Читать книгу Honed - Rich Slater - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter I

ОглавлениеInto the Black Canyon

The Leavitt Accelerated Free Fall School and Black Death School of BASE

The Leavitt Accelerated Free Fall School did not have a dean’s office, much less a campus. It had no phone listing in the Yellow Pages and its proprietor didn’t have a business license, insurance bond, or even a sign on the side of his car. There was no alumni booster club and, unfortunately, no cheerleaders. In fact, it only had one student that day in the spring of 1981. The tuition was entirely reasonable.

“Go buy a rig so I know you’re serious – and pay for my jump,” said Randy Leavitt to Rob Slater, who readily agreed.

The summer before, while making his first ascent of El Cap, Rob’s concentration on climbing a tiny crack thousands of feet above the ground was interrupted by a skydiver whizzing past, flashing toward the valley floor at 100 miles per hour before popping his parachute and floating effortlessly to a soft landing in the meadow below. In a matter of seconds he had descended a distance that would take Rob nearly two weeks to climb – and hours to descend. Turning back to the strenuous task of setting protection and working his way upward, Rob vowed that he, too, would someday fly.

“I’m never going to walk down from the top of El Cap again,” Rob declared.

Sometime later, Rob found his way to a parachute center, whose name he never mentioned to me. There, he made four military-style “static line” jumps, where he leapt out of the plane and had his parachute automatically opened at the end of a ten-foot line attached at one end to the airplane and at the other end to his parachute.

There was no freefall involved in those first jumps and, according the conventional static line training method of the time, it would take Rob another 30-50 freefall jumps of progressively longer “delays” to learn the freefall skills necessary for him to competently parachute off El Capitan.

“This is going to take forever,’” Rob realized, frustrated he couldn’t learn to skydive in a few weeks or months. An opportunity, however, arose by chance one evening on Boulder’s Pearl Street Mall.

Rob ran into his climbing friend Leonard Coyne, who was hanging out with well-known climber and fellow Colorado University student Randy Leavitt. In 1979, Randy became the first person in the world to climb and then parachute from the same cliff. Randy had climbed El Capitan’s Excalibur route and then dove from the top of the Dawn Wall route made famous in Warren Harding’s book, Downward Bound. Several months later, Randy climbed the Shield route and jumped again from the Dawn Wall. This time, though, he met a greeting party of park rangers when he landed in the meadow.

“There was legal jumping there for six weeks in 1980,” Randy said, “and I got ratted out by some skydivers there eager to show the rangers that they could police themselves.” Randy paid the price of the skydivers’ pathetic appeasement with a few days in the “John Muir Hotel,” as the Yosemite jail was called, followed by a lengthy probation.

Rob knew of Randy’s exploits and immediately proclaimed how cool he thought it was and that he wanted to do the same thing. There was something different in Rob’s gung-ho demeanor that made Randy think Rob might be serious, but he wanted to test his new acquaintance’s mettle. Randy invited Rob to go climbing and the two quickly became friends. Rob referred to his new buddy as “RSL,” short for Randall Stephen Leavitt, “The Leavittator,” or simply as “Randall,” being one of the few to call him by his official moniker.

RSL, with more than 200 jumps at the time, had gone through conventional static line training school in Elsinore, California, but he believed Rob could learn at a much faster pace. As a honed climber, The Leavittator reasoned, Rob already knew how to perform under threat-of-death stress and knew and had confidence in the nylon and high-grade steel components that climbing and parachuting gear shared.

“I gained a lot of respect for Rob through his climbing,” RSL said, “and for more than just his skill. I’d climbed with other guys who were as good or better, and some who were faster learners, but with Rob, more than anything, it was his determination that stuck out in my mind. I saw the mental determination that he would accomplish whatever he wanted to do, that when he set a goal, it was not question of could he do it but how fast. When it came to jumping off cliffs, he was going to do it. It was only a question of when.”

Unlike ski areas or scuba schools, which tailor training programs to fit the learning pace, physical ability and financial means of individual customers, essentially all U.S. parachute centers use a “one size fits all” approach to training. If Rob went the conventional route to parachuting competency, it would take a lot of time and money.

But it wasn’t Rob’s style to follow the traditional path and, fortunately for him, RSL had a better idea. From their mutual belief in the inadequacies of convention, the Leavitt Accelerated Free Fall School (LAFFS) was born. Simply put, RSL would teach Rob how to jump the same way people learned how to climb. The Leavittator would lay out the basics of technique and equipment and proceed at whatever pace Rob could handle physically and mentally.

The final piece was Rob getting a complete parachute system, consisting of a main parachute, reserve parachute and harness-container system before the training started. This would confirm to RSL that his new student was indeed committed to seeing the process through and not acting on some short-term “Gumby” whim. With purchasing guidance from RSL, preceded by a serious dip into his sacred climbing fund, Rob soon acquired a decent parachute rig that met RSL’s requirements. The LAFFS was thus set to commence.

The Leavittator started with the basics: “Get a properly open parachute over your head before you land or you die.”

“Cause of death – impact,” they both laughed.

RSL showed Rob how the gear worked and how similar it was to climbing equipment in terms of materials, strength and manufacturing standards. He showed him how to correctly pack the chute and get “rigged up” in his parachuting apparatus. Basic aerodynamics were explained so Rob understood how his wing-like “square” parachute moved through the sky and how he could control its direction, rate of descent and landing force by using the toggles at the end of the control line on each side.

“Without the chute you bounce,” RSL told Rob, “but do it my way and landing will be like stepping off a phonebook.”

Next, RSL had Rob lie on the hood of a car and assume the basic “arch” position used by all parachutists to stay stable in freefall. With arms and legs spread a comfortable distance apart, back arched, head high, hips thrust downward, the arch allows for the unimpeded and all-important proper deployment of the parachute when it came time to “pull.”

“Skydiving’s pretty easy compared to climbing,” RSL told Rob, “but you can’t screw up any of the four or five things you have to do right. It really is pretty basic: Arch your back, if you start spinning, dive out of it and re-arch.” If something went wrong, he could correct a problem before bouncing.

Under RSL’s watchful eye, Rob practiced his arch until he’d developed enough muscle memory for it to feel reasonably natural and comfortable. He also practiced putting his gear on and off, “checking his handles,” and doing all the other things an experienced jumper would know and do by heart. Satisfied Rob at least acted like he knew what he was doing, RSL matriculated him from the LAFFS ground school and began outlining his first-jump dive plan.

Rob would jump out and assume the arch position, followed shortly thereafter by RSL. Rob would try to maintain the arch position, hold a heading and check his altimeter until he reached an altitude about 3,500 feet above the ground, the standard pull altitude for less experienced jumpers. It provided several more seconds to open the parachute or, if there was a problem, jettison the main parachute and deploy the reserve.

Pulling at 3,500 feet would also give Rob a longer parachute ride and more time to figure out how to control it, get it aimed in the right direction and have plenty of time to line up and otherwise prepare for landing.

RSL stressed the importance of staying stable – but also the even greater importance of pulling at 3,500 feet no matter what.

“Even if your parachute malfunctions because you’re not stable when you pull,” counseled RSL, “you still slow things down and that’s better than trying to get stable all the way to cause of death – impact.”

“Cause of death: panic and impact-and being a pussy,” Rob added, laughing.

Then he had Rob mentally practice his landing approach and “flare” – simultaneously pulling down both toggles to slow the parachute’s forward and vertical speed. Rob practiced his landing procedures and even stepped off the curb and a phone book to cement the visualization in his mind.

When RSL deemed Rob ready to jump, he presented him with a blank skydiver logbook, used by jumpers to faithfully and honestly record the dates, locations, altitudes, and free fall times of their jumps. Like pilot flight logs, they are sworn records of accomplishment that are not to be trifled with lightly, and are used by parachutists to officially document their skills and experience when they go to commercial parachute centers.

Of course, no parachute center would allow Rob, with his four static line jumps and no freefall experience, to get on a plane and jump out of it at 10,500 feet. A paper record was needed to match what RSL considered to be his actual ability. That little technicality seemed a not insurmountable problem for persons of intelligence and ingenuity, which Rob and RSL certainly believed themselves to be. Rob sat down, logbook and pen in hand, and forged entry after entry of bogus jumps he would claim to have completed.

When his list topped 50 jumps, he tucked the log book in his pocket, loaded his chute in the car and set off with his friend The Leavittator to the jump site at the Loveland-Fort Collins Airport 40 miles northeast of Boulder to the Sky’s West Parachute Center. Rob’s bogus logbook passed muster at the manifest counter and RSL and he soon found themselves climbing aboard a Cessna 206 jump plane with four other jumpers.

About 20 minutes later and 10,500 feet higher, the first jumper slid open the segmented Lexan jump door and looked out to “spot” the aircraft. At the appropriate moment, the sky divers would jump out where they had the best chance to land on target.

When the blast of air hit him, Rob knew he was about to literally plunge into a new and exciting part of his life. But the thought passed quickly. It was time to do exactly what he had learned at the LAFFS, all ending with a “…step off a phone book.”

The first step was a lot higher. After flashing a big grin at RSL, Rob dove from the airplane and instantly found a freedom and exhilaration he had never before known.

It didn’t seem like Rob was falling as the plane floated up and away from him like a balloon, quickly becoming a small dot against the sky. As he hurtled toward the earth at terminal velocity of 120 miles per hour, Rob felt the wind against his body. In his peripheral vision loomed the square summit block of Long’s Peak and the other great mountains of Colorado’s Front Range. Rob was suspended in space and time, centered, and totally happy. He felt free.

Rob also felt stable and didn’t tumble or spin. When it was time to pull, he was in a good body position to allow the parachute to open properly.

Reluctantly, Rob reached for his main parachute’s pilot chute, a 30-inch diameter round mini-chute that begins the main parachute deployment process. He had already learned the only “ripcord” on modern parachute systems is on the reserve parachute.

Rob threw the pilot chute into the airflow, where it inflated and served as a portable, in-air anchor for the parachute that stretched out below it as Rob fell earthward. When the main parachute reached “line stretch,” Rob felt the hard, comforting jolt of a parachute that opened perfectly.

“It’s hellacious,” he said later, “to look up and see that it’s open the way it’s supposed to be.”

Rob grabbed the toggles and steered his parachute through the sky toward the drop zone landing area at about 25 miles per hour. Sometimes he turned left, other times right, to compensate for the wind and stay aimed at his target. He also practiced his flare several times by pulling the toggles down until the wind noise stopped as he momentarily floated motionless in the sky.

After a final practice flare, Rob let up on the toggles. The parachute resumed its normal speed as he lined it up for a landing into the wind to give himself the lowest possible groundspeed at touchdown.

Rob flared at just the right time and successfully concluded his first-ever freefall jump and airfoil parachute landing. Moments later, RSL touched down beside him.

“You were right Randall,” Rob grinned. “It was just like stepping off a phone book.”

As they gathered up their parachutes, Rob couldn’t help but to look back up at the blue of the empty sky and think back to the El Cap jumper who had flown past him, sparking his immediate vow to someday fly. Now he had flown too. It had been an indescribable rush – but it wasn’t the end of his parachuting road. Rob didn’t want to just jump out of airplanes at commercial parachute centers. He had much more in mind.

Rob made nine more jumps with RSL, after which RSL pronounced Rob to be the first graduate of the Leavitt Accelerated Free Fall School. Rob was now good enough to load onto an airplane at any drop zone and competently handle himself in the wide-open skies above. But to successfully jump El Capitan, he needed to learn more than RSL could offer.

“I was more into climbing than jumping,” RSL recounted, “and I was still on probation from my El Cap jump, so I couldn’t take Rob all the way through his first BASE jumps. I thought it would be better to hook Rob up with someone who was a better fit for that part.”

RSL introduced Rob to Robin Heid, an experienced skydiver, skydiving instructor and pioneering BASE jumper – a parachutist who jumps from Buildings, Antennae, Spans (bridges) and Earth (cliffs). Robin was one of the first 50 people in the world to jump with a parachute from a fixed object and had already jumped El Capitan twice. Most recently, Robin had been part of a six-jumper group that made the first-ever descent into Colorado’s notoriously dangerous Black Canyon of the Gunnison, a 2,000-foot-deep chasm that contained some of the most hideous big-wall climbing in North America.

“I’d met a jumper at Elsinore named Larry Yohn who had moved to Colorado,” RSL recounted, “and I was teaching him how to climb because he wanted to be the first person to climb El Capitan with a peg leg. Larry knew Robin and thought he’d be the perfect choice to take Rob to the next level, so one day we all got together at Eldo.”

“When Randy introduced us,” said Robin, “I remember this strong, vibrant, grinning guy, confident but not cocky, ready to learn, who knew he could handle what came at him.”

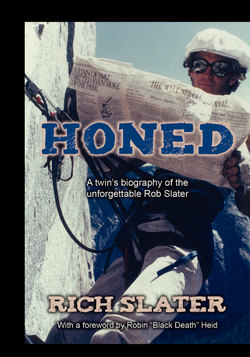

Rob looked up to Robin as a renowned adventurer in a honed new sport that he himself wanted to enter. Robin was also a writer with an extensive, colorful vocabulary and way with words – including the use of “black death” to describe any endeavor where the threat of fatal or serious injury laid in wait for the incompetent and the unlucky.

It wasn’t long before Rob, who liked giving nicknames to his friends, although he didn’t have one of his own, began affectionately referring to his new friend as “Black Death Heid” or “BD” for short. In Rob’s mind, a good nickname immortalized in a good-natured way some aspect of the person which Rob admired or found amusing.

Before they could commence, though, they had to agree on a fee. Like the Leavitt Accelerated Free Fall School, tuition at the Black Death Heid School of BASE (BDSB) was entirely reasonable.

“You teach me to climb, I teach you to jump,” said Robin Heid to Rob Slater, “and pay for my jumps.” The tuition was higher because, after all, it was graduate school.

Rob readily agreed and thus began what Black Death Heid calls his “most amazing learning experience.” On Saturdays, they jumped and on Sundays they climbed. On Saturdays, BD pushed Rob so hard he gritted his super-white teeth in frustration. On Sundays, Rob made BD beg for mercy as he took him on routes no one with a month’s worth of technical climbing would even consider – even someone named Black Death.

“I don’t do anything that easy unless I’m with a girl,” Rob would laugh as BD protested a particularly featureless or overhanging section he wasn’t sure he could surmount. Black Death then usually did, though on the times when he couldn’t, Rob’s nickname for him temporarily became “Haul Bag Heid”.

The net result was “a lifelong friendship and a fast learning curve for both of us,” said BD.

Rob and Black Death Heid made a dozen climbs and 15 skydives together. On the rock, BD became a pretty good climber who could lead some respectably difficult routes “if they’re not too strenuous,” as Rob would add in reference to BD’s technique-to-fitness ratio. In the sky, Rob became more than respectable in the skills he needed to jump off El Capitan, fly his body away from the cliff, open his parachute at the right time and land decently on target.

They started with basic forward movement in freefall, then simple turns, then front and back loops, all with an eye toward making Rob feel comfortable and to gain, maintain and regain body stability at will. After opening, there was in-air parachute flight coaching followed by detailed debriefs after landing. As expected, what BD called Rob’s “equivalent-risk experience” as a climber allowed him to progress as quickly as RSL had envisioned.

When BD was satisfied with Rob’s basic proficiency, he added the element for which Rob had long waited – “tracking.” Configured like a ski jumper, Rob learned to fly forward one foot for every foot of fall. Tracking was a must-know skill for Rob if he was to realize his El Cap BASE jump dream. Tracking on an El Cap jump was critical to get him the 200-300 feet of separation from the wall he needed to safely deploy his parachute.

“I’d have him fly to me in freefall and we’d hold hands, or ‘dock,’” said Black Death. “Then I would turn 90 degrees and slowly assume the track position and have Rob follow. At first, he flailed all over the sky, but in short order he started holding a heading and moving horizontally.”

BD showed Rob no pity and cut him no slack as he left Rob in his skydiver dust for several jumps. Then Rob could stay with him for a while before falling back at the end of their track. But it wasn’t long before Rob mastered the track to the point that BD had to work at it to stay ahead.

“Pink steel!” Rob proclaimed of his newfound prowess as a human torpedo, shooting across the sky exactly where he wanted to go. Sometimes it included aiming directly toward the not-too-distant Long’s Peak.

“You know everything you need to BASE jump,” Black Death Heid proclaimed when they landed on jump number 25. “Next stop, the Black.”

Not long after, they found themselves on the North Rim of the Black Canyon at Serpent’s Point atop the Painted Wall, looking down at the spring runoff-gorged Gunnison River almost a half-mile below in the central Colorado mountains.

That day, though, it was only BD who wore a parachute. BD wanted Rob to watch without the distraction of having to jump immediately thereafter, by himself, without his trusty jumpmaster. They stood on the edge as BD “dirt dived” the jump. Black Death would launch, track, open and navigate his way through the formidable canyon to his designated landing spot on a small sandbar on the north bank of the river opposite a much bigger one on the south bank.

“North side takes the river out of play,” BD explained to Rob, “but way tighter. South side’s bigger but then you have to cross the river. I’ll probably end up on the north side, but if for some reason I have to bail, I can divert to the south side.”

“Like you said,” Rob replied, “have a Plan B, C and D too!”

Rob then took his place slightly downstream on a rock cropping where he could see the whole jump – and get a good launch photo, of course.

Black Death Heid’s jump went just like the dirt dive: relaxed arch launch with a fast, smooth transition to an eight-second track followed by parachute opening and a leisurely 45-second “S-turning” approach and center-punch landing on the north-shore sandbar.

“Black Death Heid!” Rob shouted, clapping his hands and grinning broadly, “All right, Black Death!”

Rob was totally enthralled by what he’d just seen – and more confident than ever that he could duplicate BD’s feat the next day.

With Black Death Heid and his mother Joan watching and taking pictures, Rob did just that. BD called Rob’s first BASE jump “technically and judgmentally perfect. He did it exactly the way I did except he chose at the end to land on the big sandbar, which was the smartest thing he could do because he literally hit the middle of his envelope.”

As Rob explained it, “I wasn’t worried about crossing the river, but I was a little worried about hitting the small landing area, so it was an easy choice.”

After Rob landed, he used a pre-arranged signal to let BD and Joan know he was okay, running several circles around his parachute. Then, he stuffed his chute into a backpack, made an effortless, completely dry crossing by jumping over the raging roiling water from one boulder to another and trotted up the heinous, tick- and poison ivy-infested SOB Gully in two hours. Rob rendezvoused with Joan and BD, who pronounced him to be the first graduate of the Black Death School of BASE.

The next day, Rob jumped again – and nailed it again. Afterward, as he drove back to Denver with Black Death, Rob knew for sure that some day soon his El Capitan jump would happen. He also knew that he had found another mistress, at least for a while.

Meanwhile, the innovative wheels in BD’s mind had been turning as he watched over and shared in Rob’s BASE jumping exploits. Rob had quickly gone through the 10-jump Leavitt Accelerated Free Fall School and BD’s 15-jump Black Death School of BASE. BD saw no reason why the traditional parachute training courses couldn’t be dispensed with for others of the similar honed persuasion. There was even a new parachute training technique he could use to eliminate the need for an airplane.

“A major parachute manufacturer had come up with a towing method by which you could learn to fly an airfoil parachute without first jumping from a plane,” BD explained later. “It was a great idea in theory, because you could give your students a lot of low-cost reps without the cost, gear and fear of a real parachute jump. They could get ready and confident more quickly.” It seemed to be the perfect addition to what RSL and BD had done with Rob.

Unfortunately, the system was still in the test phase and suffered from what turned out to be a fatal flaw: catastrophic results from too much tow line tension and no way to see it coming. If the tow vehicle drove faster than the parachute could fly, or atmospheric conditions added tension to the tow line, the parachute would “lock out” and dive into the ground like a kite with no tail in a high wind. In other words, the situation would go critical before anyone could react to it – even when a “tensiometer” was installed to monitor tow line tension.

More unfortunately, the lockout accidents to date had been few and almost exclusively attributed to pilot or tow vehicle driver error.

One warm day in May, 1982, BD, Rob, Leonard Coyne and The Great Matt, another of Rob’s climbing partners, all assembled in a wide-open field on the east edge of the Rocky Mountains foothills near the infamous Rocky Flats nuclear weapons plant. The plan was to put Verm Sherman, yet another of Rob’s climbing partners, under the towed parachute and teach him how to fly it. Naturally, BD would test the system to make sure everything would work right before putting a noob, or rookie, under the nylon.

A climbing rope was hooked on one end to a car, with the other to a carabiner attached to BD’s parachute harness. Then, with Leonard and The Great Matt alongside, the three of them ran down a road until the canopy filled with air and lifted off. BD was soon soaring more than 50 feet above the ground. Everything looked great until the tow car turned through a curve in the road, increasing the tension on the tow line. The canopy started bucking, locked out, tipped over and slammed BD to the ground.

“He hit so hard, we all thought he was dead,” Leonard Coyne said later. “When the parachute covered him and he didn’t move, we were sure of it.”

But BD was honed and he survived, though he spent a month in the hospital and another month in a body cast recovering from a broken back, shattered ankle, broken foot and separated shoulder. For Verm, watching BD crash and burn closed the door on any further thoughts of “non-traditional” parachuting schools – or parachuting at all.

“The only way you’re getting a chute on me is if the plane’s going down,” Verm concluded.

For Rob, thinking his friend BD was dead made his heart sink, but his spirit quickly soared when they raised BD’s impromptu parachute shroud to find that conclusions about his death were premature. A still-breathing though not-bleeding Black Death Heid blinked his eyes at them and said, “Okay, what happened?”

Rob spent hours at BD’s hospital bedside. Together they recounted the ill-fated events of that day with irreverent laughter. BD had taken it to another level and Rob had been there. They also discussed that, although BD hadn’t died that day, the towed-parachute training concept had. When news of BD’s accident reached the manufacturer, it immediately canceled the project.

“No reason to stop jumping, though,” said BD, with Rob, of course, concurring. Neither of them considered giving up skydiving or BASE jumping just because one parachute ride didn’t work out. Rob greatly admired BD and his renegade mentality and, while some members of Rob’s climbing team may have acted only in support of Rob’s periodic feats of apparent insanity, BD was brave enough to dance on the edge himself. For Rob to renounce this mindset while one of its most esteemed adherents lay in a hospital would have been an unconscionable act of betrayal. Rob and BD knew the risks and accepted the possible negative outcomes as a requirement of getting to that special place they both craved so much. Neither wanted or needed accolades, critique or sympathy. As Black Death Heid told me later, “People like Rob and I are more afraid of not living than we are of dying.”

While Black Death Heid cooled his heels in the hospital, Rob and RSL continued climbing together locally in preparation for their upcoming summer trip to Yosemite Valley, or “the Valley” as they called it, checking off route after route on their respective lists of Eldorado and Boulder Canyon climbs. During one of those climbs, Rob told RSL that the Black Canyon was a “Gumby jump” that hadn’t been nearly as challenging as he’d expected.

“Okay, then,” RSL riposted, “if that’s a Gumby jump, let’s raise the bar and make it more interesting. We’ll do a two-way – and then climb the wall instead of hiking out.”

Rob instantly agreed.

“That’ll make a great picture!” he declared, then added, “Plus it will be the world’s first jump-climb!”

Though the previous solo jumps RSL and Rob had made into the Black Canyon had gone off without a hitch, things went wrong fast soon after they stepped off the edge.

“We launched from the little ledge on Serpent’s Point that BD calls ‘The Serpent’s Tooth,’” RSL recounted. “I took the grip on Rob’s wrist because I had more experience and wanted the control in case something happened. I did the countdown and when we went off, Rob went head-low, so I let go.”

RSL started tracking and watched as Rob dove head-first down the cliff for a few seconds before he started tracking away.

“It was maybe the most vivid moment of my entire life,” said RSL, “watching the pegmatite stripes going by me, watching my buddy in freefall going past the stripes and the canyon just swallowing him up. I gotta hand it to Rob; I was really impressed by his ability there. He was totally under control the whole time, and totally aware of where he was and what he needed to do. Even as he tracked away, he kept looking over his shoulder to find me to make sure that we had enough separation to not hit each other on opening.”

Once Rob assured himself of good separation, he “dumped,” or deployed his chute, at 300 feet – way lower than he’d planned. Rob’s parachute opened facing back toward the wall. Because he opened too low to reach either sandbar, Rob now faced landing options that were only slightly less heinous than hitting the wall and experiencing a first-hand taste of the “Pinball Effect.”

Splashing down in the Grade 6 rapids was sure death by drowning. Crashing into a boulder-and tree-strewn hillside across the Gunnison River was just as sure a visit to the emergency room. Rob chose the least horrendous option of landing downwind at high speed on the south-shore sand bar covered with ankle-breaker rocks. Rob hammered in, badly mauling his foot, but was otherwise not seriously injured.

Maintaining his focus during those imminent-death moments as he plummeted toward the bottom of the canyon slowed down time for Rob. It enabled him to coolly process the situation and extricate himself from danger, all the while getting to savor the experience. Those moments were all his, in a special place and state that risk, determination, courage and focus allowed him to reach.

There would, however, be no effortless dry crossing of the rapids this time. Rob couldn’t even walk on the damaged foot, much less climb and jump between house-sized boulders. Rob was a strong swimmer and at first thought about just swimming across the Grade 1 rapids. After the battering he’d taken, though, he decided against it. Fortunately, they had stashed gear for their planned triumphant free climb up the previously aid-only 5.9/A3 Journey through Mirkwood route. RSL retrieved a rope and flung one end to the “madman across the water.”

But there was nothing mad about Rob crossing an icy, fast-moving mountain river with a bum foot – as long as he had a rope. After all, he’d been a captain of the high school swim team. It would be a piece of cake.

Rob pulled the rope tight across the river, then waded in, but was immediately swept straight downstream and across the strong current. He and RSL drew on individual strength and climber teamwork to get Rob to the north shore with no further damage. A piece of cake, just like he figured. Safely on the right side of the river, they then planned the rest of the trip out of the Black.

Free climbing Journey through Mirkwood, of course, was out of the question. They would have to get out of the Black Canyon through the SOB Gully, a two- to three-hour hike for strong young men with two good feet but a hideous, heinous, horrendous crawl through poison ivy, ticks and gnarly boulders if one is either figuratively or literally lame.

It took two days for them to get to the top. RSL could have hiked out and been back the same day with rescuers, but to Rob, that would have been poor style that not only detracted from but ruined an otherwise seminal event. Calling for help when they were both still alive and mostly ambulatory was unthinkable.

Afterwards, Rob didn’t dwell on the event as a near-death experience so much as a nearly perfect one. So he hurt his foot and got banged up on the landing. Rob and RSL made a spectacular jump together and survived some adversity in freefall with good style. The epic crawl out of the canyon afterwards just added to the experience. It made the satisfaction of successfully meeting the challenge that much better. As Rob told me the story afterwards, though, I wondered what challenge Rob really meant and what was he really trying to overcome?

Whatever it was, Rob healed fast from his Black Canyon adventure and soon he and RSL were in Yosemite, where Rob realized his dream of climbing, then jumping, from El Cap.

The winter before, Rob had shared a house in Boulder with some fellow CU students. On his bedroom wall he’d hung a topographical chart of the Pacific Ocean Wall, a death-defying sustained overhang of aid climbing more than 2,000 feet high and one of the toughest routes on El Cap. At the top of the topo, Rob had written “SOLO THIS ROUTE.”

The P.O. Wall had never been soloed. Rob had never done a solo aid pitch more than 50 feet long. Throughout that winter, Rob often sat in his room, with his coat on and the windows open, staring at the topo and his scrawled protestation to himself.

The summer after he learned to skydive and made his first BASE jumps into the Black Canyon, Rob was back in the Valley where the dream had started. Rob proceeded to solo the P.O.Wall in five days and then parachuted off, just like the anonymous diver who had inspired him years before.

“Right then I knew I’d keep jumping off El Cap until I got caught,” Rob said. A short time later, he almost did. As I previously mentioned, Rob repeated his climb-jump feat by climbing the Sea of Dreams with RSL and Mike O’Donnell, then jumping off. He may have got more excitement than he bargained for after he landed, but getting chased by rangers didn’t deter him from wanting to jump again.

When Rob returned to Colorado in the fall of 1982, he no longer had a parachute system. But Black Death Heid wasn’t yet using his, so Rob borrowed BD’s gear and set his sights on the Denver skyline, crowned by the 700-foot-high, still-under-construction City Center tower. I was a student at the University of Wyoming while Rob was attending CU, and one weekend our respective schools played a football game in Boulder.

“Saturday night after the UW-CU football game my twin brother Robbie’s going to parachute off the tallest building in Denver,” I announced to my beer buddies. “We should go watch.”

“I’ll drive!” responded Ken Bull, aka “The Chief,” my childhood friend with a proclivity to tack on a specific descriptor to anything of which he approved. “That’ll be fuckin’ righteous,” The Chief added, true to form.

After the game my friends and I, along Rob and his friend Tom Kaplan, piled into the Chiefmobile, a humongous 1972 Olds Delta 88 complete with bondo spots and a four-foot skull and crossbones covering the hood, for the midnight journey to Denver. We linked up with Black Death Heid, who had started jumping and climbing again the month before but wasn’t yet ready to BASE jump.

City Center was Denver’s newest and tallest building and, being still under construction, sported a huge crane on its top. The crane would make Rob’s jump safer because jumping from its end put him 30 feet away from the building before he even started.

Before taking his official photographer position, BD stashed my friends in a good spot to watch, though they would have preferred to wait in the bar instead of in the darkness of a deserted downtown street. Kaplan, Rob and I headed for the building and scaled the ten-foot chain link fence surrounding the construction site. We knew we’d be sitting in the city jail if we were caught – but I didn’t care because I was with my brother.

We made it inside without being seen and began to climb the 54 flights of metal stairs to the roof. I offered to carry Rob’s parachute as a gesture of brotherly affection and because I wanted to be involved as much as possible. For those reasons and, in a gesture of common sense, Rob graciously agreed.

We emerged on the roof to a spectacular view of downtown Denver and the dark nearby mountains. The crane was far bigger up close than it seemed to be from the ground and we discovered in short order that the interior shaft containing the ladder up the crane tower was locked.

“Why would they lock this? Do they think someone’s gonna climb up here in the middle of the night?” Rob asked mockingly.

Rob rigged up and got ready to go, then the three of us climbed the first 20 feet on the outside of the crane’s skeleton before we could wedge ourselves through the steel lattice inside to the ladder. We hoped we wouldn’t have to do the same thing at the top. After all, I joked to Rob, “that would be dangerous.”

Luckily, there were no locks at the top and we gathered ourselves at the intersection of the crane’s tower and arm. We were literally on the summit of Denver. Looking out to the end of the crane’s arm to where Rob would launch was like looking at the edge of space.

“Richie, want to go out there with me? It would be a cool picture,” Rob asked.

“Sure,” I replied without hesitation. While Kaplan remained at the intersection, I followed Rob out to the end of the crane arm. When we got there, we looked back, each releasing one handhold on the crane to display a clenched fist for Kaplan’s camera. Rob then explained his flight plan:

“I’ll circle to the right in front of that building and then back to the left over those power lines and land in the parking lot.”

Seven hundred feet below, the skull and crossbones of the Chiefmobile were barely visible. Rob and I looked at each other.

“I love you,” he said.

“I love you, too,” I replied. The “L” word wasn’t regularly used between us – it didn’t need to be. We also both felt that using it with girls was weak and extremely poor style. But there at the end of the crane arm, it seemed like the right thing to say.

Rob grinned at me and stated confidently, “I’m taking the easy way down.”

“See you at the bottom,” I grinned back, confident of what he was about to do. In truth, climbing out on the end of the crane with no form of protection was extremely foolhardy – but I did it without hesitation because I was with Rob. With Rob I always felt safe. I believed the feeling was mutual and tried to validate his belief in me. I also knew if something went wrong and Rob met his demise, I would follow. To stay behind in safety and in fear would be an abandonment of my brother as he went into the unknown alone. But I was sure he would make it and the thought quickly passed.

Rob launched and I listened as he counted patiently before throwing out his pilot chute. True to his word, when the canopy cracked open, Rob swooped to the right in front of the building across the street, cranked to the left over the power lines far below and landed near his cheering crew and the getaway car.

On top of the crane, Kaplan and I were no less ecstatic. Boy, did we have great seats. Once we knew Rob was safe, however, the adrenaline began to dissipate and we realized where we were.

“Let’s get the hell off here.”

On the Denver television news the next evening, the anchor reported that “an unidentified maniac was seen parachuting off the crane on the top of the City Center late last night.” They didn’t mention another unidentified maniac on the crane without a parachute and they failed to report the real story; that Rob was now one object closer to earning his BASE number.

Earlier, during their mutual quest for BASE numbers, Rob and RSL agreed that BASE numbers were actually rather silly. Skydivers assigned themselves many different numbers, such as when they completed certain formations during group jumps. Nevertheless, Rob and RSL also agreed they should get their BASE numbers. In truth, they realized that BASE jumping was simply too risky to continue long-term and both planned to retire to adjoining 40-acre tracts on the north rim of the Black Canyon, even though neither had the parcels yet nor the money to buy them. But they wouldn’t be able to do that if they were both dead.

After the City Center jump, Rob was halfway there. He had an “E” for earth and a “B” for building, but he still needed an “A” for antenna and an “S” for span, which could be a bridge or a domed stadium. Fortunately for Rob, both were within easy reach in the state of Colorado.

Most accessible was a 750-foot-high TV antenna at the summit of Lookout Mountain, guardian of the canyon entrance through which Interstate 70 winds its way into the Rocky Mountains. At night its lights, save for the blinking red one on top, shine indistinguishable from the stars bright enough to be seen over the glow of the city.

“BASE jumping is a great spectator sport,” Rob told me more than once, not because he wanted to show off, but because he liked sharing his exhilarating, adrenaline-fueled adventures. To that end, Rob invited a couple of his friends to join Black Death Heid and him for a planned jump from the antenna. Unfortunately, their first two trips to the base of the mountain were greeted by raging winds, which prompted Rob and BD to matter-of-factly abort the “mission.” The second stand-down brought howls of dismay from Rob’s friends, who were sick of 4:00 a.m. wakeup calls for nothing. They urged him in profane and insulting terms to jump anyway. Ever the diplomat, Rob told them his decision to launch would not, with all due respect, be swayed by their impatience, inconveniences or unkind references.

“The mistletoe hangs from my coattail; you can begin from there…”

Despite his willingness to share the fun with friends, Rob never lost track of the fact that BASE jumping was not only incredibly dangerous, but intensely personal, with challenge, achievement and validation playing itself out in the deepest reaches of his soul. When Rob got to go to that special place, it really didn’t matter to him if anyone watched or not. Rob and BD eventually jumped the Lookout Mountain antenna in good conditions on another night.

“Perfect form again,” said Black Death Heid, “although there was one wild moment for both of us when his pilot chute towed until he had enough speed that the drag overcame the friction of the too-tight pack job I’d done for him. By staying cool, he got a clean, straight opening and it ended up as a routine jump with a little spice in the middle.”

After getting his “A,” Rob needed only the “S” – not just to get a two-digit BASE number but to become the first-ever Colorado BASE.

Soon thereafter, BD and Rob made a midnight drive two hours south of Denver to the small town of Canon City, best known as the location of the state penitentiary. Nearby, over eons of time, the Arkansas River has gouged through the Sangre de Cristo Range to carve what is now known as the Royal Gorge. If the Black Canyon can be compared to a 2,000-foot funnel, the Royal Gorge must be likened to a 1,000-foot eyedropper. Spanning the gorge, the world’s highest suspension bridge hangs 1,055 feet above the river and single railroad track occupying the narrow canyon floor. The Royal Gorge below the bridge is only 100 feet wide, which makes for trickier wind conditions and demands much greater parachute handling skills.

Distinguishing the Royal Gorge from the Black Canyon is the fact that one is wilderness and the other one is a tourist attraction. The Royal Gorge Bridge goes nowhere except to the other side, as it was built in 1929 solely to generate revenue for Canon City. Also distinguishing the Royal Gorge from the Black Canyon is its ease of access and popularity with regular tourist-type folk. Royal Gorge Park offers ample paved parking, a Visitors Center, an inclined railway to the bottom and an aerial tram across the top.

Naturally, it was too windy to jump when they arrived that first night, so they camped out in Rob’s car. As the winds blew so strong they rocked the car, Rob and BD catnapped between wind checks, hoping it calmed enough to allow a jump.

“At least they’re strong enough that there’s no doubt about the decision,” Rob said when they finally gave up just before dawn and drove back to Boulder.

Not long after, Rob and BD went south again, this time with me along for the ride, and this time during daylight. The plan was simple: just pay the entrance fee, drive in, walk out onto the bridge and jump off-in broad daylight. We paid our entrance fee at the gate, parked in the lot and headed for the bridge. Strolling along in jeans and light jackets, we stared over the edge into the abyss like everyone else, as the narrow bridge swayed slightly in the breeze.

I proudly strode to the middle of the bridge with my twin, BD trailing with his camera. We blended in just fine except for the fact Rob was wearing a parachute. BD had cameras, but so did every other sightseer at the park, and most of them wore or carried backpacks similar in size to Rob’s parachute rig. No one even noticed us – until Rob tossed a roll of toilet paper into the abyss to check the wind.

As we raptly watched it snake its way downward, people suddenly became aware of what was really going on. They rushed to the rail on our side of the bridge to investigate and started snapping pictures.

Rob decided the winds were good enough for jumping and, with the concurrence of the eminent Mr. Black Death, decided it was time to launch. He climbed the railing and stepped onto the foot-thick main suspension cable with agility and ease, pilot chute in hand, his mop of curly brown hair waving in the wind. He steadied himself for a moment and then looked back over his shoulder to me with the same fierce determination and kind of wide-eyed grin I saw on the City Center crane.

“This is the ultimate sport,” he proclaimed.

“Go for it,” was as profound a reply as I could muster.

With that, he turned and leaped into space. The crowd that had grown instantly larger when Rob stepped up onto the cable let out a collective gasp, then held its breath. They didn’t know if they were watching some poor soul commit suicide – or just somebody honed having fun. My eyes widened and my mouth opened. We all leaned over the railing to watch as Rob quickly shrank in size to a fast-moving speck.

“One, two, three, four…” I could hear Rob count before he threw his pilot chute. With a crack muffled by wind and space, the canopy opened several hundred feet below and the crowd cheered loudly as Rob began spiraling into the depths of the gorge.

Once I saw Rob’s chute open, I relaxed somewhat. I knew he was enjoying the ride and I did the same. Otherwise the ride was silent but for the commotion on the bridge by the spectators.

“Did you see that?” was asked repeatedly in the first five seconds after Rob’s parachute opened. BD and I looked at each other, nodding. Yeah, we most certainly had.

As Rob neared the canyon floor, the crowd kept oohing and ahhing but I tensed as I flashed back to Rob’s Black Canyon crash landing. What if he landed in the river or got caught in a wind shear and pinballed into the jagged cliffs? If I had to watch him die, I would probably go right off the bridge after him. But again, the thought quickly passed as another cheer went up, this one louder, when Rob made a stand-up landing on the railroad track and could be seen scampering to gather his chute. It was easy for me to see the excitement in his step and feel his exhilaration rise up to me at my place on the bridge.

As we walked back to the car, the excitement and pleasure on our faces was no different from that of the dozens of people who got way more than they paid for that day at the Royal Gorge Bridge.

Meanwhile, a couple of Royal Gorge security guys at the bottom briefly gave chase, but they were clearly unenthusiastic about catching someone who moved so fast and probably equally unmotivated to nab someone who had just done something so cool. As BD said to me with a grin as we watched the unsuccessful chase play out, “Would you want to try to chase down someone who was crazy enough to jump off a 1,000-foot bridge?”

“Only to give him a high-five,” I replied.

Rob ran down the tracks until he was out of the bridge sightline and then climbed straight up out of the canyon at a speed no one on the bridge company staff or the local police anticipated. We picked up Rob on the entrance road while the authorities were still looking for him at the bottom.

“Richie, that was so great!” he said to me, his eyes still wild with excitement. I told him I knew. Black Death Heid just smiled and held out his hand to Rob.

“Congratulations,” he said to my twin as they shook hands. “You are now Colorado BASE Number One.” After submitting his information to the U.S. BASE Association, Rob also learned that he was “world” BASE number 43, four numbers behind RSL’s number 39 and one ahead of BD’s 44 that came a few months later. In so doing, Rob and RSL raised the bar for hard-core climber-adventurers everywhere. After Rob earned his BASE number, many of his BASE jumping cohorts, who were also climbers and had thought the numbers were silly, suddenly decided they wanted theirs as well.

Rob wasn’t quite ready to retire from BASE jumping, though, and his leap off the City Center crane wouldn’t be the only time an unidentified maniac would be spotted flying off a skyscraper in the heart of the Mile High City. On a crisp winter weekday, he climbed the stairs of a still-under-construction One United Bank Building, another Denver 700-footer with a distinctive “cash register” top, with fellow BASE jumper and movie stuntman Brian Veatch. Ironically, unbeknownst to Rob, he would work in that same building years later.

The two jumpers arrived at the 50th floor, dressed in work clothes and hard hats to avoid arousing suspicion among the numerous construction crews at the site. Reaching their launch point without detection, they geared up on the building’s southeast corner. Rob would jump from a window on the south side and Brian from an adjacent window on the east side. Far below on a bus stop bench, Black Death Heid waited with his camera.

As they climbed into their respective windows, the outside-the-building construction elevator stopped and opened on their floor. When the workers stepped out and saw them poised to jump, one of them blurted out: “Don’t jump! It’s not worth it!”

Brian laughed and said, “It’s okay; we have parachutes!”

Rob grinned his trademark grin and gestured for the workers to join them. “You can watch if you want to!”

Rob and Brian then turned to the business at hand, counted “Three… two… one… see ya!” and out the windows they went.

The jumps were perfect. Both landed without mishap in an adjacent parking lot and, barely a minute after launch, Rob and Brian were whisked away into traffic. The event barely caused a ripple in the ebb and flow of the city’s normal business.

BD’s photo of the jump appeared soon after in a back cover advertisement in Skydiving Magazine, world’s most important parachuting journal. In the photo of Brian and Rob under open parachutes, in the windows from which they jumped several hard hats can be seen.

Eventually Rob did retire from BASE jumping, after a career which defied convention, law enforcement and death. To show for it, his name appears in the annals of the sport, he got some great pictures and was even mentioned on TV, albeit as “an unidentified maniac.” Vivid memories remained of the purest experiences of exhilaration and freedom. For years afterward, Rob kept a packed parachute at the foot of his bed, just in case the urge struck.

“That’s what it all boils down to; committing suicide and living through it,” Rob concluded. But what did he really mean by that and why would he say such a thing? Was it just another of his colorful, outrageous statements or did he really feel that way? Did Rob have a death wish or was there something more? Do I have one too? Why did Rob need so much to continually return to that special state and place? To figure out the answers to these questions and the reasoning behind them requires us to go back to the beginning…

Into the Royal Gorge

BD Heid on the Royal Gorge Bridge

On the City Center crane