I rhymed ‘myrrh’ with ‘rare’, for Christ’s sake. (Literally for Christ’s sake.) If I’d written it today, of course, I’d have rhymed ‘myrrh’ with ‘monsieur’, ‘masseur’ or ‘frotteur’, because my vocabulary is now enormous.

‘When Christ was Born in Bethlehem’ never entered the liturgical canon, partly because my parents didn’t promote it with a letter-writing campaign, and partly because it’s up against a collection of tunes that’s deeply embedded in our national consciousness, thanks to centuries of vigorous bellowing. At this stage it would have to be a pretty catchy number to edge out the likes of ‘Ding Dong Merrily on High’, although ‘Ding Dong’ (as it’s rarely known) isn’t without its flaws. It was written in 1924 by an Anglican priest called George Woodward, who took a traditional French tune called ‘Le Branle de l’official’ and shoehorned in words with such brute force that it’s surprising the matter wasn’t reported to the police.

E’en so here below, below, let steeple bells be swungen,

And ‘Io, io, io!’, by priest and people sungen

Woodward repeated words in desperation and invented a couple of others to haul himself out of a poetic hole of his own making, before spreading the word ‘Gloria’ over thirty-five notes in the chorus, which is as audacious as anything Mariah Carey has ever attempted. In fact, on reflection, ‘When Christ Was Born In Bethlehem’ stands up pretty well against ‘Ding Dong’, and I’m going to stop being so hard on myself because I was only 9 years old.

It’s easy to sit here picking apart Christmas carols,12 but they’re likely to be the oldest songs you ever learn, so if you’re remotely interested in maintaining a connection with the past it probably behoves you to give them a yearly airing. Many of our most popular carols, such as ‘Good King Wenceslas’, ‘O Little Town Of Bethlehem’ and ‘Deck The Halls’, combine medieval folk melodies with words written in the mid nineteenth century, when the clergy was mounting a rescue operation to revive interest in a dying form. This was just as Dickens depicted Ebenezer Scrooge as threatening violence towards someone who dared to sing ‘God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen’ at his door; composers presumably figured that carollers should be equipped with some better material, and they set to work.

Carols such as ‘It Came Upon the Midnight Clear’, ‘Once in Royal David’s City’ and ‘We Three Kings of Orient Are’ were written from scratch at around this time, and within a few years a belting catalogue had been assembled that we still sing to this day. Some areas of the country take their carolling very seriously and have their own distinct repertoire. ‘Certain carols are peculiar to a small area,’ says Pat Malham, who’s sung local carols around South Yorkshire and Derbyshire for more than forty years. ‘For example, carols such as “The Prodigal Son” and “A Charge To Keep I Have” only seem to be sung in the villages of Ecclesfield and Thorpe Hesley. If you try to strike up an unfamiliar carol, the retort will come: “We don’t sing that one here”!’

Cornwall, Christmas 1981

I remember my dad taking us to midnight mass. We weren’t a church-going family, but me and my brothers thought it would be a wheeze to stay up singing carols past midnight and deliver one in the eye to Santa. But we were wrong, it was nothing of the sort. It was deathly dull, with carols coming all too infrequently during a very long, sombre sermon.

I did, however, get to hear my dad sing ‘O Come All Ye Faithful’, right out loud and with proper conviction. I don’t ever remember him making any other musical forays, so it was an unfamiliar sound, but it came across as both joyful and triumphant. Even to this day, the climax of ‘O, come let us adore him’ can reduce me to shoulder-shaking sobs of nostalgia. I don’t think I ever went to church, nor heard my dad sing, again.

J. T.

Carols can have emotional resonance for many of us, but the grouchier members of the community will always resent the brutal sonic assault represented by ‘Away In A Manger’. Over a hundred years after the publication of A Christmas Carol, the novelist C. S. Lewis published an essay called ‘Delinquents In The Snow’, where he, too, stated his distaste for ‘the voices… of boys or children who have not even tried to learn to sing, or to memorise the words of the piece they are murdering. The instruments they play with real conviction are the doorbell and the knocker… money is what they are after.’ Thankfully we’re not all as mean spirited as C. S.; some of us give carollers the benefit of the doubt, and see them as nobly extending an ancient British tradition of wassailing and mummers’ plays, rather than assuming that they’re about to vandalise our car.

My choir does carol singing every year. Christmas doesn’t feel like it’s started until I’ve done it. We sing the same carols in the same order and the same things always go wrong. We only sing for about an hour, but you can get very cold in that time, so a bit of mulled wine (provided by a local shopkeeper) with a decent slug of brandy is part of the whole experience.

One year some builders pulled up next to us and played techno out of their van. Another year someone turned all the lights out in their house when they heard us singing. But the reception is generally positive. We sing under lampposts rather than at people’s doors, and send whichever teenage child has been dragooned into helping out up to the doors with a bucket. There’s a certain amount of ‘I don’t have any change’, but people have been known to follow us down the street after we’ve left their patch in order to donate. You can see yourself making people’s Christmases.

J. L., London

In keeping with oral tradition, carols find themselves morphing and changing as we mishear words and get things wrong. For example, in ‘Silent Night’, Mary is not a ‘round, young virgin’; no, everything just happened to be ‘calm and bright’ around ‘yon virgin’, i.e. that virgin who’s sitting over there. In ‘Good King Wenceslas’, Wenceslas has three syllables, so he didn’t ‘last’ look out, he just looked out. (Bear with me, I’ll stop being angry in a second.) It’s not your ‘king’ you’re wishing a Merry Christmas, it’s your ‘kin’, i.e. your family, and in ‘God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen’, they’re not merry gentlemen you’re asking to have a rest,13 they’re gentlemen who ideally would ‘rest merry’, i.e. take it easy, have a good time, chill out, because after all, in the words of Noddy Holder, it’s Chriiiiiiiistmas.

“Unprotected sex with strangers, fa la la la la la la la la…”

More deliberate liberties are taken with other carols. A friend of mine tells me the story of her former headmistress who, for some reason, decided that the three verses of ‘Away In A Manger’ were insufficient and wrote a fourth for the school to sing. It ended thus: ‘the mouse squeaked in wonder and jumped from the corn, and lay by the manger where Jesus was born.’ (No, I’ve no idea either.) Words get changed for the purposes of mild amusement: the late 1930s saw kids address the weighty topic of the abdication crisis with ‘Hark the herald angels sing, Mrs Simpson’s pinched our king’; there’s the perennial favourite of ‘While shepherds washed their socks’, and in one version of ‘We Three Kings’ the Magi travel to Bethlehem in a taxi, a car, and on a scooter while beeping a hooter and either wearing a Playtex bra, or smoking a big cigar. That’s one hell of a welcoming committee for a baby boy.