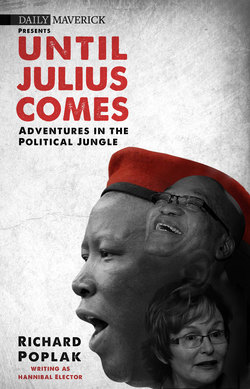

Читать книгу Until Julius Comes - Richard Poplak - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеGEFÜHLSLEBEN

AN INTRODUCTION

This is a book about madness.

Every word is made up – the words themselves are coined specifically for this undertaking. The incidents detailed herein did not happen; the world in which the essays are set does not exist. There are, of course, moments of clarity to be found within these pages, but they only serve to highlight just how compromised this volume’s version of truth happens to be. A slight correction: this is a work not about, but of madness.

Which is to say it’s a book about South African politics.

Specifically, the book details the 2014 general-election campaign, the fifth such endeavour in South African history. The elections announced the 20-year anniversary of the country’s democratic era, and it’s worth asking – what’s changed since the non-democratic era? Answer: everything. And nothing. South African politics exists in the gulf between those two contradictory positions, exerting its tidal pull on the South African psyche, yanking us from any moorings to sanity we might have had were we not long ago admitted to history’s loony bin.

‘Everything begins in mystery and ends in politics,’ said French essayist Charles Péguy. But imagine a country in which the reverse is true. When real human subjects start practising it, when we tamper with the machinery and soil it with hamburger grease and halitosis, politics becomes highly specific – an indigenous art with its own native contours. In some countries, politics is an outgrowth of the state’s foundational virtues, however imperfectly expressed. Others practise the politics of veneration – of a monarch, of an autocrat, of an Idea. And others see politics as a means of getting things done, as the fuel for bureaucracy’s two-stroke motor.

In South Africa, we practise the politics of obfuscation. Our politicians are verbicidal – they slaughter sense, they murder meaning. Their intention has always been to hide the true reason for the state’s existence, which is to plunge mineshafts into the earth’s crust, and hose cash and commodities directly into the London Stock Exchange. In their countless acts of dissembling, our leaders have for centuries woven worlds, concepts and realities out of the vapours rising from their own bullshit. Theirs are utopian projects: the British civilisers; die Boerevolk; the Rainbow democrats. And so, stories compete, clash, erase each other, until someone mixes a Molotov cocktail and sends it arcing majestically into the night.

The German philosopher Hegel believed that madness had therapeutic qualities. Going crazy, he noted, was an effort to heal the ‘wounds of the spirit’, a means of regressing to a moment before the psyche was irrepressibly damaged by the lousiness of being alive. He described the place the mind retreated to in such times as ‘the life of feeling’ – the big, blousy German word is Gefühlsleben. Here, the language of wakefulness is replaced by an archaic language that describes dreams and fantasies, a phenomenon Hegel explained as ‘sinking back’, a separation of the mind from ‘contact with actuality’. Madness wasn’t an aberration or a chemical imbalance, but a necessary reaction to trauma.

South Africans are mad because we’ve been driven mad. When a country’s rulers rule not by leading, but by faking reality, the cheapest way for them to do so is to employ the grammar of the asylum. South Africa’s actual actuality, the one we are constantly encouraged to sink back from, is a very, very bad place, lovely scenery and good beef notwithstanding. The endlessly clanging mineshafts clang their way through the day and night, without respite.

It’s enough to drive you nuts.

Some context: I wrote everything collected in this volume very quickly. I wrote late at night and early in the morning. I often pressed ‘send’ in a hypnagogic fog, barely registering the whistle of a file tearing off into cyberspace before I passed out wearing stained track pants. I wrote in a sort of fever, lashed to history’s mast while one of democracy’s frequent shit storms raged around me.

Indeed, as anyone who has covered one will tell you, an election is the collective human project that most resembles a meteorological disaster. The observer can never anticipate in what direction the winds will blow next, whether hail will come down in spinning fist-sized knuckle balls, or whether the sun will break through the clouds and allow for a few moments of reflection. The sun, of course, never breaks through the clouds, and there is never any time for reflection.

You write to counter the spin, and they spin to counter the writing.

All of these pieces were posted to the news site Daily Maverick within hours, in some cases minutes, after they had been written. Has the news ever been in such a rush? As far as this book is concerned ‘new media’ has been reverse-engineered into ‘old media’, because the idea behind these essays, composed under the nom de plume Hannibal Elector, was to write the election, to offer stories as antidotes to the stories we were being sold.

There is, of course, a long tradition of literary non-fiction in this country. There is much solid investigative reportage and daring 140-character on-the-ground commentary. But there is also lots of crappy journalism, some of which falls suspiciously in line with the narrative that our leaders are peddling. The source of South African insanity is, and always has been, the power of Power’s narrative. With respect to Hegel, Hannibal Elector – a fake name referencing a fictional serial killer – seemed like the best way to stave off the madness, at least for a moment or two.

This is not a systematic breakdown of the 2014 election campaign. This is not a meticulous analysis of strategy or policy. It is a collection of moments, a bearing of witness. There was no planning, unless you consider having no plan a plan. The pieces have been edited only for clarity; their roughness and urgency is the whole point. They are all about madness, about unreality. They are a doormat in a doorway inscribed with the message:

Welcome to the Gefühlsleben.