Читать книгу Honed - Rich Slater - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter III

ОглавлениеWith Dad and Grandpa Slater (Robbie on right)

“I’m gonna do it.” –Rob Slater “Anything worth doing is worth overdoing.” –Rich Slater

When I was fresh out of law school, trying to build a practice, I used to pass out my business cards in the local biker bars and strip joints. I rationalized it was good marketing and, admittedly, they were the kinds of places I sometimes liked to patronize. Inevitably, I found myself doing a lot of criminal defense cases. Down at the courthouse in Cheyenne, the defense lawyers joked about the old adage that “the nut doesn’t fall far from the tree,” in reference to some second-or third-generation defendant again showing up in the criminal justice system. While the adage unfortunately held true for those hapless souls, fortunately it was also true for my twin brother Robbie and me. Like everyone, from whence we came shaped our personalities and our destinies.

When Robbie and I were four, Dad took us on our first camping trip. He got both of us a knapsack, and we each put in a bowl, spoon and box of our favorite cereal – Cap’n Crunch. The army surplus canteen with the canvas sheath was filled with milk. Paul, who was only three and Tommy, who was still learning to walk, stayed at home with Mom.

We were living in Salisbury, Maryland, so Dad took us down to the flats along Chesapeake Bay and we crowded into our small canvas Sears and Roebuck pup tent, seeking refuge from the clouds of mosquitoes. There were so many of them, though, that we went home early that night. It was the first and only time we didn’t make it through the night.

Many successful camping trips followed and by the time Robbie and I were 10 years old, all of us considered ourselves outdoorsmen. The little knapsack was replaced by aluminum-framed backpacks. Dad always carried the heaviest pack, with the tent, stove, cookware and most of the food. The rest of us vied to see who could carry the second-heaviest pack, lining up at the bathroom scale the night before a trip.

In the evenings, we had campfires. We waited with great anticipation the coming of darkness, when Dad might let us light torches. Sitting around the fire, or in the tent, alone in the wild, amidst the silliness between four boys and a tolerant if not encouraging father, Dad told us stories. We loved hearing about Dad as a kid and the rest of our family history.

As he spoke, Dad would gaze into the campfire. Periodically, he jabbed and rearranged the burning logs with a stick he called a “poker.” This was “tending” the fire as he called it. We all learned how to tend the fire and competed to find the best poker.

Grandpaps Hannah, for example, our great-great grandfather on our Dad’s side, was a war hero, Civil War, Union side. Leading an escape from a Confederate POW camp, he went back to help a fallen comrade, but got shot in his heel, Grandpaps Hannah still managed to make it to freedom, along with the guy he rescued.

Grandpap’s son-in-law, our great grandpa Audrey Vernon Slater, was a farmer in West Virginia near the Pennsylvania line. In 1900, our grandpa, William Alvin “W.A.” was born. Four months later, his dad Audrey cut his thumb shucking corn. It became infected and his thumb was amputated, but that didn’t catch all the infection, so he had to have his arm was amputated above the elbow. This also failed to stem the tide of infection and his condition worsened and so, at the ripe old age of 36, Audrey Vernon Slater died. Medicine, Dad explained, was quite different back then and many people died from infection. Nevertheless, my brothers and I were sure that Dad could have saved great grandpa Slater. Finishing up this chapter of our family history, Dad told us Audrey’s widow Minnie Jane Hannah cared for young W.A. until she died in 1908 at age 40, having outlived her husband by four years.

His Royal Highness Prince Luigi Amedeo di Savoia, Duke of the Abruzzi, was a member of Italian royalty, but he was no soft, pudgy doughboy slacker of the genteel idle rich. He had eyes tightened by weather from peering into the distance and hands roughened by time spent in the wild. The Duke was missing two fingers, lost on an 1899 expedition to the North Pole. He had also led expeditions to tropical Africa to explore the legendary Mountains of the Moon in Ruwenzori and to Mount Logan in Canada.

The Duke carried an array of scientific gear on his expeditions to perform topographical, meteorological and photogrammetrical surveys. On his Alaskan expedition, the Duke brought along a brass bed, perhaps a manifestation of some immutable royal gene or, perhaps, merely for comedic relief. The Duke didn’t hang out at the castle, slouching on an embroidered sofa eating cream puffs. He made the most of the good cards life had dealt him and sought adventure for more than just the thrill. According to Robbie, the Duke of the Abruzzi was honed.

“Good work if you can get it,” Rob would say.

The Duke set out for K2 in 1909 with 262 waterproofed and meticulously prepackaged porter loads for the final leg of the journey to base camp – minus the brass bed. K2 was serious business and besides, the drafts allowed by a raised bedstead made it impossible to stay warm.

His Royal Highness brought along over 450 pounds of small change, budgeted for hiring and paying local Balti porters the most generous consideration of one rupee per day. The Duke’s expedition would become the model for all future ventures into the Karakoram and Himalayan ranges.

The expedition’s main camp was established at the base of K2’s southern faces at the head of the Godwin-Austen Glacier. After several days on the southeast ridge, the Duke was forced to call off the attempt at 19,685 feet. Although he had set a personal altitude record, he was still nearly two miles below the summit.

The party then directed its efforts around the western base of the peak. Ascending what he dubbed the Savoia Glacier, after his home province, the Duke and his team topped the Savoia Pass at 21,870 feet. Upon reaching the crest of the pass, no acceptable route could be found through the pinnacles, rock towers and massive cornices to the Great Mountain’s upper slopes.

“As a reward of his labors, what the duke thus saw utterly annihilated the hopes with which he had begun,” Filippo de Filippi, the expedition geographer, would later record. “The excursion to the westward side of K2 had not revealed any feasible way of ascent.

The Duke never made it to top of K2 and, following his 1909 expedition, he never returned to the Karakoram. But in the dreaming and planning of K2 adventures, his spirit has remained.

W.A., or Grandpa Slater to my brothers and me, went to live with his Grandpaps Hannah when he was eight. According to Dad, the young boy and his war hero grandpap lived a rather odd life together, which no doubt contributed to their respective unique personality quirks. Grandpaps was known for smoking Mail Pouch chewing tobacco in his pipe. One of W.A.’s favorite foods was stale popcorn in a bowl covered with tomato juice. “A delicacy,” Grandpa Slater would tell us.

Dad’s mom, our Grandma Slater, was a quintessential grandmother. There were always large jars of homemade sugar and oatmeal cookies waiting when we arrived for a visit. Surreptitiously, with an irreverent twinkle in her eye, she would let us steal “just one more” before dinner, as long as we didn’t tell Mom or Dad.

In 1929, another royal, the Duke of Spoleto, led an expedition of scientific exploration to K2 and the Karakoram area. In 1937, Brits Eric Shipton, Michael Spender, Harold Tilman and seven Sherpas explored K2’s Northern Flank. The next year, an American expedition including Bill House ascended what is now called House’s Chimney. House, and Wyoming’s most famous climber, Paul Pedzoldt, the founder of NOLS and Rob’s first real climbing mentor, reached an altitude of nearly 26,000 feet. In 1939, Fritz Wiessner’s American expedition succeeded in establishing nine high altitude camps on the mountain’s southeast ridge, now known as the Abruzzi Ridge in honor of the Duke. Wiessner and Sherpa Pasang Dawa Lama reached the height of over 25,000 feet without oxygen. On the way down, Dudley Wolfe and three Sherpas were lost, becoming K2’s first four victims.

The summer Robbie and I were 16, Dad took us with him to visit his father, our Grandpa Slater. While we were there, Grandpa, who was 76, decided it was high time to learn to ride a bicycle. A trip to the local department store produced a shiny new 3-speed and, in no time, Grandpa was cruising around the neighborhood. Also in no time, Grandpa was in the emergency room with a broken hip. For the remaining 14 years of his life, Grandpa walked with a limp. Never, though, did he wear a helmet.

“Grandpa Slater is honed,” Robbie would say, using his favorite term to pay his highest compliment. I agreed. I liked his unique use of the term “honed” so much that I used it too. Since Robbie was my identical twin, I believed I had license to use it without attribution whenever I wanted. To be called honed by Robbie meant something and it most certainly applied to our Grandpa Slater.

One of our favorite Dad stories was about Bud Ruble. We would all be in the tent, lined up in our sleeping bags. Dad, staring up at the ceiling of the tent and, judging from the look on his face, fondly looking back in time, recalled that he “had a friend who lived a couple blocks over on Alta Vista Street. His name was Bud Ruble and he called himself the “Earl of Alta Vista.” My brothers and I would start to snicker. What a great nickname.

“Bud Ruble thought, in his mind at least, he was some kind of local royalty,” Dad continued. “One day in sixth grade science class, we were all asked to bring something from home related to the study of biology. Bud Ruble brought a chicken in a bottle.” To this day, Dad isn’t sure where Bud got it; he thinks it was some kind of bottled meal. By this point in the story, we were giddy with the excitement of what we knew happened next.

“All the kids and the teacher gathered around and Bud started explaining that it was a real chicken in the bottle. Then the Earl tried to yank the chicken out through the bottle’s narrow neck, but it wouldn’t come out. The kids started laughing and the teacher was starting to get angry. Bud kept trying to pull it out and started saying ‘Come out of there, Bessie.’ The teacher’s name was Bessie Yater, and she chased the Earl of Alta Vista out of the classroom with ruler in her hand, yelling, “Bud Ruble you come here.” It was complete pandemonium,” Dad concluded, summarizing the scene with a simple statement.

It would approach pandemonium in the tent at this point as all of us, laughing, would start doing our own Bud Ruble impressions, calling out, “Come out of there Bessie.”

“Bud Ruble was a funny guy,” Dad always concluded. Years later, after hearing the story for the umpteenth time, Robbie would always add: “You might even say a comedic genius.” We all admired the guts displayed by the Earl in this stunt. We also, especially Robbie, admired the honed nickname the Earl of Alta Vista had bestowed upon himself.

Dad grew up in Moundsville, West Virginia, a small town on the Ohio River in the finger-shaped protuberance at the top of the state. The coal industry dominates the region’s economy and the mine entrances can be seen amid the thick forests that blanket the surrounding hillsides. Grandpa Slater, at various times, worked as a farmer, school teacher and ran a shop which re-upholstered furniture. He instilled in Dad a basic notion which played an important role in shaping his life: “Remember, the way out of the coal mines is through the university.”

During high school, Dad worked at the local pool each summer. It was a place where kids of all ages congregated.

“Someone donated an old rubber World War II raft which, without fanfare, was thrown in the pool for community use,” Dad told us. Dad and his fellow lifeguards, who were in charge of pool safety, watched with amusement as the raft quickly became the object of a water-borne version of “king of the hill.” Inevitably, “kids started dive-bombing the raft from the high board and there would be bodies flying everywhere,” Dad continued. This part always got our attention. “That would be so fun!” my brothers and I agreed, “but didn’t they get in trouble for jumping off the board onto kids in the raft?” we wondered.

“Are you kidding?” Dad replied rhetorically, “Back then there weren’t any parents coming around interfering or complaining.” My brothers and I knew there would never be an old World War II raft at our local pool, but if there was, we also knew our Dad would let us dive-bomb it from the high board, regardless of what the other parents said.

The 1938 K2 Expedition that included Wyoming climber Paul Petzoldt was the first attempt by an American team to summit the world’s second-highest but most horrendous mountain. The team was equipped with all the latest in high-tech outdoor gear, including wool mittens, canvas tents and leather-strapped, buckle-up crampons. Climbing without supplemental oxygen, Petzoldt reached an astounding height of 25,600 feet. It was a world record at the time, but it was still half a mile below the summit.

Petzoldt, who grew up in the mountains of Wyoming, first summited the Grand Teton at the age of 16. Later in life, when asked why he climbed mountains, responded:

“I can’t explain this to other people. I love the physical exertion. I love the wind, I love the storms: I love the fresh air. I love the companionship in the outdoors. I love the reality. I love the change. I love the oneness with nature: I’m hungry; I enjoy clear water. I enjoy being warm at night when its cold outside. All those simple things are extremely enjoyable because, gosh, you’re feeling them, you’re living them, you’re senses are really feeling, I can’t explain it.”

Many of Dad’s classmates followed their fathers into the mines. For those who didn’t, it wasn’t so much the coal mines were a filthy, dangerous and deadly place to work, but rather an education was the only way to gain true independence. To do something productive, provide for yourself and be your own boss was the means, with independence being the end. To achieve the means, Grandpa told Dad, you had to “get an education.”

Football was a big deal in Moundsville and in the many small communities throughout the state. The whole town turned out for the Friday night games. Dad was on the football team and, at six feet, 185 pounds; he played both offense and defense – quarterback and linebacker. My brothers and I already knew Dad was tough because of it; the shoes had real spikes and, although he was required to wear a helmet, it was made of leather and had no face mask. But Dad didn’t dwell on that.

“I was pretty good backing up the line,” Dad would admit, which was as close as we ever heard him come to bragging. He even downplayed the way his toughness got him that “education” his father had told him was so important. In his senior year at Moundsville High, Dad was selected to play in the all-star game at the end of the season, where he earned the game’s Most Valuable Player award and a football scholarship to West Virginia University. When pressed to describe how he had won the scholarship, however – did he score ten touchdowns, make all the tackles, intercept passes – Dad would only say “they had to give it to somebody.”

Dad didn’t wear his toughness on his sleeve. It was no more necessary than conspicuous consumption. The important thing was that it was there. As kids, Dad taught his boys to box and how to defend themselves. With those skills went a couple of simple rules which were absolutely inviolate to the Slater brothers: “Never start a fight, but always finish one,” and, “If one of you boys comes home beat up, you better all come home beat up.” The Slater boys never picked fights and they never all came home beat up.

To us, Dad was the manifestation and a living example of the lessons and values he and Mom had always tried to impart upon us and our sister Elizabeth, who we called Sissy. Independence, hard work, doing your best and following your dreams were the unifying principles. Integrity and respect for oneself and others were the foundations of Dad’s world view, which he demonstrated by his deeds as much as he taught by his words.

Dad set a high standard. We kids realized we were lucky, being afforded many opportunities and luxuries our father never had when he was growing up. Dad was the kind of man my brothers and I wanted to be. For Sis, it was Mom who she tried to emulate. The fact Dad had pulled himself up out of the coal mines by his football cleats, something we would never have to do, made his success story the more impressive to us.

“Dad’s the man!” was a common Robbie proclamation, a notion shared by the rest of the Slater boys.

While we were in high school, Dad drove a white Buick Skylark, complete with a broken-off driver’s side door handle. It ran pretty well, so Dad kept it. Dad knew-and so did we-that he could get a Cadillac if he wanted one and that was the point. Dad was sending a subtle message which, over the years, was not lost on us. Perhaps also it was a small act of defiance. It was far better to be able to do something and choose not to rather than do something or try to be somebody you aren’t because others expect it.

“Your Mom and I always cared more about our kids going to college than living in some big, fancy house,” Dad remarked years later.

Robbie and I were more irreverent and far more edgy than our parents. Dad’s irreverent and defiant streaks were there, but kept under restraint. Dad had too much class to be spouting off and acting dumb with the regularity of his boys. On occasion though, even Dad allowed himself to sink into silliness, offering a verbal glimpse of the genesis of this particular family trait. When referring to someone who enjoyed the obvious benefit of second, third or fourth generation wealth, Dad jokingly remarked,

“He got his company the old-fashioned way – from his father!”

“Good work if you can get it,” was Robbie’s common rejoinder.

Robbie referred to Dad as the “lender of last resort.” Dad and Robbie were both neither borrowers nor lenders, but it was a long-running family joke, dating back to a young Robbie going to Mom and Dad with requests for them to “invest” in climbing equipment or parachutes.

Dad also talked about the need to “be in the game.” To him, as a student of history and one who loves exploring ideas, life is full of fascination and opportunity. Dad hoped we would recognize this and encouraged us to search for our individual passions and niches. Doing something also entailed the responsibility of doing something productive. To Dad, the ends did not necessarily justify the means.

When we were younger, I believed only Robbie was lucky enough to have discovered a passion for something that approached Dad’s love for surgery and medicine. Rock climbing, mountaineering, ice climbing, skydiving and then BASE jumping became Robbie’s passion. Robbie was like Dad in a climbing harness instead of scrubs-with the irreverence, defiance and outspokenness traits amplified by several orders of magnitude.

The rest of us Slater boys also liked to see ourselves as some image of our father, but recognized we were merely varying, less refined versions. Dad had the polish of a true gentleman. We each carried the trait, owing to Dad and Mom, but it was something which sometimes bobbed below the surface. Our minds were adequately trained and mostly willing, but the flesh was occasionally weak. Nevertheless, Dad was always the gold standard of honed.

“Those boys just idolize their father,” Mom would say. Dad would say to us: “Remember, I’m your biggest fan,’ his most common words of encouragement and approval.

The West Virginia high school all-star football game scholarship was Dad’s ticket out of the coal mines. Contemplating his own dad’s advice, Dad chose medicine, a fascinating field where he could be independent and contribute to society. Following medical school at Maryland University, his surgical internship led Dad to Milwaukee, Wisconsin. One day in the operating room, he met a slender blonde nurse named Mary Krizek. After their first date, he said he’d call again. Playing it cool, he waited several weeks and, at the point where Mary had just about given up on him, he called back. Six months later they were husband and wife.

Mary Krizek was a hometown girl, the daughter of a prominent local family. Grandpa Chet Krizek was the long-time mayor of Shorewood, a Milwaukee suburb, a respected attorney and an accomplished sport and gamesman. Oftentimes when we were visiting, sheriff’s deputies came by the house for business related to Grandpa being mayor. They were always in uniform, complete with guns, extra ammo, handcuffs and nightsticks. We all thought that was cool.

Three walls of main family room in the Krizek home were covered with built-in bookshelves. Interspersed among the books were many trophies Grandpa won over the years for basketball, billiards and bowling. There were also many photos of a younger Chet, which included basketball team pictures, shots of him playing in billiard tournaments and photos with his bowling buddies. Grandpa Chet smoked and had slicked back hair which, in my opinion, made him look tough. My brothers and I agreed that in his day, Grandpa Chet was a bad-ass – or, as Robbie and I said, honed.

As he got older, Grandpa Krizek’s real interest was taking his grandsons fishing. Although suffering from arthritis, which caused painful swelling in his hands, he was always able to rig up poles, bait hooks and untangle the constant messes caused by four little boys. For us, fishing was a fun new way to experience a different aspect of the wild.

Grandma Betty Krizek had a charm bracelet with a little gold hearts with the names of every child and grandchild in the family. My brothers and I would gather around as she showed each one to us and told a story about that person when they were young. We liked hearing about Mom as a young girl on the swim team

At the age of 92, Grandma was incensed when Mom and her sister Betsy told her it was time to give up her driver’s license. Grandma protested vehemently as her friends, themselves well into their eighties, nineties or beyond, would be left without transportation.

“I pick them up so we can play cards and visit. Sometimes we have a couple of bourbons and when we’re all ready to go back home, I drop everyone off,” Grandma protested. No one ever got hurt and eventually Grandma Betty agreed not to drive. Grandma’s defiance and determination were pretty honed, too, Robbie and I thought.

Art Gilkey was a geologist from Iowa, finishing his Ph.D. at Columbia University when he joined the Third American Karakoram Expedition to K2 in 1953. The summer before, he had directed the Juneau Icefield Research Project in Alaska and was well-known for climbing Devil’s Tower as a boy and his numerous ascents in the Grand Tetons. During the expedition’s descent of the Abruzzi Ridge, despite being secured by two separate ice axes anchored in the slope, Gilkey, in an instant, was blown off the mountain, disappearing in a cloud of white at 25,000 feet. Before his team, badly battered by their ordeal, left on their return to civilization, they erected a 10-foot rock cairn to commemorate their fallen companion. At the base of the cairn they placed a small metal box containing some mountain flowers, the expedition flags intended for the summit, a poem and a statement about their friend. On top, they placed Art Gilkey’s ice axe. Since then, the Gilkey Memorial has accrued numerous plaques and mementoes of those lost on the “mountaineer’s mountain.”

In 1954, an Italian expedition led by Ardito Desio challenged the Abruzzi Ridge. As camps were being established, Mario Puchoz, an Alpine guide of legendary toughness and determination, developed a nagging sore throat. Not one to complain, he was not about to abandon the climb due to a slight cold. The weather then deteriorated, along with Puchoz’s condition. In the days that followed, his breathing became irregular and, in the early morning hours of June 21st, Mario Puchoz expired. Rather than call off the expedition, the climbers pressed on and, after an epic struggle for survival and the summit, Achille Compagnoni and Lino Lacedelli reached the top of K2.

Mom and Dad also told us stories about ourselves where we were little. We didn’t always remember what we’d done – and even when we did, we didn’t remember it from the perspective of our parents. We especially liked hearing stories about our supreme acts of foolishness for which, due to the passage of time, we could no longer be punished. Mom and Dad could no longer be mad and as Dad told them to us in the tent, he also thought they were funny.

One of their favorites – and ours too – happened during our year in Cleveland, when Robbie and I were six, Paul was five and Tommy three. One day, with the efficiency of a veteran fire crew, we dragged the garden hose to Mom’s 1962 Chevy convertible, which was parked on the street in front of the house. The hose was placed in the front seat and turned on. Slowly the car filled with water as we gleefully watched. When it filled up we would go swimming. No one was the wiser until the water level reached the dashboard. For mechanical reasons which were never fully explained, the car’s horn went off.

Running outside, Mom could do little more than turn off the hose. The horn, however, continued to sound, drawing the attention of the neighborhood, especially the kids. Mom had to call the fire department and then wait, as the horn blared, until they showed up. We were thrilled to see the fire engine pull up, sirens blaring and bells a-clangin’, with the firemen, decked out in their big boots, fire coats and hats, hanging off the sides of the truck. The firemen jumped off the truck and eventually got the horn to stop. Exasperated, Mom could only shake her head.

Another one Robbie and I especially liked to hear again and again happened the year prior, in New Haven, Connecticut. A new house was being constructed down the street. We liked watching the workers with their tool belts and interesting equipment. Like garbage men, the workers also had cool gloves. We had tool belts, too. One evening, Robbie and I sneaked out of the backyard and down to the construction site. Believing our assistance would be thoroughly appreciated; we pried open several paint cans and got started. As we worked, we commended ourselves for the job we were doing.

“I wonder how much they’re going to pay us!” Robbie proclaimed with a wide-eyed grin. We were not offered payment for a job well done. Instead, Dad had to write the owners a check for the damage.

“We were so mad,” Mom recalled, “but what could we do? You guys…”

A few years later a similar situation occurred when, without being asked, we helped out by harvesting all of the vegetables from a neighbor’s garden.

Curious minds and fertile imaginations, Mom believed, if lovingly cultivated, could grow to bear the fruit of great adventure and worthwhile accomplishments. This held true for kids as well as adults. Sometimes, though, our curiosity trumped our collective common sense. But Mom always thought that the more we spread our wings, the higher we’d have a chance to fly. In the meantime, Mom didn’t sweat the small stuff.

These stories not only filled the tent with laughter, but helped instill in us a sense of family identity. Our favorites always focused on our ancestors’ traits of independence, quirkiness and subtle irreverence. It caused us to embrace these attitudes. It gave me – and I know it gave Robbie – a framework which encouraged our own individuality. We may not have been necessarily special, but we were at least different.

When Robbie was older, he seemed to get a kick out of Prince Charles of England, mostly because he was married to Princess Diana, who Robbie found quite attractive. Had the prince’s mom the Queen passed or given up her title, Charles would ascend the throne as King. If Charles got his chance, Robbie wouldn’t have watched on TV as the new king rode through the streets in his gilded carriage draped in the ermine robe of regality. Robbie didn’t fault the prince for being born into a position of privilege – “Good work if you can get it” he would say, but this comment transparently masked an element of jealousy Robbie felt. Charles had been born lucky, through no effort or merit on his part. Robbie and I knew we had been born pretty lucky ourselves, also through no effort or merit on our parts. If Charles got to be king, he should at least try and be a good one. Robbie and I felt we had the same kind of obligation, albeit without a title.

This comment also masked another, though not readily apparent element of Robbie’s personality: insecurity. Would he be able to live up to Dad, much less be a great king? Though Robbie never expected anything handed to him he felt, as did I that we had to at least try and live up to the best of our legacy.

Dad always said, “In the end, the only thing you have is your integrity. What counts is the type of person you are and what you stand for. If you want to parachute off buildings or run across Antarctica, that’s beside the point.”

Or as Mom put it, “It doesn’t matter if you’re a lawyer or a doctor or a candlestick maker, as long as you’re the best one you can be.”

Or, as Dad concluded, perhaps less profoundly, “I don’t care what you do – just do something.” Whatever that “something” was, however, we would have to figure out for ourselves.

As part of a lineage of characters with the courage of Grandpaps Hannah, adventurousness of Grandpa Slater, cool confidence of Grandpa Krizek, good-natured defiance of Grandma Krizek, subtle irreverence of Grandma Slater and the determination and self-reliance of Dad, as Robbie got older he felt not only compelled but entirely justified not just in doing something but in carrying that something one step further than anyone else. This was especially true when he was in the mountains, surrounded by the spirits of the wild.

Robbie knew he wouldn’t be a king, but he also knew he could – and should – seek to become the king of whatever something he chose to do.

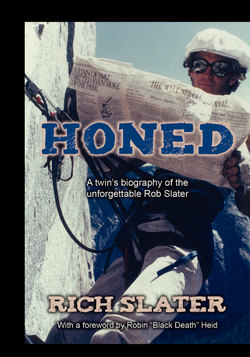

With Grandpa Chet (Robbie on left)