Читать книгу Honed - Rich Slater - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter II

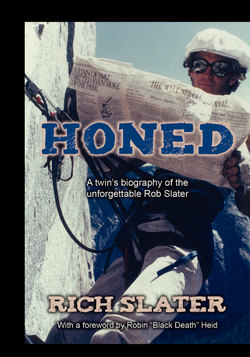

ОглавлениеRobbie on casual belay

“Only those are fit to live who do not fear to die; and none are fit to die who have shrunk from the joy of life and the duty of life. Both life and death are parts of the same Great Adventure.” -Theodore Roosevelt

No one is sure who first “discovered” K2, for no written history is kept by the Balti herdsmen who inhabit the Karakoram Range between China and Pakistan. They rely on memory and lore to pass knowledge along to succeeding generations and live today as they always have, in a world detached by time and space from the creature comforts of modern civilization. In fact, debate remains surrounding the issue of what, if any, native name exists for the peak now known as K2. My twin brother always subscribed to the school of thought accepting Chogori, meaning “Great Mountain,” though to him it was his Dream Mountain.

It was the first week in August, 1973. Robbie and I were 12. We stood at the base of the cliff, ready to begin our first climb. A series of cracks, broken into pitches by intermittent ledges, ran up the wall of Cascade Canyon flanking the Grand Teton in Jackson, Wyoming, where they met the sky. As Robbie surveyed the route above, his eyes tightened. I could see the picture he had of himself on the rope, high on the wall, higher than we had ever climbed with the clothesline on the rock formations of Vedauwoo outside our Cheyenne home. I had the picture too.

It was clear from the start that some of our fellow students of the Exum climbing school would never come to grips with the height and exposure of clinging to these massive cliffs. They were just tourists and rightfully scared, but Robbie and I were not, for even at our young age, mountain cliffs and rock faces were not new to us. During our many weekends clambering about the Vedauwoo rocks, we had climbed everything we could, in our cowboy boots and often with the aid of a clothesline. We had sat on many ledges peering into space and looked down from the edge of many precipices. We both loved heights. For us, this was a natural progression-the next step.

The instructor led the way, placing a series of small aluminum blocks called “chocks” into the crack. The chocks were attached to a loop of nylon strap onto which a carabiner, an aluminum device which resembled a large safety pin, was clipped. The rope ran easily through the “biners,” and if he slipped, the rope would be held taut from below, causing the top chock to catch his fall. This was called protection, or “pro.”

At top of the first pitch the instructor anchored himself and set up the belay. The belayer reels in the rope as his climbing partner ascends. If the climber below falls, the rope, which is pulled up around the belayer’s back, is immediately drawn across the belayer’s waist. Friction prevents the rope from paying out and holds the climber below. There was clearly a special responsibility and mutual trust inherent in the relationship between a climber and his belay. If they’re not like brothers they’re at least a team.

Robbie’s turn came and he started up. He was finally on the rope doing some real climbing. As the instructor offered praise and encouragement, I knew Robbie was just humoring him. It was way too easy. Robbie quickly worked his way up, pausing to remove the chocks and clip the ‘biners to the rope around his waist. He moved like a cat, surefooted and in perfect balance on the rock. I followed, also finding it pretty easy, disappointed I didn’t get to remove the pro and clip it to my waist. As we sat on the belay ledge waiting for the others, I saw Robbie’s eyes dilate staring up at the magnificence of the Grand Teton range, above the massive cliffs to the far-off summits in the sky. A wide, determined grin spread across his face, giving a glimpse of a razor-sharp focus which belied his tender age and which I had never before seen.

The blueness above the peaks boiled, almost imperceptively, like an immense, infinite cauldron forming an overarching canopy above us. I could see his nostrils flare and mouth quiver slightly in an unconscious attempt to smell and taste the icy winds blasting across the highest ridges and hear their distant roar. I sensed in his grin a feeling of total isolation and complete security. I also sensed his recognition of a subtle yet pervasive force. I felt it too. It was the spirit of the wild places. It was a powerful combination of inspiration and reverence. We were in the midst of the mountain gods. It caused a change to come over us both, but it would play itself out differently for each of us in the years to come. Momentarily, our eyes met. Nothing was said, but I knew he knew.

K2 was revealed to the outside world as a result of the Great Trigonometric Survey of India in 1856, an ambitious plan to accurately map all British possessions on the Indian subcontinent. From a vantage point 140 miles away, Captain T.G. Montgomery spotted a group of high peaks which he measured and logged in his survey book as K1, K2, K3, and so forth, for Karakoram Range.The other peaks were originally named K1, K3, K4 and K5, but, intent upon using native names, were eventually renamed Masherbrum, Broad Peak, Gasherbrum II andGasherbrum I, respectively. While the superintendant of the survey, Sir George Everest, had the world’s highest peak named after him, no consensus was reached for the second highest and, consequently, no official name was ever approved so it simply retained its designation as K2.

It was not until 31 years later that the great mountain fully revealed itself, at least to Westerners, when Colonel Francis Younghusband crossed the Old Mustagh Pass and the towering pyramid came completely into view.

“It seemed to emerge like a perfect cone, incredibly high,” the Colonel wrote. “I was astounded.”

In many ways, Robbie and I were like any other brothers our age. Whenever one of us tried something new, the other always wanted to follow. Our brother Paul was one year behind us and Tommy, the youngest, two years behind Paul. Inevitably, we ended up trying just about everything. For the usual stuff like football, baseball and basketball, we formed into teams. I was usually with Tommy, because I was oldest and he was youngest. It wasn’t enough just to play-we always had to organize it into some kind of tournament, Super Bowl or World Series. We played to win, mostly for short-term bragging rights, but the victory celebrations were never enough to create grudges or prevent a rematch. We also ended up pushing each other into far less traditional-and dangerous- endeavors such as bike jumping ala Evel Knievel and, later, cliff jumping. Sibling rivalry and competition among the Slater boys always led to the envelope being pushed. In many ways this competition was stronger than peer pressure. It meant more to outdo or impress a brother than it did an outsider. It was usually harder, too. This was especially true for Robbie and me.

Like all brothers, we occasionally fought. Sometimes the combat was with fists, but mostly just bickering words. One time when we were preschool age, Robbie and I got into a fight in our backyard sandbox over possession of an old army shovel, the kind used by soldiers to dig fox holes. As we wrestled for the shovel, I accidently smacked my twin brother in the head with it, which required a couple of stitches to close. For years afterwards, when we got into it, I would joke: “I’ll kick your ass just like I did in the sandbox.” Robbie would always reply, “Yeah, but you had to use a shovel, you pussy.” But that day in the Tetons, unspoken, we were together. That day there was no conflict.

We had been to the Tetons before. We were a “normal” family in many respects, but we were also lucky in the sense we not only had each other but parents, Dad in particular, who always made time to do things with his boys. Dad had a medical meeting at the Jackson Lake Lodge each summer and he brought the family. Full family participation in everything eventually gave way to each of us pursuing a more narrow range of activities, but throughout our childhoods there were some things we all liked and continued to do together such as camping, skiing and hiking.

There were many hikes and our own versions of mountaineering expeditions. This summer, Dad had stopped by the famous Teton Climbers’ Ranch, home of the Exum climbing school, located at the base of the Grand Teton. Informed the minimum age for participation was 16, Dad simply asked if he could bring his sons anyway. Asked, almost rhetorically, who would be responsible for the boys, Dad replied, “I will, of course.” With that, Robbie, Paul and I were allowed to enroll. For Paul and me it was something definitely cool. After all, not many kids got to climb with ropes and real climbing equipment-in the Tetons, no less. Dad hadn’t wanted to make a big deal of it; he just thought it would be fun. Dad never dreamed it would lead to a lifelong obsession for one of his sons. From the start, however, it was something more than fun with Robbie.

That morning, there was a slight yet recognizable bite in the air. Looking back, it was a subtle reminder of who is in control any time you go to the mountains. Racing across the Jenny Lake boat dock and beating his brothers to the best seat on the 25-foot launch made Robbie smirk with satisfaction. Being able to attend the famous climbing school, though technically four years too young to enroll, was a kind of unspoken recognition of his yet unproven abilities. But more than anything, I somehow knew the awesome grandeur of where we were made Robbie feel so incredibly alive and, for some reason, indestructible.

After a couple of multiple-pitch climbs, it was time for lunch. The baloney and lettuce sandwiches slathered in mayonnaise fell far short of our expectations. Robbie examined his with a look of incredulous disappointment but said nothing. We agreed something as cool as climbing warranted decent food to go with it.

Following lunch, the focus of the class shifted. “Making the top is one thing, but getting off and making it home is what ultimately counts,” began the instructor. There was a previously absent edge to his voice. It was kind of like the change that occurred in Dad’s voice when he talked to us about something important – like “values,” as he called them. Of course coming back down is important, but it also seemed to be the fun and easy part. I noticed Robbie’s eyes immediately focus up the canyon to where we would make the big free rappel. But the edge in the instructor’s voice made us both look at Dad, whose slightly squinted eyes and pursed lips demonstrated he knew the importance of these words – and that he wanted to make sure we did too. They would become prophetic.

The afternoon agenda consisted of rappelling, which, in its finest form, allows a climber to literally fly down the face of the rock. Robbie wanted to go straight to the 60-foot free rappel over a large overhang that he’d watched all morning. I’d noticed as he sat on the belay ledges, watching intently as the “advanced” class members, one by one, inched to the edge of the precipe, most with great trepidation, hesitant to lean back and launch themselves into space. Disappointingly, we were led to the top of a rather gentle friction pitch just slightly steeper than something we would feel comfortable down climbing unprotected. It certainly wasn’t steep enough to bounce off of the rock in long smooth arcs like we’d seen on television. No harnesses were used – just the rope snaked between the legs, across the chest, over the right shoulder and down to the left hand, which controlled movement down the rock. Given the rope’s serpentine path around the body, it was impossible to descend with any speed, much less bounce off the wall and catch some air. But it’s a safe and efficient way to descend a tricky section – and a valuable tool when trying to get off a mountain during a late afternoon storm so common in the high country.

Our group gathered on the ledge above the wall. Rigged up, one by one we backed to the edge. “Just lean back, nice and easy,” the instructor encouraged, “let the rope slide - let friction do the work.”

This was easier said than done as the natural inclination was to keep a death grip on the rope. Nevertheless, it didn’t take Robbie long to make it look easy. For all the other students, it was a question of facing and overcoming fear. For Robbie and me, the question was more like “who’s going to go for it more?” We obviously felt no need to gingerly approach the edge. Height and exposure caused no concern. We both loved it.

Several summers earlier, when Robbie and I were about eight, we went to West Virginia to visit Grandma and Grandpa Slater. Dad took us to a place called Oglebay Park that had a huge pool with three diving boards. The first two were similar to many we had seen before. The “low board,” as we called it, was a standard one-meter board, about three feet above the pool deck. The “high board” was a three-meter board, or about ten feet tall. Towering above was a third board, at least twice the height of the three-meter. The diving board itself was sawed off a couple of feet past the hand railing. It was obviously cut short to keep people from bouncing-which apparently was considered too dangerous from that height. People were jumping off- all older guys. We asked Dad if we could jump off and he said “sure.” We went right up-neither one of us was ever afraid of heights. Afterwards, Robbie and I agreed it would have been cool if the whole board was there and we could have bounced even higher.

After our climbing day in the Tetons, Paul and I proudly recounted the accomplishments of the day over pizza, but Robbie payed little mind. He was engaged in the conversation but his focus was elsewhere. I’d been basically satisfied, even though I’d expected a bit more of a challenge. Robbie, on the other hand, was convinced that the climbs were too easy, the rappels not steep enough, and everything was too low. He was fixated on ever greater heights and difficulty. The highlight of the course would be the next day’s free rappel off the big overhanging cliff, but I could tell Robbie was looking beyond. Robbie was already talking about summits and putting the skills we had been introduced to into serious application.

As I sat there next to him, it reminded me of something that happened when Robbie and I were in fourth grade. The next door neighbors got a trampoline. My brothers and I lined up to take our turns but, after a couple of times bouncing, Robbie grew bored of waiting and went back to our house. A short time later he returned and declared it would be far more exciting, rather than standing around waiting to jump on the tramp, to jump off the roof. We immediately followed Robbie back to our house, the group’s collective interest in the tramp overshadowed, at least temporarily, by the anticipation of perhaps witnessing a leg being broken. From the fence, Robbie climbed to the roof and appeared above us. He inched to the edge, as the crowd below loudly admonished him that holding onto the gutters would somehow constitute “cheating.” Robbie jumped, hit the ground with a thump and rolled on the grass as we watched in disbelief. I went up and jumped off as well, though the real admiration rightly belonged to my twin who went first and, in so doing, inspired others to follow. In this case it was just me, but as time went on he inspired many others as well. Robbie was not content with the trampoline and, more specifically, with waiting in line to do something every other kid in the neighborhood could do. I followed, but Robbie led the way.

During that year of fourth grade, we lived in Salt lake City, Utah. Our house was in a new development built at the base of the mountains flanking the western edge of the city. We were on the last street, so our yard literally backed up into the mountains. My brothers and I spent hours, regardless of the weather, hiking, playing and exploring. We had forts, racetracks for our bikes and our own ski runs. Nearby was a large outcropping of granite near the top of steep slope. On it was painted a large “H” for Highland, the local high school. We were warned by the neighborhood kids about exploring it as high school kids patrolled it to keep non-students away. We ended up going anyway, of course. From its base, the huge black vertical sides of the H rose above us. There was so much paint poured on the rocks it looked like it had been covered with smooth black lava. Looking around, we were the only ones there-no patrolling high school kids.

“I’m gonna climb it,” Robbie stated, and started up. As usual, I followed.

The next morning at the Exum school, we again separated into small groups, each with an instructor. As the group left the staging area near the boat dock, Robbie led the hike up the trail to the cliffs. At first I entertained thoughts of passing him, but ended up having to settle for being in front of everyone but him. Over the years, I would spend many miles behind Robbie on the hikes, trying to match him step-for-step along rocky mountain trails. I usually did a pretty good job, though always from behind.

Once we arrived at our climbing area, we found that the climbs were more challenging and we got to use more of the equipment. For Paul, it was quite satisfying, though in keeping with his personality, he didn’t say much. For me, it was a great, exhilarating experience. I was happy to have had done it and, for that matter, to able to now say I had.

“This is so cool,” I said to my twin, who nodded in agreement as his face lit up with his big grin, but at the top of each pitch, it was apparent to me that Robbie’s appetite for a steeper, more challenging route remained unsatisfied. In fact, he was hungrier for it now than he had been when we started the class. For him, there just seemed to be no better combination than height, exposure and difficulty. I didn’t know the word at the time, but right in front of my eyes Robbie had become insatiable in his desire to climb.

At long last, it was Robbie’s turn for the free rappel. As he roped up, I couldn’t help but notice the shine on his face, outlined by his thick mop of hair. We all grew it the same way and had it as long and wild as Mom and Dad would let us. In contrast the students who had gone before, Robbie backed towards the ledge with a single-minded purposefulness which demonstrated a total absence of fear. I think everyone watching, including the instructors, was impressed. Grudgingly, perhaps, I was too.

“Be sure and lean back, especially at the edge,” the instructor counseled as he has done with all the students.

At the end of the precipice, Robbie felt the knife edge of the ledge under his arches as he bent his knees, pressing on the rock in a challenge of strength. Leaning back, slowly allowing the rope to slide through the ‘biner, Robbie knew his next step would be his last before reaching the ground some 60 feet below. Coiling like a rattlesnake, he launched himself backwards and opened his right arm, freeing the rope of friction. For a fleeting instant, the sky’s vault opened. Robbie glimpsed the heavens, then only rock. I saw his face, joyfully intense and happy, before he disappeared below. This time I was definitely impressed. Robbie’s first arc didn’t stop until about 20 feet below the ledge. No one else had flown nearly that far. He felt the give in the rope as he bounced and swung, slowly beginning to spin.

Robbie did not want to stop but, unfortunately for him, he was obligated to land. Opening his arm, Robbie slid down the rope, periodically checking his speed, stopping to enjoy the bouncing, swaying and twirling caused by the interruption of his downward flight. For Robbie, being airborne was clearly an unrivaled sensation. Upon landing, like the others before him, he was greeted with a congratulatory cheer.

“I want to do it again.” Robbie was dead serious – especially for a 12-year-old. Part of him may have just wanted to show the group that he really wasn’t afraid to do it again. Just about everyone had expressed at least a feigned desire to go back up, but most probably found the experience terrifying and were, in truth, glad it was over. I would have done it again but didn’t press the issue, but Robbie truly wanted to go back up. I think it had more to do with him wanting to prove something to himself and push himself further rather than showing off for or trying to impress anyone else. There was a palpable difference between the way Robbie reacted compared to me and the rest of the students. Standing there watching, Salt Lake City flashed through my mind — when he jumped off the roof in fourth grade, or led the assault on the “H.” As he did then, Robbie had again separated himself from the pack.

Rockefeller Memorial Parkway runs parallel to the Teton Range through Moose Flats and skirts the Jackson Lake Dam before turning east to Moran Junction. As our station wagon was loaded, we claimed our seats for the first leg of the journey home. Robbie made sure he got the window seat in the back, behind Dad, which provided him the best and longest-lasting unobstructed view of the Tetons.

It was always awe-inspiring looking at the Tetons; they’re not the most photographed mountains in the world for nothing. I saw him wondering how its cliffs compared to those he had just conquered with so little difficulty. In my mind’s eye, I could see Robbie on the highest summit, at the edge of the cauldron, dreaming of diving in, or up. I knew he would be back and that, someday, he would stand on the top of every one of the Teton summits and get the chance to fly.

But Robbie was doing more than just enjoying a spectacular natural view. With face close to the glass, he studied the peaks, the Grand Teton in particular. They seemed so far away and he was clearly sad to be leaving. Robbie gazed longingly and knowingly at his newfound love as if he had realized and was now set to develop a relationship he knew would get serious. There was also the component of risk, excitement and adrenaline that came with the courting. He had felt it when he was on a particularly steep or difficult section of a route. He felt it when he had gone to the edge of the ledge on the big free rappel. Robbie discovered an important part of himself those two summer days in 1972. It was an arrival for him but also marked a departure. I wanted to follow, but I was unsure how far…

Robbie, left, Paul and Richie

Rob, Paul, Tom, Sis and Rich