Читать книгу Secrets of a Gay Marine Porn Star - Rich Merritt - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

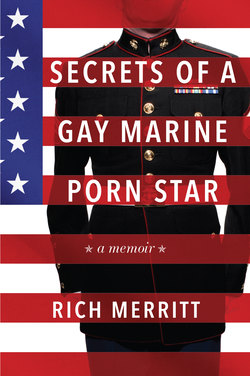

1 THE MARINE WHO WAS ALSO A PORN STAR

ОглавлениеI didn’t expect the article to be a story about me. I honestly didn’t. I thought it was going to be a story about my friends, about this group of guys and how we all stuck together, and how we always tried to be there for each other.

The New York Times Magazine had assigned a young, freelance writer named Jennifer Egan to write about what day-to-day life was like for those of us in the military living under the “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. About how we felt trapped in this kind of no man’s land. The article would reveal how we were not necessarily a part of the military community because we were gay—there was always that distinction. Yet we were not completely part of the gay community either, because we were in the military. We were caught in the middle. But at least we had each other. That’s how we all felt and that’s what I hoped the story would convey.

In researching the story Jennifer contacted the Service Members Legal Defense Network (SLDN), an organization out of Washington which provides free legal services for anyone in the military facing an investigation, charges, or any problem with the “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. Jennifer asked SLDN for assistance in locating military people who would be willing to talk about their experiences. Since southern California has a heavy concentration of military personnel, Jennifer decided to conduct some interviews in San Diego.

I was an active-duty Marine stationed at Camp Pendleton, just north of San Diego, and had been writing op-ed pieces for the Navy Times. I had recently written this one piece which suggested that “Don’t ask, don’t tell” should be repealed. That caught the attention of SLDN. I had also been previously introduced to Tim Carter, the co-chair of the organization. Tim contacted me and said, “We’re going to put a New York Times reporter, Jennifer Egan, in touch with you; is that okay?”

I said, “Sure.” I thought it would be great to be part of a story that would reach so many readers.

“This journalist is looking for a model of the military,” Carter added. “A poster child.”

I wasn’t exactly sure she’d find that representation in me but I thought there was a good chance she’d see that image in one of the people I planned to introduce her to. I was aware, however, that a “poster boy” was at least a part of who I was. At that time I had attained the rank of captain and I was a commanding officer, the most sought-after position in the Marine Corps. My assignment just before I became a battery commander had been a general’s aide-de-camp, a very high-profile and demanding position that gave me a lot of connections I could use down the road when it came time for promotions and other selections. So the trustworthy, hardworking, reliable Marine was certainly one role I fit into.

The romantic homosexual in a loving relationship was another. I had already gone through my wild period, or so I thought. By now I had been with my partner, Brandon, for almost three years and I was trying very hard to make a committed relationship work.

But we all go to bed with our secrets. Let’s face it, most of us are many personality types dwelling in one body, showing various sides of ourselves to different people as we see fit. I was aware that the Times was not digging for the sordid lives that many of us lead in one way or another. They were looking for the golden boy, the guy you always imagine when you hear about gay men in the military. So I thought, Fine, I’ll present them with that image of myself.

At the time I did not realize just how expert I was at slipping on different masks. My background had trained me well for projecting whatever image was expected of me. My deep dark secret, the thing that would be considered part of my “sordid” hidden life (and the issue that would set in motion the unfathomable ordeal that would soon follow) was the fact that I had appeared in porn films four years earlier. Eight of them. As hard as it is to believe now, at the time I really didn’t think that my brief fling with the porno industry was pertinent to the story because, as I said, I had no idea the story was going to focus on me. All I kept thinking about was, Finally someone is going to tell our story—what being gay in the military is like for us.

There was a precondition that the interviewees for the Times story were to be anonymous. Jennifer explained that the New York Times would not give us fake names, but that we could go by one initial. We could pick whatever letter we wanted. I decided to use my real initial. In the article I would be identified as “R.”

I went down to Jennifer’s hotel in Coronado to pick her up, and she and I bonded instantly. We had rapport. She’s very quiet, somewhat timid, but a genuinely warm, receptive person. Plus, my longtime reserve had me longing to be forthcoming about so many things. I had so much inside of me, all these ideas and emotions bottled up about what living under this policy was like. I started spilling my guts out. Yet, the whole time I was talking to her, in the back of my head was the porn thing. I could almost hear an audible debate going on between my opposing selves. It was as if one part of me was saying, “I’ve been in porno movies.” And the other was saying, “But don’t tell her, because if you do, you won’t be part of the Times story.” That was the part that won out.

Soon after our interview, I set up a dinner for Jennifer to meet about twelve of my military friends at a house in San Diego. The fact that she witnessed firsthand how we were a support system for each other is what planted in my head that the story was going to be about all of us. I had no idea how much of the focus of the story would be on me and how much of her article would talk about my friends. I was completely unaware of what Jennifer would use or how I would be portrayed. Apparently that’s pretty common in journalism—the subject or subjects of the story aren’t briefed on the work-in-progress.

Maybe I should have picked up clues. As I’m writing this, things pop into my head: I recall that Jennifer came back a few weeks after the initial interviews and for the first time she brought up the issue of photographs. SLDN hadn’t said anything about pictures. Later, when they found out, I could tell they were upset. Pictures would be too dangerous, they said. But at the beginning, they just said “cover story.” I don’t know how they could have thought this could be a cover story without photographs. But Jennifer asked, “What are we going to do about the pictures?”

Most of the people who had participated in the interview were not willing to have their picture taken, even with their faces hidden. I, on the other hand, said to Jennifer, “You’re going to cover my face in the photo and call me ‘R’ in the article? Then, fine. Of course I want my picture taken.” But only two other guys, another Marine officer and a Navy officer, agreed to a photo session.

A few weeks later photographer Matt Mahurin came out to take the pictures. We spent several hours with him. He took some off-duty photos of Brandon and me a few days later. But his first shots were of the three of us officers in uniform taken in Balboa Park. For the pictures of us in uniform, at one point he posed the three of us in a line, saluting. I instinctively felt it would make a fantastic photo and envisioned it on the cover.

The other Marine officer Matt photographed was my very good friend, who was nicknamed “Bossy.” Bossy and I were both decked out in the full Marine dress blue uniform. Bossy, however, had forgotten his white gloves. Matt wanted a photograph with our gloves on, so I gave one glove to Bossy, put one on myself, and then Matt posed us close together side-by-side in a shot where only our gloved hands were visible.

Matt then said he had to get some solo shots of me, although he didn’t say why. He came up with the idea that I should salute, and that that the salute should cover my face. He lay on the ground and took a shot directly up. I thought he was catching only my chest, shoulders, and head.

A homeless vet walked by our little group in the park. “Cap’n,” he said, “your salute is all fucked up.” He was right. My arm was deliberately canted so that my face would be completely covered. As salutes go, it was all fucked up.

“We know what we’re doing,” Bossy said dismissively. The vet mumbled something about being a retired master sergeant and never having seen such a fucked-up salute on an officer and walked away. We resumed the photo shoot before the sunlight disappeared.

Matt had read a rough draft of the article and during the session someone asked him what the story was about. “Well,” he replied, “the story’s about Rich and his friends.”

That startled me. Oh my God, I thought, this story is about me? An eight-thousand-word article is a New York Times cover story about me!

On one hand, it was exhilarating. But now more than ever the porn thing was haunting me. I had an impulse to call Jennifer and tell her not to write about me. Obviously I didn’t give in to that urge. Maybe it was ego. I had spent so much of my early life living up to the expectations of others and here, just maybe, now it was my turn. And it was a subject that I was passionate about, something that was pertinent to my life and thousands of others. I knew that it would help a lot of people—I was desperate to be a part of it.

A few weeks before the story appeared, the fact checker called and started asking questions. I was on the phone for almost an hour and I started to feel uneasy. Afterward I made a list of things that she had asked about. By the time I was finished I thought, “I’m toast!” There were key things I had told Jennifer that made me completely identifiable: General’s aide. Commanding Officer. Captain. Southern California. From a Southern religious family. Had done overseas tour. Had been on ship. Initial “R.” It wouldn’t be difficult to connect the dots. Anyone who knew me and read these things, would know I was the “R” in the story.

The magazine was scheduled to come out, so to speak, on Gay Pride Day. I still had six weeks left on active duty after that. They wouldn’t wait for me to be out to publish it because, obviously, the New York Times doesn’t change its publication schedule for a personal issue that arises. I felt that I would be safe because I had submitted my resignation already. I knew the Marine Corps would rather just let it slide. They would rather just let me slip quietly out the door rather than make a big issue out of this. Yeah, the Times cover story was going to be a big deal, but it would be a much bigger deal if they came after me. I was counting on that.

Two weeks before the article appeared, I was in Los Angeles for an SLDN pool party/fund-raiser. At this party I met a freelance writer named Max Harrold. By now, there was a definite buzz in the air about the upcoming New York Times Magazine article. Max approached me, “This sounds really fascinating,” he said. “When do you get out of the Marines?”

I told him that I’d be officially out in the fall. I could almost see the wheels turning in his head. “Can I do a story on you when you get out?” he asked eagerly. “We can reveal your identity and I’m pretty certain I can sell it to The Advocate or one of the other magazines.” I liked the idea as long as I was safely out of the Marines. I agreed that as soon as I was officially out of the service, I would give him an interview.

As time grew closer to the date of publication of the New York Times story, my immediate concern was that the Marines would find out I was the “R” from the story while I was still in the service. I tried to talk myself out of my fears. I kept telling Brandon, “Oh, there’s nothing to worry about. They don’t say who I am.” But, although I hadn’t seen an advance copy and I had no idea what was going to be in there, I had a nagging feeling the Marines would find out who “R” was.

Saturday, June twenty-seventh fell during Gay Pride weekend in Los Angeles and I knew we’d be able to get an early copy of the Sunday New York Times there. As Brandon and I were driving up, I was well aware that it was already on the stands in big cities. I can’t even describe the excitement. The anticipation. The fear. The anxiety. All of that.

We finally got up to LA and, without stopping, went directly to see my friend Tim Carter. The first thing Tim said is, “Rich, you’re finished. You’re history.” He handed me a copy. The first surprise was the cover. There I was saluting—alone! All the while, I had been thinking they were going to use the photo of the three of us standing in a line.

Tim was beside himself. “Look, this is you!” he said immediately. He started talking about General McCorkle, the man I had been the aide to, “You don’t think that he’ll be able to look at this and see that it’s the side of your head?”

I looked at the cover very closely. You couldn’t see my face but you could see everything from my ear back. I thought I was unrecognizable. “No,” I said to Tim. “I don’t think you can tell that this is me. For one thing, I look six feet tall. I’m only five seven.”

The illusion about my height wasn’t the only abnormality in the photograph. At first I didn’t notice the glaring defect. A friend and fellow Marine who was also quoted in the article called me the following day.

“You’re wearing only one glove!” He exclaimed. “What were you thinking?!” He was right. I hadn’t noticed it, but there I was…a one-gloved Marine. I was out of uniform, the worst mistake a Marine can make. Well, almost. Fuck, I thought. I forgot to get the glove back from Bossy. Besides, I thought Matt was only taking the shot from the chest up! My ungloved left hand was visible. What was worse, my left thumb wasn’t along my trouser seam as I had been trained for so many years to stand at the “position of attention.” If it had been, my bare hand wouldn’t have been visible. I had been concentrating so hard on covering my face with my right hand, I hadn’t paid attention to my left.

But tonight I didn’t notice the glove issue—I was too focused on the content of the story. I read it quickly and admitted, “Yeah, they’re going to know it’s me.”

Jennifer started the article off by talking about me, later weaving in the other people. But she kept coming back to me, to my story. Still, I thought the piece was beautiful. I felt Jennifer had captured everything that we revealed to her. She had grasped the situation fully. There are a lot of issues about gays in the military that people don’t think about. For example, she really understood the suffering of my friend, Jim. Jim is the type of person who feels emotions very deeply, even if he doesn’t always show them to everyone. Jennifer, being perceptive, really had empathy for him. In the article, it was clear that she sensed how painful living in secret was for him. Jim told her the story about being out to sea on the USS Constellation. The fighter jets can’t take off and land from the deck of an aircraft carrier when the ship is in the port of a crowded city like downtown San Diego. The ship sails way out to sea and then the jets take off from their air station on land, fly out to the sea and land on the deck of the aircraft carrier off the coast of San Diego. The same is true coming home from a deployment at sea. They always let the fighter pilots with wives and fiancées and girlfriends fly off early, while the ship is way off the coast. Flying back to the air base is a really big deal—there’s always a large crowd and huge celebration waiting to greet the returning pilots.

Jim is one of the most senior guys in the squadron—and he’s got a lover back home. Yet, he has to ride into the port on the ship because he doesn’t have a wife or a fiancée or a girlfriend. That really affected him. Jennifer picked up on that and she really told those stories remarkably well.

She also understood that it’s not enough to be neutral. There’s no such thing as “Don’t ask, don’t tell.” You cannot be sexually neutral. She powerfully conveyed that in the article. She revealed how I would have to take fake dates to military functions. One gay Marine officer friend, the same observant friend who caught the “one-glove faux pas” called them “stunt babes.” She put that quote in there and it was fantastic that the general public was finally reading about these kinds of situations.

After I finished the article, I also recall having a feeling of loneliness. I hadn’t seen myself as alone before, because the gay military community is very closely knit. But Jennifer, in her poignant way, had portrayed an image of me, and ultimately of all of us, as being isolated and lonely. She used me to convey the idea to her readers that “Don’t ask, don’t tell” means that gays in the military can’t trust anyone, not even other gays in the military. All it takes is one person to get caught and questioned or to get angry or jilted and turn the whole group in. I hadn’t seen that because I hadn’t wanted to see it. But I really was lonelier than I had realized.

I couldn’t worry about the loneliness, however, because the reality of the possibility of my “sordid secret” came crashing down on me. Of course Brandon already knew that I had done eight pornographic films—meeting him was the reason I stopped. But I wanted to reveal it to someone else who could help me with the legal problems should the worst-case scenario happen. I began to feel I might really be in danger. Once the Marines found out this was me in the Times story, they might do an investigation. An investigation might lead them to my porn past. If they found out about that I could go to the military prison at Fort Leavenworth for many years. I panicked.

That night, I said to my friend Tim, “I’ve got to tell you something.” That’s when I told him that I had done porn. He nodded saying that his partner mentioned that he had seen me in a video but Tim had refused to believe it was me.

I went to work that Monday. The whole drive up I felt paranoid. Freaked out. I had no idea what the reaction among the Marines would be. But, to my relief and surprise, nothing out of the ordinary happened that day. Not a single word was said about the article, which, in all honesty, brought more of my emotions to the fore. Along with the fear of being discovered was my absolute pride at being part of such a groundbreaking story. The world didn’t know that I was “R” yet, but I kept thinking that in a few months, when the freelance writer Max Harrold wrote his profile on me for The Advocate, everyone was going to know.

Tim Carter, fearing the worst, advised me to clean everything out of my apartment that was remotely gay-related. Monday evening, I boxed up all of my books by gay authors, all of my photographs of my friends and me at gay pride festivals and parties, my address book, my computer and everything personal in nature and drove them up to Tim’s, where he stored them in the basement. If the military searched my apartment, the investigators would think I had no friends or any kind of a personal life at all. I’m so glad I live in a free fucking country, I thought as I hauled my personal life up to LA.

Tim sent an e-mail to everyone in my computer address book. Looking back, it was probably more cryptic than necessary. It said something like, “Our friend is okay, but do not try to communicate with him.” The problem is, most of my friends didn’t recognize Tim’s e-mail address. They were more afraid after getting this e-mail than they were before. Suddenly, I was without e-mail, without any of my personalized possessions, without my computer, and I was too afraid to call anyone, out of fear the military was tapping my phone. This truly was a terrifying time.

Meanwhile, a friend who had connections at the highest levels at Marine Corps headquarters got a message to me saying that there were debates about what they should do with me. There were two generals named Van Riper, brothers I believe, who, it was said, wanted to crucify me. General Krulak, the commandant of the Marine Corps, the number one general, was a Holy Roller, a Bible thumper (which I once was), and he worried me the most. I know how that mind-set works: anything to further God’s will is justifiable. But apparently in the long run he was political enough to realize, “It’s better to just let this go.” It was this opinion, I feel, that eventually won out.

Back at my battalion, a couple of weeks after the article, I was talking to my commanding officer. We were having one of our daily talks about battalion business and at the end of the discussion he abruptly said, “Oh, and there’s something else I need to talk to you about.” I had a feeling of what was coming. I just looked at him.

He pulled out a black-and-white photocopy of the Times article. I could see that there were highlighted portions. “This is an article that was in the New York Times Magazine about a gay Marine who goes by the initial ‘R’,” he said. “There are a lot of people who think this is you.”

Before I could say a word, he held up his hand. “I’m not asking if this is you,” he said firmly. “In fact, I already checked with the base legal section and I can’t ask if this is you. And quite frankly, I don’t give a damn if this is you. If someone gives you a problem about this, you come see me about it.” And then he added, “As long as you’re in the Third Marine Aircraft Wing and General McCorkle is the commanding general, you don’t have anything to worry about.”

The Marine Corps was taking care of me.

SLDN, in their fund-raising literature summing up their accomplishments for 1998, described how they intervened to prevent a witch hunt at Camp Pendleton after the Times story. I’m sure they did, but at the time, I wasn’t aware of any efforts they were taking on my, or anyone else’s behalf. Maybe they were instrumental in keeping me out of trouble at this point. I don’t know. But I can say one thing with authority, while I was living it, I felt like I was on my own.

A few days later, the lieutenant who worked closely with me, the executive officer of my battery, approached me. He also showed me a copy of the article and said all the Marines in my command were discussing it. “Is this you?” he asked.

“I’ve seen this,” I replied simply, “Do you think whoever that is could answer that question honestly without getting in trouble?” He just shook his head as if he understood. I was his boss, but we were good friends, as good as a commanding officer and an executive officer could be in that situation in the military. He was disturbed because in his heart he knew it was me. Yet I had the gut feeling that he was more upset because of the fact I hadn’t confided in him.

Every Marine feels a loyalty to the Corps that people who aren’t Marines can’t understand. I could see how a Marine would read that story and think that I had betrayed the Marine Corps. I had gone outside the ranks and talked to a reporter about all of these very personal and hidden issues. Even though I had done that, I was not an exception to this sense of loyalty. The whole time I was talking to Jennifer—and my friends were talking to her—we made sure that we painted the military with dignity. We loved the military. We loved what we were doing. We just didn’t like this one law because it forced us to live our lives counter to our military values of honor, courage and commitment. That’s totally what we conveyed to her and that’s how she wrote it. I pointed that out to the lieutenant.

But after being approached by both my commanding officer and my executive officer, I realized, Everyone knows that it’s me being quoted in the article. I still had a month to go. And, let me tell you, that month was hell. Every day I came in and every day everyone was looking at me as if they had cracked the code and identified me as the impertinent “R.”

I had been personally invited to General McCorkle’s farewell party and, because I had such deep respect for him, I had no intention of letting my fears keep me away. However, I planned to arrive late, sneak in, say hello to him and his wife, Kathy, and then make a hasty departure. The party was in full swing with many of the officers of the Third Marine Aircraft Wing—the Third MAW—present when I entered the front of the Camp Pendleton officers’ club. Having been his aide for a year, I should have known that General McCorkle would be late, but I was too nervous to think about that.

As I stood in the doorway to the room where the party was being held, trying to find a discreet spot to slink off to, I heard a familiar, deep voice booming in the hallway behind me.

“Captain Merritt! How the hell are ya?” The general shook my hand as every eye in the room turned to watch his entrance. But because of where I was standing—absolutely frozen—they all saw me first. I was blocking their view of the general. I don’t know how many of them knew that I was the gay Marine officer from the Times story—probably all of them, maybe none of them. But I felt like Scarlett O’Hara in the scene from Gone with the Wind, when Rhett makes her go to the party wearing a slutty-looking dress after everyone in Atlanta has found out about her “affair” with Ashley. Scarlett enters the room and a hush falls over the crowd as they all stare at her with contempt and disbelief. No one said a word, however, at least not to my face, and this party ended with General McCorkle wishing me the best of luck with my law career. Just as Melanie was so gracious to Scarlett.

On my last day in the Marines I had a change-of-command ceremony. This ceremony represented me handing the command of my battery over to another captain. Before the ceremony my lieutenant took me aside and said, “Sir, everyone thinks you’re going to ‘come out’ today.” It sounded like he was accusing me.

I immediately went over to my first sergeant. “I don’t know what people are saying,” I told him very quickly, “but I would never do anything to disgrace this battery. This last year and a half hasn’t been about me. It’s been about the men and the Marines and this battery and I’m not going to do anything to diminish that or say anything to diminish that.” He just nodded. I think he was glad that I told him that.

Just before the ceremony, I checked my military e-mail account one last time. A gay acquaintance at Third MAW headquarters had just forwarded me a note that General McCorkle had sent to all the commanding officers in Third MAW the Friday before the Times story came out. The Times had sent an advance copy of the article to the Pentagon, which in turn forwarded it to the West Coast generals. In the e-mail, General McCorkle advised all the squadron commanders that any issues pertaining to this story were to be referred to the legal officers immediately. It confirmed my suspicion that the article really was a big deal at the highest levels. I was also angry because, while the Times had sent the Pentagon an advance copy, they hadn’t even bothered to give one to any of the participants in the story.

A few of my gay military friends came to the ceremony, but most stayed away out of fear of being associated with me. At the ceremony fifteen months earlier, when I had taken command of the battery, many gay servicemen had attended, proud to see one of our own taking command. Now, I felt like a pariah. I also found out afterwards that my men were trying to figure out which one was Brandon, my boyfriend who had a feature role in article. They mistakenly assumed a fellow Marine, Bossy, was my boyfriend, choosing him as the “gayest” over my real boyfriend, Brandon.

After I was officially out of the Marines, I was free to “come out” as the man behind “R” and I did my long-awaited interview with Max Harrold. A photographer came to my condo to take some photographs and, unlike the Times photos, these pictures would show my face.

Max Harrold took me to the offices of The Advocate and I met Judy Wieder, the editor in chief. It was a very friendly meeting. The article hit the stands in the December issue of The Advocate. George Michael was on the cover because he had just come out after getting busted for beating off in the park.

The article identifying me as the Marine from the cover of the Times was a two-page spread with a big photograph of me wearing my USC T-shirt with my sleeve rolled up showing my USMC tattoo. Unlike the New York Times Magazine article, however, I didn’t like this story. Max was incorrect about several things. He also left out several really interesting tidbits. I remember I wrote to Jennifer Egan fuming, “I just can’t believe this.” I pointed out all the things he got wrong.

She replied, “You just have to let this stuff go.” I didn’t realize how relevant that piece of advice would soon become.

Things were starting to happen very quickly. Jennifer told me that the Times wanted to do a feature story on Brandon and me, and she would be the writer. She said this was rare, the paper and the magazine rarely do crossover stories like this. Soon after that she conveyed the happy news that her magazine article had been nominated for a Pulitzer. I was incredibly excited.

Next, the Los Angeles Times called requesting an interview. They did a story on me that also included photographs. It was all really thrilling. People were aware of who I was. “This is the New York Times cover boy!”

And then, just as it was getting bigger and bigger, the bubble burst.

Shortly after Christmas I received a phone call from John Erich at The Advocate. He informed me that one of his readers, a man to whom I had been introduced by a mutual friend years before, recognized me from my pornographic videos. Now the editors wanted to know if it was true. Was I the model from the porn videos?

I was stunned. All I could say was, “I don’t have any comment. Let me get back to you.” Before I could hang up Erich said, “Well, we’re going to do a story.”

I immediately called SLDN and they in essence told me, “We have nothing to do with this—SLDN has nothing to say about this.”

I thought, Oh great. I’m being abandoned by these people. I had done the story partly for them. I had put my neck on the line—not to mention that I had helped raise a lot of money for the organization. Now I felt as if they were washing their hands of me.

Panic-stricken, I called The Advocate back. “I don’t understand why you’re doing this story,” I said indignantly. “It doesn’t help anyone. If it’s a lie, you’re going to get sued for libel. If it’s true, what good does it do? I don’t understand why you would do this.” My argument didn’t do anything to sway them.

After I realized that they were going to go ahead with the story, the worst part was knowing how this would affect Jennifer Egan. I had trusted her completely. She had placed her trust in me as well, and she rewarded me with a beautiful article. Sure I spilled my guts to her, but I hadn’t spilled all my guts. I had chosen what I wanted her to hear.

I called Jennifer and told her. I could hear the hurt in her voice. I sensed that she was feeling as if I betrayed her. But all she said is that she would get back to me. Soon after, she telephoned. Obviously the new feature story was off. And now the Times was going to have to print something about my past, which they did shortly thereafter—on page A-17: GAY MARINE IN TIMES ACTED IN SMUT FILMS.

Brandon and I kept thinking that maybe The Advocate wouldn’t make such a big deal out of it. Indeed, the next issue didn’t have anything about it at all. I breathed a sigh of temporary relief. Jennifer called me feeling the same way. “Maybe they decided to drop the story,” she said. I could only hope.

But two weeks later, on a Sunday, I received an e-mail from a friend of mine in DC. The e-mail simply said, “I just saw The Advocate! Fuck ’em.” So I knew something was coming. Yet no one was talking to me. The silence was deafening.

Monday night I came home and Brandon said, “Tim Carter just called—You’re on the cover.” Oh my God. Now I was identified as THE MARINE WHO WAS ALSO A PORN STAR. I was just mortified. How was I going to deal with this?

Everything I struggled to accomplish in becoming a Marine would now be questioned. All the good things I had hoped would come out of Jennifer Egan’s article would be stained. Everything that had come before would now be put under a microscope. My goals, aspirations, my very character, were all about to come under major scrutiny because of two completely separate parts of my life that would soon be connected forever: the fact that I had been a Marine and the choice I made to appear in porn films. Now even I questioned my choices.

I didn’t know I was gay when I joined the Marines, or rather, I hadn’t consciously admitted I was gay, even to myself. My fundamentalist Christian teachers had taught me that homosexuals were evil people; therefore, I could not be a homosexual. Occasionally, I had sexual thoughts about other men, but because I could not be gay, I assumed most men were just like me and also had these thoughts. I was adept at mental gymnastics.

I joined the Marine Corps for the same reasons most people join the Marine Corps: I loved my country and wanted to do my patriotic duty. I also needed money for college, and I joined in 1985, just after Congress had just passed the new GI Bill giving tuition assistance to men and women who had completed their service commitment.

Subconsciously, I felt deficient in my masculinity and wanted a boost to my manliness. I also wanted to be around a lot of men. Wanting to be around a lot of men is not a homosexual desire; many heterosexual male Marines prefer to work in an all-male environment. For me, however, my desire to be around men was both sexual and nonsexual.

I also wanted a sense of belonging, a sense of being part of something larger than myself. I wanted to be a part of “The Few, the Proud.”