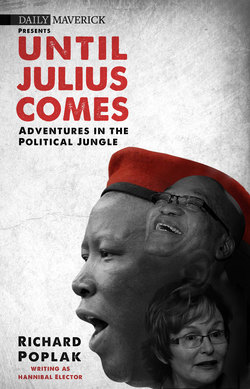

Читать книгу Until Julius Comes - Richard Poplak - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

12 FEBRUARY 2014, JOHANNESBURG CBD

ОглавлениеIn which the Democratic Alliance marches to Luthuli House, to present a demand, wrapped inside a proposal, for 6 million ‘real jobs’.

‘In modern Athens,’ the philosopher Michel de Certeau once noted, ‘the vehicles of mass transportation are called metaphorai. To go to work or to come home, one takes a “metaphor”.’

One week after the ANC’s non-march, anti-rally rally, Johannesburg was, as usual, jammed with metaphors – in this case, the buses that brought in DA supporters and ANC supporters, who gathered on either side of the central business district.

‘Viva Helen Zille viva,’ yelled one half of the city. ‘Viva President Zuma viva,’ yelled the other.

The meaning of the humming metaphors that lined Miriam Makeba was easy to decipher: in a divided city, which was built to maintain divisions, the buses were intended to make those divisions plain. The DA, led by Helen Zille, were here to deliver a jobs proposal to the ANC, who were encamped to protect the integrity of the revolutionary house from those who hoped to defile its honour.

Before the first Molotov cocktail had been thrown, before the first rubber bullet had been fired, I stood outside Luthuli House and spoke with a Department of Community and Safety spokesperson named Obed T.I. Sibasi. He assured me that the morning would unfold without trouble. We were alongside in a circle of dancing ANC supporters, and Sibasi was explaining how it was his department’s responsibility to protect citizens, not encourage their shitty behaviour.

‘That is why we will ensure that the DA will avoid this area’ – he was pointing to Luthuli House’s entrance – ‘for the sake of the peace. That is why we say there will be no problems.’

It was difficult to know whether Sibasi and I inhabited the same reality because, from my vantage point, problems looked both imminent and certain. The ANC contingent, now a couple of thousand strong, were armed with struggle songs, cattle crops, sticks, bricks, bats, flags, freezies, berets and T-shirts. They were, to my eyes, a fully operational street army. To Sibasi, however, they represented a slight traffic headache.

‘Will the DA make it to Luthuli House to deliver their jobs thing?’ I asked.

‘We are not sure of the outcome,’ Sibasi told me. ‘But that is not our business. We are concerned with public safety.’

With that in mind, I strolled along Marshall Street towards the DA encampment, which had been set up at the Westgate Transport Hub at Miriam Makeba and Anderson. A city sliced in half – yellow and green hither, blue and white thon. Getting my white ass into the DA assembly area was no easy task – first, I was frisked by an enormous nightclub bouncer wearing a black dinner jacket, dark jeans and a neon safety vest, and then I was frisked by another. The DA’s security contingent seemed recruited from nearby nightclubs, their expertise better suited to selling cocaine and punching drunk people in the face than managing a political rally.

Inside, the DA supporters were armed with T-shirts, berets, white-dude ponytails, fat hippies, flags, and signs that read ‘6 million REAL jobs now’. The DA’s Gauteng leader, John Moodey, dressed like a Sylvester Stallone character in a black beret, aviator shades and a flak jacket, warned those who had brought children to stay behind. ‘We will have no children on the march,’ he said. ‘We’re marching for their future.’ Dead babies, after all, make for bad television.

As the bouncers wrangled the crowd, Mmusi Maimane – the DA’s candidate for Gauteng premier – swept in wearing overalls and a hard hat, all set to build democracy. (He would shortly have a number of bricks at his disposal in order to do so.) The media was asked to gather outside under the shade of a tree, and await Madame Zille, who would address us before leading the march.

When she showed up, Zille was resolute. Nothing, she explained to us, would stop the DA from executing its constitutional right to march through the city to deliver an inchoate jobs proposal to the baffled concierge in the ANC’s Bat Cave.

‘We will march for 6 million real jobs,’ she insisted, ‘and not the bogus jobs that the ANC are offering.’ She said that the metaphors the ANC supporters rode in on were ‘state funded’, and although the ANC army were carrying caveman weapons like branches and stones, the police had yet to do anything to quell their thirst for blood. ‘We’re protecting the right for everybody in the country,’ she said, to deliver paperwork to the ANC.

With that, she donned a hard hat and walked into the crowd, who now doubled their efforts regarding song and ululations. Zille looked suitably working-person-like, except for the fact that her dangling earrings did not seem regulation, and would probably get caught in machinery were she an actual blue-collar wage slave. The DA party bus jerked unhappily into motion, to cheers from those in the mining headquarters that lined the route to Luthuli House.

And Johannesburg did feel like its essential self – a dusty sunbaked mining town, full of people bused in to work or fight or fleece the joint, and then get the hell out as soon as darkness fell. The bouncers, who owned the Joburg night, kept a tight cordon around the marchers, with an armoured vehicle and a bakkie (belonging to the ominously named South African Police Services’ ‘Saturation Unit’) taking the lead. All was well, until the proceedings jammed up on the corner of Rissik Street.

In the service of foreshadowing, I asked John Moodey if he was expecting trouble. ‘We always expect trouble,’ he told me, ‘and that’s why we take these extraordinary protections of the marshals.’

I’m not sure what Michel de Certeau has said, if anything, about the art of the ambush, but it is always most beautifully executed in the planned grid of a city. The ANC contingent was now rounding upon the DA marchers. The cops quickly formed a cordon, and when the stones and bricks were hurled at our unprotected heads, the police threw a series of stun grenades, pushing the crowd back.

The ANC supporters ran towards Miriam Makeba, trying to dog the DA march, which had now turned back because, um, obviously. As the cops formed a tight line, cocking their shotguns, a petrol bomb performed a slow, sultry arc, exploding on the tarmac in a streak of fire. Another whirled in, which was met in turn with four rubber-bullet blasts, and another stun-grenade fusillade. Two student journalists, wearing hip-hugging hipster shorts and brandishing iPhones, giggled with excitement. ‘Dude!’ said one, ‘this is all just so amazing.’

And so this insane, pointless spectacle descended into the familiar narrative of white cops chasing wily, be-T-shirted ‘revolutionaries’ down alleyways and streets, guns cocked, grenades popping. It was an artful rendering of days of olde, when Johannesburg was alive with such violence. Except, this time, there was nothing to fight for, and nothing at stake but a fake jobs proposal intersecting with a government already accomplished at creating fake jobs. It was the meaningless jibber-jabber of party politics etched onto the city’s streets, leaving them strewn with the residue of a battle forged by PR hacks.

When it all died down, I spoke with the ANC’s Deputy Secretary, Jessie Duarte, inside the air-conditioned foyer of Luthuli House. She looked small and red-eyed and wiped out by the heat. ‘When you provoke the ANC in the manner that they did,’ she said to me, ‘people respond. This was the march of people claiming a portion of the ANC’s manifesto.’

But what of the fact that the ANC’s contribution to the day’s proceedings was illegal, considering the fact that they did not have the right to gather, and that their members were tossing bombs?

‘I think it’s shameful what the DA did. People came to protect us! And when they come, we can’t turn them away. The DA came with batons and helmets and shields. That is provocation! In the history of South African marches, we’ve never been in the position we’ve been in today.’

Duarte was, of course, stating an untruth regarding the DA’s level of belligerence – armed struggle is not in the party’s DNA, and I’m not sure their mumu-wearing numbers would know how to so much as light a Molotov cocktail. But bullshit is one of Duarte’s mainstays, and she looked so tired and old that I left her to it.

I walked away from the dancing and chanting, and made my way down Sauer. The city was relaxing, reforming. The DA metaphors were now driving in convoy out of the CBD, and a group of ANC supporters were throwing rubbish from the sidewalk at the departing blue shirts. A large woman with braided hair walked alongside the buses, slamming an empty two-litre plastic bottle of Iron Brew against trees and lamp posts, each ‘bang’ sounding like the rapport of gunfire.

Then, a man raised a brick and aimed it at the fleeing buses. But the cops ran up to him and chased him away into the dust and heat of the useless day.

This is our political discourse. This is what we’ve done with democracy. Twenty years into this journey, and all we insist on creating is metaphors for the past.