Читать книгу Secrets of a Gay Marine Porn Star - Rich Merritt - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2 THE GOOD SON

ОглавлениеWhen people are trying to get to know me, asking me questions, attempting, I guess, to find out why I made the decisions I’ve made and what led me to become the man I am—I look back over my childhood. At the time, nothing seemed all that unusual to me. It was all I knew. I had nothing to compare it with. But reviewing my life as an adult I can understand—so clearly—that my decisions, my inhibitions, my exhibitions, the person I am today, all have their roots in that small Southern town where religion was such an integral part of my existence. A place where I always tried so hard to please and live up to the expectations that everyone had for me—my parents, my family, my teachers, God, but most of all myself.

I was born in the early fall of 1967, just at the end of the fabled “Summer of Love.” The “Summer of Love” was as foreign to my birthplace as the Haight-Ashbury or Greenwich Village. I was born at St. Francis Hospital in Greenville, South Carolina, appropriately beginning my existence at a church-affiliated hospital. I always perceived my upbringing as middle class, now I think it may have been lower middle class.

To get to my house, you went ten miles south of Greenville and took a nondescript exit off the freeway onto a narrow, winding, rural country road. On a hill off the road, there was a big plot of land that my granddad had purchased years before. As any Southerner will tell you, family is of utmost importance. Grandpa Merritt’s house was there, and right next to it was our house, and right next to that was the house of my aunt and uncle. Our house was small; my grandpa built it in 1963 for my parents. We had a big front yard and a driveway, which we shared with my aunt and uncle. There was an extensive wooded area behind our houses that sloped steeply down to a winding river. If you kept on going down the road another mile you would come to a little town called Piedmont built on the banks of the Saluda River.

At the time I was born my father was working for Duke Power as a meter reader. Soon after I was born my mother went to work doing bookkeeping and secretarial stuff for a big chemical conglomerate.

I loved my mom. She was beautiful and tender and we were very close but sometimes, it seemed to me, she had trouble expressing herself. For as long as I could remember, I was always, always, always trying to do little things to make her proud of me, but she never seemed be able to satisfy my hunger for approval. She did feel proud of me for many things—my sensitivity, my thick hair, my thoughtfulness—but she wasn’t always able to express it. Or maybe I just needed to hear more than she was able to give.

In the mornings, before my mom left for work, she would take me to Momma King’s. She was my babysitter and the one person in life to whom I could do no wrong. She spoiled me, buying me the kind of apples I liked, making me pinto beans for lunch, and things like that. To this day—and she’s in her late eighties—when I visit her she says, “Richie, do you remember when you were two years old, I was dusting the light, standing on that footstool, and you came in and said, ‘Momma King, be careful. Don’t fall, you’ll hurt yourself.’ At two years old you were the most thoughtful little boy.”

And that’s the kind of thing my mom would never say to me. She would never point out that I was considerate—because she wanted me to be even better. Yet Momma King made me aware of all those little things I did right. Things like that stand out in my mind because they were so important to me at the time.

One sunny October morning in 1970, I was staying over at Momma King’s and I remember walking across her driveway as Daddy pulled up in his 1960 black Ford Falcon. Momma was in the passenger seat, looking radiant and lovely, as every mother should appear to her three-year-old child. My mother always looked that way to me. She was holding something across her chest.

Momma King had already informed me that my parents would be bringing my new little baby brother home from the hospital that day, but I was unprepared for the sight. I was overwhelmed. I had seen Mom hold babies before, but not one of her own. Seeing her sitting there, beaming with this new child, was like magic. She seemed complete. Daddy looked handsome and content, sitting in the driver’s seat with his wife and two sons within his reach. I could hardly believe it—I had a baby sibling! I was thinking, This could be fun! Jimmy, my baby brother, looked like a toy I could play with, he was so cute. We were a happy little family with a promising future ahead of us.

Sadly, although I did not realize it, Momma King would never again be my babysitter. By the time my mother returned to work several years after my brother was born, I had started school and no longer needed a full-time babysitter.

But throughout my life, I visited Momma King every few years. People frequently remarked that it was so sweet of me to visit this lonely old widow. Well, perhaps it was sweet of me, but I didn’t visit Momma King only for her sake. I also visited her for my benefit. Everyone needs someone who has known them from an early age, who loves them unconditionally and who believes that they can do no wrong. Momma King has always been that person in my life. Her love flowed freely, extravagantly, unencumbered with judgments. She just loved me simply for who I am, her “sweet little Richie.”

Years later, just weeks after I had gotten over my denial and finally admitted to myself I was gay, I went home for a Christmas visit. Just a few weeks before I took a long, hard look at myself in the mirror and said, “Rich Merritt, you’re a homosexual.” I was twenty-five, still in the Marine Corps, and I hadn’t come out to anyone else yet. While I was visiting my family I went to see Momma King and she told me a story about a relative of hers. She said, “You know he’s one of those homer-sexuals.” That’s the way she pronounced it. But then she quickly added, “But what do I know about that? He is my family and I love him—and you know we’re all God’s children, anyway.” God, I still cry when I think of that—to hear this old woman make that statement at that particular time in my life was just absolutely extraordinary. It was the first time I ever heard anyone back home say something so nonjudgmental about being gay.

Yet her gentle statement also made me somewhat uneasy because it forced me to consider whether God approved or disapproved of what I felt and of what I had done. I had pushed that issue aside for months, and now here was this saintly woman adding new dimensions to my confusing thoughts.

But that was all a long way in the future. Before kindergarten, my life had consisted of listening to my parents’ sweet voices read books to me, playing in the sandbox beneath the oak tree, catching lightning bugs at night, and curling up by the fireplace in the winter to watch cartoons and The Brady Bunch. Long summer days. Hot summer days. My cousins would come down and my mom would babysit for them. My mom’s side of the family was five miles up the road in nearby Powdersville, South Carolina, and we’d all play games under the trees in the backyard.

It wasn’t always play. We’d have to work in the garden on those hot summer days, picking green beans and squash and okra. But even by doing that, we were in touch with nature and loving the outdoors, despite the mosquitoes and other bugs. I slept very well at night after playing and working so hard. I loved it all. Heaven really was a place on earth. I was happy. Life seemed easy.

I’m telling you all of this so you get an idea of what my childhood was like. My life on the outside seemed very simple—it revolved around my immediate family and religion. To say it plainly, our religious faith was the center of the family. For example, my dad had taken an old antique wagon wheel from the 1800s, which—with some paint and glass—he converted into our coffee table. Placed on the center of this table, rather symbolically, were a family photo album and a large white Bible. Every night before we went to bed, we’d gather around that coffee table with my dad reading from the Bible and then we’d all pray. Our family devotions lasted from twenty minutes to an hour each night.

From the time I was born until I was five, we were members of the Pentecostal Holiness Church which, to me, now seems really wacky; for example, people speaking in tongues and, in extreme cases, handling live snakes. (I never saw any snake handlers in person; we weren’t quite that backward.) My family went to church every Sunday morning, Sunday night, and Wednesday night, and I was totally happy with it. I thought everyone did that because almost everyone I knew did do that. Even the members of my family who didn’t go to church paid lip service to God and Jesus and the Bible.

Oh, it wasn’t all that extreme. Generations before, Pentecostals weren’t even allowed to see movies, dance, have parties, anything like that. Grandpa Schrader, who was Pentecostal, didn’t think women should wear makeup, have a perm, or have their hair colored. In my day, they were a little more lax about that kind of thing. My mom would say, “Any ol’ barn can use a coat of paint.”

Along with The Brady Bunch, my brother and I were allowed to watch some other television shows. My favorite show was Bewitched. I imagined how much fun it would be to be Samantha, living a relatively normal and happy life among mere mortals, but having a special secret that made her unique.

“That Uncle Arthur sure is a sissy!” Momma said as she and I laughed at the character played by Paul Lynde. Soon enough, I would come to dread that word, but at this point, I was too young to understand what it meant.

Of course, there were some programs that were totally off limits. Shows like Sonny and Cher, All in the Family, and later Three’s Company, were all taboo. But I do remember trying to sneak a few glimpses of the spectacular Cher when my mom wasn’t looking. I guess that was a hint of things to come.

Martha Rogers was my Sunday school teacher at the Pentecostal Holiness Church. She was my first teacher, and I loved her dearly. She also paid special attention to me, setting me up to be a lifelong teacher’s pet. One morning as she read from the Old Testament to the assembled group of five-year-olds, one segment in particular caught my attention, “And the Lord God rained fire and brimstone down on Sodom and Gomorrah because of the sin and wickedness of that city.” I was fascinated as I imagined the horrific scene of fire raining down from the sky, people running, mass hysteria. Martha continued: “He had commanded that no one turn and look back at the city, but Lot’s wife disobeyed the Lord,” Martha said, almost whispering the deadly judgment that was to come. “God turned Lot’s wife into a pillar of salt.”

I was confused. I tried to imagine what purpose was served by a pillow of salt. Could you sleep on it? Did the salt get in your mouth as you slept? Was it comfortable or was it crunchy? Years would pass before someone would correct my misguided notion that the Lord had taken a pillowcase and stuffed it with salt made from Lot’s disobedient wife.

Then Martha added, “The Lord destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah because they were wicked.”

“What was so wicked about them?” a child asked

Martha didn’t have a quick answer. “Well…in Sodom…and, well…I suppose in Gomorrah, too…” she stammered, “they…people, er, men…had, um…men married other men.” She seemed relieved, as if she discovered the word “married” just in the nick of time.

No Sunday school teacher has ever held the attention of a group of five-year-olds more raptly than Martha Rogers held ours that summer morning. We were amazed. Men marrying men? My only thought was: A home with no mother? Who would cook the meals?

After church services every Sunday, my family piled into the car to drive less than a mile to Grandma and Grandpa Schrader’s house for Sunday afternoon dinner.

As soon as the car door was shut, I announced, “Mrs. Rogers told us about a place where men marry men.”

Momma looked at Daddy in horror. “What is she teaching them, Paul?”

My dad hesitated his usual minute or two before responding, “San Francisco?”

That didn’t sound right. How could my parents not know this? “It’s in the Bible,” I said.

“There’s no place in the Bible where men…,” my mom began.

“It had fire and a pillow of salt,” I said, giving them more clues.

“Oh,” my dad said, laughing, “You mean Sodom and Gamawrah.” Daddy’s voice, with his gentle Southern accent, was always warm and easy, especially when he was laughing.

Momma laughed too, but added, “I don’t think they’re old enough to be learning about that.”

Because my mother held the title of chief disciplinarian in our household and my dad was the more congenial of the two, the idea of a home with two men intrigued me. But surely that was something that occurred only in Biblical days. The idea of a man marrying another man in modern times was even more unlikely than balls of fire raining down from the sky, or a person being turned into a pillow of salt.

My educational career began at Tabernacle Baptist Church and Christian School on the west side, the poorer side, of Greenville. My cousins Charlie and Glenda were a year ahead of me in school and they went to Tabernacle, so naturally, I wanted to go there. Their younger sister, Amy, who I loved (and love to this day), would also be going there.

When I started school I didn’t have any friends. Frankly, I don’t remember being close to anyone outside of my family. I kept to myself—and I was content that way. At the time, I didn’t feel excluded. It’s just that I was shy and introverted. I was still trying to feel my way about.

My first teacher, Mrs. Hand, was my inevitable introduction to the dark side of life. She was a total contrast to Mrs. Rogers, my kind and gentle Sunday School teacher who adored me. Without a doubt Mrs. Hand was the meanest person I had ever met. One thing, which was totally shocking to me, was that Mrs. Hand loved to paddle her students. Who knew what personal demons had led her down the path towards turning into such a cold, evil witch? All I knew is that she was a witch and her choice to become a teacher dealing with children was a wrong one. Whenever she had an opportunity to spank a kindergartner, which was often, I could see pure joy light up in her eyes, even through the thick lenses on her horn-rimmed bifocals. It was pretty sick. Unfortunately on several occasions, I saw that joy directed at me.

Even as a child I had been abnormally sensitive to pleasing others. I was always trying to do right, to gain the grown-ups’ approval. It was all the more troubling to me that nothing I seemed to do would please Mrs. Hand. To her, justification for punishment was never a serious concern. If Mrs. Hand wanted to slap your wrist or beat your behind, she’d find her own reasons.

My first incident with the dreaded woman is etched in my memory. Chapel service was a daily ritual at Tabernacle Kindergarten. Students met at the end of each morning to listen to Bible stories and sing children’s songs about Jesus. The teachers would take turns leading the kindergarten in chapel. It was during one of Mrs. Hand’s turns to be in charge that I “earned” her uncompromising wrath.

Our small chapel contained several rows of church pews. By the age of five, I was already fascinated with church pews, primarily the way that, no matter how crowded they became, as if by some Biblical miracle, another human body could always be added onto the end of the row. That belief was in full force one day during one of Mrs. Hand’s chapel services. One five-year-old body after another was pressing its way into the end of my pew, forcing the rest of us to slide down to accommodate someone else.

We all stood as Mrs. Hand was about to lead the group in prayer (I learned early on that God doesn’t like to spoken to by mere humans who are seated). I tried to slide to my right to make room for even more students entering the row. The boy to my right, Lewis, who was significantly larger than myself, refused to move.

“Slide over!” I whispered to Lewis.

“No,” Lewis responded, adamantly. And he didn’t budge.

Even from that short exchange, the entire room suddenly became deathly quiet. I looked to the front and saw Mrs. Hand laser-beaming an evil stare through her glasses directly at me.

“Richie Merritt,” she hissed through clenched teeth, “Go to the classroom!”

Never before had I felt such terror. I walked out of the chapel to the classroom. Alone in the room, I sat in my chair in the darkened room, too ashamed to turn the lights on, waiting, waiting.

Finally, the other students slowly trickled into the classroom, each of them taking their turn to give me the look that in the olden days was reserved for the pagans.

At last she appeared. She glared at me for a while, blinking through her bifocals, then she said, “Richie, do you want to tell me what happened?”

I actually deluded myself into thinking that Mrs. Hand wanted to hear the truth. “We needed more room in the pew,” I reasoned, “so I was just asking Lewis to slide over.” I relaxed a little, convinced that my sincere explanation would win me an acquittal.

Instead of immediately pronouncing me “not guilty,” Mrs. Hand turned to Lewis and asked, “Lewis? Is that true?”

I was offended. Never before had anyone questioned my integrity!

“No,” Lewis lied.

I froze in my seat.

Mrs. Hand removed her paddle from its usual, prominently displayed position on the wall and slowly moved her portly body in my direction.

“I’m going to paddle you,” she said slowly, enjoying the taste of the words, “not because you talked in chapel, which I saw you do, but because you lied to me. Hold out your hand.”

My first public execution and no blindfold. I gave her my hand and she whacked it hard over and over. I opened my eyes just long enough to catch the faces of the other students. Much to my astonishment, they were enjoying this as much as Mrs. Hand. Didn’t they feel any empathy for me? Couldn’t they see what a grave injustice was taking place? Why hadn’t anyone stood up for me?

I did not tell my parents about the paddling. I could not let them know that their little boy was now a failure. All I could do is hope the school officials would not tell them anything and I could keep this dirty little secret. But there were other incidents with Mrs. Hand, and each time was the unbearable fear that my parents might find out.

It was all the more upsetting to me, because I was being treated this way by a woman. She was so different from my mother, Momma King, Martha Rogers, and all my aunts. Before Mrs. Hand came along, I had all these close, wonderful relationships with the women in my life. Then along came this woman who I couldn’t seem to please. I remember being disturbed my whole kindergarten year. It made an impact because it was the first clue that maybe this wasn’t heaven on earth after all. Being good, doing what’s right, trying to please, didn’t automatically mean you’d be rewarded. There were bad things. Bad people. Injustices. Things I couldn’t control. I thought it was me, of course, but in retrospect, I see that she was no worse with me than she was with the others. As her student, however, I didn’t recognize that. I just noticed school simply wasn’t working for me. I kept wondering, What am I doing wrong, that I can’t make Mrs. Hand happy? Up to that point, and for many years to come, every move I made was an attempt to make other people happy.

There were other things in those primary years that were becoming unsettling to me. You must understand that I was a very gentle boy. I was always closer to the women in my family than to the men. Other than my kind and gentle father, the men were sort of gruff. They weren’t warm and friendly and polite and courteous—all the things that I was. In truth, they scared me. A couple of my uncles, particularly my Uncle Herbert, really frightened me. I also had an Uncle Howard who was very mean.

And when I was about five, my Uncle Robert would always call me a sissy. Maybe it was a joke. I don’t think he called me a “sissy” because he saw me as effeminate. He called my brother that too: “Look at the little sissy.” He’d say the same thing to my cousin, Greg. Uncle Robert would laugh and I don’t know if he intentionally meant to hurt my feelings. But it would bother me. A sissy was the worst thing you could call a boy in the South, and being called that probably hit me harder, because somewhere buried deep inside myself, I feared that I might actually be one.

We’d have a big family dinner and after the meal the women would migrate to the kitchen and dining room, cleaning up. The men went somewhere else—either outside or to the living room. I would always stay with the women. I felt more comfortable with them, listening to their soft, calm voices, except for Aunt Lydia, who was kind of loud. As I got older, the other people in the family began to notice my preference. I recall my mom once or twice saying, “Why don’t you go in there with the men?” These were subtle things. I didn’t let them bother me, really. But, still, they were there and there were other things that were beginning to add to my uneasiness.

Tabernacle is also where I learned to dread recess and the playground. My cousin Amy, who was a four-year-old preschooler, and I were very close. She was a tender soul and I always felt very comfortable with her. We looked alike and felt the same way about a lot of things. Amy and I got together whenever we could at kindergarten. When I was with Amy, I enjoyed the time on the playground. Our meetings were usually limited to recess, however, because we were separated by a grade most of the time. When she wasn’t around, I preferred to play by myself, left to explore the fantasy world in my head. I even had an imaginary friend, Susie, who I often used to replace Amy when she was absent.

One day while I was seated alone on the bleachers, daydreaming, I was jolted into reality by the comment of a girl walking by.

“Look at that kid,” she said to her friend, unmindful that I could hear her. “He’s always by himself.”

I was puzzled. I not only thought the girl was unkind—pointing me out to her friend—but I also thought she was a liar. I wasn’t always alone, I was usually with Amy, and even on this day, I was with my pretend friend, Susie. But of course I could not tell them that.

I watched the two girls as they walked by. Had she intended to criticize me? It had never occurred to me before that being alone was something undesirable. While I enjoyed my time with Amy, I didn’t mind being by myself. Was there something wrong with it? With me? The time I spent with my family was what really mattered to me because, at this point, home was a very supportive environment. As long as I was going to be leaving school and going back home, I was fine knowing that “aloneness” was sometimes an option for me.

I looked around the playground and it was as if I had been let in on a secret—most of the other kids were playing with someone, or in a group. There were only a few other isolated souls on the outskirts of the playground area.

I tried to think of a solution but the alternative to being alone, I realized, was unthinkable. I would have to talk to someone, or worse, play ball. That I could not do. The boys scared me. And so, I stayed where I was. Alone.

The next day, Amy was at school and she and I met on the playground after class, our usual allotted recess time. We were next to the driveway under a tree when a couple of Amy’s friends approached us. I thought that this was nice, we were less alone now and people wouldn’t pick me out of the crowd for being abnormal. I welcomed meeting these girls, and Amy and I enjoyed their company.

Suddenly, I heard a familiar voice behind me. Amy’s face brightened with recognition and when I turned around I saw my dad standing there. He had arrived early to pick me up. I said goodbye to Amy and my new friends and hopped in the truck with my father without giving it a second thought.

At dinner that evening, Daddy said to Momma, “Guess who I saw Richie with today on the playground when I picked him up?”

Oh good, I thought, Dad is going to tell Mom that I have some new friends.

“He was hanging around with a group of girls,” my dad said. Then he turned to me, “You aren’t a sissy, are you, son?” I’m sure he was joking and didn’t mean any harm. But there was that word again! I felt a lump form in my throat.

“No,” I replied, looking down at the table. And then I couldn’t think of anything else to say.

My father’s statement was another painful awakening. It was the moment—shaded with time, but clear with emotion—when I first had the impression that maybe there’s something wrong with the way I was. I mean, before my father said that, I was okay. I would rather sit with Amy and her friends—the girls. I wasn’t comfortable trying to play ball with the boys. But once my dad pointed out to me that there was something wrong with it, I was caught in this: I’m not at ease playing with the boys, yet I’m not supposed to be playing with the girls. What the hell am I supposed to do? That was the beginning of discomfort about who I was.

The following day I was determined to solve the problem. My dad would not have to ask me again if I was a sissy. I tried to play ball with the other boys, but I soon realized it wasn’t working. My dad had been a football player and my mom played basketball. Even to this day, my mom tells a story about how, when I was a little boy, they would take me outside and throw me the ball and I just wouldn’t play. I would stand there and cry. My dad would joke around and look at my mom and say, “Who was it, Ruth? The mailman? The milkman?” I took that to mean that my dad was not “owning” me.

When, a bit older, I did try to play with the boys, I could only do it for a few excruciating minutes at a time. Then I would get their ridicule and criticism. I kept trying to play with them but I would inevitably mess up. By trying to remedy my dilemma I made it worse. Before that usually no one noticed me at all. And as long as no one noticed me I was fine. It was when they saw that I was not able to be like the other boys when it became horrible. I learned the real and terrible truth: the other boys did not want to play with me.

But it wasn’t something I worried about all the time, really. I think I had a typical child’s short attention span, along with a resourceful nature of trying to make things work. If I was rejected by the boys, it bothered me for awhile, and then I would distract myself with something else—like chasing a lightning bug—until it would be out of my mind. At least the conscious mind.

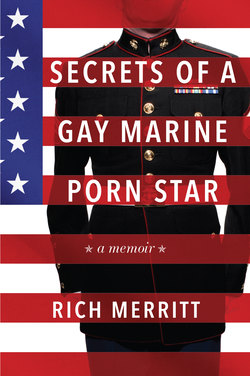

Long before my photo appeared on the cover of The Advocate—uncovering my history in porn—my little Southern community was familiar with sexual scandal. Like the time it was discovered that a woman in the church, Hattie May, was having a torrid affair with Preacher Jim, the minister. Preacher Jim’s wife was my Momma’s best friend whom I also loved dearly. She used to read “Winnie the Pooh” stories to me and I’d cry whenever Pooh got stuck in the honey tree. That made the scandal up close and personal although years would pass before I learned what had happened.

In my Daddy’s eyes, Hattie May and Preacher Jim were safe from being damned to hell for all time because he believed in eternal security, meaning, once you were “born again,” you were always “born again,” forever safe in accepting Jesus Christ. I liked the sound of that…“eternal security.” Sort of like a “get out of jail free” card. Grandpa Schrader didn’t agree with that concept. He believed that, even if you were born again, if you sinned, you “lost” your salvation. Over the years, they’d argue about this theological point for hours and hours. Momma and her younger sister would cry because Daddy and Grandpa were arguing. Jimmy and I would fall asleep waiting for the end of an argument that would never be resolved, at least not in this lifetime.

Grandpa Schrader, the godliest man I’d ever known, lay on his deathbed, terrified that he had sinned somehow and God wouldn’t let him into heaven. He didn’t believe in eternal security but he sure as hell believed in and feared eternal damnation.

Religion and relatives, like most of Southern society, are two of the three pillars of my family. Race is the third. The three “R’s” of being a Southerner. Your life revolves around them.

Your race determines where you live, where you go to school, where you go to church, where you shop and where you work. It determines whom you hang with and whom you can marry.

“Richie, what’s a cryin’ shame?” asked Uncle Herbert.

“I…I don’t know.” Uncle Herbert always made me nervous.

“It’s an Atlanta school bus goin’ over a cliff with an empty seat in the front!”

The meaning of the joke was obvious to any Southerner. The city of Atlanta was 64% African-American. Its public school system was even more overwhelmingly African-American because many white students attended private schools. The punch line was that an empty seat on an Atlanta school bus going over a cliff was a wasted opportunity to remove two or three African-American children from the human population and gene pool.

My uncles and cousins and sometimes the preachers used to sit around telling “nigger” jokes. I’d laugh because that’s what I was supposed to do, but the older I got the more it bothered me. I wish I could say it annoyed me enough to speak up, but the most I ever did was storm out of a family dinner in protest when I was a teenager, already letting out some of the budding drama queen that was lurking inside of me.

“Well, you really showed yourself today!” Momma said. I told her I didn’t like what her brothers and the others were talking about. She was somewhat sympathetic, but felt that making a grand and sweeping exit from the table wasn’t the way to make a point.

Division, strife and conflict were everywhere. After Preacher Jim’s affair with Hattie May became public knowledge, he was forced to resign from the pulpit. The new preacher brought Christian rock music—including electric guitars—into church. Daddy immediately disapproved. In a major family schism, we left the Pentecostal Holiness Church and became Baptists. Not just Southern Baptists—they were too liberal. We joined an Independent Baptist church in the city. It had over three thousand members.

Right after we joined, our new church admitted its first interracial couple. My folks didn’t approve of interracial marriages, but at the same time, they didn’t think an interracial couple who were already married should be denied membership in the church. Bob Jones University, however, had major problems with it and there was another big schism in the Christian community in Greenville, South Carolina.

Daddy and Momma said that by 1972, when I started school, the state was going to start forcing integration. The schools would have to lower their standards so that the blacks could pass. They wanted high standards for us so the way to get that was to send us to an all-white school, even if we didn’t have the money for tuition.

Even though I kept the paddlings from Mrs. Hand I had received at Tabernacle Kindergarten a secret, my parents had grown dissatisfied with the quality of my education at Tabernacle. They told me that the following year I would be transferring to a new school on the east side of town. My new school’s name was Bob Jones Elementary School and it was on the campus of Bob Jones University.